Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - New Bern, North Carolina

Overview >> North Carolina >> New Bern

New Bern: Historical Overview

|

New Bern, North Carolina, may be most famous for being the town in which Pepsi-Cola was invented. Yet its history started long before 1898, the year pharmacist Caleb Bradham started selling his new soft drink. The area was first settled in 1710 by Swiss and German immigrants. Led by the Baron Christoph von Graffenried, Franz Louis Michel, and John Lawson, the community was named after the capital of Switzerland. New Bern was the first permanent seat of the colonial government of North Carolina and became the first state capital after the American Revolution.

|

Stories of the Jewish Community in New Bern

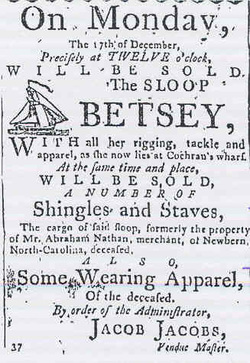

Ad selling the Betsey's cargo after Nathan's death

Ad selling the Betsey's cargo after Nathan's death

Early Jewish Settlers

The first evidence of a Jewish presence in New Bern comes from a tragic incident of mutiny on the high seas. In October of 1787, Abraham Nathan, a Jewish resident of New Bern, was traveling to Charleston, South Carolina, on his boat, Betsy. The ship’s master, William Rogers, and four crewmen, John Masters, Richard Cain, Richard Williams, and William Pendergrass, conspired to kill Nathan and take his trunk, which was filled with $500 in French crowns and Spanish dollars. According to William Pendergrass’ confession, Rogers came up behind Nathan and struck him in the head with a sassafras root, and, after Nathan fell to the ground, the ship’s master hit him twice more. Nathan did not die at that point, but clearly was not going to last much longer. William Rogers tied a large iron pot to Nathan’s wrist and threw him overboard. Rogers and Masters then went into Nathan’s trunk, took the money for themselves, and gave Pendergrass a portion to keep him quiet. Not long after, Pendergrass confessed to what had happened and all five men were arrested and eventually hanged.

Just two years after this incident, Rabbi Jacob Abroo, who was traveling the world to raise money for yeshiva schools in Palestine, came to New Bern and died. His obituary was published in the North Carolina Gazette and he was buried in a city cemetery that no longer exists. His presence in New Bern indicates that there were likely Jews living in the coastal town in 1789.

Though the Jewish presence in New Bern was small, certain people made lasting impressions on the larger community. In 1808, Jacob Henry, who was a resident of nearby Beaufort and a member of New Bern’s Masonic Lodge, was elected to the North Carolina House of Commons, becoming the state’s first Jewish legislator. The following year, he was challenged by another legislator, who claimed Henry should not be seated because “he denies the divine authority of the New Testament,” which disqualified him from holding “civil” office, according to 1776 North Carolina Constitution. In response to this challenge, Henry delivered an impassioned speech defending religious liberty in America. The speech was later published newspapers and oratory collections, and a number of historians have credited Henry’s oratory with moving the legislature to dismiss the challenge. More recent analysis, however, suggests that a technical legal argument actually convinced the legislature allowed Henry to take his seat.

New Bern Jews had to face other obstacles, including laws against operating businesses on Sunday, the Christian Sabbath. In 1822, some non-Jews in the town maligned the character of the brothers E. and M. Abrahams for doing business on Sundays, contrary to the “blue laws” that were in place at the time. An anonymous correspondent called “Atticus” wrote to the Carolina Sentinel, pleading for religious toleration and arguing against the blue laws. Despite this conflict, the Abrahams remained in New Bern, owning an establishment called the “Economy Store.” Nevertheless, they still attracted controversy. In 1844, in response to negative rumors about their character and integrity, they wrote to the Newbernian newspaper denouncing these charges and threatened to bring charges against those who spread them. They concluded, “our intention is to continue here in the same business, and not to be driven off by a herd –matters not how jealous they may be.”

The first evidence of a Jewish presence in New Bern comes from a tragic incident of mutiny on the high seas. In October of 1787, Abraham Nathan, a Jewish resident of New Bern, was traveling to Charleston, South Carolina, on his boat, Betsy. The ship’s master, William Rogers, and four crewmen, John Masters, Richard Cain, Richard Williams, and William Pendergrass, conspired to kill Nathan and take his trunk, which was filled with $500 in French crowns and Spanish dollars. According to William Pendergrass’ confession, Rogers came up behind Nathan and struck him in the head with a sassafras root, and, after Nathan fell to the ground, the ship’s master hit him twice more. Nathan did not die at that point, but clearly was not going to last much longer. William Rogers tied a large iron pot to Nathan’s wrist and threw him overboard. Rogers and Masters then went into Nathan’s trunk, took the money for themselves, and gave Pendergrass a portion to keep him quiet. Not long after, Pendergrass confessed to what had happened and all five men were arrested and eventually hanged.

Just two years after this incident, Rabbi Jacob Abroo, who was traveling the world to raise money for yeshiva schools in Palestine, came to New Bern and died. His obituary was published in the North Carolina Gazette and he was buried in a city cemetery that no longer exists. His presence in New Bern indicates that there were likely Jews living in the coastal town in 1789.

Though the Jewish presence in New Bern was small, certain people made lasting impressions on the larger community. In 1808, Jacob Henry, who was a resident of nearby Beaufort and a member of New Bern’s Masonic Lodge, was elected to the North Carolina House of Commons, becoming the state’s first Jewish legislator. The following year, he was challenged by another legislator, who claimed Henry should not be seated because “he denies the divine authority of the New Testament,” which disqualified him from holding “civil” office, according to 1776 North Carolina Constitution. In response to this challenge, Henry delivered an impassioned speech defending religious liberty in America. The speech was later published newspapers and oratory collections, and a number of historians have credited Henry’s oratory with moving the legislature to dismiss the challenge. More recent analysis, however, suggests that a technical legal argument actually convinced the legislature allowed Henry to take his seat.

New Bern Jews had to face other obstacles, including laws against operating businesses on Sunday, the Christian Sabbath. In 1822, some non-Jews in the town maligned the character of the brothers E. and M. Abrahams for doing business on Sundays, contrary to the “blue laws” that were in place at the time. An anonymous correspondent called “Atticus” wrote to the Carolina Sentinel, pleading for religious toleration and arguing against the blue laws. Despite this conflict, the Abrahams remained in New Bern, owning an establishment called the “Economy Store.” Nevertheless, they still attracted controversy. In 1844, in response to negative rumors about their character and integrity, they wrote to the Newbernian newspaper denouncing these charges and threatened to bring charges against those who spread them. They concluded, “our intention is to continue here in the same business, and not to be driven off by a herd –matters not how jealous they may be.”

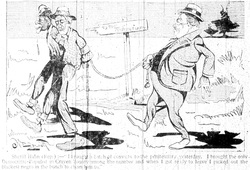

Political cartoon depicting Meyer Hahn on the right

Political cartoon depicting Meyer Hahn on the right

A Small Community

In the year 1822, there were approximately 31 Jews in New Bern, though there is little evidence that they established any Jewish communal institutions. One of the most notable 19th century Jews to live in New Bern was Dr. Nathan Meyer, who was forced to live in the town against his will. In 1864, Meyer, a Jewish soldier for the Union and a trained doctor, was captured in Plymouth, North Carolina. After seven months, he was paroled and ordered to work at the Foster General Hospital in New Bern. A month after the war ended, he closed the hospital and returned home to Hartford, Connecticut.

New Bern Jews were sometimes drawn into the racial politics of the late 19th century. Meyer Hahn had been born in Germany in 1838 and immigrated to New York City when he was 14 years old. In 1864, he moved to New Bern, where he established a livery stable. Hahn soon became interested in politics and was elected Sheriff of Craven County as a Republican in 1880, a position he held for three successive terms until 1886. At a time when most white Southerners supported the Democratic Party, Hahn cast his lot with the Republicans, who enlisted the support of freed slaves in North Carolina. In 1898, Meyer Hahn was appointed collector of customs for the port of New Bern. His nephew, Joseph Hahn, attracted local controversy during his political career. Joseph was elected Register of Deeds in 1892 and four years later, was elected Sheriff. He was a supporter of the North Carolina fusion movement, in which the Republican and Populist parties cooperated to win elections across the state. The movement’s success prompted the Democrats to begin to use race as a wedge issue. In New Bern, critics charged Hahn with being in favor of racial equality and accused him of being a traitor to the white race. Later, they forced him from office for his alleged racial heresy, although there is no evidence that his critics used his Jewishness against him during the conflict.

Most New Bern Jews avoided such divisive politics, concentrating instead on retail trade. Sam Lipman emigrated from Lithuania in 1885 and sold goods from a horse-drawn cart in Trenton, North Carolina. He eventually opened a dry goods store in New Bern, married Jennie Yoffie, and had three sons: Harry, Adolph, and Benjamin. He later opened a second store in New Bern that was run by his son Harry. Sam Lipman also sponsored his nephew, Joe, to come to New Bern. Joe opened a furniture store and married Celia Passman of Baltimore in 1911. They had a son, Elbert, who eventually went into the family business, which became known as Joe Lipman and Son Furniture. The store remained in business in New Bern for many decades, until it finally closed after the Twin Rivers Mall opened.

In the year 1822, there were approximately 31 Jews in New Bern, though there is little evidence that they established any Jewish communal institutions. One of the most notable 19th century Jews to live in New Bern was Dr. Nathan Meyer, who was forced to live in the town against his will. In 1864, Meyer, a Jewish soldier for the Union and a trained doctor, was captured in Plymouth, North Carolina. After seven months, he was paroled and ordered to work at the Foster General Hospital in New Bern. A month after the war ended, he closed the hospital and returned home to Hartford, Connecticut.

New Bern Jews were sometimes drawn into the racial politics of the late 19th century. Meyer Hahn had been born in Germany in 1838 and immigrated to New York City when he was 14 years old. In 1864, he moved to New Bern, where he established a livery stable. Hahn soon became interested in politics and was elected Sheriff of Craven County as a Republican in 1880, a position he held for three successive terms until 1886. At a time when most white Southerners supported the Democratic Party, Hahn cast his lot with the Republicans, who enlisted the support of freed slaves in North Carolina. In 1898, Meyer Hahn was appointed collector of customs for the port of New Bern. His nephew, Joseph Hahn, attracted local controversy during his political career. Joseph was elected Register of Deeds in 1892 and four years later, was elected Sheriff. He was a supporter of the North Carolina fusion movement, in which the Republican and Populist parties cooperated to win elections across the state. The movement’s success prompted the Democrats to begin to use race as a wedge issue. In New Bern, critics charged Hahn with being in favor of racial equality and accused him of being a traitor to the white race. Later, they forced him from office for his alleged racial heresy, although there is no evidence that his critics used his Jewishness against him during the conflict.

Most New Bern Jews avoided such divisive politics, concentrating instead on retail trade. Sam Lipman emigrated from Lithuania in 1885 and sold goods from a horse-drawn cart in Trenton, North Carolina. He eventually opened a dry goods store in New Bern, married Jennie Yoffie, and had three sons: Harry, Adolph, and Benjamin. He later opened a second store in New Bern that was run by his son Harry. Sam Lipman also sponsored his nephew, Joe, to come to New Bern. Joe opened a furniture store and married Celia Passman of Baltimore in 1911. They had a son, Elbert, who eventually went into the family business, which became known as Joe Lipman and Son Furniture. The store remained in business in New Bern for many decades, until it finally closed after the Twin Rivers Mall opened.

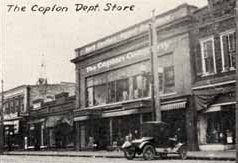

Another notable Jewish businessman in New Bern was Solomon Coplon. Coplan came to the United States from Russia, starting out as a traveling peddler in the Carolinas. He eventually moved to New Bern and opened a store in 1895. Coplon was among the first merchants to recognize the importance of advertising and filled the newspapers with interesting and original ads. When his sons were old enough to join the business, he changed the name of his store to S. Coplon and Sons. Coplan’s sons came up with the idea to focus on inexpensive merchandise, and created a chain of dollar stores called the Charles Store. Coplon’s sons also opened the Mother and Daughter Stores, which had locations all around the state. The original store in New Bern became the Coplon-Smith Company and operated until 1974 when it was destroyed by a fire.

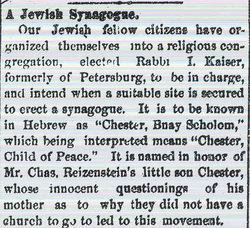

1893 article in New Bern newspaper

1893 article in New Bern newspaper

Organized Jewish Life in New Bern

The New Bern Jewish community remained rudimentary until the late 19th century when an influx of Jewish immigrants settled in the small port city. It was tragedy that prompted New Bern Jews to begin to organize. In November of 1877, two young sons of Oscar & Fannie Marks died; in response, a group called the United Hebrews of New Bern purchased land for a Jewish Cemetery. During the 1880s, New Bern Jews began to pray together. They sometimes met above Adolph and Meyer Hahn’s dry goods store; other times they gathered in a room above Oscar Marks’ store. By the late 19th century, New Bern Jews finally decided to establish a congregation. In 1893, they founded Congregation Chester B’nai Sholem and even hired Rabbi I. Kaiser from Petersburg, Virginia to lead them. Meyer Hahn was the group’s first president. The congregation was named in honor of Chester Reizenstein, the son of Charles Reizenstein. The young boy had once innocently asked his mother why they did not have a church to go to. In response to his inquiry and in memory of the boy, who had since passed away, the members put his first name at the beginning of the congregation’s title. At the time of its founding, the congregation consisted of 12 families and 50 total Jews.

In 1894, the congregation purchased land in New Bern upon which they would erect a synagogue. Among the trustees of the congregation were Meyer Hahn, Morris Sultan, Charles Reizenstein, and Oscar Marks. For the next 14 years, Congregation Chester B’nai Sholem would meet in a variety of downtown locations. In 1908, construction of the synagogue was started and completed in just four months. Two days after the opening of the synagogue, Emma Sultan and Sigmund Josepthal became the first couple to be married in the new temple. By the time of the temple’s dedication, the Jewish population of New Bern had grown to 125 people.

In 1909, the congregation hired a full-time rabbi, Harry A. Merfeld, to be Chester B’nai Sholem’s spiritual leader. Under his leadership, the congregation joined the Reform movement’s Union of American Hebrew Congregations and initiated the confirmation ceremony. However, Merfeld left New Bern in 1912, and the Jewish community would never again have a full-time rabbi. Chester B’nai Sholem would bring in students rabbis from Hebrew Union College to lead services during the High Holidays. Despite their affiliation with the Reform movement, some members of B’nai Sholem maintained Orthodox traditions. Local businessman Max Goldman served as shochet (kosher butcher) and mohel for the New Bern Jewish community until 1943.

The New Bern Jewish community remained rudimentary until the late 19th century when an influx of Jewish immigrants settled in the small port city. It was tragedy that prompted New Bern Jews to begin to organize. In November of 1877, two young sons of Oscar & Fannie Marks died; in response, a group called the United Hebrews of New Bern purchased land for a Jewish Cemetery. During the 1880s, New Bern Jews began to pray together. They sometimes met above Adolph and Meyer Hahn’s dry goods store; other times they gathered in a room above Oscar Marks’ store. By the late 19th century, New Bern Jews finally decided to establish a congregation. In 1893, they founded Congregation Chester B’nai Sholem and even hired Rabbi I. Kaiser from Petersburg, Virginia to lead them. Meyer Hahn was the group’s first president. The congregation was named in honor of Chester Reizenstein, the son of Charles Reizenstein. The young boy had once innocently asked his mother why they did not have a church to go to. In response to his inquiry and in memory of the boy, who had since passed away, the members put his first name at the beginning of the congregation’s title. At the time of its founding, the congregation consisted of 12 families and 50 total Jews.

In 1894, the congregation purchased land in New Bern upon which they would erect a synagogue. Among the trustees of the congregation were Meyer Hahn, Morris Sultan, Charles Reizenstein, and Oscar Marks. For the next 14 years, Congregation Chester B’nai Sholem would meet in a variety of downtown locations. In 1908, construction of the synagogue was started and completed in just four months. Two days after the opening of the synagogue, Emma Sultan and Sigmund Josepthal became the first couple to be married in the new temple. By the time of the temple’s dedication, the Jewish population of New Bern had grown to 125 people.

In 1909, the congregation hired a full-time rabbi, Harry A. Merfeld, to be Chester B’nai Sholem’s spiritual leader. Under his leadership, the congregation joined the Reform movement’s Union of American Hebrew Congregations and initiated the confirmation ceremony. However, Merfeld left New Bern in 1912, and the Jewish community would never again have a full-time rabbi. Chester B’nai Sholem would bring in students rabbis from Hebrew Union College to lead services during the High Holidays. Despite their affiliation with the Reform movement, some members of B’nai Sholem maintained Orthodox traditions. Local businessman Max Goldman served as shochet (kosher butcher) and mohel for the New Bern Jewish community until 1943.

Temple Chester B'nai Sholem

Temple Chester B'nai Sholem

Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler

The congregation remained small, with only 25 member families in 1930. The Jewish population of New Bern was only 67 in 1937. Nevertheless, the congregation remained active. In 1954, the congregation added a kitchen and schoolroom to the back of their synagogue. The Jewish women of the congregation formed a Sisterhood-Hadassah chapter in 1950. They raised money to send baby clothes and supplies to Israel. Minora Howard was the group’s first president. The Sisterhood discontinued its membership in Hadassah in the 1990s, though some of the individual women are still members.

From 1953 until the 1980s, Temple Chester B’nai Sholem was served by rabbis from Kinston, North Carolina. The first, Rabbi Dr. Jerome G. Tolochko, would come to the synagogue in New Bern on Tuesdays. Hebrew school was held in the afternoon and a worship service was held in the evening. Rabbi Tolochko also oversaw confirmation classes and bar mitzvah preparation for the young boys. Even after Rabbi Tolochko died in 1972, the rabbis from Kinston continued to serve New Bern. Among them were Rabbi Robert Shafran and Rabbi David Rose. When the Sunday school in New Bern closed, the members of Congregation Chester B’nai Sholem sent their children to Kinston’s religious school.

From 1953 until the 1980s, Temple Chester B’nai Sholem was served by rabbis from Kinston, North Carolina. The first, Rabbi Dr. Jerome G. Tolochko, would come to the synagogue in New Bern on Tuesdays. Hebrew school was held in the afternoon and a worship service was held in the evening. Rabbi Tolochko also oversaw confirmation classes and bar mitzvah preparation for the young boys. Even after Rabbi Tolochko died in 1972, the rabbis from Kinston continued to serve New Bern. Among them were Rabbi Robert Shafran and Rabbi David Rose. When the Sunday school in New Bern closed, the members of Congregation Chester B’nai Sholem sent their children to Kinston’s religious school.

The Jewish Community in New Bern Today

Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler

Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler

Today, B'nai Sholem remains an active congregation with 121 members from 76 households. The services are lay-led, and the congregation continues to worship in its 1908 synagogue.

Selected Sources

Seth Barret Tillman, "A Religious Test in America?: The 1809 Motion to Vacate Jacob Henry's North Carolina Legislative Seat—A Reevaluation of the Primary Sources," The North Carolina Historical Review, 98:1 (January 2021).

Seth Barret Tillman, "A Religious Test in America?: The 1809 Motion to Vacate Jacob Henry's North Carolina Legislative Seat—A Reevaluation of the Primary Sources," The North Carolina Historical Review, 98:1 (January 2021).