Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Durham/Chapel Hill North Carolina

Overview >> North Carolina >> Durham/Chapel Hill

Durham/Chapel Hill: Historical Overview

|

Jews have been an active part of the Durham and Chapel Hill community since the 1870s. Originally coming to the area as merchants, they have diversified into a variety of occupations, and established vibrant Jewish institutions. Durham and Chapel Hill Jews have contributed to the cultural, civic and economic life of the cities.

|

Stories of the Jewish Community in Durham and Chapel Hill

The Early Years: 1870s-1900

Although the first known Jewish merchants in Durham were a pair of Polish brothers, Abe and Jacob Goldstein, most of the new Jewish businesses were owned by immigrant German-speaking Jews or their descendants, whose families were already established in Richmond or other sizable Southern communities.

While Durham’s rapid growth provided a strong consumer base for the ten Jewish merchants that settled in the town prior to 1880, several elements discouraged Jewish arrivals. Financial turbulence, isolation from other Jewish communities, regular outbreaks of typhoid, and a glut of seedy businesses catering to newly urbanized factory workers all served as disincentives, especially Jews with families, to put down roots. Though the Jewish population grew throughout the last decades of the 1800s, the community also experienced outflows of both failed merchants and more successful families.

Although the first known Jewish merchants in Durham were a pair of Polish brothers, Abe and Jacob Goldstein, most of the new Jewish businesses were owned by immigrant German-speaking Jews or their descendants, whose families were already established in Richmond or other sizable Southern communities.

While Durham’s rapid growth provided a strong consumer base for the ten Jewish merchants that settled in the town prior to 1880, several elements discouraged Jewish arrivals. Financial turbulence, isolation from other Jewish communities, regular outbreaks of typhoid, and a glut of seedy businesses catering to newly urbanized factory workers all served as disincentives, especially Jews with families, to put down roots. Though the Jewish population grew throughout the last decades of the 1800s, the community also experienced outflows of both failed merchants and more successful families.

|

Some of the early Jewish Durhamites attempted to diversify into new trades, including a few who briefly sought to compete with Durham’s established tobacco families, but they primarily remained in the longstanding niches of dry goods retail and groceries. By the end of the 1880s they had shifted to specialty shops, especially in men’s clothing. These operations were largely financed through family networks, particularly in the cases of businessmen backed by family members in Baltimore or Richmond. As long as they maintained good credit, these merchants were well accepted in the local community, gaining entry into Masonic lodges and joining the local elite for card games. While Isaac Levy and Myer Summerfield were the most prominent Jewish businessmen of the period, with large homes in well-off neighborhoods, shop owners like Samuel Lehman and Louis Nachman also found economic success.

|

In nearby Chapel Hill, the University of North Carolina began attracting Jewish students from prosperous families in the state. In 1883, the school granted an honorary doctorate of Laws to Wilmington’s Rabbi Samuel Mendelsohn. The next year, Solomon Cohen Weill, also from Wilmington, became the university’s first Jewish teacher after being appointed to the position of acting professor of classical languages while pursuing dual bachelor’s degrees in arts and laws. From 1887 to 1895, Weill was also active on the UNC board of trustees. Chapel Hill’s Jewish population remained modest during and after these years. The town lacked industry, and the student population was not sufficient to support many retail operations. At the same time, Jews were not yet pulled toward academic positions, most of which would have been closed to them anyway.

Judea Reform.

Judea Reform. Photo courtesy of the Jewish Heritage Foundation of North Carolina

Early Organized Jewish Life

As more and more Jews moved to Durham, they began to worship together as a community. In 1878, a local newspaper mentioned that Durham Jews were observing Rosh Hashanah. Major holidays, visits by traveling rabbis, and Jewish life cycle ceremonies were increasingly reported in the press through the 1880s. The Jewish community took its first organizational steps in 1884, when Samuel Lehman, Jacob Levy, August Mohsberg, and Myer Summerfield purchased a 500 square foot piece of the town cemetery on Moorehead Road. First referred to as the Hebrew Burial Association and later the Jewish Cemetery Society, the group paved the way for the creation of the Durham Hebrew Congregation, which was founded in 1886 or 1887.

As more and more Jews moved to Durham, they began to worship together as a community. In 1878, a local newspaper mentioned that Durham Jews were observing Rosh Hashanah. Major holidays, visits by traveling rabbis, and Jewish life cycle ceremonies were increasingly reported in the press through the 1880s. The Jewish community took its first organizational steps in 1884, when Samuel Lehman, Jacob Levy, August Mohsberg, and Myer Summerfield purchased a 500 square foot piece of the town cemetery on Moorehead Road. First referred to as the Hebrew Burial Association and later the Jewish Cemetery Society, the group paved the way for the creation of the Durham Hebrew Congregation, which was founded in 1886 or 1887.

A Changing Community

Soon after the Durham Hebrew Congregation was founded, however, the local Jewish community faced economic troubles and a major demographic shift. In 1888, Blackwell’s Bank of Durham collapsed after overextending itself with easy credit. Among the affected businesses were a number of Jewish owned firms, leading to an exodus of the early families, especially those descended from German-speaking Jews. The Levy and Summerfield families remained past the first generation, as did a few less prosperous families. Yet by 1900, Eastern European Jews outnumbered the earlier arriving German immigrants in Durham.

The first significant number of Eastern European Jewish immigrants to settle in Durham was brought to the city in the 1880s by tobacco magnate Buck Duke, who needed skilled cigarette rollers for his new factories. The Duke Tobacco company, having fallen behind Bull Durham as a producer of pipe tobacco, decided to gamble on the new cigarette market. In order to secure workers for the new venture, Buck Duke traveled north to New York City in 1881, where he met Moses Gladstein, a Ukrainian Jew with experience in the industry. Though Gladstein had recently been fired from the Goodwin Tobacco factory for his role in an ongoing strike, Duke hired him along with a group of fellow strikers, assuming that the new hires would be no harder to manage than the native Southerners already employed by the company. Bull Durham soon followed suit and imported its own set of Jewish cigarette rollers to the city, bringing the total number to over 100.

As documented by Leonard Rogoff, however, the new arrivals’ experience in labor organization and leftist politics, and their outrage over the introduction of a new cigarette rolling machine led to the 1884 foundation of a local chapter of the Cigarmakers’ Progressive Union that included both Jewish and white Southern tobacco workers. Within a few years of their arrival, Duke began phasing out the trouble-making Jewish rollers, replacing them with native Southerners, including children. At the same time, changes in the national union forced the local chapter to disband. By the end of the 1880s, nearly all of the East European cigarette rollers had returned to New York City or other Northern destinations. Those who remained joined the bulk of their coreligionists as members of the growing merchant class.

Despite this disappearance of Durham’s short-lived Jewish working class, by 1900, Eastern European Jews and their families comprised over three percent of Durham’s population. Of these, half had arrived in the United States since 1889. During the 1880s and 1890s, the vast majority of Jewish immigrants seeking naturalization in Durham County came from Eastern Europe. Unlike their German-speaking predecessors, who crossed the Atlantic alone or with their immediate families, the Yiddish-speaking Jews that came to dominate the local population arrived in larger groups, one migrant setting the stage for a string of extended family and landsmen. As Leonard Rogoff points out, the bulk of these families originated in an area of the Pale of Settlement between Vilna, Lithuania and Dvinsk, Latvia. As a result, the growing Eastern European Jewish population was bound not only by general religious and cultural affinities, but through geographically specific traditions and even preexisting kinship ties. Most of the newest Jewish Durhamites had lived elsewhere in the United States before Durham.

As Durham’s population passed 18,000 in 1910, the city’s growing manufacturing operations attracted workers from the countryside. While these non-Jewish lower class families, regardless of race, might be employed entirely in tobacco and textile mills, their Jewish counterparts were heavily concentrated in commerce and trade, with very little representation in industrial work. Like other small cities, Durham drew migrant Jewish families in search of self-employment and an escape from the tenements and sweatshops of the urban North. In large part, ethnic and family associations allowed Jewish migrants to find employment and financing for commercial ventures. By 1900, 13 Jewish-owned groceries were situated in the vicinity of Main Street, in close proximity to the working class neighborhoods and company run mill villages that sprung up near the factories. Another common enterprise for Jewish Durhamites was the liquor store, a popular business in the industrial town, but, like grocery stores, only a small step up from peddling.

Whereas earlier Jewish merchants had lived above their stores or integrated into well-off neighborhoods, the East European immigrants clustered on Pine Street in the Bottoms, an enclave begun by the Goldstein brothers in the 1880s. The Goldsteins rented ten or more properties to other Jewish families in the low lying area that bordered Hayti, a working class African American neighborhood, and Durham’s red light district. Poverty limited the immigrants’ choice of housing, but life among family and landsmen in a Yiddish-speaking ghetto also provided comfort and support for the struggling community. As more Jews opened groceries catering specifically to black customers in Hayti, a few took up residence there, becoming the area’s only white inhabitants.

Soon after the Durham Hebrew Congregation was founded, however, the local Jewish community faced economic troubles and a major demographic shift. In 1888, Blackwell’s Bank of Durham collapsed after overextending itself with easy credit. Among the affected businesses were a number of Jewish owned firms, leading to an exodus of the early families, especially those descended from German-speaking Jews. The Levy and Summerfield families remained past the first generation, as did a few less prosperous families. Yet by 1900, Eastern European Jews outnumbered the earlier arriving German immigrants in Durham.

The first significant number of Eastern European Jewish immigrants to settle in Durham was brought to the city in the 1880s by tobacco magnate Buck Duke, who needed skilled cigarette rollers for his new factories. The Duke Tobacco company, having fallen behind Bull Durham as a producer of pipe tobacco, decided to gamble on the new cigarette market. In order to secure workers for the new venture, Buck Duke traveled north to New York City in 1881, where he met Moses Gladstein, a Ukrainian Jew with experience in the industry. Though Gladstein had recently been fired from the Goodwin Tobacco factory for his role in an ongoing strike, Duke hired him along with a group of fellow strikers, assuming that the new hires would be no harder to manage than the native Southerners already employed by the company. Bull Durham soon followed suit and imported its own set of Jewish cigarette rollers to the city, bringing the total number to over 100.

As documented by Leonard Rogoff, however, the new arrivals’ experience in labor organization and leftist politics, and their outrage over the introduction of a new cigarette rolling machine led to the 1884 foundation of a local chapter of the Cigarmakers’ Progressive Union that included both Jewish and white Southern tobacco workers. Within a few years of their arrival, Duke began phasing out the trouble-making Jewish rollers, replacing them with native Southerners, including children. At the same time, changes in the national union forced the local chapter to disband. By the end of the 1880s, nearly all of the East European cigarette rollers had returned to New York City or other Northern destinations. Those who remained joined the bulk of their coreligionists as members of the growing merchant class.

Despite this disappearance of Durham’s short-lived Jewish working class, by 1900, Eastern European Jews and their families comprised over three percent of Durham’s population. Of these, half had arrived in the United States since 1889. During the 1880s and 1890s, the vast majority of Jewish immigrants seeking naturalization in Durham County came from Eastern Europe. Unlike their German-speaking predecessors, who crossed the Atlantic alone or with their immediate families, the Yiddish-speaking Jews that came to dominate the local population arrived in larger groups, one migrant setting the stage for a string of extended family and landsmen. As Leonard Rogoff points out, the bulk of these families originated in an area of the Pale of Settlement between Vilna, Lithuania and Dvinsk, Latvia. As a result, the growing Eastern European Jewish population was bound not only by general religious and cultural affinities, but through geographically specific traditions and even preexisting kinship ties. Most of the newest Jewish Durhamites had lived elsewhere in the United States before Durham.

As Durham’s population passed 18,000 in 1910, the city’s growing manufacturing operations attracted workers from the countryside. While these non-Jewish lower class families, regardless of race, might be employed entirely in tobacco and textile mills, their Jewish counterparts were heavily concentrated in commerce and trade, with very little representation in industrial work. Like other small cities, Durham drew migrant Jewish families in search of self-employment and an escape from the tenements and sweatshops of the urban North. In large part, ethnic and family associations allowed Jewish migrants to find employment and financing for commercial ventures. By 1900, 13 Jewish-owned groceries were situated in the vicinity of Main Street, in close proximity to the working class neighborhoods and company run mill villages that sprung up near the factories. Another common enterprise for Jewish Durhamites was the liquor store, a popular business in the industrial town, but, like grocery stores, only a small step up from peddling.

Whereas earlier Jewish merchants had lived above their stores or integrated into well-off neighborhoods, the East European immigrants clustered on Pine Street in the Bottoms, an enclave begun by the Goldstein brothers in the 1880s. The Goldsteins rented ten or more properties to other Jewish families in the low lying area that bordered Hayti, a working class African American neighborhood, and Durham’s red light district. Poverty limited the immigrants’ choice of housing, but life among family and landsmen in a Yiddish-speaking ghetto also provided comfort and support for the struggling community. As more Jews opened groceries catering specifically to black customers in Hayti, a few took up residence there, becoming the area’s only white inhabitants.

Early Congregational Life

While Durham’s established German Jewish families found prestige as businessmen and civic leaders, they were displaced in the Jewish community. Having founded a burial society and the Durham Hebrew Congregation, this largely Reform contingent of Durham Jewry was supplanted as community leaders by 1892, when the congregation reconstituted itself as an Orthodox shul through a state charter. Though Myer Summerfield, a religiously observant immigrant from the German territories and leader of the burial society, served as the first congregation president, he was soon replaced by Polish-born Abe Goldstein, patriarch of the rising Yiddish-speaking population. Around the same time, Reverend Kolman Heillig, a Lithuanian native like many of the congregants, moved from Montreal to serve as the shul’s first religious leader. Heilling, like the “reverends” that followed him, was not an ordained rabbi, but a learned Jew who acted as a cantor, teacher, kosher butcher, and mohel.

Until the 1910s, religious services took place in rented rooms and store fronts. The local cheder—traditional religious school for boys—met in a livery stable on Pine Street. Despite these continuations of traditional Jewish life, younger and American-born Jews were already adopting fashions and lifestyles of their non-Jewish neighbors. Community members varied widely in their at home observance, but without a large enough population to sustain multiple congregations split along national origins or religious preferences, Durham’s Jews maintained a pragmatically traditionalist, if not completely Orthodox, style.

A decade into the 20th century, five out of six local Jews were American born. Since the 1890s, Durham Jews ran a Sunday school for the religious education of both boys and girls. In 1910 they introduced a Talmud Torah - a modern Hebrew school - and the English-language Sunday school. Though the institution occasionally floundered under weak leadership or poor finances, it demonstrated an attempt to pass on Jewish traditions to the next generation. The Sunday school was particularly unique for Durham in that it included both Reform and Orthodox Jews as teachers and students. Lily Kronheimer, of the prominent Reform family, exemplified this diversity with years of service to the school as both teacher and principal. The school enrolled 70 students in 1906, a number that increased to 105 in 1919. Women, not permitted to participate fully in most acts of public worship, found support and friendship in the Ladies Aid Society, founded in 1905. Among the notable leaders of this organization was Sarah Chai Miller, who led the group from 1915 to 1926. Monthly meetings of the Ladies Aid Society were attended by 35 or more women, and all of their business was done in Yiddish.

The Durham Hebrew Congregation faced a number of challenges in the early decades of the 20th century. The backwoods post did not appeal to most rabbis, few of whom were up to the challenge of balancing the traditionalist demands of the immigrant generation and the needs of young Americanized families. As a result, many reverends and rabbis served the community for only brief periods, as little as nine months in the case of Reverend Jacob Levenson, who arrived in 1903. In 1907, the congregation received their first ordained rabbi, Herman Ben Moshe of Richmond, but he only stayed for a year. Following a three year stint by R.N. Rosenberg, Rabbi Abraham Rabinowitz arrived in 1912. Rabinowitz was known for his cantorial excellence, weak English, and emotionally powerful Yiddish sermons.

Though the congregation boasted high rates of affiliation in 1900, the community faced an internal divide a year later, likely precipitated by disputes over the allotment of kosher meat. The dissident group founded their own congregation, Chevra B’nai Israel. While this breakaway group did not survive into 1903, the split epitomizes the factionalism that occasionally threatened to rend the tightly knit community. A similar rivalry led to the creation of a second congregation in the summer of 1913, when a group composed mostly of small businessmen formed Chevra B’nai Jacob. This incident probably involved recent increases in membership costs as well as personal and business disputes. The new faction lasted at least until the High Holidays of 1915. Along with these conflicts, home minyans occasionally formed when enough members took issue with others in the congregation.

In 1918, the Durham Jewish community, already in need of a larger home and now facing city plans to tear down their modest synagogue in order to reroute Liberty Street, struggled with the choice of whether to build a traditional and understated wooden shul or a prominent brick building more in line with the aesthetics of American Christian congregations. Following a contentious meeting, the congregation committed itself to an ambitious synagogue building project. Although the community faced a decline in population and economic challenges in the early years of the construction effort, they adopted the religiously progressive and American vision of the synagogue as a multipurpose facility that would serve cultural and educational needs in addition to its religious role. The cornerstone for the downtown synagogue was laid in 1920, with the participation of Gentile clergy and businessmen. When the building opened in 1921, it housed a newly incorporated congregation that had renamed itself Beth-El.

As Durham’s Jews found increasing economic success, they moved from their original Pine Street neighborhood in the bottoms to an area on Roxboro Street, on higher ground and the opposite side of the railroad tracks. Located within a few blocks of the Liberty Street synagogue that opened in 1904, as well as downtown stores, the area featured a number of two-story duplexes that Jewish families bought or rented. Leonard Rogoff notes that 30 to 35 Jewish families, around two-thirds of Durham’s Jewish population, lived in the area. Spread among white non-Jewish households, the Jewish homes were not known to Gentiles as a Jewish ghetto, but Jewish residents and their fellow congregants recognized the significant concentration of Jewish families. A kosher bakery, a delicatessen, and Jewish tailors and shoemakers all contributed to the cohesive feel of the new enclave.

Although the congregation’s membership numbers remained relatively stable from the 1910s through the 1930s, there was still a high degree of turnover within the community. Throughout these years, native Jews left Durham for educational and professional opportunities. Some families moved to bigger cities for more robust community life or to improve their children’s chances at finding a Jewish spouse. World War I, followed soon after by new immigration restrictions, all but ended the influx of European Jews. While Jewish families from elsewhere followed business and employment opportunities to Durham, the congregation lost members at both ends of the economic spectrum; the most successful businessmen took their fortunes elsewhere, and those on the lower economic rungs sought out more favorable locales. For all these reasons, the Jewish population failed to keep up with Durham’s continued growth.

While Durham’s established German Jewish families found prestige as businessmen and civic leaders, they were displaced in the Jewish community. Having founded a burial society and the Durham Hebrew Congregation, this largely Reform contingent of Durham Jewry was supplanted as community leaders by 1892, when the congregation reconstituted itself as an Orthodox shul through a state charter. Though Myer Summerfield, a religiously observant immigrant from the German territories and leader of the burial society, served as the first congregation president, he was soon replaced by Polish-born Abe Goldstein, patriarch of the rising Yiddish-speaking population. Around the same time, Reverend Kolman Heillig, a Lithuanian native like many of the congregants, moved from Montreal to serve as the shul’s first religious leader. Heilling, like the “reverends” that followed him, was not an ordained rabbi, but a learned Jew who acted as a cantor, teacher, kosher butcher, and mohel.

Until the 1910s, religious services took place in rented rooms and store fronts. The local cheder—traditional religious school for boys—met in a livery stable on Pine Street. Despite these continuations of traditional Jewish life, younger and American-born Jews were already adopting fashions and lifestyles of their non-Jewish neighbors. Community members varied widely in their at home observance, but without a large enough population to sustain multiple congregations split along national origins or religious preferences, Durham’s Jews maintained a pragmatically traditionalist, if not completely Orthodox, style.

A decade into the 20th century, five out of six local Jews were American born. Since the 1890s, Durham Jews ran a Sunday school for the religious education of both boys and girls. In 1910 they introduced a Talmud Torah - a modern Hebrew school - and the English-language Sunday school. Though the institution occasionally floundered under weak leadership or poor finances, it demonstrated an attempt to pass on Jewish traditions to the next generation. The Sunday school was particularly unique for Durham in that it included both Reform and Orthodox Jews as teachers and students. Lily Kronheimer, of the prominent Reform family, exemplified this diversity with years of service to the school as both teacher and principal. The school enrolled 70 students in 1906, a number that increased to 105 in 1919. Women, not permitted to participate fully in most acts of public worship, found support and friendship in the Ladies Aid Society, founded in 1905. Among the notable leaders of this organization was Sarah Chai Miller, who led the group from 1915 to 1926. Monthly meetings of the Ladies Aid Society were attended by 35 or more women, and all of their business was done in Yiddish.

The Durham Hebrew Congregation faced a number of challenges in the early decades of the 20th century. The backwoods post did not appeal to most rabbis, few of whom were up to the challenge of balancing the traditionalist demands of the immigrant generation and the needs of young Americanized families. As a result, many reverends and rabbis served the community for only brief periods, as little as nine months in the case of Reverend Jacob Levenson, who arrived in 1903. In 1907, the congregation received their first ordained rabbi, Herman Ben Moshe of Richmond, but he only stayed for a year. Following a three year stint by R.N. Rosenberg, Rabbi Abraham Rabinowitz arrived in 1912. Rabinowitz was known for his cantorial excellence, weak English, and emotionally powerful Yiddish sermons.

Though the congregation boasted high rates of affiliation in 1900, the community faced an internal divide a year later, likely precipitated by disputes over the allotment of kosher meat. The dissident group founded their own congregation, Chevra B’nai Israel. While this breakaway group did not survive into 1903, the split epitomizes the factionalism that occasionally threatened to rend the tightly knit community. A similar rivalry led to the creation of a second congregation in the summer of 1913, when a group composed mostly of small businessmen formed Chevra B’nai Jacob. This incident probably involved recent increases in membership costs as well as personal and business disputes. The new faction lasted at least until the High Holidays of 1915. Along with these conflicts, home minyans occasionally formed when enough members took issue with others in the congregation.

In 1918, the Durham Jewish community, already in need of a larger home and now facing city plans to tear down their modest synagogue in order to reroute Liberty Street, struggled with the choice of whether to build a traditional and understated wooden shul or a prominent brick building more in line with the aesthetics of American Christian congregations. Following a contentious meeting, the congregation committed itself to an ambitious synagogue building project. Although the community faced a decline in population and economic challenges in the early years of the construction effort, they adopted the religiously progressive and American vision of the synagogue as a multipurpose facility that would serve cultural and educational needs in addition to its religious role. The cornerstone for the downtown synagogue was laid in 1920, with the participation of Gentile clergy and businessmen. When the building opened in 1921, it housed a newly incorporated congregation that had renamed itself Beth-El.

As Durham’s Jews found increasing economic success, they moved from their original Pine Street neighborhood in the bottoms to an area on Roxboro Street, on higher ground and the opposite side of the railroad tracks. Located within a few blocks of the Liberty Street synagogue that opened in 1904, as well as downtown stores, the area featured a number of two-story duplexes that Jewish families bought or rented. Leonard Rogoff notes that 30 to 35 Jewish families, around two-thirds of Durham’s Jewish population, lived in the area. Spread among white non-Jewish households, the Jewish homes were not known to Gentiles as a Jewish ghetto, but Jewish residents and their fellow congregants recognized the significant concentration of Jewish families. A kosher bakery, a delicatessen, and Jewish tailors and shoemakers all contributed to the cohesive feel of the new enclave.

Although the congregation’s membership numbers remained relatively stable from the 1910s through the 1930s, there was still a high degree of turnover within the community. Throughout these years, native Jews left Durham for educational and professional opportunities. Some families moved to bigger cities for more robust community life or to improve their children’s chances at finding a Jewish spouse. World War I, followed soon after by new immigration restrictions, all but ended the influx of European Jews. While Jewish families from elsewhere followed business and employment opportunities to Durham, the congregation lost members at both ends of the economic spectrum; the most successful businessmen took their fortunes elsewhere, and those on the lower economic rungs sought out more favorable locales. For all these reasons, the Jewish population failed to keep up with Durham’s continued growth.

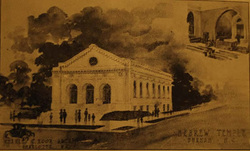

Beth-El Synagogue.

Beth-El Synagogue. Photo courtesy of the Jewish Heritage Foundation of North Carolina.

Jewish Life at UNC & Duke

Though fewer than 20 of the University of North Carolina's 1,000 or so students were Jewish during the 1910s, Jewish students did manage to organize their own campus organization. In 1912, undergraduate Samuel Newman founded a Hebrew Culture Society on campus, the first Jewish student organization at a Southern university. After enrolling nearly all of school’s 16 Jewish students, the group affiliated with the Intercollegiate Menorah Association. Despite the objections of the YMCA national leadership, UNC’s YMCA, then under the direction of future university president Frank Graham, contributed office space to the new Jewish group. At Trinity College, which would later change its name to Duke University, quotas limited the number of Jewish students admitted from out of town, though local Jews were generally thought to be exempt from such exclusion. Fanny Goldstein graduated from Trinity in 1911 near the top of her class.

As small numbers of Northern Jews began attending the colleges, especially UNC, campus Jewish life became more organized. Jews founded their own fraternities and sororities to compensate for their exclusion from these Gentile social organizations. UNC’s first Jewish fraternity, formed in 1924, was a chapter of TEP. The group caused anxiety among local and university-affiliated Jews for raising too high a profile, and it was not immediately legitimated by the university’s fraternity council. TEP’s members were, for the most part, sons of Yiddish-speaking immigrants from Eastern Europe. ZBT followed in 1927, catering to students from more established and acculturated families. At Duke, the only five enrolled Jewish men began a fraternity called Pente in 1926. Three years later, the group became a chapter of Phi Sigma Delta.

Even as the universities drew larger numbers of Jewish students, they also offered opportunities for more permanent Jewish residents. James B. Duke’s $40 million gift to the newly established university created a variety of faculty and staff positions, as well as significant numbers of jobs for employees involved in building and maintaining the greatly expanded campus. Though few of these jobs went directly to Jews, the influx of workers meant more business for Durham’s Jewish merchants. Similarly, growing enrollment at UNC guaranteed a consumer base for Chapel Hill’s Jewish merchants, whose numbers grew from two in 1916, to 13 in 1927, and 32 in 1937, at which point a stable community emerged. The scholastic atmosphere also fostered a cosmopolitanism that contributed to the success of Jaffe’s kosher bakery in Durham and Harry’s, a non-kosher but markedly Jewish delicatessen in Chapel Hill that became a popular meeting place for local intellectuals.

Though fewer than 20 of the University of North Carolina's 1,000 or so students were Jewish during the 1910s, Jewish students did manage to organize their own campus organization. In 1912, undergraduate Samuel Newman founded a Hebrew Culture Society on campus, the first Jewish student organization at a Southern university. After enrolling nearly all of school’s 16 Jewish students, the group affiliated with the Intercollegiate Menorah Association. Despite the objections of the YMCA national leadership, UNC’s YMCA, then under the direction of future university president Frank Graham, contributed office space to the new Jewish group. At Trinity College, which would later change its name to Duke University, quotas limited the number of Jewish students admitted from out of town, though local Jews were generally thought to be exempt from such exclusion. Fanny Goldstein graduated from Trinity in 1911 near the top of her class.

As small numbers of Northern Jews began attending the colleges, especially UNC, campus Jewish life became more organized. Jews founded their own fraternities and sororities to compensate for their exclusion from these Gentile social organizations. UNC’s first Jewish fraternity, formed in 1924, was a chapter of TEP. The group caused anxiety among local and university-affiliated Jews for raising too high a profile, and it was not immediately legitimated by the university’s fraternity council. TEP’s members were, for the most part, sons of Yiddish-speaking immigrants from Eastern Europe. ZBT followed in 1927, catering to students from more established and acculturated families. At Duke, the only five enrolled Jewish men began a fraternity called Pente in 1926. Three years later, the group became a chapter of Phi Sigma Delta.

Even as the universities drew larger numbers of Jewish students, they also offered opportunities for more permanent Jewish residents. James B. Duke’s $40 million gift to the newly established university created a variety of faculty and staff positions, as well as significant numbers of jobs for employees involved in building and maintaining the greatly expanded campus. Though few of these jobs went directly to Jews, the influx of workers meant more business for Durham’s Jewish merchants. Similarly, growing enrollment at UNC guaranteed a consumer base for Chapel Hill’s Jewish merchants, whose numbers grew from two in 1916, to 13 in 1927, and 32 in 1937, at which point a stable community emerged. The scholastic atmosphere also fostered a cosmopolitanism that contributed to the success of Jaffe’s kosher bakery in Durham and Harry’s, a non-kosher but markedly Jewish delicatessen in Chapel Hill that became a popular meeting place for local intellectuals.

The Great Depression & WWII

Rabbi Chaim Williamofsky took over the Beth-El pulpit in 1930, after serving in Hendersonville, North Carolina. Having graduated from yeshiva and received his ordination in Poland, Williamofsky first arrived in North Carolina in 1925. The bearded rabbi was popular among congregants and non-Jews, and remained with the congregation for seven years. Unfortunately, the congregation could not afford an adequate salary for Williamofsky to support his large family. Rabbi Israel Mowshowitz, a graduate of Yeshiva College and the first Durham rabbi with a college education, succeeded Williamofsky. Mowshowitz delivered sermons in English for the first time in congregational history. Though few of the congregants abstained from driving or using electricity on Shabbat, members of the old guard were apprehensive of Mowshowitz, who moved congregational practice from Eastern European Orthodoxy toward Modern Orthodox ritual.

The Great Depression led to setbacks for Durham’s Jews, who had made significant gains in the 1920s. The community persevered, though, in part through the organization of a Hebrew Benevolent Society that offered loans of $500 to $1,000 to merchants in distress. Economic instability also led to labor strife in the factory town. The Evans family, owners of United Dollar Store, were among Jewish leaders who offered notable support for workers in the major 1934 textile strike. For Jewish merchants, such actions fit the spirit of the times but also demonstrated their interest in maintaining strong relations with their working class customers.

In the late 1930s, Durham Jews still made their livings largely as self-employed businessmen. A few worked for larger companies or were involved in more novel ventures like selling auto parts, but traditionally, Jewish businesses selling clothing, groceries, and scrap iron predominated. A handful of local Jews owned manufacturing operations, while others had entered the professional world as professors or lawyers. One local Jew was a medical x-ray specialist. Some jobs were still more or less closed to Jews. Although there were exceptions, Jews did not hold jobs with the public schools, particular department stores, tobacco companies, or the Duke University administration. They were welcome in the banking industry, however, in contrast with the general trend of Jewish exclusion from American financial firms.

Though economic troubles forced a decline in the Durham Jewish community’s level of synagogue affiliation, local Jews continued to hold strong associations. Young Jews belonged to local youth group chapters and participated in weekend trips to social events in Asheville, Charlotte, Wilmington, and other Jewish centers. The Durham and Raleigh Sisterhoods took turns putting on annual Thanksgiving dances that drew hundreds of young Jews, not only from within the state, but Virginia and South Carolina as well. These state and regional networks were further strengthened during the summers, when friends and families met on visits to Carolina Beach near Wilmington.

The 1930s were also a time of increasing activity for Jewish adults in Durham. Like other parts of the country, local and regional Jewish organizations increased in number, scope, and membership. While congregational enrollment and synagogue attendance declined, civic life in groups like the North Carolina Association of Jewish Women, B’nai Brith, and Mizrachi, a group for observant Zionists, became stronger than ever, especially under the leadership of powerful personalities like Solomon Dworsky and Sara Evans.

The 1930s saw major increases in Jewish enrollment at UNC. Duke was a Methodist University that, according to Leonard Rogoff, seems to have imposed a 3% cap on Jewish enrollment throughout the decade. The University of North Carolina, however, saw Jewish enrollment rise to 15% of the 1936 freshman class. As more Northern Jews found their way to UNC, both Jewish and Gentile members of the campus community welcomed them with some ambivalence. In 1938, over 80% of the University’s 249 Jewish students came from the North. This contingent, drawn by easier admission and lower tuition, did not plan to make permanent homes in the South. Likely coming from less acculturated families in more insular and urban Jewish enclaves than their Southern co-religionists, they were also newcomers to the courteous manners and conservative mores of the South. It was partially in response to concerns over these students that North Carolina Jews opened a Hillel Chapter on the UNC campus in 1936. UNC Hillel, the eleventh chapter of the national group, introduced organized Reform worship to the area on Rosh Hashanah of its inaugural year. The founders intended for the group not only to strengthen Jewish identity of students but also to ease Northern Jews’ adjustment to the South.

The 1930s also saw the introduction of significant numbers of Jewish instructors to Duke and UNC. Duke Medical School, opened in 1930, established a noticeable Jewish presence among local academics for the first time. Both institutions continued to hire more Jewish professors, but these new arrivals remained concentrated in health related fields and the sciences. Among the most notable was UNC’s Milton Rosenau, president of the Department of Public Health, and its first dean upon Public Health’s promotion to a school within the university system. Many of these instructors and researchers, however, did not affiliate with Durham Beth-El, the closest congregation. Rosenau, active on the national boards of the AJC and AUHC, never became active in the local Jewish community.

When World War II came to America, it brought major changes to Durham and local Jews. Within weeks of the United States’ entrance into the war, the federal government began construction of Camp Butner, only twelve miles from Durham. Upon completion, the base housed 50,000 soldiers, many of whom were Jewish. These temporary residents were welcomed by the local Jewish community with dances and home hospitality for holidays. With professors in the sciences, especially physics, called into service for military projects, Jewish graduate students filled major teaching roles at both UNC and Duke.

Rabbi Chaim Williamofsky took over the Beth-El pulpit in 1930, after serving in Hendersonville, North Carolina. Having graduated from yeshiva and received his ordination in Poland, Williamofsky first arrived in North Carolina in 1925. The bearded rabbi was popular among congregants and non-Jews, and remained with the congregation for seven years. Unfortunately, the congregation could not afford an adequate salary for Williamofsky to support his large family. Rabbi Israel Mowshowitz, a graduate of Yeshiva College and the first Durham rabbi with a college education, succeeded Williamofsky. Mowshowitz delivered sermons in English for the first time in congregational history. Though few of the congregants abstained from driving or using electricity on Shabbat, members of the old guard were apprehensive of Mowshowitz, who moved congregational practice from Eastern European Orthodoxy toward Modern Orthodox ritual.

The Great Depression led to setbacks for Durham’s Jews, who had made significant gains in the 1920s. The community persevered, though, in part through the organization of a Hebrew Benevolent Society that offered loans of $500 to $1,000 to merchants in distress. Economic instability also led to labor strife in the factory town. The Evans family, owners of United Dollar Store, were among Jewish leaders who offered notable support for workers in the major 1934 textile strike. For Jewish merchants, such actions fit the spirit of the times but also demonstrated their interest in maintaining strong relations with their working class customers.

In the late 1930s, Durham Jews still made their livings largely as self-employed businessmen. A few worked for larger companies or were involved in more novel ventures like selling auto parts, but traditionally, Jewish businesses selling clothing, groceries, and scrap iron predominated. A handful of local Jews owned manufacturing operations, while others had entered the professional world as professors or lawyers. One local Jew was a medical x-ray specialist. Some jobs were still more or less closed to Jews. Although there were exceptions, Jews did not hold jobs with the public schools, particular department stores, tobacco companies, or the Duke University administration. They were welcome in the banking industry, however, in contrast with the general trend of Jewish exclusion from American financial firms.

Though economic troubles forced a decline in the Durham Jewish community’s level of synagogue affiliation, local Jews continued to hold strong associations. Young Jews belonged to local youth group chapters and participated in weekend trips to social events in Asheville, Charlotte, Wilmington, and other Jewish centers. The Durham and Raleigh Sisterhoods took turns putting on annual Thanksgiving dances that drew hundreds of young Jews, not only from within the state, but Virginia and South Carolina as well. These state and regional networks were further strengthened during the summers, when friends and families met on visits to Carolina Beach near Wilmington.

The 1930s were also a time of increasing activity for Jewish adults in Durham. Like other parts of the country, local and regional Jewish organizations increased in number, scope, and membership. While congregational enrollment and synagogue attendance declined, civic life in groups like the North Carolina Association of Jewish Women, B’nai Brith, and Mizrachi, a group for observant Zionists, became stronger than ever, especially under the leadership of powerful personalities like Solomon Dworsky and Sara Evans.

The 1930s saw major increases in Jewish enrollment at UNC. Duke was a Methodist University that, according to Leonard Rogoff, seems to have imposed a 3% cap on Jewish enrollment throughout the decade. The University of North Carolina, however, saw Jewish enrollment rise to 15% of the 1936 freshman class. As more Northern Jews found their way to UNC, both Jewish and Gentile members of the campus community welcomed them with some ambivalence. In 1938, over 80% of the University’s 249 Jewish students came from the North. This contingent, drawn by easier admission and lower tuition, did not plan to make permanent homes in the South. Likely coming from less acculturated families in more insular and urban Jewish enclaves than their Southern co-religionists, they were also newcomers to the courteous manners and conservative mores of the South. It was partially in response to concerns over these students that North Carolina Jews opened a Hillel Chapter on the UNC campus in 1936. UNC Hillel, the eleventh chapter of the national group, introduced organized Reform worship to the area on Rosh Hashanah of its inaugural year. The founders intended for the group not only to strengthen Jewish identity of students but also to ease Northern Jews’ adjustment to the South.

The 1930s also saw the introduction of significant numbers of Jewish instructors to Duke and UNC. Duke Medical School, opened in 1930, established a noticeable Jewish presence among local academics for the first time. Both institutions continued to hire more Jewish professors, but these new arrivals remained concentrated in health related fields and the sciences. Among the most notable was UNC’s Milton Rosenau, president of the Department of Public Health, and its first dean upon Public Health’s promotion to a school within the university system. Many of these instructors and researchers, however, did not affiliate with Durham Beth-El, the closest congregation. Rosenau, active on the national boards of the AJC and AUHC, never became active in the local Jewish community.

When World War II came to America, it brought major changes to Durham and local Jews. Within weeks of the United States’ entrance into the war, the federal government began construction of Camp Butner, only twelve miles from Durham. Upon completion, the base housed 50,000 soldiers, many of whom were Jewish. These temporary residents were welcomed by the local Jewish community with dances and home hospitality for holidays. With professors in the sciences, especially physics, called into service for military projects, Jewish graduate students filled major teaching roles at both UNC and Duke.

Postwar Prosperity

The war years also marked the beginning of the decline of the Jewish neighborhood on Roxboro Street. Durham’s Jews, more affluent than ever and emerging as major civic leaders, joined other white Durhamites in the growing suburbs. This change reflected a shift in status even as it marked the trend toward Conservative Judaism as decreasing numbers of Durham Jews were able to walk to synagogue. At Duke, Judaism earned its place as a serious subject of study as the university became the first Southern school to hire a full-time instructor in Jewish Studies, a teaching post funded by North Carolina’s Stern and Nachamson families.

Durham emerged as a strong center of support for Zionism and Jewish statehood. From the mid-1940s through the 1950s, Durham Hadassah thrived under the leadership of Sara Nachamson Evans, who held the national vice presidency from 1954 to 1957. Following the establishment of the State of Israel, local Jews advocated for support from local non-Jews. Much of the local youth programming and religious education focused on Israel, and any prospective rabbi was expected to act as a Middle East expert and pro-Zionist spokesman in the greater community. On campus, Zionism drew support as well, with active chapters of the Intercollegiate Zionist Federation of America at both Duke and UNC.

In the 1940s and 1950s, growing numbers of Jewish faculty at Duke and UNC foreshadowed the academic future of the area’s Jewish community, but many Jewish academics remained distant from the merchant class core of Jewish life in Durham. Locals often perceived university affiliated newcomers as haughty or overly assimilated. Faculty, both American-born Jews and German émigrés, had little interest in the traditional leaning congregation in Durham. Beth-El Rabbi Israel Moshowitz, a doctoral student at Duke, helped bridge this divide, as did the Evans family, who reached out to newly arrived scholars. A few academic families became involved at Beth-El, but others formed their own social circles or attended campus Hillel at Duke or UNC as their primary congregations.

Even as the number of local Jews with university jobs rose, the formerly dominant merchant class began to decline. Consolidation and public disfavor brought a slow decline to local tobacco processing, while textile operations suffered under worker malcontent and outsourcing to foreign factories. Downtown ceased to be a retail center. Jake Margolis moved from the grocery trade into insurance sales. Leon Dworsky abandoned his pawn shop, inherited from his father, for a camera repair business, then a job as a computer programmer. Some Jewish retailers moved to the malls that sprang up around town. Those with large holdings in real estate used their assets to ease the shift away from trade.

By the late 1940s, Durham Jews no longer provided enough business to sustain a shochet. The synagogue, with Jewish education and youth programming as its most vibrant areas of activity, replaced the home as the site of transmission for Jewish culture and religion. Friday evenings outdrew Saturday mornings, the province of the traditionalist bloc. Holiday services were conducted in a Conservative style, more accessible to the larger crowds that attended. Younger and more religiously liberal congregants saw compromise as a necessary step that would attract the faculty population that was clearly the future of the local Jewish community. Though Beth-El was not yet ready to affiliate with the United Synagogue of America, the Conservative Movement’s national organization, they hired a Jewish Theological Seminary graduate, Rabbi Simon Glustrom, in 1948. Although two of the string of rabbis that led the synagogue through the 1950s were Orthodox, the community’s expectations were changing.

In the early 1950s, the opening of a large Veteran’s Association hospital in Durham and North Carolina Memorial Hospital in Chapel Hill marked the rise of the area as a center for healthcare and medical research. Around this time, UNC and Duke partnered with North Carolina State University in Raleigh to establish the Research Triangle, further developing the national reputations of the schools. By 1958, 20% of local Jewish households included at least one member holding a doctorate. Six years later, this figure reached 40% as 105 of 271 Jewish homes contained a Ph.D. In both cities, but Chapel Hill especially, Jewish families spread out among new suburbs and subdivisions, blending in easily with the growing population. Country clubs and other groups opened their doors to a greater extent than ever before.

E.J. “Mutt” Evans, who spent 12 years as the mayor of Durham, exemplifies the rising status of Jews. Elected in 1950 under the campaign slogan “equal representation to all people,” Evans was initially nominated with the help of African American business leaders. He served Durham from 1951 to 1963, helping to navigate the city through the difficult years of the integration crisis. More interested in economic development than in the racial politics adopted by the Civil Rights Movement, Evans began his tenure as a liberal, but appeared something of a centrist with the radicalization of minority and student movements. Though some white Christian voters were initially skeptical, they supported him in greater proportions in each of his five reelections. Mutt’s son Eli Evans has become known as the “poet laureate” of Southern Jews after writing such books as The Provincials and The Lonely Days Were Sundays.

The war years also marked the beginning of the decline of the Jewish neighborhood on Roxboro Street. Durham’s Jews, more affluent than ever and emerging as major civic leaders, joined other white Durhamites in the growing suburbs. This change reflected a shift in status even as it marked the trend toward Conservative Judaism as decreasing numbers of Durham Jews were able to walk to synagogue. At Duke, Judaism earned its place as a serious subject of study as the university became the first Southern school to hire a full-time instructor in Jewish Studies, a teaching post funded by North Carolina’s Stern and Nachamson families.

Durham emerged as a strong center of support for Zionism and Jewish statehood. From the mid-1940s through the 1950s, Durham Hadassah thrived under the leadership of Sara Nachamson Evans, who held the national vice presidency from 1954 to 1957. Following the establishment of the State of Israel, local Jews advocated for support from local non-Jews. Much of the local youth programming and religious education focused on Israel, and any prospective rabbi was expected to act as a Middle East expert and pro-Zionist spokesman in the greater community. On campus, Zionism drew support as well, with active chapters of the Intercollegiate Zionist Federation of America at both Duke and UNC.

In the 1940s and 1950s, growing numbers of Jewish faculty at Duke and UNC foreshadowed the academic future of the area’s Jewish community, but many Jewish academics remained distant from the merchant class core of Jewish life in Durham. Locals often perceived university affiliated newcomers as haughty or overly assimilated. Faculty, both American-born Jews and German émigrés, had little interest in the traditional leaning congregation in Durham. Beth-El Rabbi Israel Moshowitz, a doctoral student at Duke, helped bridge this divide, as did the Evans family, who reached out to newly arrived scholars. A few academic families became involved at Beth-El, but others formed their own social circles or attended campus Hillel at Duke or UNC as their primary congregations.

Even as the number of local Jews with university jobs rose, the formerly dominant merchant class began to decline. Consolidation and public disfavor brought a slow decline to local tobacco processing, while textile operations suffered under worker malcontent and outsourcing to foreign factories. Downtown ceased to be a retail center. Jake Margolis moved from the grocery trade into insurance sales. Leon Dworsky abandoned his pawn shop, inherited from his father, for a camera repair business, then a job as a computer programmer. Some Jewish retailers moved to the malls that sprang up around town. Those with large holdings in real estate used their assets to ease the shift away from trade.

By the late 1940s, Durham Jews no longer provided enough business to sustain a shochet. The synagogue, with Jewish education and youth programming as its most vibrant areas of activity, replaced the home as the site of transmission for Jewish culture and religion. Friday evenings outdrew Saturday mornings, the province of the traditionalist bloc. Holiday services were conducted in a Conservative style, more accessible to the larger crowds that attended. Younger and more religiously liberal congregants saw compromise as a necessary step that would attract the faculty population that was clearly the future of the local Jewish community. Though Beth-El was not yet ready to affiliate with the United Synagogue of America, the Conservative Movement’s national organization, they hired a Jewish Theological Seminary graduate, Rabbi Simon Glustrom, in 1948. Although two of the string of rabbis that led the synagogue through the 1950s were Orthodox, the community’s expectations were changing.

In the early 1950s, the opening of a large Veteran’s Association hospital in Durham and North Carolina Memorial Hospital in Chapel Hill marked the rise of the area as a center for healthcare and medical research. Around this time, UNC and Duke partnered with North Carolina State University in Raleigh to establish the Research Triangle, further developing the national reputations of the schools. By 1958, 20% of local Jewish households included at least one member holding a doctorate. Six years later, this figure reached 40% as 105 of 271 Jewish homes contained a Ph.D. In both cities, but Chapel Hill especially, Jewish families spread out among new suburbs and subdivisions, blending in easily with the growing population. Country clubs and other groups opened their doors to a greater extent than ever before.

E.J. “Mutt” Evans, who spent 12 years as the mayor of Durham, exemplifies the rising status of Jews. Elected in 1950 under the campaign slogan “equal representation to all people,” Evans was initially nominated with the help of African American business leaders. He served Durham from 1951 to 1963, helping to navigate the city through the difficult years of the integration crisis. More interested in economic development than in the racial politics adopted by the Civil Rights Movement, Evans began his tenure as a liberal, but appeared something of a centrist with the radicalization of minority and student movements. Though some white Christian voters were initially skeptical, they supported him in greater proportions in each of his five reelections. Mutt’s son Eli Evans has become known as the “poet laureate” of Southern Jews after writing such books as The Provincials and The Lonely Days Were Sundays.

A Reform Congregation

Reform Jews in the area first organized in 1961, with the foundation of Judea Reform Congregation in Durham. The group began with meetings and services in members’ homes. Composed of both acculturated descendants of Eastern European merchants and more recent arrivals with professional and academic backgrounds, they initially held High Holiday services at York Chapel on the Duke University Campus. From the outset, the new congregation involved Chapel Hill Jews, occasionally holding services there prior to the construction of a temple. While Beth-El continued its slow transformation from Orthodoxy to Conservatism, Judea Reform allowed for fuller participation of women and adopted an inclusive approach to intermarried couples and their children. The congregation did not require yarmulkes or talitot of its male worshipers and originally held Shabbat morning services only in the instance of b’nei mitzvah. The congregation soon purchased land for a future synagogue in Durham, but in proximity to U.S. Highway 15-501, the major route from Chapel Hill.

With the opening of Research Triangle Park in 1959, the area attracted new science-related firms, as well as foreign businesses and investors. Subsequent growth, especially in the area of high-tech business, exemplifies the Sunbelt expansion that took place from the 1960s on in parts of the American South. Like other such centers, though on a smaller scale, Durham and Chapel Hill (and Raleigh) have witnessed a correlative rise in Jewish population. Judea Reform’s membership boomed. Its first building, opened in 1971, was designed with expansion in mind, and the new addition was started within six years. At the same time, rising numbers of older Jews, both locals and the parents of newly arrived professionals and academics, made the area a center of Jewish retirement. Judea Reform subsequently founded its own cemetery in 1982, an alternative to the Orthodox burial practices maintained by Beth-El’s chevra kadisha. In 1988, Judea Reform, once again in need of more space, constructed the Mel and Zora Rashkin Building.

Beth-El Synagogue continued to grow and change as well. Following a move by the United Synagogue of America to allow full participation by female worshipers in Conservative minyans, Beth-El began monthly egalitarian services on Shabbat mornings. The congregation also allowed women to receive aliyot on the second days of two-day holidays. In 1976, with the departure of Rabbi Herbert Berger, who had served the congregation since the 1950s, the congregation moved irrevocably in the direction of egalitarian Conservative practice, with the hiring of Rabbi Stephen Sager, a graduate of the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College. All services in the main sanctuary were to recognize women as equal participants. Soon after, women ascended to leadership positions in the community as well. Traditional congregants who opposed these changes met in a downstairs room for Orthodox services. The Durham Orthodox Kehillah, established in 1979 and affiliated with the Orthodox Union, remains administratively a part of Beth-El. The kehillah was initially led by Leon Dworsky.

Reform Jews in the area first organized in 1961, with the foundation of Judea Reform Congregation in Durham. The group began with meetings and services in members’ homes. Composed of both acculturated descendants of Eastern European merchants and more recent arrivals with professional and academic backgrounds, they initially held High Holiday services at York Chapel on the Duke University Campus. From the outset, the new congregation involved Chapel Hill Jews, occasionally holding services there prior to the construction of a temple. While Beth-El continued its slow transformation from Orthodoxy to Conservatism, Judea Reform allowed for fuller participation of women and adopted an inclusive approach to intermarried couples and their children. The congregation did not require yarmulkes or talitot of its male worshipers and originally held Shabbat morning services only in the instance of b’nei mitzvah. The congregation soon purchased land for a future synagogue in Durham, but in proximity to U.S. Highway 15-501, the major route from Chapel Hill.

With the opening of Research Triangle Park in 1959, the area attracted new science-related firms, as well as foreign businesses and investors. Subsequent growth, especially in the area of high-tech business, exemplifies the Sunbelt expansion that took place from the 1960s on in parts of the American South. Like other such centers, though on a smaller scale, Durham and Chapel Hill (and Raleigh) have witnessed a correlative rise in Jewish population. Judea Reform’s membership boomed. Its first building, opened in 1971, was designed with expansion in mind, and the new addition was started within six years. At the same time, rising numbers of older Jews, both locals and the parents of newly arrived professionals and academics, made the area a center of Jewish retirement. Judea Reform subsequently founded its own cemetery in 1982, an alternative to the Orthodox burial practices maintained by Beth-El’s chevra kadisha. In 1988, Judea Reform, once again in need of more space, constructed the Mel and Zora Rashkin Building.

Beth-El Synagogue continued to grow and change as well. Following a move by the United Synagogue of America to allow full participation by female worshipers in Conservative minyans, Beth-El began monthly egalitarian services on Shabbat mornings. The congregation also allowed women to receive aliyot on the second days of two-day holidays. In 1976, with the departure of Rabbi Herbert Berger, who had served the congregation since the 1950s, the congregation moved irrevocably in the direction of egalitarian Conservative practice, with the hiring of Rabbi Stephen Sager, a graduate of the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College. All services in the main sanctuary were to recognize women as equal participants. Soon after, women ascended to leadership positions in the community as well. Traditional congregants who opposed these changes met in a downstairs room for Orthodox services. The Durham Orthodox Kehillah, established in 1979 and affiliated with the Orthodox Union, remains administratively a part of Beth-El. The kehillah was initially led by Leon Dworsky.

Greater Jewish Presence at UNC & Duke

From the 1950s on, Jews at UNC and Duke grew simultaneously more comfortable outwardly identifying as Jews and less conspicuously divided from peers among the student body and faculty. The establishment of a Hillel House on the UNC campus in 1951 marked the accepted status of the Jewish organization. The university ended its practice of asking incoming students about religious preferences in 1955, information that previously allowed housing administration to lump Jewish students together in particular dormitories. In 1957, basketball star Lenny Rosenbluth improved the image of New York Jews on campus, leading the team to an NCAA championship and earning National Player of the Year honors. Some professional bias persisted at Duke University Schools of Medicine and Law, as well as other departments at both universities, until at least the 1960s. In the last decades of the 20th century, however, Jews were well represented in administrative posts at both institutions.

At Duke, Jewish enrollment has risen as a percent of the total population as the university has come to compete with the Ivy League for prestige, while UNC’s rising standards for out-of-state students contributed in the 1990s to a decrease in Jewish students as a percentage of the total population. In terms of real numbers, both campuses have seen an increase in Jewish enrollment, with a combined total of over 2,700 students. Recently, Duke has reinvigorated its Jewish Studies program, originally established in the early 1970s. UNC founded the Carolina Center for Jewish Studies in 2003, and has since increased its course offerings for undergraduate and graduate students interested in Jewish topics. Both Duke and UNC have drawn Jewish students and faculty through the development of Jewish Studies curricula.

The Late 20th Century

In 1977, local Jews formed the Durham-Chapel Hill Jewish Federation and Community Council, an umbrella group that brought together the area’s increasingly diverse Jewish community and helped to manage relationships between Jews and the broader population. In the 1980s and onwards, the presence of Israeli, South African, and Russian Jews, usually professionals employed on campuses or at the research park, spawned informal networks based on national origin. The two Durham synagogues were supplemented by the Chapel Hill Kehillah, a Reconstructionist congregation that formed in 1996 and has occupied a building near the UNC campus since 2001. In 1998, Chabad-Lubavitch established itself in the area, and continues to work on both the UNC and Duke campuses.

Judea Reform’s original land increased, and in 1995 became the site of the Lerner Jewish Community Day School. The cross-denominational elementary school serves children from each congregation, and a significant percentage of unaffiliated families. After a major fundraising effort, the temple and day school were joined by the seven million dollar Levin Jewish Community Center.

From the 1950s on, Jews at UNC and Duke grew simultaneously more comfortable outwardly identifying as Jews and less conspicuously divided from peers among the student body and faculty. The establishment of a Hillel House on the UNC campus in 1951 marked the accepted status of the Jewish organization. The university ended its practice of asking incoming students about religious preferences in 1955, information that previously allowed housing administration to lump Jewish students together in particular dormitories. In 1957, basketball star Lenny Rosenbluth improved the image of New York Jews on campus, leading the team to an NCAA championship and earning National Player of the Year honors. Some professional bias persisted at Duke University Schools of Medicine and Law, as well as other departments at both universities, until at least the 1960s. In the last decades of the 20th century, however, Jews were well represented in administrative posts at both institutions.

At Duke, Jewish enrollment has risen as a percent of the total population as the university has come to compete with the Ivy League for prestige, while UNC’s rising standards for out-of-state students contributed in the 1990s to a decrease in Jewish students as a percentage of the total population. In terms of real numbers, both campuses have seen an increase in Jewish enrollment, with a combined total of over 2,700 students. Recently, Duke has reinvigorated its Jewish Studies program, originally established in the early 1970s. UNC founded the Carolina Center for Jewish Studies in 2003, and has since increased its course offerings for undergraduate and graduate students interested in Jewish topics. Both Duke and UNC have drawn Jewish students and faculty through the development of Jewish Studies curricula.

The Late 20th Century

In 1977, local Jews formed the Durham-Chapel Hill Jewish Federation and Community Council, an umbrella group that brought together the area’s increasingly diverse Jewish community and helped to manage relationships between Jews and the broader population. In the 1980s and onwards, the presence of Israeli, South African, and Russian Jews, usually professionals employed on campuses or at the research park, spawned informal networks based on national origin. The two Durham synagogues were supplemented by the Chapel Hill Kehillah, a Reconstructionist congregation that formed in 1996 and has occupied a building near the UNC campus since 2001. In 1998, Chabad-Lubavitch established itself in the area, and continues to work on both the UNC and Duke campuses.

Judea Reform’s original land increased, and in 1995 became the site of the Lerner Jewish Community Day School. The cross-denominational elementary school serves children from each congregation, and a significant percentage of unaffiliated families. After a major fundraising effort, the temple and day school were joined by the seven million dollar Levin Jewish Community Center.

The Jewish Community in Durham and Chapel Hill Today

On a given Saturday, local Jews meet at each of the synagogues and kehillot, as well as in more informal and irregular groups, including Hillel and Chabad minyans, and meetings of a Chapel Hill Kehillah offshoot, Etz Chayim, that uses the UNC Hillel building. Singles and young families meet through events organized by Triangle Kesher. Duke and UNC host lectures that attract members of the campus community and are heavily attended by nearby Jewish retirees. In addition to at least two local klezmer bands, the Triangle Jewish Chorale and other groups play Jewish music for concerts, holidays, and lifecycle events. Other Jewish groups, including secular humanists, religious political radicals, and a Yiddish reading group maintain their own circles. The Triangle Jewish Film Festival, part of the Institute of Southern Jewish Life’s Jewish Cinema South program, takes place every fall.

In recent decades, Durham and Chapel Hill have emerged as diverse, vibrant, and growing Jewish communities in a region that has seen the decline of many other small town congregations. The key to their success has been the presence of UNC and Duke as well as the high-tech economy centered around the Triangle Research Park. For these reasons, the Durham/Chapel Hill Jewish community will likely flourish for years to come.

In recent decades, Durham and Chapel Hill have emerged as diverse, vibrant, and growing Jewish communities in a region that has seen the decline of many other small town congregations. The key to their success has been the presence of UNC and Duke as well as the high-tech economy centered around the Triangle Research Park. For these reasons, the Durham/Chapel Hill Jewish community will likely flourish for years to come.

Sources

Rogoff, Leonard. Homelands: Southern Jewish Identity in Durham and Chapel Hill, North Carolina.