Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Gastonia, North Carolina

Overview >> North Carolina >> Gastonia

Gastonia: Historical Overview

|

Gastonia, North Carolina, was a product of the New South. Incorporated in 1877, Gastonia was founded at the junction of two major railroads. It eventually became a regional manufacturing center, boasting eleven cotton mills by 1910. The following year, the town annexed the nearby Loray Mill, at one time the largest cotton mill in the South, and its surrounding residential areas. This annexation doubled the size of Gastonia, which became known as the “Combined Yarn Capital of the World.”

The Jewish community in Gastonia has existed since the turn of the 20th century, and continues today. |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Gastonia

David Lebovitz

If the railroad and cotton mills created Gastonia, then David Lebovitz created its Jewish community. Lebovitz was born in Lithuania in 1872. Determined to keep their son out of the Russian army, his parents sent him to America in 1887 when he was only 15. He first arrived in Baltimore and lived with one of his father’s friends for a year. At the time, there was widespread unemployment and Lebovitz was unable to find a good paying job, so he took the $8 he had saved and bought some merchandise to peddle. In 1891, he traveled through Gaston County, North Carolina. He was struck by Gastonia, with its growing cotton mills, and decided to settle in the town, opening a dry goods store in 1892.

By 1900, Lebovitz was a successful Gastonian merchant and married to Lena Schultz, a 24-year-old woman from Spartanburg, South Carolina. The two of them had six daughters, the oldest of which, Tena, born in 1901, was the first Jew born in Gastonia. After many of Lebovitz’s customers had trouble pronouncing his name, he decided to shorten it, changing the name of his business to “Lebo’s Department Store.”

The Community Grows

A number of other Jewish families moved to Gastonia just after the turn of the century. Harry and Lena Schneider and Moses and Harry Roman came around 1901. Herman and Charles Boraz arrived in 1905, and Alex, Louis, and Meyer Sherman reached Gastonia in 1907. By 1910, Maurice Silverstein and Isaac Garmise lived in town. The largest influx of Jews into Gastonia took place between 1915 and the mid-1920s. Among those Jews were: the Frank Goldberg family and his brothers, Robert, Max, Ben, and their families, the Harry Goldstein family, the John Honigman family, the Lou London family, the Ben Lieber family, the Abe Karesh family, the Emanuel Frohman family, the Jack Witten family, the Sam Sapperstein family, Moe Schultz, Sol Sturman, Maurice Honigman, and Sidney Levin. Most of these new arrivals were merchants, though several were involved with the growing textile industry. The Jewish community grew from 29 people in 1907 to 99 in 1927.

The Goldberg Family

The most prominent textile manufacturers in the Jewish community were the Goldberg family. Frank Goldberg was born in Latvia in 1879 and immigrated to the United States when he was in his twenties, settling initially in Atlanta, Georgia, where he reunited with and married his childhood sweetheart, Ida Sadie Paradies. They then moved to Columbia, South Carolina, where Frank went into the cotton waste business. In 1917, the Goldbergs moved to Gastonia where Frank bought his first textile mill in Bessemer City. Eventually, he had at least six factories. It was a family business with his sons, Cy, Sam, and Herbert, his brother Max, and his son-in-law Clarence Ross working at the various mills. When Frank Goldberg died in 1945, he left a generous bequest to the Gastonia synagogue which was used several years later to renovate the sanctuary. The local B’nai B’rith Lodge was renamed in his honor.

If the railroad and cotton mills created Gastonia, then David Lebovitz created its Jewish community. Lebovitz was born in Lithuania in 1872. Determined to keep their son out of the Russian army, his parents sent him to America in 1887 when he was only 15. He first arrived in Baltimore and lived with one of his father’s friends for a year. At the time, there was widespread unemployment and Lebovitz was unable to find a good paying job, so he took the $8 he had saved and bought some merchandise to peddle. In 1891, he traveled through Gaston County, North Carolina. He was struck by Gastonia, with its growing cotton mills, and decided to settle in the town, opening a dry goods store in 1892.

By 1900, Lebovitz was a successful Gastonian merchant and married to Lena Schultz, a 24-year-old woman from Spartanburg, South Carolina. The two of them had six daughters, the oldest of which, Tena, born in 1901, was the first Jew born in Gastonia. After many of Lebovitz’s customers had trouble pronouncing his name, he decided to shorten it, changing the name of his business to “Lebo’s Department Store.”

The Community Grows

A number of other Jewish families moved to Gastonia just after the turn of the century. Harry and Lena Schneider and Moses and Harry Roman came around 1901. Herman and Charles Boraz arrived in 1905, and Alex, Louis, and Meyer Sherman reached Gastonia in 1907. By 1910, Maurice Silverstein and Isaac Garmise lived in town. The largest influx of Jews into Gastonia took place between 1915 and the mid-1920s. Among those Jews were: the Frank Goldberg family and his brothers, Robert, Max, Ben, and their families, the Harry Goldstein family, the John Honigman family, the Lou London family, the Ben Lieber family, the Abe Karesh family, the Emanuel Frohman family, the Jack Witten family, the Sam Sapperstein family, Moe Schultz, Sol Sturman, Maurice Honigman, and Sidney Levin. Most of these new arrivals were merchants, though several were involved with the growing textile industry. The Jewish community grew from 29 people in 1907 to 99 in 1927.

The Goldberg Family

The most prominent textile manufacturers in the Jewish community were the Goldberg family. Frank Goldberg was born in Latvia in 1879 and immigrated to the United States when he was in his twenties, settling initially in Atlanta, Georgia, where he reunited with and married his childhood sweetheart, Ida Sadie Paradies. They then moved to Columbia, South Carolina, where Frank went into the cotton waste business. In 1917, the Goldbergs moved to Gastonia where Frank bought his first textile mill in Bessemer City. Eventually, he had at least six factories. It was a family business with his sons, Cy, Sam, and Herbert, his brother Max, and his son-in-law Clarence Ross working at the various mills. When Frank Goldberg died in 1945, he left a generous bequest to the Gastonia synagogue which was used several years later to renovate the sanctuary. The local B’nai B’rith Lodge was renamed in his honor.

Organized Jewish Life in Gastonia

Early on, the Jews of Gastonia would travel to Charlotte to attend services. Soon, Gastonia and the surrounding communities in Gaston, Lincoln, Cleveland, York, and Mecklenburg counties grew enough that Jews were able to hold regular services in people’s homes. By 1910, Gastonia Jews began to hold services in empty stores, halls, or any venue that would hold them. In 1927, for example, they held their Succoth celebration in the dining room of a local hotel. They also began to bring in Dr. Herman Boaz, an itinerant eyeglass peddler, to conduct Orthodox services for funerals and the High Holidays.

Around 1912, David Lebovitz and Harry Schneider, another successful Gastonian merchant, began to raise money to build a synagogue. The following year, the Hebrew Congregation of Gastonia was officially organized with David Lebovitz as the President, Alex Sherman as Vice-President, Harry Schneider as Treasurer, and Louis Sherman as Secretary. Frank Goldberg soon joined the congregation’s leadership, alternating the presidency with David Lebovitz for the next several years. Lebovitz, Gastonia’s first Jewish settler, had long dreamed of establishing a synagogue in the city, and even bought a Torah for the community, keeping it in an ark in his home library. He later gave the scroll to the Gastonia congregation.

During this early period, the congregation was strictly Orthodox. Rabbi Silverstein of Richmond, Virginia, an uncle of Maurice Silverstein, would come to Gastonia once in a while to lead services. Around 1918, the congregation, now numbering 39 members, hired its first full-time religious leader, Rabbi Stein, who also served as cantor, Hebrew teacher, and shochet (kosher butcher). Stein owned a kosher butcher shop in town to supplement the meager income which the small congregation could afford to pay. Despite having a rabbi, the congregation still met in people’s homes and rented rooms. In 1919, Hinda Lebovitz, the daughter of David and Lena, started a religious school for the congregation; she taught the classes herself in her parents’ home. Around the same time, Lena Lebovitz founded the congregation’s Sisterhood, serving as its president for 15 years. The group raised money for the congregation through rummage sales, dinners, and other events.

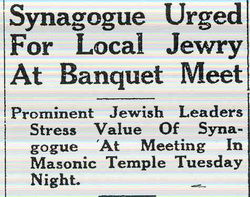

The only thing the growing congregation was missing was a synagogue. The group redoubled its efforts to raise money for a building in 1919. Each member was asked to make a significant donation to the cause. At one fundraising event, Frank Goldberg offered to match each contribution that was given. By 1925, they had hired an architect, Hugh White, to draw up plans for the building. Two years later, they bought land. In March 1928, Jewish leaders from around the state attended a banquet held at the Gastonia Masonic Temple. Gertrude Weil and rabbis from Charlotte and Greensboro spoke to the audience of Gastonia Jews, encouraging them to build a house of worship. Later that year, the synagogue construction began. During the last few months of 1928, the congregation of Gastonia experienced both tragedy and joy. On September 6, 1928, David Lebovitz passed away at the age of 56, before he could see his dream of a synagogue completed. Just weeks later, Abraham Garmise became the first bar mitzvah at the new synagogue. Since the sanctuary was not yet complete, the service was held in the basement. Construction was completed and Temple Emanuel officially opened its doors on January 1, 1929.

Unfortunately, Temple Emanuel was unable to escape the effects of the Great Depression, which hit Gastonia and its cotton mills especially hard. Due to the economic crisis, many of the members of the congregation could not afford to pay their dues. As a result, in 1933 the congregation had to let go its full-time rabbi, Lewis Feigon, who had led Temple Emanuel for the previous four years. Not too long after, the congregation was forced to close the synagogue due to a lack of operational funds; the building was only used for special events and the High Holidays. Members would hold regular services in private homes as they had done in the early years of the congregation.

During this dark period, Clarence Ross, who had married Frank and Sadie Goldberg’s daughter Ethel, became the congregation’s president in 1933. Under Ross’ energetic leadership, Temple Emanuel was reorganized and slowly got back on its financial feet. The congregation even purchased land for a cemetery. During Ross’ tenure, Temple Emanuel moved away from strict Orthodoxy and began its evolution towards Reform Judaism, though they continued to rely on lay readers to lead services. In 1940, the congregation reestablished its religious school, which for the first time met in the synagogue. Led by Mrs. Adolph Hahn, the school initially had over fifteen children. That same year, the Temple Emanuel Sisterhood became a Hadassah chapter as members worked to support both the congregation and the growing Jewish settlement in Palestine. By the early 1940s, a growing number of Jews settled in the Gastonia area, which helped establish a firm financial base for Temple Emanuel.

Around this time, the congregation decided to join the Reform movement. In 1943, they hired Rabbi William Silverman, who had been trained at Hebrew Union College. They also joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations. Temple Emanuel had 33 contributing members in 1945. Rabbi Silverman left Temple Emanuel in 1946 and was succeeded by William Sajowitz. Sajowitz stayed for eighteen months and was then replaced by Rabbi Jerome Mark, who stayed with the congregation until 1953. During Rabbi Mark’s tenure, the congregation held its first confirmation ceremony, with a class of two students. Later, the temple started a youth group chapter affiliated with the National Federation of Temple Youth.

Early on, the Jews of Gastonia would travel to Charlotte to attend services. Soon, Gastonia and the surrounding communities in Gaston, Lincoln, Cleveland, York, and Mecklenburg counties grew enough that Jews were able to hold regular services in people’s homes. By 1910, Gastonia Jews began to hold services in empty stores, halls, or any venue that would hold them. In 1927, for example, they held their Succoth celebration in the dining room of a local hotel. They also began to bring in Dr. Herman Boaz, an itinerant eyeglass peddler, to conduct Orthodox services for funerals and the High Holidays.

Around 1912, David Lebovitz and Harry Schneider, another successful Gastonian merchant, began to raise money to build a synagogue. The following year, the Hebrew Congregation of Gastonia was officially organized with David Lebovitz as the President, Alex Sherman as Vice-President, Harry Schneider as Treasurer, and Louis Sherman as Secretary. Frank Goldberg soon joined the congregation’s leadership, alternating the presidency with David Lebovitz for the next several years. Lebovitz, Gastonia’s first Jewish settler, had long dreamed of establishing a synagogue in the city, and even bought a Torah for the community, keeping it in an ark in his home library. He later gave the scroll to the Gastonia congregation.

During this early period, the congregation was strictly Orthodox. Rabbi Silverstein of Richmond, Virginia, an uncle of Maurice Silverstein, would come to Gastonia once in a while to lead services. Around 1918, the congregation, now numbering 39 members, hired its first full-time religious leader, Rabbi Stein, who also served as cantor, Hebrew teacher, and shochet (kosher butcher). Stein owned a kosher butcher shop in town to supplement the meager income which the small congregation could afford to pay. Despite having a rabbi, the congregation still met in people’s homes and rented rooms. In 1919, Hinda Lebovitz, the daughter of David and Lena, started a religious school for the congregation; she taught the classes herself in her parents’ home. Around the same time, Lena Lebovitz founded the congregation’s Sisterhood, serving as its president for 15 years. The group raised money for the congregation through rummage sales, dinners, and other events.

The only thing the growing congregation was missing was a synagogue. The group redoubled its efforts to raise money for a building in 1919. Each member was asked to make a significant donation to the cause. At one fundraising event, Frank Goldberg offered to match each contribution that was given. By 1925, they had hired an architect, Hugh White, to draw up plans for the building. Two years later, they bought land. In March 1928, Jewish leaders from around the state attended a banquet held at the Gastonia Masonic Temple. Gertrude Weil and rabbis from Charlotte and Greensboro spoke to the audience of Gastonia Jews, encouraging them to build a house of worship. Later that year, the synagogue construction began. During the last few months of 1928, the congregation of Gastonia experienced both tragedy and joy. On September 6, 1928, David Lebovitz passed away at the age of 56, before he could see his dream of a synagogue completed. Just weeks later, Abraham Garmise became the first bar mitzvah at the new synagogue. Since the sanctuary was not yet complete, the service was held in the basement. Construction was completed and Temple Emanuel officially opened its doors on January 1, 1929.

Unfortunately, Temple Emanuel was unable to escape the effects of the Great Depression, which hit Gastonia and its cotton mills especially hard. Due to the economic crisis, many of the members of the congregation could not afford to pay their dues. As a result, in 1933 the congregation had to let go its full-time rabbi, Lewis Feigon, who had led Temple Emanuel for the previous four years. Not too long after, the congregation was forced to close the synagogue due to a lack of operational funds; the building was only used for special events and the High Holidays. Members would hold regular services in private homes as they had done in the early years of the congregation.

During this dark period, Clarence Ross, who had married Frank and Sadie Goldberg’s daughter Ethel, became the congregation’s president in 1933. Under Ross’ energetic leadership, Temple Emanuel was reorganized and slowly got back on its financial feet. The congregation even purchased land for a cemetery. During Ross’ tenure, Temple Emanuel moved away from strict Orthodoxy and began its evolution towards Reform Judaism, though they continued to rely on lay readers to lead services. In 1940, the congregation reestablished its religious school, which for the first time met in the synagogue. Led by Mrs. Adolph Hahn, the school initially had over fifteen children. That same year, the Temple Emanuel Sisterhood became a Hadassah chapter as members worked to support both the congregation and the growing Jewish settlement in Palestine. By the early 1940s, a growing number of Jews settled in the Gastonia area, which helped establish a firm financial base for Temple Emanuel.

Around this time, the congregation decided to join the Reform movement. In 1943, they hired Rabbi William Silverman, who had been trained at Hebrew Union College. They also joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations. Temple Emanuel had 33 contributing members in 1945. Rabbi Silverman left Temple Emanuel in 1946 and was succeeded by William Sajowitz. Sajowitz stayed for eighteen months and was then replaced by Rabbi Jerome Mark, who stayed with the congregation until 1953. During Rabbi Mark’s tenure, the congregation held its first confirmation ceremony, with a class of two students. Later, the temple started a youth group chapter affiliated with the National Federation of Temple Youth.

Temple Emanuel

Temple Emanuel

Challenging Anti-Semitism in Gastonia

While Jews became an important part of Gastonia’s economy, they still faced occasional anti-Semitism. Brooklyn-born Marshall Rauch married Frank Goldberg’s daughter, Jeanie, after meeting at Duke University in Durham. Duke had a strict quota on Jewish students at the time, and non-Jewish fraternities and sororities did not welcome Jewish members. When Rauch and his wife tried to buy land for a house in Gastonia after World War II, the owner told them that he would not sell to Jews or Greeks. Jews were also excluded from various clubs in Gastonia, including the Eagle Club.

Combating this discrimination motivated Marshall Rauch to run for city council. Many of the Jews in town discouraged him from running, saying that he should not “rock the boat.” Nevertheless, he won the election and ended up spending three terms on the council before running for the state senate. Rauch had a long career in state government, serving 24 years in the North Carolina Senate, the first Jew ever to be elected to that office. Due to his influence, the Senate amended the rule banning hats on the floor or in the gallery to add an exception for rabbis and they stopped invoking Jesus’s name at the end of the morning invocation. With Rauch’s help, the state legislature and senate also passed a bill making Yom Kippur a state holiday in North Carolina so Jewish kids would not have to go to school and older Jews would be exempt from jury duty on that day. Rauch wasn’t the only Gastonia Jew to get involved in local politics; in 1955, Leon Schneider was elected mayor of Gastonia in a landslide.

In addition to his political career, Rauch became a very successful businessman. He started working for his father-in-law’s textile business. Eventually, Rauch started his own manufacturing business, Rauch Industries, in nearby Bessemer City, which made satin and glass Christmas ornaments. By 1990, the company was the largest manufacturer of satin and glass Christmas ornaments in the world.

The Community Grows

During the 1950s and 1960s, the Jewish community of Gastonia once again experienced significant growth. Temple Emanuel had grown to 50 contributing members by 1965. Five years later, the congregation had 76 members. Despite this growth, the congregation continued to face tragedy and challenges. In 1957 their new rabbi, Jerome Cohen, was killed in an automobile accident just before Rosh Hashanah. He had only been at Temple Emanuel for a month. Rabbi Joseph Utschen took over and stayed in Gastonia until 1961. In 1958, someone placed a suitcase full of dynamite on the front steps of the synagogue. Luckily, a police officer, who was passing by, noticed the unusual case and interceded just before the bomb exploded. This was just one of a string of temple bombings in the South at the time. After this near tragic incident, Temple Emanuel had special police protection during Friday night services and Sunday religious school.

Although Temple Emanuel was officially Reform, it still maintained various traditional practices. Until the 1970s, an Orthodox lay-led minyan met in the temple on the High Holidays. In 1974, the congregation stopped observing the second day of Rosh Hashanah. This trend toward Reform corresponded with Reform’s return to tradition; the increased Hebrew in the Reform movement’s 1975 prayer book Gates of Prayer was a nice fit for the traditionally rooted Gastonia congregation.

While Jews became an important part of Gastonia’s economy, they still faced occasional anti-Semitism. Brooklyn-born Marshall Rauch married Frank Goldberg’s daughter, Jeanie, after meeting at Duke University in Durham. Duke had a strict quota on Jewish students at the time, and non-Jewish fraternities and sororities did not welcome Jewish members. When Rauch and his wife tried to buy land for a house in Gastonia after World War II, the owner told them that he would not sell to Jews or Greeks. Jews were also excluded from various clubs in Gastonia, including the Eagle Club.

Combating this discrimination motivated Marshall Rauch to run for city council. Many of the Jews in town discouraged him from running, saying that he should not “rock the boat.” Nevertheless, he won the election and ended up spending three terms on the council before running for the state senate. Rauch had a long career in state government, serving 24 years in the North Carolina Senate, the first Jew ever to be elected to that office. Due to his influence, the Senate amended the rule banning hats on the floor or in the gallery to add an exception for rabbis and they stopped invoking Jesus’s name at the end of the morning invocation. With Rauch’s help, the state legislature and senate also passed a bill making Yom Kippur a state holiday in North Carolina so Jewish kids would not have to go to school and older Jews would be exempt from jury duty on that day. Rauch wasn’t the only Gastonia Jew to get involved in local politics; in 1955, Leon Schneider was elected mayor of Gastonia in a landslide.

In addition to his political career, Rauch became a very successful businessman. He started working for his father-in-law’s textile business. Eventually, Rauch started his own manufacturing business, Rauch Industries, in nearby Bessemer City, which made satin and glass Christmas ornaments. By 1990, the company was the largest manufacturer of satin and glass Christmas ornaments in the world.

The Community Grows

During the 1950s and 1960s, the Jewish community of Gastonia once again experienced significant growth. Temple Emanuel had grown to 50 contributing members by 1965. Five years later, the congregation had 76 members. Despite this growth, the congregation continued to face tragedy and challenges. In 1957 their new rabbi, Jerome Cohen, was killed in an automobile accident just before Rosh Hashanah. He had only been at Temple Emanuel for a month. Rabbi Joseph Utschen took over and stayed in Gastonia until 1961. In 1958, someone placed a suitcase full of dynamite on the front steps of the synagogue. Luckily, a police officer, who was passing by, noticed the unusual case and interceded just before the bomb exploded. This was just one of a string of temple bombings in the South at the time. After this near tragic incident, Temple Emanuel had special police protection during Friday night services and Sunday religious school.

Although Temple Emanuel was officially Reform, it still maintained various traditional practices. Until the 1970s, an Orthodox lay-led minyan met in the temple on the High Holidays. In 1974, the congregation stopped observing the second day of Rosh Hashanah. This trend toward Reform corresponded with Reform’s return to tradition; the increased Hebrew in the Reform movement’s 1975 prayer book Gates of Prayer was a nice fit for the traditionally rooted Gastonia congregation.

The Jewish Community in Gastonia Today

Despite the relatively small size of the congregation, Temple Emanuel continued to employ full-time rabbis in the 1970s and 1980s, though most stayed only a short time. In recent years, the congregation has not had a full-time rabbi. The Rauch Temple Emanuel Endowment Fund, started with a $250,000 gift from the Rauch family, has helped maintain the financial health of the congregation.

In contrast to many other small Southern Jewish communities, Gastonia has maintained its vitality in recent decades. In 2010, Temple Emanuel was a vibrant congregation with 72 member families, a religious school, weekly Shabbat services and adult education classes, and an active Sisterhood.

In contrast to many other small Southern Jewish communities, Gastonia has maintained its vitality in recent decades. In 2010, Temple Emanuel was a vibrant congregation with 72 member families, a religious school, weekly Shabbat services and adult education classes, and an active Sisterhood.