Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Greensboro, North Carolina

Overview >> North Carolina >> Greensboro

Greensboro: Historical Overview

|

The end of the 19th century was a period of immense change in the United States and North Carolina. With industrialization at full thrust, the era witnessed social transformations that reshaped predominantly rural America. It was a period of population shifts, with people moving from the countryside to cities, from state to state and from the Old World to the New World.

The embodiment of these developments is a mansion of 13,000 square feet, boasting 23 rooms and at one point 23,000 apple trees divided between four orchards. This is Flat Top Manor, the home of textile industrialist, conservationist, and philanthropist Moses Cone. The estate is a telling illustration of Jewish life and history in the budding metropolis of Greensboro, North Carolina. Cone, along with his partner and brother Ceasar, were amongst the first Jews to arrive in Greensboro in the 1890s. Over a century later, these pioneer Jewish families – of which the Cones are just one example – have left a legacy of community and religious engagement that have sustained Jewish life in the city. |

Though the Jewish presence in Greensboro only began in the years leading into the 20th century, the soil in which Jews would become rooted was made fertile by several developments of centuries before. The town gained its name from Revolutionary War hero Nathanael Greene who, while losing the Battle of Guilford Court House, inflicted heavy casualties on British troops. In 1808, Greensboro was incorporated as the seat of Guilford County. Being a low point of the Blue Ridge Mountains, the town began as thick forest covered by water and was purchased for $98. By 1829, Greensboro had a population of almost 500, including 101 slaves and 26 free blacks.

From its humble origins, Greensboro’s post-Civil War growth was hastened by several crucial antebellum developments that had significant ramifications for its future Jewish population. In 1828, Henry Humphreys began operation of a steam-powered cotton mill, the first in North Carolina. Just five years later, 75 looms were producing cotton textiles that were sold in the state and exported across state lines. As a result, Greensboro became a pioneer city of textile production in the South. The completion of the North Carolina Railroad through Greensboro in 1856 was another crucial development that would later facilitate the city’s industrialization. The railroad benefited Greensboro’s economy bringing in not just new wealth but new inhabitants. The railroad was a primary motivation for the placement of textile manufacturing plants in the city and surrounding environs. Greensboro’s pre-war development allowed the city to flourish as an industrial center during the New South era. By 1891, there were 16 major production plants within the city.

Greensboro also benefited from a relatively diverse group of original American settlers. Significant to the later Jewish population was its early Quaker community. With a tradition of social cooperation, opposition to slavery, religious tolerance and overall progressive worldview, Quakers contributed to an open, congenial environment in early Greensboro. Throughout the antebellum period, Greensboro was a major stop on the Underground Railroad. Along with the population of Presbyterians and Methodists, Quakers helped make Greensboro one of the more tolerant places in the South, a tradition that played an important role in attracting its first Jewish residents.

From its humble origins, Greensboro’s post-Civil War growth was hastened by several crucial antebellum developments that had significant ramifications for its future Jewish population. In 1828, Henry Humphreys began operation of a steam-powered cotton mill, the first in North Carolina. Just five years later, 75 looms were producing cotton textiles that were sold in the state and exported across state lines. As a result, Greensboro became a pioneer city of textile production in the South. The completion of the North Carolina Railroad through Greensboro in 1856 was another crucial development that would later facilitate the city’s industrialization. The railroad benefited Greensboro’s economy bringing in not just new wealth but new inhabitants. The railroad was a primary motivation for the placement of textile manufacturing plants in the city and surrounding environs. Greensboro’s pre-war development allowed the city to flourish as an industrial center during the New South era. By 1891, there were 16 major production plants within the city.

Greensboro also benefited from a relatively diverse group of original American settlers. Significant to the later Jewish population was its early Quaker community. With a tradition of social cooperation, opposition to slavery, religious tolerance and overall progressive worldview, Quakers contributed to an open, congenial environment in early Greensboro. Throughout the antebellum period, Greensboro was a major stop on the Underground Railroad. Along with the population of Presbyterians and Methodists, Quakers helped make Greensboro one of the more tolerant places in the South, a tradition that played an important role in attracting its first Jewish residents.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Greensboro

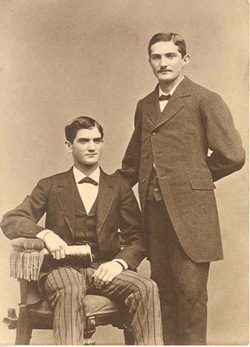

Moses & Ceasar Cone

Moses & Ceasar Cone

Early Jewish Settlers

There is some evidence of a Jewish presence in Greensboro prior to the Civil War. As early as February 1853, issues of the Greensboro Patriot had advertisements for Einstein & Co., a small retail store. Fellow Jewish store owners of this period included Morris Pretzfelder and Ephraim Fishblate, and later Isaac Isaacson and Simon Schiffman. Many were immigrants from major cities like New York and Baltimore. By the early 20th century, a growing number of Jews settled in Greensboro. Charles Weill came in 1911 after graduating from the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill; he was attracted to the city because it had recently chartered UNC-Greensboro. Max Edward Block immigrated from Beldograde, Russia, to Greensboro around 1901, and worked for the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company. Both Block and Weill would play important roles in the future of Greensboro’s Jewish life, but according to an official history of Temple Emanuel, “no single Jewish family has had more of an impact on the growth and development of Greensboro than that of the Cone family.”

Born into a German-Jewish immigrant family in Jonesborough, Tennessee, in 1857, Moses and Ceasar Cone were practically raised in the business world. By their teens, Moses and Ceasar worked as traveling salesmen for their father’s textile company, H. Cone and Sons. Beginning in the late 1880s, the brothers invested in cotton plaid production in Asheville, North Carolina. In 1891, they chartered the Cone Export and Commission Company; four years later the company established the Proximity Cotton Mills in Greensboro. According to a long-time resident of Greensboro, the Cone brothers chose this city because “Winston-Salem and Charlotte gave the Cone Brothers a feeling of hostility caused by anti-Semitism.” In 1902, the White Oak Cotton Mill opened as the world’s largest maker of denim products. As these factories took off, the Cones were in correspondence with another entrepreneurial pair of brothers, the Sternbergers. Managing a store in Clio, South Carolina, Herman and Emanuel were convinced by Moses Cone to move to Greensboro and establish the Revolution Cotton Mill. By 1910, the city’s population rose to nearly 16,000 as the Cones and Sternbergers became the industrial titans of Greensboro.

Leading industrialists like the Cones and Sternbergers often served a paternal role in these manufacturing towns, both to their workers and their overall community. For example, the rapidly expanding mills of Greensboro evolved into “an entire social support network unto itself.” According to the granddaughter of Herman Sternberger, the Greensboro mill village offered its residents “a school system, a welfare system, a physician, dentists, nurses, stores a YMCA and various charities. The company built houses and charged $4.00 per room and supported churches of the workers.” In addition to managing and supporting the livelihoods of their workers, the Cone and Sternberger brothers contributed to the cultural and social growth of Greensboro. Today, Greensboro’s major hospital bears the name of Moses Cone, as does Cone Elementary School and the Cone Ballroom at UNC-Greensboro. Local art galleries and numerous charities have also been the beneficiaries of these two prominent families.

There is some evidence of a Jewish presence in Greensboro prior to the Civil War. As early as February 1853, issues of the Greensboro Patriot had advertisements for Einstein & Co., a small retail store. Fellow Jewish store owners of this period included Morris Pretzfelder and Ephraim Fishblate, and later Isaac Isaacson and Simon Schiffman. Many were immigrants from major cities like New York and Baltimore. By the early 20th century, a growing number of Jews settled in Greensboro. Charles Weill came in 1911 after graduating from the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill; he was attracted to the city because it had recently chartered UNC-Greensboro. Max Edward Block immigrated from Beldograde, Russia, to Greensboro around 1901, and worked for the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company. Both Block and Weill would play important roles in the future of Greensboro’s Jewish life, but according to an official history of Temple Emanuel, “no single Jewish family has had more of an impact on the growth and development of Greensboro than that of the Cone family.”

Born into a German-Jewish immigrant family in Jonesborough, Tennessee, in 1857, Moses and Ceasar Cone were practically raised in the business world. By their teens, Moses and Ceasar worked as traveling salesmen for their father’s textile company, H. Cone and Sons. Beginning in the late 1880s, the brothers invested in cotton plaid production in Asheville, North Carolina. In 1891, they chartered the Cone Export and Commission Company; four years later the company established the Proximity Cotton Mills in Greensboro. According to a long-time resident of Greensboro, the Cone brothers chose this city because “Winston-Salem and Charlotte gave the Cone Brothers a feeling of hostility caused by anti-Semitism.” In 1902, the White Oak Cotton Mill opened as the world’s largest maker of denim products. As these factories took off, the Cones were in correspondence with another entrepreneurial pair of brothers, the Sternbergers. Managing a store in Clio, South Carolina, Herman and Emanuel were convinced by Moses Cone to move to Greensboro and establish the Revolution Cotton Mill. By 1910, the city’s population rose to nearly 16,000 as the Cones and Sternbergers became the industrial titans of Greensboro.

Leading industrialists like the Cones and Sternbergers often served a paternal role in these manufacturing towns, both to their workers and their overall community. For example, the rapidly expanding mills of Greensboro evolved into “an entire social support network unto itself.” According to the granddaughter of Herman Sternberger, the Greensboro mill village offered its residents “a school system, a welfare system, a physician, dentists, nurses, stores a YMCA and various charities. The company built houses and charged $4.00 per room and supported churches of the workers.” In addition to managing and supporting the livelihoods of their workers, the Cone and Sternberger brothers contributed to the cultural and social growth of Greensboro. Today, Greensboro’s major hospital bears the name of Moses Cone, as does Cone Elementary School and the Cone Ballroom at UNC-Greensboro. Local art galleries and numerous charities have also been the beneficiaries of these two prominent families.

Proximity Cotton Mill

Proximity Cotton Mill

Civic Engagement

The civic engagement of the Jewish community in the early 20th century was impressive and much was energized by the distinction of its entrepreneurial leaders. Ceasar Cone was president of the Chamber of Commerce, while his wife Jeanette Siegel Cone and his son Ceasar Cone II served as leaders in several civic organizations. Emanuel Sternberger was the head of the Carolina Motor Club for North and South Carolina and the Greensboro Rotary while his wife, Bertha Strauss Sternberger, helped establish Greensboro’s park system and contributed to many charitable causes. Ceasar Cone II donated $50,000 for the construction of a YMCA for Greensboro’s black community. Such acts demonstrate the crucial role Jews played for all people living in Greensboro. Their commitment to improve Greensboro did not always spill over into their mills, which often relied on child labor, 10 hour work days, and denial of unionization rights.

The civic engagement of the Jewish community in the early 20th century was impressive and much was energized by the distinction of its entrepreneurial leaders. Ceasar Cone was president of the Chamber of Commerce, while his wife Jeanette Siegel Cone and his son Ceasar Cone II served as leaders in several civic organizations. Emanuel Sternberger was the head of the Carolina Motor Club for North and South Carolina and the Greensboro Rotary while his wife, Bertha Strauss Sternberger, helped establish Greensboro’s park system and contributed to many charitable causes. Ceasar Cone II donated $50,000 for the construction of a YMCA for Greensboro’s black community. Such acts demonstrate the crucial role Jews played for all people living in Greensboro. Their commitment to improve Greensboro did not always spill over into their mills, which often relied on child labor, 10 hour work days, and denial of unionization rights.

Greensboro Hebrew Congregation

Greensboro Hebrew Congregation

Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler

Organized Jewish Life in Greensboro

The fact that the two leading families of Greensboro’s modernization were Jewish not only established Jews at the top of the city’s power structure, but also ensured a steady stream of resources to support Jewish spiritual and cultural life. Yet by the early years of the 20th century, Greensboro still lacked a synagogue. The earliest known services took place on the second floor of the grocery store on South Elm Street. A documented Rosh Hashanah service took place in 1907, arranged by the Sternberger family. Sunday school classes also began that year, taking place in the homes of Ceasar Cone and the Schiffman brothers. These informal institutions were strikingly incongruous with the prominent status of Jews in Greensboro. In February of 1908, an official meeting of a board of trustees met to organize a temple for the city. Among the council were important businessmen; Emanuel and Herman Sternberger, jewelry merchant Augustus Schiffman, wholesale retailer Isaac Isaacson, and insurance salesman Max E. Block. They agreed to purchase the Friends Church for $2,500.

What made the purchase remarkable was that it was jointly funded by both Reform and Orthodox Jews. The Hebrew Congregation, its original name, impressively managed to satisfy both its Reform and Orthodox contingents in its early years. Two years after the purchase of the temple, a Jewish burial plot was obtained for $850. In 1914, the temple became affiliated with the Reform Union of American Hebrew Congregations, which alienated some of its Orthodox members, who began to worship separately within the synagogue. Nevertheless, the congregation secured the services of a shochet for a while to provide kosher meat to traditional members. The Jewish community also established the Greensboro Hebrew Aid Society to assist poor Jews, as well as relief funds for Jews in Palestine. As early as 1923, The Hebrew Congregation became one of the first synagogues to grant equal status to female members. Prominent women of the temple established vital services to congregants such as libraries, day care centers, programs for the elderly and mentally disabled and art tutorials.

The fact that the two leading families of Greensboro’s modernization were Jewish not only established Jews at the top of the city’s power structure, but also ensured a steady stream of resources to support Jewish spiritual and cultural life. Yet by the early years of the 20th century, Greensboro still lacked a synagogue. The earliest known services took place on the second floor of the grocery store on South Elm Street. A documented Rosh Hashanah service took place in 1907, arranged by the Sternberger family. Sunday school classes also began that year, taking place in the homes of Ceasar Cone and the Schiffman brothers. These informal institutions were strikingly incongruous with the prominent status of Jews in Greensboro. In February of 1908, an official meeting of a board of trustees met to organize a temple for the city. Among the council were important businessmen; Emanuel and Herman Sternberger, jewelry merchant Augustus Schiffman, wholesale retailer Isaac Isaacson, and insurance salesman Max E. Block. They agreed to purchase the Friends Church for $2,500.

What made the purchase remarkable was that it was jointly funded by both Reform and Orthodox Jews. The Hebrew Congregation, its original name, impressively managed to satisfy both its Reform and Orthodox contingents in its early years. Two years after the purchase of the temple, a Jewish burial plot was obtained for $850. In 1914, the temple became affiliated with the Reform Union of American Hebrew Congregations, which alienated some of its Orthodox members, who began to worship separately within the synagogue. Nevertheless, the congregation secured the services of a shochet for a while to provide kosher meat to traditional members. The Jewish community also established the Greensboro Hebrew Aid Society to assist poor Jews, as well as relief funds for Jews in Palestine. As early as 1923, The Hebrew Congregation became one of the first synagogues to grant equal status to female members. Prominent women of the temple established vital services to congregants such as libraries, day care centers, programs for the elderly and mentally disabled and art tutorials.

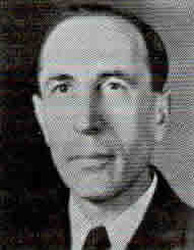

Rabbi Fred Rypins

Rabbi Fred Rypins

The Jewish population continued to grow in the interwar period. While in 1909 there were around 100 Jews in Greensboro, there were 400 by 1927. In 1922, The Hebrew Congregation began construction of a new synagogue. The Cone and Sternberger families, with their usual largesse, contributed $75,000. Noted architect Hobart Upjohn was commissioned for the new temple and his work so impressed the local Methodist Church that they hired him to design their new house of worship. The synagogue on Greene Street was a culmination of the congregation’s commitment to Jewish life in Greensboro, as each member contributed what they could. Emanuel Sternberger donated a new Torah, the Benjamin family purchased menorah lights, and at the suggestion of the Stern family an organ was purchased for $12,000. The building was in use by 1924 and a dedication ceremony was held on June 5th, 1925. By this time, the congregation had grown to 75 families. The temple on Greene Street was a worthy testament to the prominence of Greensboro’s Jewish community. The congregation continued to serve as a house of worship for both Reform and Orthodox Jews, albeit with separate services. Nevertheless, the congregation was Reform, with its main services primarily in English and the confirmation ceremony rather than the bar mitzvah.

Despite the challenges of the Great Depression, the congregation hired Rabbi Fred Rypins in 1931. A World War I veteran, Rabbi Rypins was a highly educated clergyman with a deep commitment to social justice. Rypins oversaw much of the charitable work of The Hebrew Congregation during the Depression. Lay members also took initiative in providing aid, such as Sam Goldman who secured food and financial assistance to the homeless who gathered near his store. While anti-Semitism rose around the country during the Depression, there was little evidence of this in Greensboro. Rabbi Rypins was granted free membership at the Greensboro Country Club and made President of the Greensboro’s Ministerial Association in 1938.

Despite the challenges of the Great Depression, the congregation hired Rabbi Fred Rypins in 1931. A World War I veteran, Rabbi Rypins was a highly educated clergyman with a deep commitment to social justice. Rypins oversaw much of the charitable work of The Hebrew Congregation during the Depression. Lay members also took initiative in providing aid, such as Sam Goldman who secured food and financial assistance to the homeless who gathered near his store. While anti-Semitism rose around the country during the Depression, there was little evidence of this in Greensboro. Rabbi Rypins was granted free membership at the Greensboro Country Club and made President of the Greensboro’s Ministerial Association in 1938.

Max Block

Max Block

Jewish Occupations

During the 1930s, several Greensboro Jews continued to own retail stores. These included Harry Chandgie’s hat store, Ben Marks’s shoe store and the local kosher delicatessen. A growing number of Jewish professionals settled in Greensboro. Maurice LeBauer became Greensboro’s first Jewish surgeon in 1931. Fellow physicians Jack Tannenbaum, Arthur Freedman and Edgar Marks arrived shortly after. A number of Jewish lawyers, including Charles Roth, Herbert Falk, Sidney Stern, Henry Isaacson, Norman Block, and A. Sol Weinstein practiced in the city. Many of these Jewish professional were emblematic of the first and second generation Jews who became fully assimilated into life in America and Greensboro during the first half of the 20th century.

World War II

During the 1930s, Greensboro Jews were concerned over the fate of Europe’s Jews. Rabbi Rypins’ sermons throughout the decade increasingly focused on Nazi repression of Jews. They raised funds for the American-Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, the American Palestine Campaign, and the Anti-Defamation League to assist German Jewish refugees. By October of 1934, the congregation had raised $9,500 for charitable causes, $7,000 of which was designated to the relief for German Jews.

The coming of World War II brought even greater demands and responses from the congregation. In the mobilization for war in the early 1940s, the U.S. Army opened Basic Training Camp 10 in Greensboro, stationing a multitude of soldiers in the city. The Jewish community welcomed the troops, especially the Jewish GIs. Jewish troops were invited over for meals at congregant’s homes and the temple’s basement was transformed into a social hall for the soldiers. Much of this was the work of lay people, notably Al and Min Klein, Nathan Markowitz, and Della Freed. Temple minutes reveal that synagogue activities focused on the war effort. In one meeting it was reported that the Greensboro Council and Sisterhood had sold $47,500 in war bonds. The manufacturing energy of the Cone Mills was reoriented for war production. Some members of the Greensboro Jewish community gave the ultimate sacrifice as members of the military. Of the 59 Greensboro Jews who served in the military, five perished: Robert Backer, Sanford Friedman, Ted Myers and Sigmund Selig Pearl.

After the war, a handful of refugees and Holocaust survivors settled in Greenboro. Walter Falk fled Karlruhe, Germany in the late 1930s, though sadly lost his mother. Otto Guttmann also managed to escape Germany through the British Refugee Committee’s Kindertransport effort in which young Jews from Germany and Austria were rescued during the Nazi regime. Harry Sloan fled Germany with his sister Alice and her husband Otto Loeb in 1938, just prior to Kristallnacht. Hank Brodt survived five different concentration camps and, after more than 60 years of separation from his brother Symcha, located his family in Israel and visited them in 2007. These survivors added invaluable stories and wisdom to the Greensboro Jewish community. In 1985, Temple Emanuel purchased Torah scrolls from Prostejov, Czechoslovakia, that had survived the Holocaust.

During the 1930s, several Greensboro Jews continued to own retail stores. These included Harry Chandgie’s hat store, Ben Marks’s shoe store and the local kosher delicatessen. A growing number of Jewish professionals settled in Greensboro. Maurice LeBauer became Greensboro’s first Jewish surgeon in 1931. Fellow physicians Jack Tannenbaum, Arthur Freedman and Edgar Marks arrived shortly after. A number of Jewish lawyers, including Charles Roth, Herbert Falk, Sidney Stern, Henry Isaacson, Norman Block, and A. Sol Weinstein practiced in the city. Many of these Jewish professional were emblematic of the first and second generation Jews who became fully assimilated into life in America and Greensboro during the first half of the 20th century.

World War II

During the 1930s, Greensboro Jews were concerned over the fate of Europe’s Jews. Rabbi Rypins’ sermons throughout the decade increasingly focused on Nazi repression of Jews. They raised funds for the American-Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, the American Palestine Campaign, and the Anti-Defamation League to assist German Jewish refugees. By October of 1934, the congregation had raised $9,500 for charitable causes, $7,000 of which was designated to the relief for German Jews.

The coming of World War II brought even greater demands and responses from the congregation. In the mobilization for war in the early 1940s, the U.S. Army opened Basic Training Camp 10 in Greensboro, stationing a multitude of soldiers in the city. The Jewish community welcomed the troops, especially the Jewish GIs. Jewish troops were invited over for meals at congregant’s homes and the temple’s basement was transformed into a social hall for the soldiers. Much of this was the work of lay people, notably Al and Min Klein, Nathan Markowitz, and Della Freed. Temple minutes reveal that synagogue activities focused on the war effort. In one meeting it was reported that the Greensboro Council and Sisterhood had sold $47,500 in war bonds. The manufacturing energy of the Cone Mills was reoriented for war production. Some members of the Greensboro Jewish community gave the ultimate sacrifice as members of the military. Of the 59 Greensboro Jews who served in the military, five perished: Robert Backer, Sanford Friedman, Ted Myers and Sigmund Selig Pearl.

After the war, a handful of refugees and Holocaust survivors settled in Greenboro. Walter Falk fled Karlruhe, Germany in the late 1930s, though sadly lost his mother. Otto Guttmann also managed to escape Germany through the British Refugee Committee’s Kindertransport effort in which young Jews from Germany and Austria were rescued during the Nazi regime. Harry Sloan fled Germany with his sister Alice and her husband Otto Loeb in 1938, just prior to Kristallnacht. Hank Brodt survived five different concentration camps and, after more than 60 years of separation from his brother Symcha, located his family in Israel and visited them in 2007. These survivors added invaluable stories and wisdom to the Greensboro Jewish community. In 1985, Temple Emanuel purchased Torah scrolls from Prostejov, Czechoslovakia, that had survived the Holocaust.

Moses Cone Memorial Hospital

Moses Cone Memorial Hospital

The Community Grows

After World War II, both Greensboro and its Jewish community enjoyed a remarkable growth spurt. Greensboro grew from 59,319 residents in 1940 to 144,076 in 1970. The Jewish community more than tripled in size, increasing from 500 in 1947 to 1,750 by 1968. While Cone Mills had become the largest denim manufacturer in the world, new commercial activity such as Lorillard Tobacco, Western Electric and the Moses H. Cone Hospital drew new Jewish arrivals. Greensboro Jews shared in this age of prosperity. The confidence of this period also incurred a sense of responsibility to fellow Jews worldwide, especially in the new state of Israel. Aid from Greensboro’s Jewish community continued to support Jewish refugees and displaced persons following the end of the war. Additionally, a remarkable $400,000 was raised between 1947 and 1949 for aid to Israel. Greensboro Jews have continued to support Israel ever since.

Greensboro’s growing maturity as a Jewish community meant that one congregation could no longer contain both Reform and traditional factions. In 1944 a group broke off from the Greensboro Hebrew Congregation to found Beth David, which affiliated with the Conservative movement. The Greensboro Hebrew Congregation, no longer representing the entire Jewish community, decided to change its name in 1949 to Temple Emanuel, in honor of its longtime leader Emanuel Sternberger. Despite this split, Temple Emanuel’s membership grew 50% between 1945 and 1962, when it reported 212 members. Much of this growth was due to the influx of Northern-born Jews. By the early 1960s, about half of Temple Emanuel's members were raised outside of the South, while an estimated 90% of Beth David's membership were Northern transplants.

After World War II, both Greensboro and its Jewish community enjoyed a remarkable growth spurt. Greensboro grew from 59,319 residents in 1940 to 144,076 in 1970. The Jewish community more than tripled in size, increasing from 500 in 1947 to 1,750 by 1968. While Cone Mills had become the largest denim manufacturer in the world, new commercial activity such as Lorillard Tobacco, Western Electric and the Moses H. Cone Hospital drew new Jewish arrivals. Greensboro Jews shared in this age of prosperity. The confidence of this period also incurred a sense of responsibility to fellow Jews worldwide, especially in the new state of Israel. Aid from Greensboro’s Jewish community continued to support Jewish refugees and displaced persons following the end of the war. Additionally, a remarkable $400,000 was raised between 1947 and 1949 for aid to Israel. Greensboro Jews have continued to support Israel ever since.

Greensboro’s growing maturity as a Jewish community meant that one congregation could no longer contain both Reform and traditional factions. In 1944 a group broke off from the Greensboro Hebrew Congregation to found Beth David, which affiliated with the Conservative movement. The Greensboro Hebrew Congregation, no longer representing the entire Jewish community, decided to change its name in 1949 to Temple Emanuel, in honor of its longtime leader Emanuel Sternberger. Despite this split, Temple Emanuel’s membership grew 50% between 1945 and 1962, when it reported 212 members. Much of this growth was due to the influx of Northern-born Jews. By the early 1960s, about half of Temple Emanuel's members were raised outside of the South, while an estimated 90% of Beth David's membership were Northern transplants.

The Civil Rights Era

Greensboro Jews were swept up in the civil rights movement, which achieved one its early victories in Greensboro. In 1960, four black students at North Carolina A&T University sat in the all-white section of a local Woolworths, the movement’s first sit-in protest. From that point on, the city had to confront segregation, provoking bitter division between supporters and detractors of the civil rights movement. Rabbi Rypins was both vocal and active in support of the movement as was his immediate successor Rabbi Joseph Asher. According to a history of Temple Emanuel, “Rabbi Asher was an outspoken advocate of equal rights in the community, and members of Temple Emanuel, without exception, supported an end to policies that characterized the Jim Crow South.” Congregant Neil Belenky was a freedom rider. Support for these causes sometimes worked to the detriment of Jewish locals. Leonard Guyes, a women’s apparel store owner who had hired blacks on an equal basis as whites, describes how business “just dried up” as white racists boycotted the store. These consequences highlight the courage of Greensboro’s Jews in supporting racial equality.

Greensboro Jews were swept up in the civil rights movement, which achieved one its early victories in Greensboro. In 1960, four black students at North Carolina A&T University sat in the all-white section of a local Woolworths, the movement’s first sit-in protest. From that point on, the city had to confront segregation, provoking bitter division between supporters and detractors of the civil rights movement. Rabbi Rypins was both vocal and active in support of the movement as was his immediate successor Rabbi Joseph Asher. According to a history of Temple Emanuel, “Rabbi Asher was an outspoken advocate of equal rights in the community, and members of Temple Emanuel, without exception, supported an end to policies that characterized the Jim Crow South.” Congregant Neil Belenky was a freedom rider. Support for these causes sometimes worked to the detriment of Jewish locals. Leonard Guyes, a women’s apparel store owner who had hired blacks on an equal basis as whites, describes how business “just dried up” as white racists boycotted the store. These consequences highlight the courage of Greensboro’s Jews in supporting racial equality.

The Jewish Community in Greensboro Today

Temple Emanuel's new building

Temple Emanuel's new building

Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler

While being a turbulent period, the 1960s was also one of growth for the city and its Jewish community. Economic development was abetted by massive urban redevelopment during the 1960s and 1970s. Though these transformations erased much of the city’s historic character, it laid the path for new industries to set up in Greensboro, such as banking and high tech firms.Along with these changes, the Jewish population boomed, growing from 1,750 people in 1968 to 3,000 in 1984. The community’s institutions flourished as well. Temple Emanuel expanded in 1998, purchasing land on Jefferson Road in northeast Greensboro for a second synagogue. Temple Emanuel maintained its old site as well, holding periodic services and special programs there. In 2007, the temple’s 550 member families celebrated the congregation’s 100th anniversary. Beth David built a new synagogue on Winview Terrace, and opened the B’nai Shalom Day School, which teaches children through the 8th grade.

In 1999, Maurice and Zmira Sabbah, who wanted to create a Jewish high school in Greensboro, purchased land for the construction of the nation’s first “Jewish pluralistic college prep boarding school.” The American Hebrew Academy opened its doors in 2001 and ever since has brought Jewish students to Greensboro to study in this pioneering institution.

When Jews arrived in Greensboro in the tumultuous industrial age, their presence was marked by smokestacks, twelve hour work days, and rumbling factories. From these economic roots sprung art, philanthropy, education and a vibrant spiritual existence that continues to define Greensboro’s Jewish community today.

In 1999, Maurice and Zmira Sabbah, who wanted to create a Jewish high school in Greensboro, purchased land for the construction of the nation’s first “Jewish pluralistic college prep boarding school.” The American Hebrew Academy opened its doors in 2001 and ever since has brought Jewish students to Greensboro to study in this pioneering institution.

When Jews arrived in Greensboro in the tumultuous industrial age, their presence was marked by smokestacks, twelve hour work days, and rumbling factories. From these economic roots sprung art, philanthropy, education and a vibrant spiritual existence that continues to define Greensboro’s Jewish community today.