Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Hickory, North Carolina

Overview >> North Carolina >> Hickory

Hickory: Historical Overview

|

The city of Hickory, North Carolina, got its start as a saloon. In the 1850s, Hickory Tavern opened for business in a dense forest to serve frontier travelers in western Carolina. Named for a large hickory tree just outside the front door of the log cabin structure, Hickory Tavern became a stop on the stagecoach line, as men and their horses would stop by for refreshment. A small settlement developed around the tavern after the Western North Carolina Railroad was built through the area in 1860. During the Civil War, the Confederate government built a commissary in the town, though they burned it in 1865 to keep it from falling into Union hands. While Hickory struggled during the years just after the war, it eventually began to flourish as a railroad center in 1870s. By 1876, 1500 people lived in the west Carolina boomtown. Among these settlers were a small number of Jews. From small beginnings, they would form a Jewish community that lasts today.

|

Stories of the Jewish Community in Hickory

Early Settlers

The first Jew to settle in Hickory was Lewis Elias, a merchant who moved to town from Statesville in 1861. Elias was one of the signers of the Hickory Tavern charter that officially incorporated the town in 1863. Elias did not remain in Hickory for very long, and had moved back to Statesville by 1870. In 1871, brothers-in-law Henry Scott and Julius Lowenstein, both of whom were German immigrants, opened a store in Hickory. Lowenstein was also a dentist, the first to settle in Hickory. Apparently, he plied both trades since in the 1880 U.S. Census, his occupation is listed as “dentist and merchant.” According to local historian Gary R. Freeze, Scott and Lowenstein were treated with some suspicion, with local residents warning people to “be cautious in dealing with them” because they were Jewish. Perhaps because of this frosty reception, Lowenstein moved to Statesville in 1881, where he became a successful liquor distiller. Scott remained in Hickory a bit longer, though he too had moved to Statesville by 1900.

Hickory did not develop a permanent Jewish population until the 1908 arrival of Louis Zerden, whose family would form the cornerstone of the town’s Jewish community for the next century. Zerden left Latvia in 1900 when he was 18, arriving in Baltimore. After working for cousins in Lewis, Delaware, Zerden began to peddle around the Atlantic seaboard. He consulted with the Baltimore Bargain House, a large Jewish-owned peddler supply company, about where he should open his own store. Given a list of towns in West Virginia and the Carolinas, Zerden chose Hickory after visiting the town in the midst of an economic boom. Between 1903 and 1909, Hickory’s population grew 50%, reaching 8,000 residents.

In September, 1908, Zerden opened his business, called “The Underselling Store,” though later the name would be changed to “Zerden’s.” While some locals initially saw this Jewish merchant as an exotic, and a few even thought he had horns, Zerden quickly became a popular business leader and his store an anchor in downtown’s Union Square. For some, the presence of a Jewish merchant like Zerden was a sign that Hickory had arrived economically. In a 1926 feature on Zerden in the Hickory Daily Record which described his original decision to settle in Hickory, the newspaper wrote, “if Mr. Zerden’s judgment is worth anything, and the people of his extraction have a universal reputation for being good business men, then Hickory is a wide awake town.” Louis Zerden married Sadye Bloom of Baltimore, who was 16 years his junior, and the two had six children, all of whom worked in the family business.

The first Jew to settle in Hickory was Lewis Elias, a merchant who moved to town from Statesville in 1861. Elias was one of the signers of the Hickory Tavern charter that officially incorporated the town in 1863. Elias did not remain in Hickory for very long, and had moved back to Statesville by 1870. In 1871, brothers-in-law Henry Scott and Julius Lowenstein, both of whom were German immigrants, opened a store in Hickory. Lowenstein was also a dentist, the first to settle in Hickory. Apparently, he plied both trades since in the 1880 U.S. Census, his occupation is listed as “dentist and merchant.” According to local historian Gary R. Freeze, Scott and Lowenstein were treated with some suspicion, with local residents warning people to “be cautious in dealing with them” because they were Jewish. Perhaps because of this frosty reception, Lowenstein moved to Statesville in 1881, where he became a successful liquor distiller. Scott remained in Hickory a bit longer, though he too had moved to Statesville by 1900.

Hickory did not develop a permanent Jewish population until the 1908 arrival of Louis Zerden, whose family would form the cornerstone of the town’s Jewish community for the next century. Zerden left Latvia in 1900 when he was 18, arriving in Baltimore. After working for cousins in Lewis, Delaware, Zerden began to peddle around the Atlantic seaboard. He consulted with the Baltimore Bargain House, a large Jewish-owned peddler supply company, about where he should open his own store. Given a list of towns in West Virginia and the Carolinas, Zerden chose Hickory after visiting the town in the midst of an economic boom. Between 1903 and 1909, Hickory’s population grew 50%, reaching 8,000 residents.

In September, 1908, Zerden opened his business, called “The Underselling Store,” though later the name would be changed to “Zerden’s.” While some locals initially saw this Jewish merchant as an exotic, and a few even thought he had horns, Zerden quickly became a popular business leader and his store an anchor in downtown’s Union Square. For some, the presence of a Jewish merchant like Zerden was a sign that Hickory had arrived economically. In a 1926 feature on Zerden in the Hickory Daily Record which described his original decision to settle in Hickory, the newspaper wrote, “if Mr. Zerden’s judgment is worth anything, and the people of his extraction have a universal reputation for being good business men, then Hickory is a wide awake town.” Louis Zerden married Sadye Bloom of Baltimore, who was 16 years his junior, and the two had six children, all of whom worked in the family business.

Melville's was started by Hersh Cohen

Melville's was started by Hersh Cohen

Other Jewish families eventually joined the Zerdens in Hickory. Ellis and Fannie Winter came to Hickory in the 1910s and opened a junk business. Harry and Abe Cohen owned Cohen’s Department Store, located next door to Zerden’s, by 1929. By 1939, Harry Cohen was the sole proprietor of the store. In 1936, Hersh Cohen opened Melville’s store, which remained in business for about half a century. Hickory developed a significant manufacturing base, especially in textiles and furniture. A few Jews were part of this industrial boom. In 1934, Pincus Lavitt and his family moved to Hickory and created the Knit-Sox Knitting Mills, which produced socks and hosiery for children. The family was from New York, and in 1962, the company’s president, Louis Lavitt, had his office in the Empire State Building. His siblings Sam Lavitt and Mrs. M.L. Nolanbogen still lived in Hickory and oversaw the factory. By 1937, 31 Jews lived in Hickory, while 22 lived in nearby Morganton.

Rabbi Friedman leads services on his bus

Rabbi Friedman leads services on his bus

Organized Jewish Life in Hickory

In the early 1930s, the small but growing Jewish population in Hickory began to organize. Under the leadership of Fannie Winters, they established a Sunday school, which attracted Jewish children from Hickory, Marion, Morganton, Lenoir, and Newton. The group began to meet together for religious services in the upstairs of the Old Moose Hall. Later, the group met in the auditorium of Lenoir-Rhyne College. The group hired Rabbi Phillip Frankel of Charlotte’s Reform Temple Beth-El to come to Hickory every other week to lead services. The relationship between the Hickory Jewish community and Temple Beth-El was further strengthened when the Sunday school was discontinued and Hickory’s Jewish youth traveled to Charlotte to receive their Jewish education.

Hickory’s Jewish community grew after World War II as the city became a furniture manufacturing center. By 1962, there were 74 furniture factories in Catawba County. By the end of the decade, the local furniture industry employed 10,000 people. While Jews were not directly involved in the furniture business, their stores benefited from the increased economic activity the industry produced.

In the 1950s, Hickory became one of the charter members of the circuit-riding rabbi program that was started by Charlotte businessman I.D. Blumenthal. Twice a month, Rabbi Harold Friedman would drive his bus, outfitted as a sanctuary, complete with an ark and Torah, to Hickory, where he would lead services, teach the children, and hold an adult education program. Later, the circuit riding rabbi gave up the bus, and would lead services at Lenoir-Rhyne College. The circuit riding rabbi program was designed to further develop Jewish religious life in North Carolina. In Hickory, the program was a complete success. With the prompting and support of I.D. Blumenthal and the circuit riding rabbi, Hickory Jews formally organized as the Hickory Jewish Center and purchased land for a synagogue. In January of 1959, they broke ground on their first building. They dedicated the center in September of that year in a public ceremony. Rabbi E.A. Levi of Charlotte’s Conservative congregation, Temple Israel, led the service. I.D. Blumenthal was given the honor of placing the Torah in the ark.

Despite this new building, most members of the Hickory Jewish Center still went elsewhere for the High Holidays in 1959. According to the local newspaper, Hickory Jews went to join family in Salisbury, Statesville, Greensboro, and High Point, North Carolina, for Rosh Hashanah. The Zerden family went to Hendersonville, which had an active congregation and several Jewish boarding houses. In the early years, the services at the Hickory Jewish Center were usually lay-led, as members used the Conservative prayer book. Although they chose the name “Hickory Jewish Center” so it would appeal to the entire Jewish community, regardless of religious background, the congregation officially joined the Conservative movement in 1960.

The Hickory Jewish Center was established by nine families, many of whom were bound together by economic or kinship ties: the Berndt family owned a jewelry and pawn shop, Philip and Gwen Zerden Datnoff were part of Zerden’s Department Store, Esther Greene, another daughter of Lewis Zerden, also worked at the family store, David Witten owned a scrap metal company, David Kraus worked for Witten’s scrap business, Marvin and Elaine Zerden ran Zerden’s, Sadye Zerden, Lewis’ widow, still owned the business, Sam Lavitt ran his family’s hosiery mill while his wife Edna was a pediatrician, and Sigbert Loeb, who owned a business in a small town outside of Hickory. Of the nine founding families, four were part of the extended Zerden family.

In the early 1930s, the small but growing Jewish population in Hickory began to organize. Under the leadership of Fannie Winters, they established a Sunday school, which attracted Jewish children from Hickory, Marion, Morganton, Lenoir, and Newton. The group began to meet together for religious services in the upstairs of the Old Moose Hall. Later, the group met in the auditorium of Lenoir-Rhyne College. The group hired Rabbi Phillip Frankel of Charlotte’s Reform Temple Beth-El to come to Hickory every other week to lead services. The relationship between the Hickory Jewish community and Temple Beth-El was further strengthened when the Sunday school was discontinued and Hickory’s Jewish youth traveled to Charlotte to receive their Jewish education.

Hickory’s Jewish community grew after World War II as the city became a furniture manufacturing center. By 1962, there were 74 furniture factories in Catawba County. By the end of the decade, the local furniture industry employed 10,000 people. While Jews were not directly involved in the furniture business, their stores benefited from the increased economic activity the industry produced.

In the 1950s, Hickory became one of the charter members of the circuit-riding rabbi program that was started by Charlotte businessman I.D. Blumenthal. Twice a month, Rabbi Harold Friedman would drive his bus, outfitted as a sanctuary, complete with an ark and Torah, to Hickory, where he would lead services, teach the children, and hold an adult education program. Later, the circuit riding rabbi gave up the bus, and would lead services at Lenoir-Rhyne College. The circuit riding rabbi program was designed to further develop Jewish religious life in North Carolina. In Hickory, the program was a complete success. With the prompting and support of I.D. Blumenthal and the circuit riding rabbi, Hickory Jews formally organized as the Hickory Jewish Center and purchased land for a synagogue. In January of 1959, they broke ground on their first building. They dedicated the center in September of that year in a public ceremony. Rabbi E.A. Levi of Charlotte’s Conservative congregation, Temple Israel, led the service. I.D. Blumenthal was given the honor of placing the Torah in the ark.

Despite this new building, most members of the Hickory Jewish Center still went elsewhere for the High Holidays in 1959. According to the local newspaper, Hickory Jews went to join family in Salisbury, Statesville, Greensboro, and High Point, North Carolina, for Rosh Hashanah. The Zerden family went to Hendersonville, which had an active congregation and several Jewish boarding houses. In the early years, the services at the Hickory Jewish Center were usually lay-led, as members used the Conservative prayer book. Although they chose the name “Hickory Jewish Center” so it would appeal to the entire Jewish community, regardless of religious background, the congregation officially joined the Conservative movement in 1960.

The Hickory Jewish Center was established by nine families, many of whom were bound together by economic or kinship ties: the Berndt family owned a jewelry and pawn shop, Philip and Gwen Zerden Datnoff were part of Zerden’s Department Store, Esther Greene, another daughter of Lewis Zerden, also worked at the family store, David Witten owned a scrap metal company, David Kraus worked for Witten’s scrap business, Marvin and Elaine Zerden ran Zerden’s, Sadye Zerden, Lewis’ widow, still owned the business, Sam Lavitt ran his family’s hosiery mill while his wife Edna was a pediatrician, and Sigbert Loeb, who owned a business in a small town outside of Hickory. Of the nine founding families, four were part of the extended Zerden family.

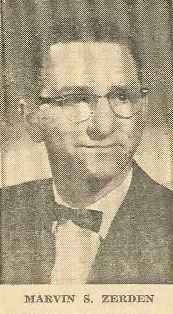

Marvin Zerden became the general manager of Zerden’s after his father Louis died in 1951. Marvin’s older brother Glenn had died during World War II after his ship, the Dorchester, was sunk by a German submarine. Born and raised in Hickory, Marvin would later be described as “the grand old man of downtown retailing” by the local newspaper. Zerden served as president of the Downtown Development Association, and led the way in getting the Southern Railways to relocate its switching station to aid additional downtown development. Even when shopping centers and malls began to proliferate, Zerden kept his business downtown on Union Square. Zerden was extremely active in the larger community, serving on the boards of the Greater Hickory United Fund, the local Red Cross, and the Hickory Human Relations Council. He was also involved in the Jewish community, spending 30 years as head of the United Jewish Communities in Hickory and serving as longtime leader of the local B’nai B’rith chapter, which had been named after his brother Glenn. Zerden became a beloved figure in Hickory; when he died in 2008, the local newspaper editorialized, “enumerating his service to the community would fill a book, so we’ll just reiterate: Hickory…won’t be the same without Marvin Zerden.”

The Hickory Jewish Center quickly flourished in its new home. One of their highest priorities was the education of their children, and in 1962, the congregation hired Dr. William Furie to be their education director. The congregation had twenty children and five teachers in its religious school at the time. As the only Jewish congregation in the county, the Hickory Jewish Center made a special effort to build interfaith relationships in the community. Many church groups toured the Hickory Jewish Center after it opened to learn about Judaism. In 1965, the congregation participated in a model Passover seder for local Christians. In 1971, they began taking part in an annual tradition of holding an interfaith Thanksgiving service with local churches. Later, the churches that took part in the interfaith service would donate to the Hickory Jewish Center’s new building fund.

The Hickory Jewish Center quickly flourished in its new home. One of their highest priorities was the education of their children, and in 1962, the congregation hired Dr. William Furie to be their education director. The congregation had twenty children and five teachers in its religious school at the time. As the only Jewish congregation in the county, the Hickory Jewish Center made a special effort to build interfaith relationships in the community. Many church groups toured the Hickory Jewish Center after it opened to learn about Judaism. In 1965, the congregation participated in a model Passover seder for local Christians. In 1971, they began taking part in an annual tradition of holding an interfaith Thanksgiving service with local churches. Later, the churches that took part in the interfaith service would donate to the Hickory Jewish Center’s new building fund.

The first synagogoue of the Hickory Jewish Center

The first synagogoue of the Hickory Jewish Center

The Hickory Jewish Center relied on lay leaders and a series of visiting rabbis to lead services over the years. In 1975, they hired H. Richard Brown, a cantor ordained from Hebrew Union College, as their first full-time spiritual leader. Perhaps connected with his hiring, the congregation left the Conservative Movement. Brown introduced Reform rituals, including the congregation’s first confirmation ceremony in 1976. Although Cantor Brown left in 1976, the Hickory Jewish Center continued its drift toward Reform Judaism, hiring a female student rabbi from the Reform Hebrew Union College. Rabbinic student Ellen Weinberg came to Hickory twice a month and introduced the new Reform prayer book to the congregation. After Weinberg’s tenure, the congregation went back to bringing visiting and retired rabbis once a month to lead services. Phil Datnoff often served as lay leader when the visiting rabbi was not in town and tutored many boys and girls for their b’nei mitzvah cermonies. In 1980, the congregation gave Datnoff their first extraordinary service award. In 2002, they dedicated a memorial garden at the temple in Datnoff’s honor.

Hickory Jews established other organizations, although they were usually outgrowths of the Hickory Jewish Center. The women in the congregation established a Sisterhood, while men created a B’nai B’rith chapter. In 1959, Hickory joined together with the Jewish communities of Salisbury and Statesville to create a chapter of the B’nai B’rith Youth Organization. The teenaged members of the group would meet each Sunday afternoon in one of the three towns. The members would go to regional events where they would socialize with Jews from larger cities. According to a 1984 history of the Hickory Jewish Center, “BBYO was one of the few links the 13-18 year-old Jewish children had with others of similar background.” For a while, Hickory’s congregation was closely linked to those in Salisbury and Statesville. Children from the other towns would go to Sunday school in Hickory, and families in the different communities would attend each other’s b'nei mitzvah. This close connection between the three communities has diminished of late as Salisbury and Statesville’s congregations have seen sharp declines in their membership and the number of Jewish children in each town has dwindled.

Hickory Jews established other organizations, although they were usually outgrowths of the Hickory Jewish Center. The women in the congregation established a Sisterhood, while men created a B’nai B’rith chapter. In 1959, Hickory joined together with the Jewish communities of Salisbury and Statesville to create a chapter of the B’nai B’rith Youth Organization. The teenaged members of the group would meet each Sunday afternoon in one of the three towns. The members would go to regional events where they would socialize with Jews from larger cities. According to a 1984 history of the Hickory Jewish Center, “BBYO was one of the few links the 13-18 year-old Jewish children had with others of similar background.” For a while, Hickory’s congregation was closely linked to those in Salisbury and Statesville. Children from the other towns would go to Sunday school in Hickory, and families in the different communities would attend each other’s b'nei mitzvah. This close connection between the three communities has diminished of late as Salisbury and Statesville’s congregations have seen sharp declines in their membership and the number of Jewish children in each town has dwindled.

Colony Casuals

Colony Casuals

The 1980s and 1990s

If Salisbury and Statesville have declined in recent decades, Hickory has flourished, reaching its apex in the 1980s and 1990s. Around that time, an increasing number of Jewish professionals, often from the northeast, moved to Hickory, usually working for large corporations like General Electric that had opened facilities in the area. The local fiber optics industry also attracted Jewish engineers, scientists, and business executives. A growing number of Jewish doctors were attracted to the area. Dr. Sandy Guttler and his wife Linda moved to Hickory in 1979 and have been leaders in the congregation ever since. In addition to this influx of professionals, there were still several Jewish merchants in Hickory. Zerden’s remained a downtown institution while Marvin Zerden’s younger brother Howard opened Colony Casuals, a women’s clothing store, in 1960. Pauline Lavitt, who helped start the Paul Lavitt Mills with her husband, opened a high-end women’s clothing boutique in the early 1970s. The Berndt family, who came to Hickory after World War II, opened an Army/Navy Store and Pawn Shop that remains in business today.

If Salisbury and Statesville have declined in recent decades, Hickory has flourished, reaching its apex in the 1980s and 1990s. Around that time, an increasing number of Jewish professionals, often from the northeast, moved to Hickory, usually working for large corporations like General Electric that had opened facilities in the area. The local fiber optics industry also attracted Jewish engineers, scientists, and business executives. A growing number of Jewish doctors were attracted to the area. Dr. Sandy Guttler and his wife Linda moved to Hickory in 1979 and have been leaders in the congregation ever since. In addition to this influx of professionals, there were still several Jewish merchants in Hickory. Zerden’s remained a downtown institution while Marvin Zerden’s younger brother Howard opened Colony Casuals, a women’s clothing store, in 1960. Pauline Lavitt, who helped start the Paul Lavitt Mills with her husband, opened a high-end women’s clothing boutique in the early 1970s. The Berndt family, who came to Hickory after World War II, opened an Army/Navy Store and Pawn Shop that remains in business today.

Current home of the Hickory Jewish Center, built in 1989.

Current home of the Hickory Jewish Center, built in 1989.

This growth in the Hickory Jewish community had a significant impact on the congregation. In the early 1980s, the congregation grew from 25 to 40 member families. Most of this growth consisted of young families with children, and the Hickory Jewish Center’s Sunday school was soon bursting at the seams. By 1984, they had 27 children under the age of 10. Their small 1,300 square foot building was simply too small to accommodate the growing congregation. As a result, members began to discuss building a new synagogue. They bought land in 1984, and began the long, slow process of raising the money for the new structure. The following year, the congregation also acquired land for a cemetery, the first Jewish burial ground in Hickory. Finally, in 1988, the congregation broke ground on their new building. In August, 1989, they dedicated a new 6,000 square foot temple. In honor of their new home, they changed their name to Temple Beth Shalom – Hickory Jewish Center. The congregation grew from 40 families in 1984 to 64 in 2002.

The growing number of Jewish professionals has helped keep Temple Beth Shalom strong, even as most Jewish-owned retail businesses in Hickory have closed. In recent decades, the furniture manufacturing industry has largely disappeared as companies have moved their plants overseas. This decline has hurt the city’s retail stores, which also faced new competition from chain stores and malls. Many of the Jewish children raised in Hickory moved away to larger cities and had little interest in taking over the family business. Melville’s closed in the 1980s, while Pauline Lavitt closed in the 1990s. Zerden’s finally closed in 1999, after almost a century of doing business on Union Square. Colony Casuals shut its doors in 2002.

The growing number of Jewish professionals has helped keep Temple Beth Shalom strong, even as most Jewish-owned retail businesses in Hickory have closed. In recent decades, the furniture manufacturing industry has largely disappeared as companies have moved their plants overseas. This decline has hurt the city’s retail stores, which also faced new competition from chain stores and malls. Many of the Jewish children raised in Hickory moved away to larger cities and had little interest in taking over the family business. Melville’s closed in the 1980s, while Pauline Lavitt closed in the 1990s. Zerden’s finally closed in 1999, after almost a century of doing business on Union Square. Colony Casuals shut its doors in 2002.

The Jewish Community in Hickory Today

Despite the disappearance of most of these Jewish-owned stores, the Hickory Jewish community has remained strong. In 1998, they affiliated with the Reform Movement in order to have access to student rabbis from Hebrew Union College. The student rabbis would come once a month, leading Shabbat services on Friday night and Saturday morning, as well as an adult education program on Saturday night. In 2008, the congregation went back to having retired rabbis. While the congregation is officially Reform, it has members from Conservative and Orthodox backgrounds. The temple’s kitchen is “kosher-style,” with restrictions on pork, shellfish, and the mixing of milk and meat. There is still a small, but active religious school, even though the congregation does not have as many young families as it had back in the 1980s. Members of Temple Beth Shalom continue to act as civic leaders in the larger community, with Mel Cohen serving as mayor of nearby Morganton for well over 20 years. Hickory’s Jewish community has successfully managed the transition from retail to professional occupations, and remains a vital outpost of Jewish life in western North Carolina.