Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Weldon, North Carolina

Overview >> North Carolina >> Weldon

Weldon: Historical Overview

Weldon, North Carolina, was originally called “Weldon’s Orchard” after founder Daniel Weldon planted an orchard in the spot where the town now stands. The town itself was founded in 1745 and was the head of navigation on the Roanoke River. After the Roanoke Canal was built in 1823, the economy boomed as boat traffic to Virginia came through Weldon. In 1840, the Wilmington to Weldon Railroad was completed. Stretching 161 miles, the longest in the world at that time, the railroad ended in Weldon. Despite its long history dating back to the 19th century, Weldon did not have a permanent Jewish community until the later part of the 19th century. A bit earlier, Jews settled in the nearby towns of Enfield, Halifax, and Scotland Neck.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Weldon

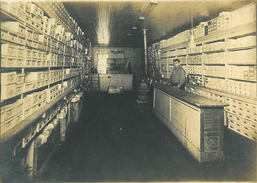

Louis Kittner in his shoe store, 1917

Louis Kittner in his shoe store, 1917

Early Settlers

While there is a Revolutionary War record of a man named Abraham Moses from Halifax County in 1783, there is no way to know if he was Jewish. It would be another century before Weldon saw a permanent Jewish presence. One of the first Jews who came to Weldon to stay was Henry Farber. Farber came from Sadvia, Lithuania in 1890. He started out as a peddler, selling wares from a backpack, until he had enough money to buy a horse and wagon. Eventually, he had enough money to settle down, and, in 1892, moved to Weldon. Together with an in-law, Louis Levin, he purchased the dry goods store of Max Friedlander, who had moved to Clifton Forge, Virginia. At the time of the 1900 census, Levin and Farber were living together in a rented house and running their dry goods store.

Farber brought many of his relatives to the area, establishing the foundation of the local Jewish community. In 1902, Henry married his cousin, Mollie Farber, in Baltimore and then brought his mother and four sisters to the United States. With the money he was making, Henry was able to finance stores for his brothers-in-law, Hyman Joblin and Hyman Silvester in Warrenton, North Carolina. Henry’s sister Rosa, and her husband Morris Freid, moved to Weldon when a store became available in 1906. When the husband of one of his sister’s died, Farber took in his nephews, Bill and Mike Josephson. Eventually, Henry and Mike Josephson became partners in one store, while Bill operated another store called The Leader.

The Jews who followed the Farber family to Weldon also concentrated in retail trade. Even those who started out as skilled laborers ended up owning retail stores. A shoe repairman by trade, Louis Kittner left Poland in 1912, settling first in Philadelphia. After a period living with an uncle in Petersburg, Virginia, Kittner moved to Weldon and opened a shoe repair shop. This small shop soon expanded into a retail shoe store, and later into Kittner’s Department Store, which remained in business in Weldon for over 80 years. By 1917, there were five Jewish-owned stores in Weldon, and several others in nearby towns like Roanoke Rapids and Emporia, Virginia. Russian-born immigrant Benjamin Marks owned a department store in Roanoke Rapids by 1910. In Weldon, the businesses were clustered around the town’s railroad depot.

While there is a Revolutionary War record of a man named Abraham Moses from Halifax County in 1783, there is no way to know if he was Jewish. It would be another century before Weldon saw a permanent Jewish presence. One of the first Jews who came to Weldon to stay was Henry Farber. Farber came from Sadvia, Lithuania in 1890. He started out as a peddler, selling wares from a backpack, until he had enough money to buy a horse and wagon. Eventually, he had enough money to settle down, and, in 1892, moved to Weldon. Together with an in-law, Louis Levin, he purchased the dry goods store of Max Friedlander, who had moved to Clifton Forge, Virginia. At the time of the 1900 census, Levin and Farber were living together in a rented house and running their dry goods store.

Farber brought many of his relatives to the area, establishing the foundation of the local Jewish community. In 1902, Henry married his cousin, Mollie Farber, in Baltimore and then brought his mother and four sisters to the United States. With the money he was making, Henry was able to finance stores for his brothers-in-law, Hyman Joblin and Hyman Silvester in Warrenton, North Carolina. Henry’s sister Rosa, and her husband Morris Freid, moved to Weldon when a store became available in 1906. When the husband of one of his sister’s died, Farber took in his nephews, Bill and Mike Josephson. Eventually, Henry and Mike Josephson became partners in one store, while Bill operated another store called The Leader.

The Jews who followed the Farber family to Weldon also concentrated in retail trade. Even those who started out as skilled laborers ended up owning retail stores. A shoe repairman by trade, Louis Kittner left Poland in 1912, settling first in Philadelphia. After a period living with an uncle in Petersburg, Virginia, Kittner moved to Weldon and opened a shoe repair shop. This small shop soon expanded into a retail shoe store, and later into Kittner’s Department Store, which remained in business in Weldon for over 80 years. By 1917, there were five Jewish-owned stores in Weldon, and several others in nearby towns like Roanoke Rapids and Emporia, Virginia. Russian-born immigrant Benjamin Marks owned a department store in Roanoke Rapids by 1910. In Weldon, the businesses were clustered around the town’s railroad depot.

Organized Jewish Life in Weldon

As the Jewish population of Weldon and the surrounding towns grew, Henry Farber took the lead in organizing a congregation. The impetus was their desire to pass down their Jewish traditions to their children. Thus, the group quickly established a religious school after creating the congregation in 1912. The school initially met at the home of Henry and Mollie Farber. The congregation also met in private homes initially. The Weldon congregation was traditional as most members came from Orthodox backgrounds, though even early on there was a tension between maintaining traditional practice and living in a small Southern town. Members kept their stores open on Saturday, the Jewish Sabbath, since that was their busiest day of the week. Yet many members of the congregation kept kosher; several members slaughtered their own chickens. They would bring in a shochet from Raleigh to slaughter cows, and later ordered kosher meat from Norfolk or Richmond. Several families sent their boys to live with relatives in Baltimore and other large cities for their bar mitzvah year so they would receive training in Hebrew, which they evidently could not receive in Weldon.

In 1928, the group created a sanctuary and meeting space upstairs from Silvester’s Clothing Store, calling it the Hebrew Community Center of Weldon and Roanoke Rapids. Henry Farber built an ark out of shipping crates to sit on the small bimah. There were two small classrooms in back that were used for religious school. Once again, the congregation worked to balance traditional worship with economic reality. Women sat in back of the sanctuary, separate from the men, during the Orthodox prayers, though the congregation only held Shabbat services on Friday night. By 1939, the congregation had begun to move away from Orthodoxy, and brought in student rabbis from the Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary in New York to lead High Holiday services.

After World War II

After World War II, the Weldon area began to flourish economically. The Jewish-owned stores thrived as well. Fannye Marks’ women’s clothing store Fannye’s became an institution. The wives of congressmen and governors shopped at her high-end boutique in Roanoke Rapids, where customers were served by appointment only. Some of the second generation of Weldon’s original Jewish settlers left the area for greater opportunity, but others remained to take over family businesses. Henry Farber’s son Herman became a doctor in Petersburg, Virginia, while oldest son Ellis left college to help run the family store in Scotland Neck. Only two of Louis and Rose Kittner’s six children stayed in Weldon. Older sons David and Joseph became lawyers in large northeastern cities, while Harry and Bill Kittner remained in the area to run Kittner’s Department Store.

After the war, the Jewish community began to discuss building a permanent synagogue for the congregation, even appointing a fundraising committee in 1948. There was much debate over whether to build the synagogue in Weldon or Roanoke Rapids. Unable to find suitable land, the congregation decided to renovate the rooms in the Hebrew Community Center in 1950. Finally, in 1954, Harry Kittner found a house in Weldon that was being sold at auction. He convinced the other members that the house could be remodeled into a synagogue, and the group bought the home for $10,000. Twenty-three members pledged almost $16,000 to cover the cost of the house and its remodeling. The new synagogue was small, although its 52-seat sanctuary could be augmented with an additional 32 seats if the social room were opened up. At the time of the building’s dedication, the congregation had 28 member families. Eleven families lived in Weldon while seven resided in Roanoke Rapids and another seven in Emporia.

In addition to a new building, the congregation also made other changes, including its name, becoming known as Temple Emanu-El. The congregation also officially joined the Conservative movement, affiliating with the United Synagogue of America. Conservative Judaism, with its attempts to balance Jewish tradition with modern life, was a better fit for a congregation largely made up of native-born Americans. In 1957, the congregation introduced a piano to Shabbat services, against the wishes of some of the old-timers. Temple Emanu-El members also began to move out of downtown towards the suburbs in the 1950s, mirroring national trends. As Jews bought houses in the suburbs, they were no longer able to walk to synagogue on Jewish holidays, another example of the second generation’s movement away from strict traditional practice. Over the years, fewer and fewer congregation members kept strict kosher.

At the dedication of Temple Emanu-El’s new synagogue, Rabbi Harold Friedman gave the invocation. Friedman was a circuit-riding rabbi recently hired by Charlotte businessman I.D. Blumenthal to serve small Jewish congregations in the Carolinas. Members of Temple Emanu-El pledged $840 a year to help support the program. Rabbi Friedman made regular visits to Weldon during his tenure as a circuit-rider. During his visits, he would lead services and teach both the children and adults of the congregation. For the High Holidays, Emanu-El brought in visiting rabbis. Otherwise, William Farber would lead services as lay reader. Later, Bob Liverman would serve as lay leader while Ellis Farber, the longtime president of the congregation, would give sermons and Torah lessons.

The congregation was small and spread out over seven different towns in the area, yet its membership was still very close-knit. One reason for this was that some local Jewish families had intermarried with each other. Another was the intimacy of a small congregation. For the rest of the week, members lived and worked among Gentiles, but on Friday night and Jewish holidays, they were able to exist in a Jewish world. After Friday night services, members socialized together at an oneg reception. On Rosh Hashanah, members would gather together for a meal at the local Holiday Inn, whose restaurant was run by congregant Harold Bloom. Starting in 1954, Emanu-El held an annual community seder for Passover, a tradition which lasted for fifty years. By 1967, Temple Emanu-El had 34 members, along with 33 associate members who no longer lived in the region but continued to support the congregation. In 1969, they acquired land for a cemetery in Roanoke Rapids. Previously, Weldon Jews had buried their dead in Richmond or Petersburg, Virginia.

As the Jewish population of Weldon and the surrounding towns grew, Henry Farber took the lead in organizing a congregation. The impetus was their desire to pass down their Jewish traditions to their children. Thus, the group quickly established a religious school after creating the congregation in 1912. The school initially met at the home of Henry and Mollie Farber. The congregation also met in private homes initially. The Weldon congregation was traditional as most members came from Orthodox backgrounds, though even early on there was a tension between maintaining traditional practice and living in a small Southern town. Members kept their stores open on Saturday, the Jewish Sabbath, since that was their busiest day of the week. Yet many members of the congregation kept kosher; several members slaughtered their own chickens. They would bring in a shochet from Raleigh to slaughter cows, and later ordered kosher meat from Norfolk or Richmond. Several families sent their boys to live with relatives in Baltimore and other large cities for their bar mitzvah year so they would receive training in Hebrew, which they evidently could not receive in Weldon.

In 1928, the group created a sanctuary and meeting space upstairs from Silvester’s Clothing Store, calling it the Hebrew Community Center of Weldon and Roanoke Rapids. Henry Farber built an ark out of shipping crates to sit on the small bimah. There were two small classrooms in back that were used for religious school. Once again, the congregation worked to balance traditional worship with economic reality. Women sat in back of the sanctuary, separate from the men, during the Orthodox prayers, though the congregation only held Shabbat services on Friday night. By 1939, the congregation had begun to move away from Orthodoxy, and brought in student rabbis from the Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary in New York to lead High Holiday services.

After World War II

After World War II, the Weldon area began to flourish economically. The Jewish-owned stores thrived as well. Fannye Marks’ women’s clothing store Fannye’s became an institution. The wives of congressmen and governors shopped at her high-end boutique in Roanoke Rapids, where customers were served by appointment only. Some of the second generation of Weldon’s original Jewish settlers left the area for greater opportunity, but others remained to take over family businesses. Henry Farber’s son Herman became a doctor in Petersburg, Virginia, while oldest son Ellis left college to help run the family store in Scotland Neck. Only two of Louis and Rose Kittner’s six children stayed in Weldon. Older sons David and Joseph became lawyers in large northeastern cities, while Harry and Bill Kittner remained in the area to run Kittner’s Department Store.

After the war, the Jewish community began to discuss building a permanent synagogue for the congregation, even appointing a fundraising committee in 1948. There was much debate over whether to build the synagogue in Weldon or Roanoke Rapids. Unable to find suitable land, the congregation decided to renovate the rooms in the Hebrew Community Center in 1950. Finally, in 1954, Harry Kittner found a house in Weldon that was being sold at auction. He convinced the other members that the house could be remodeled into a synagogue, and the group bought the home for $10,000. Twenty-three members pledged almost $16,000 to cover the cost of the house and its remodeling. The new synagogue was small, although its 52-seat sanctuary could be augmented with an additional 32 seats if the social room were opened up. At the time of the building’s dedication, the congregation had 28 member families. Eleven families lived in Weldon while seven resided in Roanoke Rapids and another seven in Emporia.

In addition to a new building, the congregation also made other changes, including its name, becoming known as Temple Emanu-El. The congregation also officially joined the Conservative movement, affiliating with the United Synagogue of America. Conservative Judaism, with its attempts to balance Jewish tradition with modern life, was a better fit for a congregation largely made up of native-born Americans. In 1957, the congregation introduced a piano to Shabbat services, against the wishes of some of the old-timers. Temple Emanu-El members also began to move out of downtown towards the suburbs in the 1950s, mirroring national trends. As Jews bought houses in the suburbs, they were no longer able to walk to synagogue on Jewish holidays, another example of the second generation’s movement away from strict traditional practice. Over the years, fewer and fewer congregation members kept strict kosher.

At the dedication of Temple Emanu-El’s new synagogue, Rabbi Harold Friedman gave the invocation. Friedman was a circuit-riding rabbi recently hired by Charlotte businessman I.D. Blumenthal to serve small Jewish congregations in the Carolinas. Members of Temple Emanu-El pledged $840 a year to help support the program. Rabbi Friedman made regular visits to Weldon during his tenure as a circuit-rider. During his visits, he would lead services and teach both the children and adults of the congregation. For the High Holidays, Emanu-El brought in visiting rabbis. Otherwise, William Farber would lead services as lay reader. Later, Bob Liverman would serve as lay leader while Ellis Farber, the longtime president of the congregation, would give sermons and Torah lessons.

The congregation was small and spread out over seven different towns in the area, yet its membership was still very close-knit. One reason for this was that some local Jewish families had intermarried with each other. Another was the intimacy of a small congregation. For the rest of the week, members lived and worked among Gentiles, but on Friday night and Jewish holidays, they were able to exist in a Jewish world. After Friday night services, members socialized together at an oneg reception. On Rosh Hashanah, members would gather together for a meal at the local Holiday Inn, whose restaurant was run by congregant Harold Bloom. Starting in 1954, Emanu-El held an annual community seder for Passover, a tradition which lasted for fifty years. By 1967, Temple Emanu-El had 34 members, along with 33 associate members who no longer lived in the region but continued to support the congregation. In 1969, they acquired land for a cemetery in Roanoke Rapids. Previously, Weldon Jews had buried their dead in Richmond or Petersburg, Virginia.

Civic Engagement

Jews enjoyed a significant degree of social acceptance in the area and got closely involved in civic affairs. Henry Farber was an active Mason and served on the Weldon Town Council in the 1920s. David Bloom spent thirty years on the Emporia city council. Bloom was a charitable and beloved local figure. He would continue to give clothes to needy people on credit even if they had been unable to pay their debts. He quietly paid hospital and funeral bills and donated money to those in need. When he died in 1969, Emporia lowered its flags to half-mast and many businesses closed so people could attend the funeral. Fannye Marks raised a lot of money for local charities through benefit events. In 1995, Roanoke Rapids thanked her by celebrating “Fannye’s Day” with a public event that drew hundreds of participants.

Jews were especially involved in economic development, education, and health care, working hard to improve the quality of life in the area. Eugene Bloom was a founder and leader of the Emporia-Greensville Industrial Development Corporation, which worked to attract industry to the area. Bloom started the Virginia Peanut Festival, which became a big draw for local tourism, and served as president of the Emporia Chamber of Commerce. Bill Kittner was head of the Weldon Chamber of Commerce. Sarah Kittner served many years on the board of the Halifax Community College, and was named its chair in 1996. She and her husband Harry endowed a scholarship at the college in honor of Louis and Rose Kittner. Harry also served as chairman of the board of the Halifax Memorial Hospital, while Eugene Bloom led the way in getting the first hospital built in Emporia. Bob Liverman served on the local Human Relations Committee, which worked to improve race relations in Roanoke Rapids. He also spent 26 years as the chairman of the local Housing Authority, which built public housing.

Anti-Semitism in Weldon

Despite these remarkable contributions, area Jews did face occasional anti-Semitism. Harry Kittner was blackballed from the local Rotary Club because of his religion, and some local women’s clubs did not accept Jewish members. This exclusion varied from town to town in the area. While Jews were barred from the Weldon Country Club for many years, they were always accepted at the country clubs in Emporia and Scotland Neck, where Ellis Farber was a founding member.

Jews enjoyed a significant degree of social acceptance in the area and got closely involved in civic affairs. Henry Farber was an active Mason and served on the Weldon Town Council in the 1920s. David Bloom spent thirty years on the Emporia city council. Bloom was a charitable and beloved local figure. He would continue to give clothes to needy people on credit even if they had been unable to pay their debts. He quietly paid hospital and funeral bills and donated money to those in need. When he died in 1969, Emporia lowered its flags to half-mast and many businesses closed so people could attend the funeral. Fannye Marks raised a lot of money for local charities through benefit events. In 1995, Roanoke Rapids thanked her by celebrating “Fannye’s Day” with a public event that drew hundreds of participants.

Jews were especially involved in economic development, education, and health care, working hard to improve the quality of life in the area. Eugene Bloom was a founder and leader of the Emporia-Greensville Industrial Development Corporation, which worked to attract industry to the area. Bloom started the Virginia Peanut Festival, which became a big draw for local tourism, and served as president of the Emporia Chamber of Commerce. Bill Kittner was head of the Weldon Chamber of Commerce. Sarah Kittner served many years on the board of the Halifax Community College, and was named its chair in 1996. She and her husband Harry endowed a scholarship at the college in honor of Louis and Rose Kittner. Harry also served as chairman of the board of the Halifax Memorial Hospital, while Eugene Bloom led the way in getting the first hospital built in Emporia. Bob Liverman served on the local Human Relations Committee, which worked to improve race relations in Roanoke Rapids. He also spent 26 years as the chairman of the local Housing Authority, which built public housing.

Anti-Semitism in Weldon

Despite these remarkable contributions, area Jews did face occasional anti-Semitism. Harry Kittner was blackballed from the local Rotary Club because of his religion, and some local women’s clubs did not accept Jewish members. This exclusion varied from town to town in the area. While Jews were barred from the Weldon Country Club for many years, they were always accepted at the country clubs in Emporia and Scotland Neck, where Ellis Farber was a founding member.

The Community Declines

In recent decades, many of the area’s textile mills have closed while chain discount stores have brought steep competition for downtown merchants. As a result, Jewish-owned stores began to close in the 1970s and 80s. In 1998, Kittner’s Department Store closed after being in business in Weldon for over eight decades. In many cases, the stores were closed after their owners’ children left for larger cities in search of greater economic and social opportunities. Most of the Jewish community’s 3rd generation moved away to places like Atlanta, Washington, D.C., and Charlotte. Those who stayed, like Steve Bloom and Mark Novey, tended to be professionals rather than retail businessmen.

These economic changes had a profound impact on Temple Emanu-El. In 1976, Emanu-El joined the Reform Union of American Hebrew Congregations, completing its transition away from its Orthodox roots. After the circuit-riding rabbi program ended in 1979, the congregation started getting student rabbis from Hebrew Union College. Despite these changes, the congregation went into decline. In 1988, Emanu-El had 27 member families, or 61 people in all. In 1993, the congregation no longer had rabbinic students or visiting rabbis, relying instead of member Bob Liverman to lead services. Longtime leaders like Ellis Farber and Fannye Marks passed away, while several retired members moved away from Weldon to be closer to their children and grandchildren. Despite this decline, Temple Emanu-El still attracted a large crowd on most High Holidays as the children raised in the congregation came back to be with their families.

In recent decades, many of the area’s textile mills have closed while chain discount stores have brought steep competition for downtown merchants. As a result, Jewish-owned stores began to close in the 1970s and 80s. In 1998, Kittner’s Department Store closed after being in business in Weldon for over eight decades. In many cases, the stores were closed after their owners’ children left for larger cities in search of greater economic and social opportunities. Most of the Jewish community’s 3rd generation moved away to places like Atlanta, Washington, D.C., and Charlotte. Those who stayed, like Steve Bloom and Mark Novey, tended to be professionals rather than retail businessmen.

These economic changes had a profound impact on Temple Emanu-El. In 1976, Emanu-El joined the Reform Union of American Hebrew Congregations, completing its transition away from its Orthodox roots. After the circuit-riding rabbi program ended in 1979, the congregation started getting student rabbis from Hebrew Union College. Despite these changes, the congregation went into decline. In 1988, Emanu-El had 27 member families, or 61 people in all. In 1993, the congregation no longer had rabbinic students or visiting rabbis, relying instead of member Bob Liverman to lead services. Longtime leaders like Ellis Farber and Fannye Marks passed away, while several retired members moved away from Weldon to be closer to their children and grandchildren. Despite this decline, Temple Emanu-El still attracted a large crowd on most High Holidays as the children raised in the congregation came back to be with their families.

The Jewish Community in Weldon Today

By the late 1990s, the leaders of the congregation grew concerned about the future. In 1999, they held a meeting to discuss the potential closure of the synagogue. When Bill Kittner, who had been leading services, moved to Norfolk in 2000, members realized that the congregation could not continue. After much discussion, the congregation voted to disband and sell their building. Emanu-El’s Judaica was distributed to various places: its memorial plaques and one Torah went to a congregation in Virginia Beach; another Torah went to a new congregation in Concord, North Carolina; the ark and stained glass windows went to a new chapel at the Jewish old age home in Virginia Beach; while other artifacts went to the Chapel Hill Kehillah. In 2006, Temple Emanu-El’s building was sold to a local church.

While other Jewish communities in North Carolina have thrived over the last few decades, the experience of Weldon’s Temple Emanu-El shows that the state has not escaped the demographic decline that has affected small Jewish communities across the South.

While other Jewish communities in North Carolina have thrived over the last few decades, the experience of Weldon’s Temple Emanu-El shows that the state has not escaped the demographic decline that has affected small Jewish communities across the South.

Sources

Rogoff, Leonard. A History of Temple Emanu-El: An Extended Family. Durham: Jewish Heritage Foundation of North Carolina, 2007.