Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Bogalusa, Louisiana

Bogalusa: Historical Overview

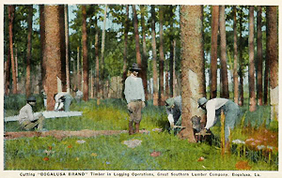

Bogalusa has always been defined by its industry: first lumber and then paper. Located in the heart of the Pinelands region of southeastern Louisiana, Bogalusa was founded in 1906 as the site of a massive sawmill. The Great Southern Lumber Company, owned by the Goodyear family of Buffalo, New York, incorporated the town and opened the sawmill in 1908. Within several months, the population of this settlement among emerald swamps and endless forests had grown to 8,000. Jews and non-Jews alike relocated to Bogalusa in order to fill thousands of available jobs at the sawmill or to open businesses catering to this rapidly expanding economy.

At the turn of the 20th century, Bogalusa was a frontier town, lacking the amenities of more established cities. With the construction of a sawmill and a railroad connecting it with New Orleans and Jackson, Mississippi, however, Bogalusa soon emerged as one of Louisiana’s chief industrial hubs. Over ten thousand people moved to the city within ten years of the sawmill’s opening, many of whom worked in what was then the largest yellow pine sawmill in the world. Many Jews, especially Polish and Russian immigrants, left their homes in New York and New Orleans after hearing about opportunities in Bogalusa.

By the mid-20th century, over 50 Jewish families resided in Bogalusa. They operated successful businesses, organized a congregation, and filled integral roles in the growth of the city’s booming lumber industry. Jewish residents also played a major part in the city's civic life, joining fraternal and charitable organizations and serving on the board of the local bank.

At the turn of the 20th century, Bogalusa was a frontier town, lacking the amenities of more established cities. With the construction of a sawmill and a railroad connecting it with New Orleans and Jackson, Mississippi, however, Bogalusa soon emerged as one of Louisiana’s chief industrial hubs. Over ten thousand people moved to the city within ten years of the sawmill’s opening, many of whom worked in what was then the largest yellow pine sawmill in the world. Many Jews, especially Polish and Russian immigrants, left their homes in New York and New Orleans after hearing about opportunities in Bogalusa.

By the mid-20th century, over 50 Jewish families resided in Bogalusa. They operated successful businesses, organized a congregation, and filled integral roles in the growth of the city’s booming lumber industry. Jewish residents also played a major part in the city's civic life, joining fraternal and charitable organizations and serving on the board of the local bank.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Bogalusa

The Berenson Family

Shortly after the Great Southern Lumber Company founded its mill in 1906, Jews such as Polish immigrant Meyer Berenson arrived in Bogalusa to make their fortunes. Meyer came to Bogalusa at the age of 16 and shortly after opened a store with a fellow Jew. The store did not prove to be a success, so when his brother Elias arrived several years later, they opened Berenson Brothers department store on Columbia Road. This store thrived as Bogalusa experienced a massive influx of mill workers and, in turn, the Berenson family acquired a great deal of wealth.

In 1929, the Berenson family built a large theater in downtown Bogalusa. The State Theater served as a community-gathering place featuring shows, orchestras, and, of course, movies. Each Saturday night, the theater screened a current film to a packed crowd. In the next few years, the overwhelming popularity and success of movies in Bogalusa allowed the Berenson family to purchase two more movie houses. They even owned a 9-hole golf course where mill workers relaxed on their days off. In the 1920s, they took in four young orphaned nieces and nephews, the Kayman siblings, who had just come over from Poland. While sisters Sylvia and Jeanette Kayman later moved to New Orleans, their brothers Sidney and Alfred remained in Bogalusa, and worked as clerks at the family department store before opening their own retail businesses.

In 1945, Elias Berenson retired and the department store became known simply as Berenson’s, featuring men’s and women’s clothing, shoes, and dry goods. While this hometown department store closed several years ago, its building is still standing with the Berenson name printed neatly on the façade.

Shortly after the Great Southern Lumber Company founded its mill in 1906, Jews such as Polish immigrant Meyer Berenson arrived in Bogalusa to make their fortunes. Meyer came to Bogalusa at the age of 16 and shortly after opened a store with a fellow Jew. The store did not prove to be a success, so when his brother Elias arrived several years later, they opened Berenson Brothers department store on Columbia Road. This store thrived as Bogalusa experienced a massive influx of mill workers and, in turn, the Berenson family acquired a great deal of wealth.

In 1929, the Berenson family built a large theater in downtown Bogalusa. The State Theater served as a community-gathering place featuring shows, orchestras, and, of course, movies. Each Saturday night, the theater screened a current film to a packed crowd. In the next few years, the overwhelming popularity and success of movies in Bogalusa allowed the Berenson family to purchase two more movie houses. They even owned a 9-hole golf course where mill workers relaxed on their days off. In the 1920s, they took in four young orphaned nieces and nephews, the Kayman siblings, who had just come over from Poland. While sisters Sylvia and Jeanette Kayman later moved to New Orleans, their brothers Sidney and Alfred remained in Bogalusa, and worked as clerks at the family department store before opening their own retail businesses.

In 1945, Elias Berenson retired and the department store became known simply as Berenson’s, featuring men’s and women’s clothing, shoes, and dry goods. While this hometown department store closed several years ago, its building is still standing with the Berenson name printed neatly on the façade.

Jewish Businesses in Bogalusa

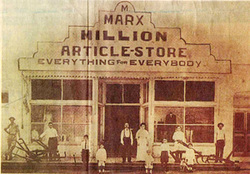

Several other Jewish-owned businesses were located in downtown Bogalusa. Abraham Goldman, a Polish immigrant who came to Bogalusa from New Orleans, opened a department store adjacent to Berenson’s. To avoid fierce competition with their neighbor, Goldman’s specialized in ready-to-wear clothing, with a special emphasis on perfumes and ladies’ clothing. On the other side of Berenson’s department store was M. Marx Sons, a hardware store. Max Marx, a Russian immigrant who had been operating a store in New Orleans, arrived in Bogalusa soon after the opening of the sawmill and set up his family-run store. David Marx, Max’s son, remembered that his father’s store “had anything for anybody! It was a million-article store.” Other stores along Columbia Street included Cohen’s, a furniture store run by two Cohen brothers, and Greenburg’s, a drug store operated by Russian immigrant Henry Greenberg. On the eve of World War II, many of the businesses along Bogalusa’s main strip were owned and operated by Jews. These included The Hollywood shoe store, owned by Alfred Kayman, and Kayman's clothing store, owned by his brother Sidney.

Several other Jewish-owned businesses were located in downtown Bogalusa. Abraham Goldman, a Polish immigrant who came to Bogalusa from New Orleans, opened a department store adjacent to Berenson’s. To avoid fierce competition with their neighbor, Goldman’s specialized in ready-to-wear clothing, with a special emphasis on perfumes and ladies’ clothing. On the other side of Berenson’s department store was M. Marx Sons, a hardware store. Max Marx, a Russian immigrant who had been operating a store in New Orleans, arrived in Bogalusa soon after the opening of the sawmill and set up his family-run store. David Marx, Max’s son, remembered that his father’s store “had anything for anybody! It was a million-article store.” Other stores along Columbia Street included Cohen’s, a furniture store run by two Cohen brothers, and Greenburg’s, a drug store operated by Russian immigrant Henry Greenberg. On the eve of World War II, many of the businesses along Bogalusa’s main strip were owned and operated by Jews. These included The Hollywood shoe store, owned by Alfred Kayman, and Kayman's clothing store, owned by his brother Sidney.

|

|

Multimedia: Sara Stone, daughter of Eva and Meyer Berenson, talks about her family's experiences in Bogalusa, Lousiana. |

Organized Jewish Life in Bogalusa

These families did not wait long after their arrival in Bogalusa to establish a congregation. William Henry Sullivan, the town’s first mayor and resident manager of the sawmill, donated some of the Great Southern Lumber Company’s land to the Jewish families in 1920 to build a synagogue. Two years later, the charter members of Congregation Beth El assembled in the home of Morris Berenson and began to raise funds to construct a temple on the donated land. A brick building with seating for 160 went up over the next year and on a cold February day in 1925, the Jewish community gathered in the sanctuary for the temple’s dedication. At the dedication, Rabbis Max Heller, Moses H. Goldberg, Mendel Silber, and H. Raphael Gold gave speeches, all renowned leaders from various congregations in New Orleans. Visiting rabbis officiated on High Holidays and the occasional Shabbat for the next twenty-five years of Beth El’s existence; no full-time rabbi ever served the congregation. Occasionally, Jewish merchants would gather informally for yahrzeit minyans in the back of someone’s store.

Beth El was traditional in its worship, and unlike many other small-town Jewish congregations, never joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, the national organization of Reform Judaism. By 1940, the congregation boasted a membership of 90 people under the leadership of congregation president Abraham Goldman. Members sponsored a religious school where children were taught Hebrew by Abraham Hershberg of New Orleans. The Beth El Sisterhood became a member unit of the national Hadassah, reflecting the Zionist sentiment of Bogalusa Jews. Organized soon after the first assembly of the congregation and under the leadership of Fay Berenson, the Sisterhood was “active in the charitable work of the congregation.”

These families did not wait long after their arrival in Bogalusa to establish a congregation. William Henry Sullivan, the town’s first mayor and resident manager of the sawmill, donated some of the Great Southern Lumber Company’s land to the Jewish families in 1920 to build a synagogue. Two years later, the charter members of Congregation Beth El assembled in the home of Morris Berenson and began to raise funds to construct a temple on the donated land. A brick building with seating for 160 went up over the next year and on a cold February day in 1925, the Jewish community gathered in the sanctuary for the temple’s dedication. At the dedication, Rabbis Max Heller, Moses H. Goldberg, Mendel Silber, and H. Raphael Gold gave speeches, all renowned leaders from various congregations in New Orleans. Visiting rabbis officiated on High Holidays and the occasional Shabbat for the next twenty-five years of Beth El’s existence; no full-time rabbi ever served the congregation. Occasionally, Jewish merchants would gather informally for yahrzeit minyans in the back of someone’s store.

Beth El was traditional in its worship, and unlike many other small-town Jewish congregations, never joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, the national organization of Reform Judaism. By 1940, the congregation boasted a membership of 90 people under the leadership of congregation president Abraham Goldman. Members sponsored a religious school where children were taught Hebrew by Abraham Hershberg of New Orleans. The Beth El Sisterhood became a member unit of the national Hadassah, reflecting the Zionist sentiment of Bogalusa Jews. Organized soon after the first assembly of the congregation and under the leadership of Fay Berenson, the Sisterhood was “active in the charitable work of the congregation.”

Changes in the Community

The Great Southern Lumber Company closed its doors in 1938, but was soon replaced by Gaylord Container Company, the first in a succession of companies to operate a paper mill and chemical plant at the site of the former lumber mill. Though the paper mill employed thousands of local residents at its post-war peak, changes in ownership and repeated workforce reductions have taken a toll on the local economy. Many Jews left for greater opportunities in Shreveport, New Orleans, and other major cities. While some families stayed, especially those who operated major businesses along Columbia Road, the Jewish community went into decline. Congregation Beth El became largely inactive in the 1950s. The remaining Jewish families occasionally met in the temple, which they sustained until the end of the 20th century, when the land and building were transferred back to the city. Today, the temple building belongs to the Washington Economic Development Foundation, a parish-wide organization. Few modifications have been made to the building. The stained glass Star of David, which dates back to the temple’s construction in the 1920s, still fills the sanctuary with a warm spectrum of colored light beaming in from Georgia Avenue.

The Great Southern Lumber Company closed its doors in 1938, but was soon replaced by Gaylord Container Company, the first in a succession of companies to operate a paper mill and chemical plant at the site of the former lumber mill. Though the paper mill employed thousands of local residents at its post-war peak, changes in ownership and repeated workforce reductions have taken a toll on the local economy. Many Jews left for greater opportunities in Shreveport, New Orleans, and other major cities. While some families stayed, especially those who operated major businesses along Columbia Road, the Jewish community went into decline. Congregation Beth El became largely inactive in the 1950s. The remaining Jewish families occasionally met in the temple, which they sustained until the end of the 20th century, when the land and building were transferred back to the city. Today, the temple building belongs to the Washington Economic Development Foundation, a parish-wide organization. Few modifications have been made to the building. The stained glass Star of David, which dates back to the temple’s construction in the 1920s, still fills the sanctuary with a warm spectrum of colored light beaming in from Georgia Avenue.

Growing Up Jewish in Bogalusa

Those who grew up Jewish in Bogalusa experienced occasional anti-Semitism, but they also earned respect and acceptance among their peers and were often counted among the top students in their schools. Gerald Berenson, like most Bogalusa Jews, grew up in what came to be known as “Jewtown,” the area of Bogalusa north of the Jewish-owned stores on Columbia Street. As a schoolboy, children bullied him and called him and his Jewish friends “Jewboys.” After getting in a fight, however, Gerald learned how to box and joined his high school’s football team; no one picked on him afterward. Berenson became a cardiologist and professor of medicine at the Tulane School of Medicine in New Orleans. Though he moved to New Orleans to pursue his career, he never forgot his childhood in Bogalusa. Dr. Berenson studied the health of Bogalusa residents for decades as the principal investigator for the Bogalusa Heart Study, an internationally renowned study of the early natural history of heart disease.

Those who grew up Jewish in Bogalusa experienced occasional anti-Semitism, but they also earned respect and acceptance among their peers and were often counted among the top students in their schools. Gerald Berenson, like most Bogalusa Jews, grew up in what came to be known as “Jewtown,” the area of Bogalusa north of the Jewish-owned stores on Columbia Street. As a schoolboy, children bullied him and called him and his Jewish friends “Jewboys.” After getting in a fight, however, Gerald learned how to box and joined his high school’s football team; no one picked on him afterward. Berenson became a cardiologist and professor of medicine at the Tulane School of Medicine in New Orleans. Though he moved to New Orleans to pursue his career, he never forgot his childhood in Bogalusa. Dr. Berenson studied the health of Bogalusa residents for decades as the principal investigator for the Bogalusa Heart Study, an internationally renowned study of the early natural history of heart disease.

The Civil Rights Era

The differences between non-Jews and Jews were exacerbated during the 1960s civil rights movement. Jewish civil rights workers from the North started to target Jewish-owned stores in Bogalusa, appealing to the recent history of the Holocaust to convince the merchants to integrate their stores. Like many other Southern Jews, members of the Bogalusa Jewish community were ambivalent about the civil rights movement, and most of all sought to avoid confrontations over the issue. Yet the involvement of many Jews in the nationwide movement, as well as progressive stances taken by a few Jewish locals, drew the attention of extremist groups to Bogalusa Jews. Wally Rosenblum, a Bogalusa native and son of the owner of a department store, remembers when the Ku Klux Klan burned a cross on his front lawn and his family received anti-Semitic hate mail. At the same time, boycotts and picket lines organized by civil rights activists deterred area residents from shopping on Columbia Road.

The differences between non-Jews and Jews were exacerbated during the 1960s civil rights movement. Jewish civil rights workers from the North started to target Jewish-owned stores in Bogalusa, appealing to the recent history of the Holocaust to convince the merchants to integrate their stores. Like many other Southern Jews, members of the Bogalusa Jewish community were ambivalent about the civil rights movement, and most of all sought to avoid confrontations over the issue. Yet the involvement of many Jews in the nationwide movement, as well as progressive stances taken by a few Jewish locals, drew the attention of extremist groups to Bogalusa Jews. Wally Rosenblum, a Bogalusa native and son of the owner of a department store, remembers when the Ku Klux Klan burned a cross on his front lawn and his family received anti-Semitic hate mail. At the same time, boycotts and picket lines organized by civil rights activists deterred area residents from shopping on Columbia Road.

The Jewish Community in Bogalusa Today

The events of the civil rights era combined with a general economic decline to spell the end of Jewish retail in Bogalusa. Though the paper mill employed thousands of area residents during its postwar peak, that number has dropped to around one thousand. The city's population is also down, decreasing from nearly 17,000 in 1980 to just more than 13,000 in 2000. Despite the efforts of city leaders, including civically minded Jewish businessmen, new industries have not elected to move to Bogalusa.

Few remnants of Jewish life in Bogalusa exist today. Only a handful of Jewish families still live in the city and there is no Jewish cemetery to pay tribute to the hard work of families such as the Berensons, Goldmans, Cohens, Marxs, and Greenburgs. By 2000, Wally Rosenblum had closed the small department store his father, Alvin, founded in 1954 and relocated to Mandeville. Rosenblum's was the the last Jewish-owned retail operation in Bogalusa. Despite the anti-Semitism his family endured during the civil rights era and subsequent struggles to reinvigorate the city's economy, he takes pride in his family’s presence in Bogalusa: “Through the years, my family and other Jewish families have given people here a better understanding of what it means to be Jewish, that a Jewish person can be normal just like them, not have horns, can love and be loved.”

Few remnants of Jewish life in Bogalusa exist today. Only a handful of Jewish families still live in the city and there is no Jewish cemetery to pay tribute to the hard work of families such as the Berensons, Goldmans, Cohens, Marxs, and Greenburgs. By 2000, Wally Rosenblum had closed the small department store his father, Alvin, founded in 1954 and relocated to Mandeville. Rosenblum's was the the last Jewish-owned retail operation in Bogalusa. Despite the anti-Semitism his family endured during the civil rights era and subsequent struggles to reinvigorate the city's economy, he takes pride in his family’s presence in Bogalusa: “Through the years, my family and other Jewish families have given people here a better understanding of what it means to be Jewish, that a Jewish person can be normal just like them, not have horns, can love and be loved.”