Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Baton Rouge: Historical Overview

|

Baton Rouge’s Jewish community has mirrored the development of Louisiana’s capital city itself. During the 19th century, Baton Rouge was a small town that was chosen as the state’s capital in 1846 precisely because it was located in the hinterlands, upriver from the commercial and cultural center of New Orleans. In the 20th century, Baton Rouge has emerged as a major industrial center and port. Coupled with its status as the capital and home of the state university, Baton Rouge has flourished in recent decades, as has its Jewish community. In contrast to many other Jewish communities in Louisiana, Baton Rouge’s Jewish population has grown significantly since World War II and has remained steady in recent years.

|

Stories of the Jewish Community in Baton Rouge

Early Settlers

Jews have lived in the Baton Rouge area since the colonial era. The first Jew to settle in the area was Isaac Henriques Fastio, who was born in Bordeaux, France. He came to Louisiana from Curacao by 1766, originally settling in New Orleans. Fastio became a business partner of Isaac Monsanto, who is considered to be the first Jew to settle in New Orleans. Fastio later moved to Point Coupee (north of present day Baton Rouge) and opened a trading business, remaining in the area for fifty years. By 1780, Benjamin Monsanto, Isaac’s brother, had joined Fastio in Point Coupee as the two became business partners. Monsanto purchased a plantation and slaves, but found it difficult to become a successful planter. He moved to Natchez by 1788, becoming the first Jew to settle in Mississippi. According to French colonial law, Jews were not allowed to live in Louisiana, though this prohibition was not rigidly enforced. After Spain took possession of Louisiana, the new colonial governor expelled Jews from New Orleans in 1769, but Fastio remained in Point Coupee. Either he was unknown to the new governor, or was not seen as any kind of economic threat due to his remote location.

One of the earliest Jews to live in Baton Rouge was Maurice Barnett, who had moved to the colonial outpost by 1806 when it was part of Spanish West Florida. Born in Amsterdam, Barnett became a general merchant in Baton Rouge, selling food, liquor, dry goods, furniture, hardware, and other products he received from wholesale houses in New Orleans. Since cash was scarce in this far-flung corner of the Spanish empire, most of his business was on the barter system. Although he was Jewish, Barnett was a respected citizen in Baton Rouge. The colonial governor appointed him as head of a posse to catch three armed robbers who had struck in the area. Barnett led a group of four slaves and another white man and quickly captured the three scoundrels. Barnett’s tenure in Baton Rouge did not last long; by 1812, he had moved to New Orleans in search of greater economic opportunity.

Jews have lived in the Baton Rouge area since the colonial era. The first Jew to settle in the area was Isaac Henriques Fastio, who was born in Bordeaux, France. He came to Louisiana from Curacao by 1766, originally settling in New Orleans. Fastio became a business partner of Isaac Monsanto, who is considered to be the first Jew to settle in New Orleans. Fastio later moved to Point Coupee (north of present day Baton Rouge) and opened a trading business, remaining in the area for fifty years. By 1780, Benjamin Monsanto, Isaac’s brother, had joined Fastio in Point Coupee as the two became business partners. Monsanto purchased a plantation and slaves, but found it difficult to become a successful planter. He moved to Natchez by 1788, becoming the first Jew to settle in Mississippi. According to French colonial law, Jews were not allowed to live in Louisiana, though this prohibition was not rigidly enforced. After Spain took possession of Louisiana, the new colonial governor expelled Jews from New Orleans in 1769, but Fastio remained in Point Coupee. Either he was unknown to the new governor, or was not seen as any kind of economic threat due to his remote location.

One of the earliest Jews to live in Baton Rouge was Maurice Barnett, who had moved to the colonial outpost by 1806 when it was part of Spanish West Florida. Born in Amsterdam, Barnett became a general merchant in Baton Rouge, selling food, liquor, dry goods, furniture, hardware, and other products he received from wholesale houses in New Orleans. Since cash was scarce in this far-flung corner of the Spanish empire, most of his business was on the barter system. Although he was Jewish, Barnett was a respected citizen in Baton Rouge. The colonial governor appointed him as head of a posse to catch three armed robbers who had struck in the area. Barnett led a group of four slaves and another white man and quickly captured the three scoundrels. Barnett’s tenure in Baton Rouge did not last long; by 1812, he had moved to New Orleans in search of greater economic opportunity.

Organized Jewish Life in Baton Rouge

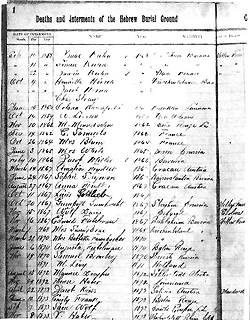

Men like Isaac Fastio and Maurice Barnett were exceptional cases. Baton Rouge did not develop what can be recognized as a Jewish community until the mid-19th century, when Jewish immigrants from Alsace and the German states settled in the small city upriver from the port of New Orleans. The Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1858 forced the small Jewish community of Baton Rouge to establish its first institution, a cemetery association that acquired land in order to bury the six Jews who had died from the disease. A year later, this small group of Baton Rouge Jews established the “Hebrew Congregation of the City of Baton Rouge.” The congregation’s founding members were Jacob Farnbacher, Leopold Rosenthal, A. Mann, Nathan Dalsheimer, Charles Simon, Simon Bear, Leopold Dalsheimer, and Simon Mendelsohn. All of the founders were foreign-born, from either Bavaria or Alsace. The group met initially in the upstairs of the Singletary Building at the corner of Florida and Church streets, though soon after forming, they purchased land for the future construction of a synagogue.

The congregation’s plans were put on hold during the Civil War as many of its members scattered. Baton Rouge was occupied by the Union Army during most of the war, and the fledgling Jewish congregation ceased meeting during the conflict. In 1868, the group reorganized under the name “Shaare Chessed” (Gates of Mercy), and began to meet in Dalsheimer Hall, a community gathering space for speeches, dances, and other events, that was owned by one of the founding members of the congregation. The members no longer liked the location of the land they had originally bought in 1859, and decided to trade it with the local Catholic Church for another lot on 5th and Laurel Streets that already contained a former school building. On March 16, 1877, Shaare Chessed dedicated this building as its first synagogue with a ceremony that attracted city officials and many non-Jews. Under the leadership of Rabbi Isadore Lewinhall, the congregation moved away from its Orthodox roots in 1879 when they officially adopted Isaac Mayer Wise’s Minhag America as their prayer book.

Just as the congregation was settling into its new synagogue, there was a dispute over who had legal title to the property. The fight went all the way to the Louisiana Supreme Court, which ultimately decided against Shaare Chessed. The congregation was forced out of their building in 1883. They moved all of their furnishings to Dalsheimer Hall, where they met for the next few years. In 1885, they reincorporated, changing their name to “B’nai Israel” and repurchased their old red brick building, which had been constructed before the Civil War.

A key force in the congregation’s effort to acquire a synagogue was the Ladies Hebrew Association of Baton Rouge, which had been organized by seventeen women in 1871. The group’s expressed purpose was to raise money for a permanent home for the congregation. They held balls, cake raffles, and other events that raised money for the building fund. Their efforts helped to pay off the mortgage on the property the congregation had bought in 1859. After Shaare Chessed acquired its building in 1877, the Ladies Hebrew Association raised $1400 to pay for its furnishings, including an organ, Torah covers, and an eternal light. Once the synagogue was dedicated, the association dissolved. After the congregation was evicted from the building, the Ladies Hebrew Association reorganized and set about raising money to reacquire their temple. Once again, they held a series of successful fundraising balls, and were able to help pay off the debt on the building. After the congregation had resettled in its old home, the group decided to expand its mission, caring for the cemetery, running the religious school, and raising money for charity. In 1914, they changed their name to the B’nai Israel Sisterhood, and continued their indispensable work for the congregation.

Jewish men also founded an organization of their own, establishing a local chapter of the B’nai B’rith in 1875. Originally, the group met at Dalsheimer hall, but later met at the synagogue.

Men like Isaac Fastio and Maurice Barnett were exceptional cases. Baton Rouge did not develop what can be recognized as a Jewish community until the mid-19th century, when Jewish immigrants from Alsace and the German states settled in the small city upriver from the port of New Orleans. The Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1858 forced the small Jewish community of Baton Rouge to establish its first institution, a cemetery association that acquired land in order to bury the six Jews who had died from the disease. A year later, this small group of Baton Rouge Jews established the “Hebrew Congregation of the City of Baton Rouge.” The congregation’s founding members were Jacob Farnbacher, Leopold Rosenthal, A. Mann, Nathan Dalsheimer, Charles Simon, Simon Bear, Leopold Dalsheimer, and Simon Mendelsohn. All of the founders were foreign-born, from either Bavaria or Alsace. The group met initially in the upstairs of the Singletary Building at the corner of Florida and Church streets, though soon after forming, they purchased land for the future construction of a synagogue.

The congregation’s plans were put on hold during the Civil War as many of its members scattered. Baton Rouge was occupied by the Union Army during most of the war, and the fledgling Jewish congregation ceased meeting during the conflict. In 1868, the group reorganized under the name “Shaare Chessed” (Gates of Mercy), and began to meet in Dalsheimer Hall, a community gathering space for speeches, dances, and other events, that was owned by one of the founding members of the congregation. The members no longer liked the location of the land they had originally bought in 1859, and decided to trade it with the local Catholic Church for another lot on 5th and Laurel Streets that already contained a former school building. On March 16, 1877, Shaare Chessed dedicated this building as its first synagogue with a ceremony that attracted city officials and many non-Jews. Under the leadership of Rabbi Isadore Lewinhall, the congregation moved away from its Orthodox roots in 1879 when they officially adopted Isaac Mayer Wise’s Minhag America as their prayer book.

Just as the congregation was settling into its new synagogue, there was a dispute over who had legal title to the property. The fight went all the way to the Louisiana Supreme Court, which ultimately decided against Shaare Chessed. The congregation was forced out of their building in 1883. They moved all of their furnishings to Dalsheimer Hall, where they met for the next few years. In 1885, they reincorporated, changing their name to “B’nai Israel” and repurchased their old red brick building, which had been constructed before the Civil War.

A key force in the congregation’s effort to acquire a synagogue was the Ladies Hebrew Association of Baton Rouge, which had been organized by seventeen women in 1871. The group’s expressed purpose was to raise money for a permanent home for the congregation. They held balls, cake raffles, and other events that raised money for the building fund. Their efforts helped to pay off the mortgage on the property the congregation had bought in 1859. After Shaare Chessed acquired its building in 1877, the Ladies Hebrew Association raised $1400 to pay for its furnishings, including an organ, Torah covers, and an eternal light. Once the synagogue was dedicated, the association dissolved. After the congregation was evicted from the building, the Ladies Hebrew Association reorganized and set about raising money to reacquire their temple. Once again, they held a series of successful fundraising balls, and were able to help pay off the debt on the building. After the congregation had resettled in its old home, the group decided to expand its mission, caring for the cemetery, running the religious school, and raising money for charity. In 1914, they changed their name to the B’nai Israel Sisterhood, and continued their indispensable work for the congregation.

Jewish men also founded an organization of their own, establishing a local chapter of the B’nai B’rith in 1875. Originally, the group met at Dalsheimer hall, but later met at the synagogue.

Jewish Businesses in Baton Rouge

Most members of B’nai Israel were immigrants from France or Germany who established retail businesses in Baton Rouge. According to a 1905 history of Jews in Louisiana, in Baton Rouge, “the Jewish element of the population has a strong hold, not only upon the business of the place but of planting interests in all the surrounding country.” Jacob Farnbacher was born in Bavaria, and came to the United States in 1857, when he was thirty years old. He soon established a dry goods store in Baton Rouge, which became quite successful after the Civil War. By 1870, Farnbacher was already worth over $5000 in real estate and personal property. By the early 20th century, he had diversified his holdings, becoming the director of a local insurance company and the co-owner of a local bank. His son, Solon, joined his father in the family business, and became an active member of several local fraternal organizations and a director of the Louisiana State Bank.

Simon Mendelsohn came from Alsace-Lorraine to Baton Rouge in the mid 19th century. He was drawn to Baton Rouge by the strong French culture of the region. By the time of the Civil War, Mendelsohn owned a grocery store in town. While his home was burned by the Union Army and his family had to flee to the countryside, Mendelsohn returned after the war, and reestablished his business, sinking deep roots into the community. Even after his death in 1889, his family remained an important part of the local economy and society. His wife Sophie was active on the board of the local Protestant Orphan’s Home, and arranged for the orphans to have a party each year on a ferry boat owned by her son. Ben Mayer came to Baton Rouge from Natchez and married Simon and Sophie’s daughter Zerlina. Mayer owned a wholesale grocery business as well as a brickyard. Mayer became a very prominent civic leader, serving on the city council for many years. Abe Rosenfield, the brother of Sophie Mendelsohn, owned the largest dry goods store in Baton Rouge in the early 20th century. Rosenfield lived with his family in New Orleans, but would come to Baton Rouge during the week, staying with his sister Sophie, and return home for the weekends. Rosenfield’s weekly commute shows how Baton Rouge was still a provincial outpost for the regional economic hub of New Orleans.

Most members of B’nai Israel were immigrants from France or Germany who established retail businesses in Baton Rouge. According to a 1905 history of Jews in Louisiana, in Baton Rouge, “the Jewish element of the population has a strong hold, not only upon the business of the place but of planting interests in all the surrounding country.” Jacob Farnbacher was born in Bavaria, and came to the United States in 1857, when he was thirty years old. He soon established a dry goods store in Baton Rouge, which became quite successful after the Civil War. By 1870, Farnbacher was already worth over $5000 in real estate and personal property. By the early 20th century, he had diversified his holdings, becoming the director of a local insurance company and the co-owner of a local bank. His son, Solon, joined his father in the family business, and became an active member of several local fraternal organizations and a director of the Louisiana State Bank.

Simon Mendelsohn came from Alsace-Lorraine to Baton Rouge in the mid 19th century. He was drawn to Baton Rouge by the strong French culture of the region. By the time of the Civil War, Mendelsohn owned a grocery store in town. While his home was burned by the Union Army and his family had to flee to the countryside, Mendelsohn returned after the war, and reestablished his business, sinking deep roots into the community. Even after his death in 1889, his family remained an important part of the local economy and society. His wife Sophie was active on the board of the local Protestant Orphan’s Home, and arranged for the orphans to have a party each year on a ferry boat owned by her son. Ben Mayer came to Baton Rouge from Natchez and married Simon and Sophie’s daughter Zerlina. Mayer owned a wholesale grocery business as well as a brickyard. Mayer became a very prominent civic leader, serving on the city council for many years. Abe Rosenfield, the brother of Sophie Mendelsohn, owned the largest dry goods store in Baton Rouge in the early 20th century. Rosenfield lived with his family in New Orleans, but would come to Baton Rouge during the week, staying with his sister Sophie, and return home for the weekends. Rosenfield’s weekly commute shows how Baton Rouge was still a provincial outpost for the regional economic hub of New Orleans.

Temple B'nai Israel and a Schism

This growth in Baton Rouge’s Jewish community was reflected in Temple B’nai Israel. After having financial troubles during its early decades, the congregation began to expand, adding a social hall to their building in 1920. They also enjoyed greater stability in rabbinic leadership. Rabbi Max Klein had led the congregation from 1886 to 1900. Rabbi Frank Rosenthal served both B’nai Israel and Temple Sinai in nearby St. Francisville from 1901 to 1911. During the next 16 years, four different rabbis led the congregation. There were times when the congregation did not have a rabbi, and members served as lay readers. In 1927, Rabbi Walter Peiser came to Baton Rouge, and remained the spiritual leader of B’nai Israel for almost 40 years, retiring in 1966.

Peiser was a man of strong principle who refused to say an invocation to the state legislature in 1929 in protest of Governor Huey Long’s political corruption. Peiser explained to Time Magazine that his prayers would have been “coarsened and cheapened…by a Chief Executive…unworthy of high office.”

Peiser was a strong adherent of classical Reform Judaism, and was a good fit for B’nai Israel, which used primarily English in their services and employed a non-Jewish organist and soloist. W.B. Clark was their longtime organist, who for a while even blew shofar on the High Holidays. Members of B’nai Israel took great pride in being integrated with the larger community. In the commemorative booklet they printed for their 100th anniversary, they proclaimed, “the congregation has always felt itself to be a part of, rather than apart from, the Baton Rouge community.” B’nai Israel held an open house for their non-Jewish friends as part of their centennial celebration.

Both Peiser and many of his congregants were anti-Zionists, rejecting the idea that Jews were a separate people who needed their own homeland. They joined the American Council for Judaism, which opposed the creation of a Jewish state, and stressed that Jews were simply a religious group. Rabbi Peiser and the leadership of the congregation viewed with concern the growing movement to establish the state of Israel as well as the increasing support for Zionism amongst the national leadership of Reform Judaism. On April 25, 1945, Rabbi Peiser and the president of B’nai Israel sent a letter to every congregant, stating “our congregation affirms its adherence to the principles of American Judaism; denies the right of Zionists to speak for it…Our nation is America and our religion is Judaism.” These ideas, which came from the 1885 Pittsburgh Platform, the foundation of Classical Reform Judaism, were written into the constitution of B’nai Israel in 1945. All rabbis, officers, and trustees of B’nai Israel now had to pledge to support these ideals.

This new requirement for congregational leadership set off a firestorm of controversy. The dispute was very reminiscent of the 1943 conflict within Temple Beth Israel in Houston, which led to a split in Texas’ oldest congregation. B’nai Israel also suffered a schism. In response to the board’s actions, twenty families left B’nai Israel and began to hold services on their own. Those who left were more likely to be from Orthodox or Conservative backgrounds and to be relative newcomers to Baton Rouge, though the breakaway group also included several “old-timers.” On August 17, 1945, 29 families signed a charter for a new congregation they named “Liberal Synagogue.” Their name signified that the congregation would Beth Shalom be tolerant of different ideas and practices. From the start, Liberal Synagogue differentiated itself from B’nai Israel by allowing kippot (head coverings) and tallit (prayer shawls) and introducing the bar mitzvah ritual, although they also affiliated with the Reform Movement. Lewis Botnick was chosen as its first president. Later, the group changed its name to Beth Shalom. Initially, Liberal Synagogue worshiped in a building on the Acadian Thruway. In 1980, they built their current home on Jefferson Highway.

This growth in Baton Rouge’s Jewish community was reflected in Temple B’nai Israel. After having financial troubles during its early decades, the congregation began to expand, adding a social hall to their building in 1920. They also enjoyed greater stability in rabbinic leadership. Rabbi Max Klein had led the congregation from 1886 to 1900. Rabbi Frank Rosenthal served both B’nai Israel and Temple Sinai in nearby St. Francisville from 1901 to 1911. During the next 16 years, four different rabbis led the congregation. There were times when the congregation did not have a rabbi, and members served as lay readers. In 1927, Rabbi Walter Peiser came to Baton Rouge, and remained the spiritual leader of B’nai Israel for almost 40 years, retiring in 1966.

Peiser was a man of strong principle who refused to say an invocation to the state legislature in 1929 in protest of Governor Huey Long’s political corruption. Peiser explained to Time Magazine that his prayers would have been “coarsened and cheapened…by a Chief Executive…unworthy of high office.”

Peiser was a strong adherent of classical Reform Judaism, and was a good fit for B’nai Israel, which used primarily English in their services and employed a non-Jewish organist and soloist. W.B. Clark was their longtime organist, who for a while even blew shofar on the High Holidays. Members of B’nai Israel took great pride in being integrated with the larger community. In the commemorative booklet they printed for their 100th anniversary, they proclaimed, “the congregation has always felt itself to be a part of, rather than apart from, the Baton Rouge community.” B’nai Israel held an open house for their non-Jewish friends as part of their centennial celebration.

Both Peiser and many of his congregants were anti-Zionists, rejecting the idea that Jews were a separate people who needed their own homeland. They joined the American Council for Judaism, which opposed the creation of a Jewish state, and stressed that Jews were simply a religious group. Rabbi Peiser and the leadership of the congregation viewed with concern the growing movement to establish the state of Israel as well as the increasing support for Zionism amongst the national leadership of Reform Judaism. On April 25, 1945, Rabbi Peiser and the president of B’nai Israel sent a letter to every congregant, stating “our congregation affirms its adherence to the principles of American Judaism; denies the right of Zionists to speak for it…Our nation is America and our religion is Judaism.” These ideas, which came from the 1885 Pittsburgh Platform, the foundation of Classical Reform Judaism, were written into the constitution of B’nai Israel in 1945. All rabbis, officers, and trustees of B’nai Israel now had to pledge to support these ideals.

This new requirement for congregational leadership set off a firestorm of controversy. The dispute was very reminiscent of the 1943 conflict within Temple Beth Israel in Houston, which led to a split in Texas’ oldest congregation. B’nai Israel also suffered a schism. In response to the board’s actions, twenty families left B’nai Israel and began to hold services on their own. Those who left were more likely to be from Orthodox or Conservative backgrounds and to be relative newcomers to Baton Rouge, though the breakaway group also included several “old-timers.” On August 17, 1945, 29 families signed a charter for a new congregation they named “Liberal Synagogue.” Their name signified that the congregation would Beth Shalom be tolerant of different ideas and practices. From the start, Liberal Synagogue differentiated itself from B’nai Israel by allowing kippot (head coverings) and tallit (prayer shawls) and introducing the bar mitzvah ritual, although they also affiliated with the Reform Movement. Lewis Botnick was chosen as its first president. Later, the group changed its name to Beth Shalom. Initially, Liberal Synagogue worshiped in a building on the Acadian Thruway. In 1980, they built their current home on Jefferson Highway.

B’nai Israel remained in its downtown synagogue until 1954, when they moved to a new building at the corner of Parker and Kleinert Streets. When Rabbi Peiser retired in 1966, Lester Roubey filled the pulpit for the next fourteen years. Rabbi Barry Weinstein served B’nai Israel from 1983 to 2007, when he was replaced by Corie Yutkin, the congregation’s first female rabbi. After the split in 1945, B’nai Israel remained entrenched within Classical Reform Judaism and anti-Zionism. In 1967, the leadership of B’nai Israel would not allow members to use the temple for a fundraising event for Israel. Over the years, B’nai Israel has changed, largely through the leadership of Rabbi Weinstein, adopting more traditional practices and dropping its hostility toward Zionism.

Beth Shalom started out as a small group of dissidents, but soon grew into a strong, viable congregation with a synagogue and a full-time rabbi, although it has always been smaller than B’nai Israel. In 1962, they had 96 member families, and continued to grow along with Baton Rouge’s Jewish community. By 1990, they had 184 members. Beth Shalom has been led by a series of rabbis; currently, Rabbi Natan Trief is its spiritual leader.

1945 remains a key year in the history of the Baton Rouge Jewish community as the schism remains to this day. Baton Rouge is home to two different congregations, both Reform, and both small. In 2007, B’nai Israel had 214 members, while Beth Shalom had 128. Efforts to join the two congregations have failed due to lingering resentments and refusals to compromise. The rivalry between the two congregations still divides the Baton Rouge Jewish community today.

Beth Shalom started out as a small group of dissidents, but soon grew into a strong, viable congregation with a synagogue and a full-time rabbi, although it has always been smaller than B’nai Israel. In 1962, they had 96 member families, and continued to grow along with Baton Rouge’s Jewish community. By 1990, they had 184 members. Beth Shalom has been led by a series of rabbis; currently, Rabbi Natan Trief is its spiritual leader.

1945 remains a key year in the history of the Baton Rouge Jewish community as the schism remains to this day. Baton Rouge is home to two different congregations, both Reform, and both small. In 2007, B’nai Israel had 214 members, while Beth Shalom had 128. Efforts to join the two congregations have failed due to lingering resentments and refusals to compromise. The rivalry between the two congregations still divides the Baton Rouge Jewish community today.

Working Together

Despite this tension, Baton Rouge Jews have pulled together in times of crisis. After Hurricane Katrina, the small Baton Rouge Jewish Federation, which had only one part-time employee, took in hundreds of refugees from New Orleans, working with national Jewish relief organizations. They also coordinated a rescue operation that pulled stranded people out of the Lakeview section of the city after the levees broke. While most of the Jewish evacuees have left Baton Rouge, others have stayed. The Federation has taken on the responsibility of caring for the economic and emotional well-being of the evacuees. Though they are only a small community, Baton Rouge played a crucial role in the Jewish response to Hurricane Katrina. A month later, the city itself was hit by Hurricane Rita, which severely damaged the sanctuary of Temple Beth Shalom.

Despite this tension, Baton Rouge Jews have pulled together in times of crisis. After Hurricane Katrina, the small Baton Rouge Jewish Federation, which had only one part-time employee, took in hundreds of refugees from New Orleans, working with national Jewish relief organizations. They also coordinated a rescue operation that pulled stranded people out of the Lakeview section of the city after the levees broke. While most of the Jewish evacuees have left Baton Rouge, others have stayed. The Federation has taken on the responsibility of caring for the economic and emotional well-being of the evacuees. Though they are only a small community, Baton Rouge played a crucial role in the Jewish response to Hurricane Katrina. A month later, the city itself was hit by Hurricane Rita, which severely damaged the sanctuary of Temple Beth Shalom.

The Jewish Community in Baton Rouge Today

While the Baton Rouge Jewish community has endured internal conflicts and natural disasters, their future looks bright.