Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - St. Francisville, Louisiana

St. Francisville: Historical Overview

Stories of the Jewish Community in St.. Francisville

Early Settlers

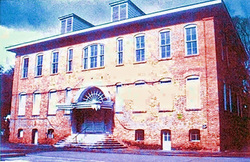

The first Jews in St. Francisville arrived in 1850s, just as the town was growing into a hub for cotton distribution. Upon their arrival in New Orleans, Jewish immigrants from Germany traveled north along the Mississippi River and settled in small towns like St. Francisville. Julius Freyhan was the first such immigrant to arrive. Though not directly involved in the shipping industry, Freyhan took advantage of the expanding opportunities in downtown St. Francisville, uphill from the shipping docks down on the bayou. He opened his own dry goods store called Julius Freyhan & Co., and after serving in the 4th Louisiana Infantry in the Civil War, he started an expansive network of stores, cotton gins and mills, opera houses, and saloons. He also speculated in real estate both in West Feliciana Parish and throughout Louisiana. Although he had by then become quite wealthy, Freyhan assumed various civic responsibilities. He donated generously towards the building of levees and roads in St. Francisville. When Freyhan died in 1904, he bequeathed $8,000 to the town to build its first public school. The school, rebuilt and named Julius Freyhan High School, closed in the early 1950s and is currently being restored for future use as both a community center and a museum.

The first Jews in St. Francisville arrived in 1850s, just as the town was growing into a hub for cotton distribution. Upon their arrival in New Orleans, Jewish immigrants from Germany traveled north along the Mississippi River and settled in small towns like St. Francisville. Julius Freyhan was the first such immigrant to arrive. Though not directly involved in the shipping industry, Freyhan took advantage of the expanding opportunities in downtown St. Francisville, uphill from the shipping docks down on the bayou. He opened his own dry goods store called Julius Freyhan & Co., and after serving in the 4th Louisiana Infantry in the Civil War, he started an expansive network of stores, cotton gins and mills, opera houses, and saloons. He also speculated in real estate both in West Feliciana Parish and throughout Louisiana. Although he had by then become quite wealthy, Freyhan assumed various civic responsibilities. He donated generously towards the building of levees and roads in St. Francisville. When Freyhan died in 1904, he bequeathed $8,000 to the town to build its first public school. The school, rebuilt and named Julius Freyhan High School, closed in the early 1950s and is currently being restored for future use as both a community center and a museum.

Organized Jewish Life in St. Francisville

Although Jews lived in St. Francisville by the 1850s, decades passed before uniquely Jewish institutions came into existence. Julius Freyhan purchased the original plot of land that would become Hebrew Rest Cemetery in 1891. In 1893, a committee of 23 local Jews, chaired by Adolph Teutsch, a grocer who had immigrated from Bavaria 13 years earlier, met to oversee the construction of a synagogue in St. Francisville. It was not until 1901, however, that Temple Sinai incorporated formally under the leadership of Ben Mann, who managed the local livery stable. Soon thereafter the temple inherited the title to the cemetery from Freyhan, hosted a lavish event to attract contributions to the building fund, and at last laid the cornerstone for the future synagogue on a hill overlooking the Mississippi River.

Construction of the temple concluded in January 1903 with a stately dedication, an event “par excellence” where “the sacred building was filled prior to the hour for the services by a large congregation composed of both Jews and Gentiles.” As rabbis and reverends, judges and lawyers, and merchants and farmers gathered for this historic event, the Jewish community strengthened both internally and externally: “It was an hour of rejoicing, and Christian friends, fully sympathetic, rejoiced too.”

Although Jews lived in St. Francisville by the 1850s, decades passed before uniquely Jewish institutions came into existence. Julius Freyhan purchased the original plot of land that would become Hebrew Rest Cemetery in 1891. In 1893, a committee of 23 local Jews, chaired by Adolph Teutsch, a grocer who had immigrated from Bavaria 13 years earlier, met to oversee the construction of a synagogue in St. Francisville. It was not until 1901, however, that Temple Sinai incorporated formally under the leadership of Ben Mann, who managed the local livery stable. Soon thereafter the temple inherited the title to the cemetery from Freyhan, hosted a lavish event to attract contributions to the building fund, and at last laid the cornerstone for the future synagogue on a hill overlooking the Mississippi River.

Construction of the temple concluded in January 1903 with a stately dedication, an event “par excellence” where “the sacred building was filled prior to the hour for the services by a large congregation composed of both Jews and Gentiles.” As rabbis and reverends, judges and lawyers, and merchants and farmers gathered for this historic event, the Jewish community strengthened both internally and externally: “It was an hour of rejoicing, and Christian friends, fully sympathetic, rejoiced too.”

Unfortunately, this memorable dedication of Temple Sinai defined the pinnacle of Jewish life in St. Francisville. It had taken over ten years for the congregation to build a synagogue, yet two major internal issues gave rise to its tragic deterioration. First, the executive board of the congregation had significant difficulties in securing a permanent rabbi. Student rabbis from Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati had come to St. Francisville in earlier years to lead services on High Holidays and the occasional Shabbat.

Attempts to hire a full-time rabbi proved more difficult than anticipated. The congregation hired Rabbi Frank Rosenthal from Congregation B’nai Israel in Baton Rouge as a part-time rabbi. He resigned in September 1904 and several years later left Louisiana entirely to become the longtime rabbi at Congregation B’nai Israel in Columbus, Georgia. In the years following Rabbi Rosenthal’s departure, the congregation made successive yet fruitless attempts to hire rabbis from other congregations in Louisiana, including Rabbi Max Heller of Temple Sinai in New Orleans and Rabbi Marx Klein of Congregation Bikur Cholim in Donaldsonville.

For a short time Rabbi Max Raisin, a recent graduate from Hebrew Union College, served as rabbi; however, he resigned in January 1905 and went on to become a well known leader of the Reform movement. Raisin’s departure marked the end of formal religious leadership in St. Francisville. Membership declined precipitously and by 1920, the congregation no longer held regular services. In a 1917 issue of St. Francisville’s newspaper, the True Democrat, a profile of Temple Sinai mentioned that “the Congregation enjoys on the formal seasons of public worship, required by their faith.” And although Temple Sinai had been meeting more infrequently through the years, “the congregation hardly misses the ministrations of a rabbi.”

Perhaps more importantly, the congregation declined when the generation of Jewish immigrants who arrived in Mississippi in the mid-19th century either moved from St. Francisville or died. Wealthy families sought out more lucrative opportunities in cities such as New Orleans, St. Louis, and New York. These families withdrew their generous patronage of Temple Sinai and, in turn, the congregation could not afford improved facilities, a Sunday school, or the services of a permanent rabbi. A tenacious few remained in St. Francisville beyond the first decades of the 20th century, but their children eventually left. This new generation traded in their life in plantation country for a more urban one.

Migration and irregular religious leadership ultimately spelled the end for Temple Sinai. In 1921, the temple building and its scenic property were sold to the local Presbyterian congregation that would reside there until the end of the 20th century when the historic building was ultimately abandoned. It is not known if Temple Sinai continued to meet informally after the sale of its building, but the only formal meeting of its executive board thereafter took place in 1940. At this meeting, the last surviving members of the temple agreed to sell part of the cemetery property for $200.

The Impact of the Jewish Community in St. Francisville

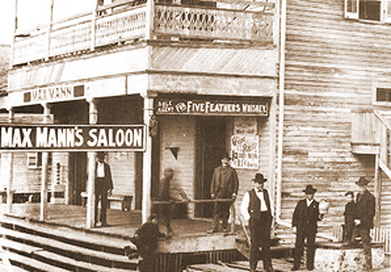

While Jews resided in St. Francisville for only a short time, they maintained a strong presence in civic life. Besides Julius Freyhan and his conglomerate of cotton and dry goods businesses, many Jews owned their own businesses that filled various needs in the community. The Teutsch family ran one of the few grocery stores in town. Morris Burgas owned a very successful dry goods store that offered “competitive prices.” Max Mann, brother of Temple Sinai President Ben Mann, owned one of the most popular bars in the region, right on the Mississippi River where many steamboat passengers stopped for a cold beer or a glass of local whiskey. However, not all Jewish activities in St. Francisville were business ventures. They gave back generously to the community which had given them so much. The Ladies Aid Society, a women’s auxiliary society of Temple Sinai, was organized in 1893 and engaged in humanitarian work throughout Louisiana. In 1908, the Society collected garments from congregants for various charities in West Feliciana Parish and New Orleans under the leadership of Rena Burgas, the wife of Morris Burgas.

Attempts to hire a full-time rabbi proved more difficult than anticipated. The congregation hired Rabbi Frank Rosenthal from Congregation B’nai Israel in Baton Rouge as a part-time rabbi. He resigned in September 1904 and several years later left Louisiana entirely to become the longtime rabbi at Congregation B’nai Israel in Columbus, Georgia. In the years following Rabbi Rosenthal’s departure, the congregation made successive yet fruitless attempts to hire rabbis from other congregations in Louisiana, including Rabbi Max Heller of Temple Sinai in New Orleans and Rabbi Marx Klein of Congregation Bikur Cholim in Donaldsonville.

For a short time Rabbi Max Raisin, a recent graduate from Hebrew Union College, served as rabbi; however, he resigned in January 1905 and went on to become a well known leader of the Reform movement. Raisin’s departure marked the end of formal religious leadership in St. Francisville. Membership declined precipitously and by 1920, the congregation no longer held regular services. In a 1917 issue of St. Francisville’s newspaper, the True Democrat, a profile of Temple Sinai mentioned that “the Congregation enjoys on the formal seasons of public worship, required by their faith.” And although Temple Sinai had been meeting more infrequently through the years, “the congregation hardly misses the ministrations of a rabbi.”

Perhaps more importantly, the congregation declined when the generation of Jewish immigrants who arrived in Mississippi in the mid-19th century either moved from St. Francisville or died. Wealthy families sought out more lucrative opportunities in cities such as New Orleans, St. Louis, and New York. These families withdrew their generous patronage of Temple Sinai and, in turn, the congregation could not afford improved facilities, a Sunday school, or the services of a permanent rabbi. A tenacious few remained in St. Francisville beyond the first decades of the 20th century, but their children eventually left. This new generation traded in their life in plantation country for a more urban one.

Migration and irregular religious leadership ultimately spelled the end for Temple Sinai. In 1921, the temple building and its scenic property were sold to the local Presbyterian congregation that would reside there until the end of the 20th century when the historic building was ultimately abandoned. It is not known if Temple Sinai continued to meet informally after the sale of its building, but the only formal meeting of its executive board thereafter took place in 1940. At this meeting, the last surviving members of the temple agreed to sell part of the cemetery property for $200.

The Impact of the Jewish Community in St. Francisville

While Jews resided in St. Francisville for only a short time, they maintained a strong presence in civic life. Besides Julius Freyhan and his conglomerate of cotton and dry goods businesses, many Jews owned their own businesses that filled various needs in the community. The Teutsch family ran one of the few grocery stores in town. Morris Burgas owned a very successful dry goods store that offered “competitive prices.” Max Mann, brother of Temple Sinai President Ben Mann, owned one of the most popular bars in the region, right on the Mississippi River where many steamboat passengers stopped for a cold beer or a glass of local whiskey. However, not all Jewish activities in St. Francisville were business ventures. They gave back generously to the community which had given them so much. The Ladies Aid Society, a women’s auxiliary society of Temple Sinai, was organized in 1893 and engaged in humanitarian work throughout Louisiana. In 1908, the Society collected garments from congregants for various charities in West Feliciana Parish and New Orleans under the leadership of Rena Burgas, the wife of Morris Burgas.

The Jewish Community in St. Francisville Today

As the Jewish population of St. Francisville declined into the 20th century, the Ladies Aid Society no longer met and many of the Jewish-run businesses closed. No Jews live in St. Francisville today. Hannah Rosenthal Woods, whose father was Jewish though she was raised Catholic, spent many years caring for the local Jewish cemetery.