Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Monroe, Louisiana

Monroe: Historical Overview

|

In 1969, as the Service Wrecking Company was demolishing the antiquated Jewish temple on the corner of Jackson and Oak Streets in Monroe, workers broke open the building’s original cornerstone. Lodged inside they found a brief history of the congregation known as B’nai Israel, two badly tattered Jewish newsletters, a 1914 edition of the Monroe News-Star, and two pennies. It seems that when the Jewish people of Monroe consecrated the building during World War I, they left a bit of history for future generations.

Monroe’s Jewish community has long recognized the importance of preserving its history. The 1915 documentary history of the congregation found in the cornerstone is only one example of this trend; similar undertakings to write the history of B’nai Israel were performed in 1979 and 1991. The newsletters found in the capsule reveal the far-reaching influence and activities of the Monroe Jewish community, small by big city standards, but relatively large for northeast Louisiana. B’nai Israel provided the Jews of Monroe not only a place for communal worship, but also a center for cultural, social, and charitable organizations. |

The clipping of the Monroe newspaper is significant in that it relates how integral Jew-Gentile relations were in Monroe. In their contributions, Jews did not limit their horizons to the Jewish community. In the words of the Jewish Ledger, “Jew and Gentile labored side by side for the good and welfare of all its people free from cant and prejudice.” Finally, the pennies buried in the cornerstone remind us of how economic prosperity has usually gone hand-in-hand with religious survival. It was through the generosity of the community that hard times were weathered, and through the magnanimity of several wealthy families in Monroe that Jewish life survives in northeast Louisiana to this day. The artifacts found in the cornerstone grant us a window into the unique history of Monroe’s Jewish community.

By virtue of its location on the Ouachita River and its impressive railway infrastructure, Monroe quickly flourished in the post-Civil War era. Remarkably, though the city had only been permanently incorporated in 1855, by the turn of the 20th century Monroe’s population had grown to 18,000.

Today, Monroe is recognized as the birthplace of Delta Airlines and is remembered for the enormous supply of natural gas it provided during World War I. In 1916, Louis Lock discovered the Monroe Gas Field, which provided a key spark for the city’s growth during the war.

Since the mid-19th century, Jews have played an active part in the development of Monroe.

By virtue of its location on the Ouachita River and its impressive railway infrastructure, Monroe quickly flourished in the post-Civil War era. Remarkably, though the city had only been permanently incorporated in 1855, by the turn of the 20th century Monroe’s population had grown to 18,000.

Today, Monroe is recognized as the birthplace of Delta Airlines and is remembered for the enormous supply of natural gas it provided during World War I. In 1916, Louis Lock discovered the Monroe Gas Field, which provided a key spark for the city’s growth during the war.

Since the mid-19th century, Jews have played an active part in the development of Monroe.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Monroe

Early Settlers

Just precisely when the first Jew settled in Monroe is unknown, though early writings mention the presence of Jews in Monroe as early as 1800. Most of the early settlers came from Germany and Poland and were attracted by the Ouachita River’s trading opportunities. Certainly, though, on the eve of the Civil War, the Jewish presence was marked, and the first action taken by the Monroe Jewish community—the purchasing of land for a Jewish cemetery—bespeaks a foresight and determination to establish roots in Monroe. On September 28, 1861, for a grand total of $231.25, Samuel Weil and Henry Gerson, representing “Hebrew Congregation Manassas,” bought land to be used as the “Hebrew Burying Ground” from the Vicksburg, Shreveport and Texas Railroad. The cemetery was ironically named “Beth Ha-Chaim” (House of Life). The cemetery, to this day, houses the spirit of Monroe’s Jewish past. The fledgling congregation still lacked a house of prayer, and so, from 1861 until 1870, worshipers gathered in various homes, including that of Gottliebe King, a wealthy German-born merchant, while Lazarus Meyer led services.

Just precisely when the first Jew settled in Monroe is unknown, though early writings mention the presence of Jews in Monroe as early as 1800. Most of the early settlers came from Germany and Poland and were attracted by the Ouachita River’s trading opportunities. Certainly, though, on the eve of the Civil War, the Jewish presence was marked, and the first action taken by the Monroe Jewish community—the purchasing of land for a Jewish cemetery—bespeaks a foresight and determination to establish roots in Monroe. On September 28, 1861, for a grand total of $231.25, Samuel Weil and Henry Gerson, representing “Hebrew Congregation Manassas,” bought land to be used as the “Hebrew Burying Ground” from the Vicksburg, Shreveport and Texas Railroad. The cemetery was ironically named “Beth Ha-Chaim” (House of Life). The cemetery, to this day, houses the spirit of Monroe’s Jewish past. The fledgling congregation still lacked a house of prayer, and so, from 1861 until 1870, worshipers gathered in various homes, including that of Gottliebe King, a wealthy German-born merchant, while Lazarus Meyer led services.

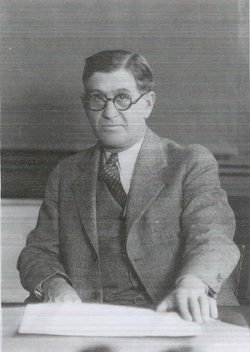

Arnold Bernstein

Arnold Bernstein

Organized Jewish Life in Monroe

On September 4, 1868, Jewish life in Monroe was solidified, as the congregation was incorporated as “B’nai Israel.” According to their charter, the purpose of B’nai Israel was to “erect a synagogue for the worship of God. To institute schools and seminaries of learning for education of children and youth. To dispense charities and to establish customs for the burial of the dead.” The group’s charter members were Henry Gerson, Joseph Hoffman, Sigmund Meyer, Isaac Shuster, Mose Febleman, Simon Marx, and Henry Gross. The following year, they acquired land and built a synagogue on Jackson Street. Despite the new brick building, the congregation could not support a rabbi nor conduct Sabbath school properly, instead convening for worship mostly on the High Holidays; for the rest of the year, most of the temple’s 200 seats remained empty. Nevertheless, the community continued to grow, and by 1878, 128 Jews lived in Monroe.

Eventually, B’nai Israel was able to hire a rabbi. The congregation’s first settled rabbi was Rabbi Gluck, who delivered most of his lectures in German. By 1873, Gluck was succeeded by Rabbi A. Levy, a well-respected rabbi both within the community and among the greater population of Monroe. Upon his departure from B’nai Israel for St. Louis, the Monroe Bulletin observed, “We regret the change. We have found Dr. Levy a learned and excellent gentleman.” In 1874, B’nai Israel conducted its first confirmation services, showing its early adherence to Reform Judaism. Since its founding, B’nai Israel has employed 21 rabbis, including most notably Rabbi Israel Heinberg (1889-1913) and Rabbi F.K. Hirsch (1928-1955).

During the late 19th century, the Monroe Jewish community continued to develop. B’nai Israel held regular Shabbat services and had a weekly religious school. The Temple’s Ladies’ Aid Society provided charity. During the 1920s, the society became known as the Temple Sisterhood, which remains active today. The affiliated B’nai Brith chapter, Adassa Lodge no. 208, founded in 1882, provided congregants an opportunity to gather socially. In 1904, Monroe Jews founded the Unity Club, changing its name to the Young Men’s Hebrew Association in 1913. They acquired a clubhouse at 115 Catalpa Street, which was used for literary, cultural, and social functions. The importance of these local institutions in maintaining a Jewish community is reflected in the newsletter buried in the 1914 cornerstone.

On September 4, 1868, Jewish life in Monroe was solidified, as the congregation was incorporated as “B’nai Israel.” According to their charter, the purpose of B’nai Israel was to “erect a synagogue for the worship of God. To institute schools and seminaries of learning for education of children and youth. To dispense charities and to establish customs for the burial of the dead.” The group’s charter members were Henry Gerson, Joseph Hoffman, Sigmund Meyer, Isaac Shuster, Mose Febleman, Simon Marx, and Henry Gross. The following year, they acquired land and built a synagogue on Jackson Street. Despite the new brick building, the congregation could not support a rabbi nor conduct Sabbath school properly, instead convening for worship mostly on the High Holidays; for the rest of the year, most of the temple’s 200 seats remained empty. Nevertheless, the community continued to grow, and by 1878, 128 Jews lived in Monroe.

Eventually, B’nai Israel was able to hire a rabbi. The congregation’s first settled rabbi was Rabbi Gluck, who delivered most of his lectures in German. By 1873, Gluck was succeeded by Rabbi A. Levy, a well-respected rabbi both within the community and among the greater population of Monroe. Upon his departure from B’nai Israel for St. Louis, the Monroe Bulletin observed, “We regret the change. We have found Dr. Levy a learned and excellent gentleman.” In 1874, B’nai Israel conducted its first confirmation services, showing its early adherence to Reform Judaism. Since its founding, B’nai Israel has employed 21 rabbis, including most notably Rabbi Israel Heinberg (1889-1913) and Rabbi F.K. Hirsch (1928-1955).

During the late 19th century, the Monroe Jewish community continued to develop. B’nai Israel held regular Shabbat services and had a weekly religious school. The Temple’s Ladies’ Aid Society provided charity. During the 1920s, the society became known as the Temple Sisterhood, which remains active today. The affiliated B’nai Brith chapter, Adassa Lodge no. 208, founded in 1882, provided congregants an opportunity to gather socially. In 1904, Monroe Jews founded the Unity Club, changing its name to the Young Men’s Hebrew Association in 1913. They acquired a clubhouse at 115 Catalpa Street, which was used for literary, cultural, and social functions. The importance of these local institutions in maintaining a Jewish community is reflected in the newsletter buried in the 1914 cornerstone.

Civic Engagement

If the newsletter represents the important work done within Monroe’s Jewish community, then the major newspaper found in the cornerstone symbolizes more than just the date the original brick was laid. Instead, it should be seen as the community’s effort to integrate into the greater Monroe society. This effort began, it seems, immediately upon arrival. Like other Southern Jews, Louisiana’s Jewish community patriotically answered the Confederate call to arms. At least 14 Jewish men from the Monroe area fought for the Confederacy, including Henry Gerson, Jacob Kaliski, and Sigmund Meyer and the Silbernagle brothers. During World War I, several Jewish congregants from Monroe contributed to “D” Company of the 156th Infantry Regiment, including men named Sugar, Stern, Goldman and Brooks. Years later, of the 150 member families of B’nai Israel in the early 1940s, nearly half had someone serve in the military during World War II.

Monroe Jews also played a significant role in local politics. After the Civil War, Jacob Kaliski served as a representative to the state legislature. The Kaliski family was especially concerned with promoting and improving education in Monroe. Jacob was responsible for securing the Louisiana Training Institute in south Monroe. Arnold Bernstein served as mayor of Monroe for almost 20 years, from 1918 to 1937. In 1919, Bernstein ushered in an era of unprecedented growth for the relatively small town: the city utilities system doubled, a modern sewage system was put in place, concrete streets and sidewalks were constructed throughout the city, and the number of schools increased six-fold. Even during the heyday of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s, Bernstein never faced serious political opposition. David C. Silverstein served on a government committee that led to the construction of the Monroe Civic Center.

Jewish contributions to life in Monroe went beyond politics as well. The Strauss Theater Center, completed in 1961, is named for Fred “Pap” Strauss whose son and daughter-in-law, Clifford and Roselyn Strauss, were the benefactors. The same family also helped found the Carolyn Rose Strauss Rehabilitation Center. In the arena of sports, the Jews of Monroe were also highly active, as Albert Marx and Sam Smith, both members of B’nai Israel, played for the Monroe Athletics, the semi-pro franchise team of the Philadelphia Athletics. After World War II, under Saul Adler’s leadership, Monroe acquired a farm team from the New York Yankees.

Jews have long enjoyed strong relations with their non-Jewish neighbors in Monroe. During the years of the Great Depression, Monroe’s citizens were tested, Jew and Gentile alike, as economic activity came to a startling halt. In the wake of failed government intervention, local religious bodies took up the burden. B’nai Israel established itself as one of the premier relief organizations. One instance of such charity involved M. Kaplan and Son setting up a meal ticket system, by which the city’s poor could be fed at local restaurants. More acts of benevolence were necessary especially as new German immigrants arrived in Monroe fleeing Nazi Germany. The Sisterhood’s War Service Committee was instrumental in providing food and entertainment for servicemen. A 2003 article in the News-Star summed up the contribution of Jews in Monroe nicely: “From sports to education to the arts, Jewish residents helped build many of Monroe’s key institutions.”

If the newsletter represents the important work done within Monroe’s Jewish community, then the major newspaper found in the cornerstone symbolizes more than just the date the original brick was laid. Instead, it should be seen as the community’s effort to integrate into the greater Monroe society. This effort began, it seems, immediately upon arrival. Like other Southern Jews, Louisiana’s Jewish community patriotically answered the Confederate call to arms. At least 14 Jewish men from the Monroe area fought for the Confederacy, including Henry Gerson, Jacob Kaliski, and Sigmund Meyer and the Silbernagle brothers. During World War I, several Jewish congregants from Monroe contributed to “D” Company of the 156th Infantry Regiment, including men named Sugar, Stern, Goldman and Brooks. Years later, of the 150 member families of B’nai Israel in the early 1940s, nearly half had someone serve in the military during World War II.

Monroe Jews also played a significant role in local politics. After the Civil War, Jacob Kaliski served as a representative to the state legislature. The Kaliski family was especially concerned with promoting and improving education in Monroe. Jacob was responsible for securing the Louisiana Training Institute in south Monroe. Arnold Bernstein served as mayor of Monroe for almost 20 years, from 1918 to 1937. In 1919, Bernstein ushered in an era of unprecedented growth for the relatively small town: the city utilities system doubled, a modern sewage system was put in place, concrete streets and sidewalks were constructed throughout the city, and the number of schools increased six-fold. Even during the heyday of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s, Bernstein never faced serious political opposition. David C. Silverstein served on a government committee that led to the construction of the Monroe Civic Center.

Jewish contributions to life in Monroe went beyond politics as well. The Strauss Theater Center, completed in 1961, is named for Fred “Pap” Strauss whose son and daughter-in-law, Clifford and Roselyn Strauss, were the benefactors. The same family also helped found the Carolyn Rose Strauss Rehabilitation Center. In the arena of sports, the Jews of Monroe were also highly active, as Albert Marx and Sam Smith, both members of B’nai Israel, played for the Monroe Athletics, the semi-pro franchise team of the Philadelphia Athletics. After World War II, under Saul Adler’s leadership, Monroe acquired a farm team from the New York Yankees.

Jews have long enjoyed strong relations with their non-Jewish neighbors in Monroe. During the years of the Great Depression, Monroe’s citizens were tested, Jew and Gentile alike, as economic activity came to a startling halt. In the wake of failed government intervention, local religious bodies took up the burden. B’nai Israel established itself as one of the premier relief organizations. One instance of such charity involved M. Kaplan and Son setting up a meal ticket system, by which the city’s poor could be fed at local restaurants. More acts of benevolence were necessary especially as new German immigrants arrived in Monroe fleeing Nazi Germany. The Sisterhood’s War Service Committee was instrumental in providing food and entertainment for servicemen. A 2003 article in the News-Star summed up the contribution of Jews in Monroe nicely: “From sports to education to the arts, Jewish residents helped build many of Monroe’s key institutions.”

The Community Grows

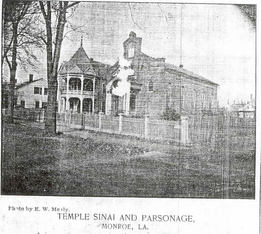

The relative lack of anti-Semitism in Monroe continued even as large numbers of Eastern European Jews began to settle in town in the early 20th century. In 1905, about 200 Jews lived in town; by 1927, 500 did. Surprisingly, no serious tension developed between the Russian Jews and the already-settled German Jews of Monroe. The newcomers chose to join the Reform congregation B’nai Israel rather than start their own synagogue. By 1913, the congregation had grown to 90 members. In 1916, B’nai Israel acquired land for a new temple; the new structure, completed the following year, was a Romanesque, brick and terracotta structure that could seat 400. To pay for the expensive new structure, temple president Barney Sugar started a nationwide fundraising campaign, asking every congregation in the country to contribute $1 to the cause. In 1921, congregants erected a parsonage and garage for the congregation’s rabbi. Rabbi Harry Merfeld was the first to occupy the new abode. During the immediate pre-Depression years, most members paid $2 per month in temple fees, while several wealthy members—including the Masurs, the Sugars, the Kaplan, and the Blocks—opted to pay $20 or $25 a month.

The relative lack of anti-Semitism in Monroe continued even as large numbers of Eastern European Jews began to settle in town in the early 20th century. In 1905, about 200 Jews lived in town; by 1927, 500 did. Surprisingly, no serious tension developed between the Russian Jews and the already-settled German Jews of Monroe. The newcomers chose to join the Reform congregation B’nai Israel rather than start their own synagogue. By 1913, the congregation had grown to 90 members. In 1916, B’nai Israel acquired land for a new temple; the new structure, completed the following year, was a Romanesque, brick and terracotta structure that could seat 400. To pay for the expensive new structure, temple president Barney Sugar started a nationwide fundraising campaign, asking every congregation in the country to contribute $1 to the cause. In 1921, congregants erected a parsonage and garage for the congregation’s rabbi. Rabbi Harry Merfeld was the first to occupy the new abode. During the immediate pre-Depression years, most members paid $2 per month in temple fees, while several wealthy members—including the Masurs, the Sugars, the Kaplan, and the Blocks—opted to pay $20 or $25 a month.

Jewish Businesses in Monroe

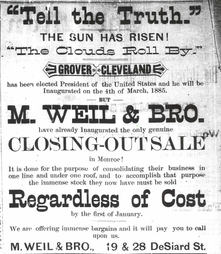

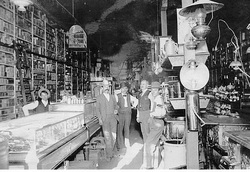

The Jewish community was dominated by several major families, who made their fortunes in the retail business and brokered close relations with the larger Southern population. The Kaliski, Baer, Weil, Meyer, Sugar, Gerson, Marx, and Masur families were at the heart of Monroe’s early Jewish life. These prominent families were all headed by German-born immigrants who made their fortunes as merchants and retail store owners. The Meyer family, for instance, owned the largest ladies ready-to-wear store in northeast Louisiana. Sigmund and Herman Masur were born in Germany in the 1880s. After arriving in the United States in 1889, they and their father, David, opened D. Masur and Sons, then later Sigmund and Herman opened a department store known as The Palace. In this endeavor, the Masur brothers were tremendously successful. The town’s Masur Museum of Art, which opened in 1964, is named for Sigmund and Beatrice Masur, and is housed in their former residence.

For most of the 20th century, business was good for the Jews of Monroe. By the 1940s, Jewish-owned stores dotted Monroe, from R&A Jewelers to The Woman Shop, to Bodan’s Rexall Drugs, to Krauss and Cahn, to Field’s Ladies, to Fink's Men's Wear, to Silverstein’s Ladies’ to Aron’s Pharmacy. Sam, Barney, and Isadore Sugar were brothers who built a thriving grocery business. After achieving success, they built Monroe’s first theatre. The Marx family founded the Southern Hardware Company in 1889. Joe Marx III, who has served on the Monroe City Council, continues to run the business today at the same location since 1920. Clifford Strauss and his father, Fred “Pap” Strauss, were local philanthropists who made their fortunes in the wholesale food and wine and spirit business. Clifford and Roselyn’s daughter, Jean Strauss Mintz, and her husband Saul, remain major contributors and active supporters of various Jewish, civic, and social justice causes.

The Jewish community was dominated by several major families, who made their fortunes in the retail business and brokered close relations with the larger Southern population. The Kaliski, Baer, Weil, Meyer, Sugar, Gerson, Marx, and Masur families were at the heart of Monroe’s early Jewish life. These prominent families were all headed by German-born immigrants who made their fortunes as merchants and retail store owners. The Meyer family, for instance, owned the largest ladies ready-to-wear store in northeast Louisiana. Sigmund and Herman Masur were born in Germany in the 1880s. After arriving in the United States in 1889, they and their father, David, opened D. Masur and Sons, then later Sigmund and Herman opened a department store known as The Palace. In this endeavor, the Masur brothers were tremendously successful. The town’s Masur Museum of Art, which opened in 1964, is named for Sigmund and Beatrice Masur, and is housed in their former residence.

For most of the 20th century, business was good for the Jews of Monroe. By the 1940s, Jewish-owned stores dotted Monroe, from R&A Jewelers to The Woman Shop, to Bodan’s Rexall Drugs, to Krauss and Cahn, to Field’s Ladies, to Fink's Men's Wear, to Silverstein’s Ladies’ to Aron’s Pharmacy. Sam, Barney, and Isadore Sugar were brothers who built a thriving grocery business. After achieving success, they built Monroe’s first theatre. The Marx family founded the Southern Hardware Company in 1889. Joe Marx III, who has served on the Monroe City Council, continues to run the business today at the same location since 1920. Clifford Strauss and his father, Fred “Pap” Strauss, were local philanthropists who made their fortunes in the wholesale food and wine and spirit business. Clifford and Roselyn’s daughter, Jean Strauss Mintz, and her husband Saul, remain major contributors and active supporters of various Jewish, civic, and social justice causes.

The Jewish Community in Monroe Today

Monroe’s Jewish population reached a plateau of an estimated 500 people between the 1920’s and 1980s. Over the last few decades, Monroe’s Jewish community has declined sharply. Today, only about 130 Jews live in the Monroe area. B’nai Israel, which moved to a new building on Orell Place in 1961, continues to serve as a hub of Jewish life in the area, attracting members from nearby towns like Bastrop, Ruston, Farmerville, and Winnsboro. The congregation, whose last full-time rabbi retired in 2003, is now served on a part-time basis by a visiting rabbi. Friday night worship services are conducted by its lay members when a rabbi isn’t there. As it has throughout its history, Monroe continues as a bastion of Jewish life in northeast Louisiana. In its efforts to preserve the tremendous contributions the members of the Jewish community have made to Monroe, the Temple has created a very active archive program known as its “Precious Legacy.”