Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Owensboro, Kentucky

Owensboro: Historical Overview

Located on the Ohio River, Owensboro, Kentucky, was incorporated in 1817. The town grew slowly, with only 229 residents in 1830, but by the middle of the 19th century, Owensboro was developing into a commercial center. By 1860, about 2500 people lived in the town. Owensboro enjoyed an industrial boom with the arrival of the railroad, growing to 6,200 people by 1880, and over 17,000 by 1920. Owensboro’s emergence as a trading hub for western Kentucky led to the rise of a small but enduring Jewish community.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Owensboro

Early Settlers

Jews first settled in Owensboro in the 1840s. Among the first was Marcus Suntheimer, a German immigrant who opened a store in Owensboro. A growing number of Jewish immigrants from Alsace and the German states came to Owensboro in the 1850s. These included Max Kohn, Phillip Rothschild, Henry Mendel, Ernest Weil, Abraham Hirsch, Samuel Moise, and Simon Greenbaum. Nearly all of these early Jewish residents opened retail stores catering to the town’s growing population. Several became successful. By 1860, Suntheimer owned approximately $8,000 worth of personal property and real estate. Solomon Wile, who came to the United States from Baden in 1855, moved to Owensboro just after the start of the Civil War. The business he opened on Main Street quickly grew and Wile was able to build a large new building to house the store in 1865. After the war, Wile’s business kept expanding, and he became one of Owensboro’s most respected and successful merchants.

Prussian-born Bernard Baer also came to Owensboro in 1861. Baer was involved with various different businesses over the years, but was especially active in local politics. Baer served several years on the city council and was mayor pro tem. He even ran for mayor in 1882, though he didn’t win. Joseph Rothchild, who left France in 1858, moved to Owensboro in 1865 after spending several years in Louisville. In 1873, he opened a wholesale and retail dry goods business that eventually became the largest store in town. Like Baer, Rothchild was also a civic leader, serving on the Owensboro school board before his death in 1888. Alsatian-born Moses Levy opened a dry goods store in 1872. Later, his children worked in the store, which remained in business for almost a century. Levy had fought for the Confederacy during the war, even though he didn’t arrive in the country until 1857. In 1890, he joined the recently formed Daviess County Confederate Association. His daughter, Rose Levy Siegel, became a founding member of the local chapter of the Daughters of the Confederacy. Levy’s Confederate credentials did not hurt him in western Kentucky. Although it remained in the Union, Kentucky had considerable Confederate sympathies.

Jews first settled in Owensboro in the 1840s. Among the first was Marcus Suntheimer, a German immigrant who opened a store in Owensboro. A growing number of Jewish immigrants from Alsace and the German states came to Owensboro in the 1850s. These included Max Kohn, Phillip Rothschild, Henry Mendel, Ernest Weil, Abraham Hirsch, Samuel Moise, and Simon Greenbaum. Nearly all of these early Jewish residents opened retail stores catering to the town’s growing population. Several became successful. By 1860, Suntheimer owned approximately $8,000 worth of personal property and real estate. Solomon Wile, who came to the United States from Baden in 1855, moved to Owensboro just after the start of the Civil War. The business he opened on Main Street quickly grew and Wile was able to build a large new building to house the store in 1865. After the war, Wile’s business kept expanding, and he became one of Owensboro’s most respected and successful merchants.

Prussian-born Bernard Baer also came to Owensboro in 1861. Baer was involved with various different businesses over the years, but was especially active in local politics. Baer served several years on the city council and was mayor pro tem. He even ran for mayor in 1882, though he didn’t win. Joseph Rothchild, who left France in 1858, moved to Owensboro in 1865 after spending several years in Louisville. In 1873, he opened a wholesale and retail dry goods business that eventually became the largest store in town. Like Baer, Rothchild was also a civic leader, serving on the Owensboro school board before his death in 1888. Alsatian-born Moses Levy opened a dry goods store in 1872. Later, his children worked in the store, which remained in business for almost a century. Levy had fought for the Confederacy during the war, even though he didn’t arrive in the country until 1857. In 1890, he joined the recently formed Daviess County Confederate Association. His daughter, Rose Levy Siegel, became a founding member of the local chapter of the Daughters of the Confederacy. Levy’s Confederate credentials did not hurt him in western Kentucky. Although it remained in the Union, Kentucky had considerable Confederate sympathies.

Bernard Baer

Bernard Baer

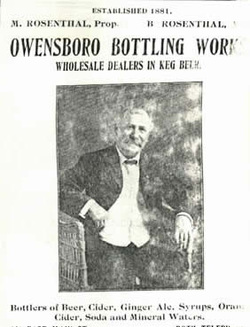

In 1877, the local newspaper noted the proliferation of Jewish-owned stores in Owensboro, writing “from one end of Main Street to the other their business banners will be found upon the outer walls.” The newspaper praised the city’s Jewish merchants, claiming that “the city owes much of its commercial reputation to the vim and enterprise of this class of people.” According to the 1882 city directory, Jews dominated the retail clothing business in Owensboro. Of the thirteen clothing stores in the city, eight were Jewish-owned. Jews also owned an array of other businesses. Bernhardt Rosenthal opened a bottling works in Owensboro in 1881 while the Rosenfeld family owned a whiskey distillery. Phillip Dahl lived in Owensboro by 1882, and soon opened a hide, fur, and root business with his partner George Groezinger. Groezinger, who was not Jewish, had met Dahl while they were both emigrating on the same boat from Germany. In the early 20th century, Dahl & Groezinger expanded into scrap metal. Dahl left the successful scrap business in 1927, while the Groezinger family continues to run it today.

Organized Jewish Life in Owensboro

Organized Jewish life began in Owensboro in the late 1850s, with the creation of a Hebrew Benefit and Burial Society. In 1862, the society bought land for a cemetery for $75. In 1865, the group established a formal congregation, Adath Israel, holding their first services on the second floor of Sam Moise’s store. The fledgling congregation later met at a local school building. From its beginning, the congregation was Reform, joining the Union of American Hebrew Congregations in 1873. In 1874, the group bought land on Daviess Street to build a synagogue. When the $4000 building was completed in 1877, the congregation held a large public dedication featuring a rabbi from Evansville, Indiana. The synagogue, which could seat 200 in its pews, had a Moorish revival façade, along with Gothic style windows and doors. The members of Adath Israel, who numbered only thirteen families in 1875, expected the congregation to grow and eventually fill the sanctuary, though it never really did.

Organized Jewish Life in Owensboro

Organized Jewish life began in Owensboro in the late 1850s, with the creation of a Hebrew Benefit and Burial Society. In 1862, the society bought land for a cemetery for $75. In 1865, the group established a formal congregation, Adath Israel, holding their first services on the second floor of Sam Moise’s store. The fledgling congregation later met at a local school building. From its beginning, the congregation was Reform, joining the Union of American Hebrew Congregations in 1873. In 1874, the group bought land on Daviess Street to build a synagogue. When the $4000 building was completed in 1877, the congregation held a large public dedication featuring a rabbi from Evansville, Indiana. The synagogue, which could seat 200 in its pews, had a Moorish revival façade, along with Gothic style windows and doors. The members of Adath Israel, who numbered only thirteen families in 1875, expected the congregation to grow and eventually fill the sanctuary, though it never really did.

Ad for Bernhardt Rosenthal's bottling works

Ad for Bernhardt Rosenthal's bottling works

Despite its small size, Adath Israel was able to employ a series of full-time rabbis during its early years. Between 1865 and 1881, seven different rabbis led the congregation. In 1881, Adath Israel hired Rabbi Joseph Glueck, who would be Adath Israel’s longest serving spiritual leader. During his 13-year tenure, the congregation flourished, growing to 31 families with 46 children in its religious school by the mid-1880s. When Glueck left in 1894, he was replaced by David Feuerlicht, who only served for two years before dying in 1896. After Feuerlicht’s death, the congregation would bring in student rabbis from Hebrew Union College to lead High Holiday services while relying on lay leaders the rest of the year. Most of these early rabbis were not formally ordained and did not belong to the Central Conference of American Rabbis.

While the congregation was undoubtedly Reform, with a female choir singing during services, they still followed some traditional practices. During Rabbi Glueck’s tenure, boys were bar mitzvahed at Adath Israel. By 1900, the congregation had 18 members and 33 children in its religious school. Even though they did not have a rabbi at the time, the congregation still held weekly Shabbat services on Friday nights and Saturday mornings.

In 1903, Adath Israel hired Rabbi Nathan Krasnowetz, the first and only Hebrew Union College graduate to hold the pulpit full-time. Krasnowetz came to Owensboro right after graduating from HUC to serve the small congregation, which had about 100 souls at the time. The rabbi, who shortened his last name to Krass during his tenure in Owensboro, gave a special sermon in 1905 about the discrimination and violence Jews faced in Russia. That night, Krass raised $300 for the Jewish Relief Fund from his congregation, and after the speech was covered in great detail by the local newspaper, many non-Jews in Owensboro also donated to the fund. Rabbi Krass left in 1907 for a pulpit in Lafayette, Indiana. Arthur Zinkin replaced Krass at Adath Israel, though he too left in 1910. The congregation then turned to Theodore Levy, the son of Moses and Allie Levy, who had grown up in Owensboro and had “studied in a Jewish college in the North,” according to the Owensboro Messenger. It’s unclear if Levy was an ordained rabbi, though he also worked in his family’s clothing store during his time leading Adath Israel. Levy was very involved in the larger community, organizing Owensboro’s Associated Charities organization in 1915. He served as the group’s first president and was also head of the Owensboro Rotary Club. Levy died tragically in 1919 at the age of 31. In 1930, his family donated his house to become a children’s home. The Levy Memorial Home remained in operation until 1985.

While the congregation was undoubtedly Reform, with a female choir singing during services, they still followed some traditional practices. During Rabbi Glueck’s tenure, boys were bar mitzvahed at Adath Israel. By 1900, the congregation had 18 members and 33 children in its religious school. Even though they did not have a rabbi at the time, the congregation still held weekly Shabbat services on Friday nights and Saturday mornings.

In 1903, Adath Israel hired Rabbi Nathan Krasnowetz, the first and only Hebrew Union College graduate to hold the pulpit full-time. Krasnowetz came to Owensboro right after graduating from HUC to serve the small congregation, which had about 100 souls at the time. The rabbi, who shortened his last name to Krass during his tenure in Owensboro, gave a special sermon in 1905 about the discrimination and violence Jews faced in Russia. That night, Krass raised $300 for the Jewish Relief Fund from his congregation, and after the speech was covered in great detail by the local newspaper, many non-Jews in Owensboro also donated to the fund. Rabbi Krass left in 1907 for a pulpit in Lafayette, Indiana. Arthur Zinkin replaced Krass at Adath Israel, though he too left in 1910. The congregation then turned to Theodore Levy, the son of Moses and Allie Levy, who had grown up in Owensboro and had “studied in a Jewish college in the North,” according to the Owensboro Messenger. It’s unclear if Levy was an ordained rabbi, though he also worked in his family’s clothing store during his time leading Adath Israel. Levy was very involved in the larger community, organizing Owensboro’s Associated Charities organization in 1915. He served as the group’s first president and was also head of the Owensboro Rotary Club. Levy died tragically in 1919 at the age of 31. In 1930, his family donated his house to become a children’s home. The Levy Memorial Home remained in operation until 1985.

Adath Israel's 1877 synagogue

Adath Israel's 1877 synagogue

Adath Israel was not the only Jewish organization in Owensboro. A B’nai B’rith lodge was founded in 1874. Adath Israel had a Ladies Aid Society, which later became the Sisterhood. In 1907, there was also the Adeline Rosenfeld Sewing Society, which made clothes for the needy. In 1889, Owensboro Jews established the Standard Club, which according to the local newspaper was “chartered for the purpose of literary and social enjoyment.” The group, led by its first president Emanuel Bamberger, rented space and outfitted a library and a gymnasium. In 1890, the club held an elegant ball that drew young Jews from Evansville, Indiana, Louisville, Chicago, and several small towns in Kentucky. The Owensboro Messenger ran a long story about the event, including a listing of all of the attendees along with a detailed description of each woman’s dress and accessories. As the paper noted, “there are no people who enjoy a festive occasion or dispense a more lavish hospitality than the Hebrews.”

By 1900, the Standard Club had 20 members, mostly young men. Although it was a purely social organization, the Standard Club was closely tied to Adath Israel. In 1900, its president, Phillip Dahl, was also treasurer of the congregation. By 1901, the Standard Club was meeting at the Temple Theater. The group remained active as late as 1919, but eventually disbanded in the 1920s when the Owensboro Jewish community declined significantly.

By 1900, the Standard Club had 20 members, mostly young men. Although it was a purely social organization, the Standard Club was closely tied to Adath Israel. In 1900, its president, Phillip Dahl, was also treasurer of the congregation. By 1901, the Standard Club was meeting at the Temple Theater. The group remained active as late as 1919, but eventually disbanded in the 1920s when the Owensboro Jewish community declined significantly.

The Community Declines

According to estimates in the American Jewish Year Book, Owensboro’s Jewish population dropped from 230 people in 1919 to only 49 in 1927. While the actual decline was probably not as steep as these estimates suggest, since Adath Israel had 23 families in 1925, the Owensboro Jewish community had clearly begun to shrink by the 1920s. After the early 1920s, Adath Israel was no longer able to afford a full-time rabbi, and relied on student rabbis from HUC for the next seven decades. While most Owensboro Jews remained merchants, their numbers declined during the early 20th century. In 1901, there were at least 14 Jewish owned businesses in town, although they no longer dominated the clothing and dry goods industries as they had in the 1880s. By 1918, there were fewer Jewish-owned businesses in town as the Eastern European wave of Jewish immigration did not have a significant impact on Owensboro.

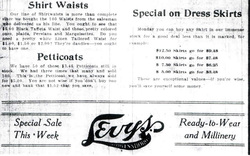

Despite this overall decline, several Jewish-owned businesses flourished in Owensboro in the early 20th century, in many cases led by the children of their founders. Solomon Wile’s sons Joe, Henry, and Ben took over their father’s store after he died in 1886, renaming it Wile Brothers. Ben Wile left the business in 1913 and helped to establish the Farmers’ and Traders’ Bank, later serving as its president. Henry’s son Mark Wile later ran the store. Sam Levy took over his father Moses’ store. When Sam died in 1951, his son Lawrence ran Levy’s, which sold high-end clothing. Lawrence and his mother Anna operated the store until they closed it in 1971. Alex Feuerlicht owned the Fair Store in 1901. By 1918, his sisters Hattie and Jennie Feuerlicht, both of whom were single, owned the millinery store. The sisters ran the business until it closed in the early 1940s. Robert Kaplan moved to Owensboro from Louisville in the 1930s and opened the Interstate Department Store. Kaplan hired other Jews, including Harry and Lena Goldstein, to work in the store. Kaplan ran the business until he closed it in 1986. Interstate was the last Jewish-owned clothing store in Owensboro.

According to estimates in the American Jewish Year Book, Owensboro’s Jewish population dropped from 230 people in 1919 to only 49 in 1927. While the actual decline was probably not as steep as these estimates suggest, since Adath Israel had 23 families in 1925, the Owensboro Jewish community had clearly begun to shrink by the 1920s. After the early 1920s, Adath Israel was no longer able to afford a full-time rabbi, and relied on student rabbis from HUC for the next seven decades. While most Owensboro Jews remained merchants, their numbers declined during the early 20th century. In 1901, there were at least 14 Jewish owned businesses in town, although they no longer dominated the clothing and dry goods industries as they had in the 1880s. By 1918, there were fewer Jewish-owned businesses in town as the Eastern European wave of Jewish immigration did not have a significant impact on Owensboro.

Despite this overall decline, several Jewish-owned businesses flourished in Owensboro in the early 20th century, in many cases led by the children of their founders. Solomon Wile’s sons Joe, Henry, and Ben took over their father’s store after he died in 1886, renaming it Wile Brothers. Ben Wile left the business in 1913 and helped to establish the Farmers’ and Traders’ Bank, later serving as its president. Henry’s son Mark Wile later ran the store. Sam Levy took over his father Moses’ store. When Sam died in 1951, his son Lawrence ran Levy’s, which sold high-end clothing. Lawrence and his mother Anna operated the store until they closed it in 1971. Alex Feuerlicht owned the Fair Store in 1901. By 1918, his sisters Hattie and Jennie Feuerlicht, both of whom were single, owned the millinery store. The sisters ran the business until it closed in the early 1940s. Robert Kaplan moved to Owensboro from Louisville in the 1930s and opened the Interstate Department Store. Kaplan hired other Jews, including Harry and Lena Goldstein, to work in the store. Kaplan ran the business until he closed it in 1986. Interstate was the last Jewish-owned clothing store in Owensboro.

1910 ad for Levy's

1910 ad for Levy's

Civic Engagement

Although Owensboro’s Jewish population was small, numbering just 65 people in 1937, they had a significant impact on the larger community. Clemie Wolf was very involved in local charity work. During the 1918 flu epidemic, she was a Red Cross worker who dedicated herself to nursing the sick. When patients died, she used her own linens to prepare and dress their bodies. Wolf’s dedication to nursing ultimately cost her life when she too succumbed to the disease. After her death, Owensboro Jews equipped and named a city hospital room in her honor. Gertrude Weill was also involved in local charity work, serving as the longtime director of the Welfare League of Daviess County. Joseph Weill spent many years on the Owensboro School Board, serving as its president in 1943. Sam Levy headed the local Chamber of Commerce and the Rotary Club.

Although Owensboro’s Jewish population was small, numbering just 65 people in 1937, they had a significant impact on the larger community. Clemie Wolf was very involved in local charity work. During the 1918 flu epidemic, she was a Red Cross worker who dedicated herself to nursing the sick. When patients died, she used her own linens to prepare and dress their bodies. Wolf’s dedication to nursing ultimately cost her life when she too succumbed to the disease. After her death, Owensboro Jews equipped and named a city hospital room in her honor. Gertrude Weill was also involved in local charity work, serving as the longtime director of the Welfare League of Daviess County. Joseph Weill spent many years on the Owensboro School Board, serving as its president in 1943. Sam Levy headed the local Chamber of Commerce and the Rotary Club.

Sukkhot celebration at Adath Israel c. 1950s

Sukkhot celebration at Adath Israel c. 1950s

Mid-Century Growth

In 1942, Adath Israel built a small addition to its synagogue which included meeting rooms that could be used for religious school. After World War II, the congregation grew from 19 families in 1945 to a peak of 45 in 1962. Much of this growth was fueled by the arrival of Jewish professionals. General Electric built a radio vacuum tube plant in Owensboro after the war, which drew Jewish engineers and executives. Nathan Cornfield, a patent lawyer for G.E., moved to Owensboro to work for the company. Other Jewish lawyers in town included Nathan Cooper and Paul Bugay, who moved to Owensboro in 1954. In the 1950s, there was even a Hadassah chapter in Owensboro, which held various fundraisers to support the national organization’s efforts in Israel. There was also an Owensboro Federated Jewish Charities that raised money to support various Jewish causes. In 1973, it raised over $4200, twice as much as the previous year, due to the response to Israel’s Yom Kippur War. Over 90% of the money was donated to the United Jewish Appeal, with the remainder being given to various Jewish charities in Israel and the U.S.

In 1942, Adath Israel built a small addition to its synagogue which included meeting rooms that could be used for religious school. After World War II, the congregation grew from 19 families in 1945 to a peak of 45 in 1962. Much of this growth was fueled by the arrival of Jewish professionals. General Electric built a radio vacuum tube plant in Owensboro after the war, which drew Jewish engineers and executives. Nathan Cornfield, a patent lawyer for G.E., moved to Owensboro to work for the company. Other Jewish lawyers in town included Nathan Cooper and Paul Bugay, who moved to Owensboro in 1954. In the 1950s, there was even a Hadassah chapter in Owensboro, which held various fundraisers to support the national organization’s efforts in Israel. There was also an Owensboro Federated Jewish Charities that raised money to support various Jewish causes. In 1973, it raised over $4200, twice as much as the previous year, due to the response to Israel’s Yom Kippur War. Over 90% of the money was donated to the United Jewish Appeal, with the remainder being given to various Jewish charities in Israel and the U.S.

The Jewish Community in Owensboro Today

Stuart Spindel and Sandy Bugay

Stuart Spindel and Sandy Bugay inside Adath Israel's sanctuary

By 1972, Adath Israel had shrunk back to 19 families; 13 lived in Owensboro, while the rest lived in surrounding towns. Despite these small numbers, the congregation persevered. In 1983, they still had about a dozen children in their religious school. HUC student rabbis came to Owensboro every other week to lead Shabbat services. But as these children grew up, they moved away to larger cities as the Owensboro Jewish community grew elderly. By 1996, Adath Israel was only receiving monthly visits from their student rabbi and the religious school had closed. After 1999, the congregation was too small to support a student rabbi and Dr. Robert Taxman then served as lay leader for services.

In 2012, Adath Israel had about 12 individual members. Sandy Bugay and Stuart Spindel lead the High Holiday and monthly Shabbat services. While they only meet on the first Friday night of each month for services, the congregation holds a weekly Friday night Torah study at the temple. Gentiles often outnumber the Jews at services and Torah study. The congregation regularly holds interfaith events which bring non-Jews into the synagogue to learn about Judaism.

Adath Israel continues to meet in its original 1877 temple, making it one of the oldest synagogues still in use in America. The congregation remains in its beautiful synagogue, which is on the National Register of Historic Places, because they never outgrew it. This will likely never happen as the decline in Adath Israel’s membership over the last few decades has put the future of the congregation in doubt. Nevertheless, the remaining members are committed to maintaining Jewish life in Owensboro for as long as they can.

In 2012, Adath Israel had about 12 individual members. Sandy Bugay and Stuart Spindel lead the High Holiday and monthly Shabbat services. While they only meet on the first Friday night of each month for services, the congregation holds a weekly Friday night Torah study at the temple. Gentiles often outnumber the Jews at services and Torah study. The congregation regularly holds interfaith events which bring non-Jews into the synagogue to learn about Judaism.

Adath Israel continues to meet in its original 1877 temple, making it one of the oldest synagogues still in use in America. The congregation remains in its beautiful synagogue, which is on the National Register of Historic Places, because they never outgrew it. This will likely never happen as the decline in Adath Israel’s membership over the last few decades has put the future of the congregation in doubt. Nevertheless, the remaining members are committed to maintaining Jewish life in Owensboro for as long as they can.