Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Henderson, Kentucky

Henderson: Historical Overview

Located on the Ohio River just across from Indiana, Henderson, Kentucky, became a town in 1797. By the 1850s, Henderson had become a center of the tobacco growing industry, with several warehouses and stemmeries located in the growing town. By 1870, over 4,000 people lived in the seat of Henderson County.

Jews first came to Henderson during the mid-19th century, drawn by the booming local tobacco economy. They formed a community that was small but active, lasting into the 20th century.

Jews first came to Henderson during the mid-19th century, drawn by the booming local tobacco economy. They formed a community that was small but active, lasting into the 20th century.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Henderson

1892 ad for S.&E. Oberdorfer

1892 ad for S.&E. Oberdorfer

Early Jewish Residents

Herman Schlesinger, a Prussian-born merchant, lived in Henderson by the time of the Civil War. A few other Jewish merchants lived in Henderson during the war, including Bernard Baum and N. Heyman. Wartime was often difficult for these merchants as Rebel soldiers would come into Henderson when no Federal troops were there and raid local stores for supplies. In 1864, the raiding got so bad that Schlesinger and Baum closed their businesses and moved their merchandise to Louisville for safe keeping. Only Schlesinger seemed to return to Henderson after the war, rebuilding his business into a prosperous operation. By 1870, Schlesinger owned $12,000 in real estate and $7000 in personal property.

The Community Grows

It was not until after the Civil War that the Henderson Jewish community began to grow and develop as several German Jewish immigrants moved to the town. Simon Oberdorfer came to Kentucky in the 1850s. Once the war broke out, Oberdorfer enlisted with the Union Army in Louisville, serving in the Kentucky infantry. After the war, he moved to Henderson, where he opened the European Hotel, which also had a restaurant and saloon. Oberdorfer was not a traditionally observant Jew, and his restaurant specialized in oysters. Oberdorfer’s sons also settled in Henderson; Lee was a watchmaker who opened a jewelry store, while Nathan was a doctor who owned a pharmacy. Simon’s daughter Pauline married Peter Geibel in 1878; Geibel later opened a store on Main Street. Solomon Oberdorfer, possibly a nephew of Simon, left Bavaria for the U.S. when he was a boy. By 1870 he lived in Henderson. A few years later, he opened a dry goods store with his brother Edward. Their younger brother Nathan later came to work in the store. By 1894, S. & E. Oberdorfer was a flourishing wholesale and retail dry goods operation. By 1900, Edward had left the business to become a whiskey distiller, though this endeavor likely failed since he was working as a traveling salesman in Illinois by 1910.

Herman Schlesinger, a Prussian-born merchant, lived in Henderson by the time of the Civil War. A few other Jewish merchants lived in Henderson during the war, including Bernard Baum and N. Heyman. Wartime was often difficult for these merchants as Rebel soldiers would come into Henderson when no Federal troops were there and raid local stores for supplies. In 1864, the raiding got so bad that Schlesinger and Baum closed their businesses and moved their merchandise to Louisville for safe keeping. Only Schlesinger seemed to return to Henderson after the war, rebuilding his business into a prosperous operation. By 1870, Schlesinger owned $12,000 in real estate and $7000 in personal property.

The Community Grows

It was not until after the Civil War that the Henderson Jewish community began to grow and develop as several German Jewish immigrants moved to the town. Simon Oberdorfer came to Kentucky in the 1850s. Once the war broke out, Oberdorfer enlisted with the Union Army in Louisville, serving in the Kentucky infantry. After the war, he moved to Henderson, where he opened the European Hotel, which also had a restaurant and saloon. Oberdorfer was not a traditionally observant Jew, and his restaurant specialized in oysters. Oberdorfer’s sons also settled in Henderson; Lee was a watchmaker who opened a jewelry store, while Nathan was a doctor who owned a pharmacy. Simon’s daughter Pauline married Peter Geibel in 1878; Geibel later opened a store on Main Street. Solomon Oberdorfer, possibly a nephew of Simon, left Bavaria for the U.S. when he was a boy. By 1870 he lived in Henderson. A few years later, he opened a dry goods store with his brother Edward. Their younger brother Nathan later came to work in the store. By 1894, S. & E. Oberdorfer was a flourishing wholesale and retail dry goods operation. By 1900, Edward had left the business to become a whiskey distiller, though this endeavor likely failed since he was working as a traveling salesman in Illinois by 1910.

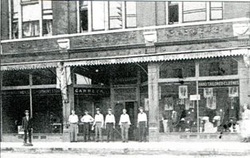

Mann Brothers Department Store, circa 1890

Mann Brothers Department Store, circa 1890

Abraham Mann came to Henderson in 1870, initially working as a store clerk. In 1872, he opened his own store and was joined by his brother Isaac the following year. Their brother Fred joined them in 1880. The Mann Brothers Department Store expanded over the years, eventually growing into a large three-story building downtown. After Abraham and Isaac died in the first decade of the 20th century, their sons took over the business. A 1909 feature in the local newspaper called the store, which employed 62 people at the time, “the largest and most progressive mercantile house in the city and probably in western Kentucky.” Yet the store would not survive the early years of the Great Depression, closing in 1929.

Many of these German Jews who moved to Henderson during the years after the Civil War had a profound impact on the local Jewish community. Moses Heilbronner left Prussia in 1856 and lived in Pennsylvania before moving to Henderson by 1870. Initially working as a store clerk, Heilbronner later opened a grocery store, which he ran until he retired in the early 1920s. Heilbronner would lead religious services for the Henderson Jewish community for over 40 years. Brothers Henry and Morris Baldauf moved to Henderson in the early 1870s, opening a dry goods store. The business partners were very close, with both of their large families sharing the same house. In addition to their successful store, the Baldauf brothers also owned real estate in town, which would become very useful once the local Jewish community established a congregation. Morris' son Julius opened a drug store by 1893, which remained in business until his death in 1926.

Many of these German Jews who moved to Henderson during the years after the Civil War had a profound impact on the local Jewish community. Moses Heilbronner left Prussia in 1856 and lived in Pennsylvania before moving to Henderson by 1870. Initially working as a store clerk, Heilbronner later opened a grocery store, which he ran until he retired in the early 1920s. Heilbronner would lead religious services for the Henderson Jewish community for over 40 years. Brothers Henry and Morris Baldauf moved to Henderson in the early 1870s, opening a dry goods store. The business partners were very close, with both of their large families sharing the same house. In addition to their successful store, the Baldauf brothers also owned real estate in town, which would become very useful once the local Jewish community established a congregation. Morris' son Julius opened a drug store by 1893, which remained in business until his death in 1926.

Mt. Pisgah, Henderson's Jewish cemetery

Mt. Pisgah, Henderson's Jewish cemetery

Organized Jewish Life in Henderson

By 1878, an estimated 79 Jews lived in Henderson, mostly merchants who were German immigrants. Around this time, local Jews began to meet together in rented rooms and private homes for religious services on the High Holidays. Manuel Strong held religious school classes in his store for the Jewish children in town. It was the women of the community who first pushed Henderson Jews to organize. In 1884, Hannah Oberdorfer, the widow of Simon, called together Jennie Heilbronner, Cecelia Oberdorfer, and Bertha Mann to establish the Hebrew Ladies Auxiliary Society. When it was formally incorporated the following year, the society’s stated purposes were to establish a religious school, “provide and maintain a house of worship,” and to acquire land for a cemetery. The ultimate mission of the group was “the promotion of the Jewish religion.” Hannah Oberdorfer served as the first president of the group, which soon set about raising money to purchase land for a cemetery. They received pledges from 23 different people, raising $530 in all. In 1885, they used these funds to purchase land for a cemetery, which they named Mt. Pisgah, just east of town. Rabbi Elgin from Evansville, Indiana, led a consecration ceremony for the cemetery in 1886.

In 1887, Henderson Jews finally established a formal congregation, which they named Adas Israel (Congregation of Israel). During the congregation’s early years, members met for services above Beugger’s Bakery on Main Street and later in Liederkranz Hall. Moses Heilbronner led services for the fledgling congregation from its beginning. Morris Baldauf started a religious school that met in a little brick room he had rented. The Baldauf brothers pushed Adas Israel to construct a synagogue, offering to donate land to the congregation for that purpose. Morris and Henry donated a lot on the corner of Alves and Center Streets with the stipulation that the congregation incur no debt in constructing the synagogue. The membership soon set out to raise money to build a house of worship.

In 1891, they held a cornerstone laying ceremony that drew many local non-Jews as well as Jews from Evansville, Louisville, and Owensboro. Rabbi Glueck of Owensboro spoke during the ceremony, as did Leo Franklin, a student at the Hebrew Union College seminary in Cincinnati. Isaac Mann, Edward Oberdorfer and Peter Geibel headed the building committee. The synagogue was completed and dedicated in 1892 in a ceremony featuring Rabbi Isaac Rypins of Evansville’s Reform congregation.

The synagogue was Reform in design and even featured an organ. Herman Schlesinger was president of Adas Israel at the time of the dedication. A local Christian minister, James Vernon, took part in the dedication as well. He had been invited but had to miss the earlier cornerstone laying ceremony since he was out of the country at the time. Instead, he wrote a letter that was read at the ceremony praising Jews for their contributions to civilization. Vernon argued that Jews had a natural instinct to support democracy, proclaiming that “in the synagogue the Jew is always a Jew; outside of it he is always a loyal, enthusiastic and orderly American citizen.” After listing famous Jews throughout history, Vernon noted “the history of our city’s noblest charity cannot be written without the names of Baldauf and Oberdorfer.”

By 1878, an estimated 79 Jews lived in Henderson, mostly merchants who were German immigrants. Around this time, local Jews began to meet together in rented rooms and private homes for religious services on the High Holidays. Manuel Strong held religious school classes in his store for the Jewish children in town. It was the women of the community who first pushed Henderson Jews to organize. In 1884, Hannah Oberdorfer, the widow of Simon, called together Jennie Heilbronner, Cecelia Oberdorfer, and Bertha Mann to establish the Hebrew Ladies Auxiliary Society. When it was formally incorporated the following year, the society’s stated purposes were to establish a religious school, “provide and maintain a house of worship,” and to acquire land for a cemetery. The ultimate mission of the group was “the promotion of the Jewish religion.” Hannah Oberdorfer served as the first president of the group, which soon set about raising money to purchase land for a cemetery. They received pledges from 23 different people, raising $530 in all. In 1885, they used these funds to purchase land for a cemetery, which they named Mt. Pisgah, just east of town. Rabbi Elgin from Evansville, Indiana, led a consecration ceremony for the cemetery in 1886.

In 1887, Henderson Jews finally established a formal congregation, which they named Adas Israel (Congregation of Israel). During the congregation’s early years, members met for services above Beugger’s Bakery on Main Street and later in Liederkranz Hall. Moses Heilbronner led services for the fledgling congregation from its beginning. Morris Baldauf started a religious school that met in a little brick room he had rented. The Baldauf brothers pushed Adas Israel to construct a synagogue, offering to donate land to the congregation for that purpose. Morris and Henry donated a lot on the corner of Alves and Center Streets with the stipulation that the congregation incur no debt in constructing the synagogue. The membership soon set out to raise money to build a house of worship.

In 1891, they held a cornerstone laying ceremony that drew many local non-Jews as well as Jews from Evansville, Louisville, and Owensboro. Rabbi Glueck of Owensboro spoke during the ceremony, as did Leo Franklin, a student at the Hebrew Union College seminary in Cincinnati. Isaac Mann, Edward Oberdorfer and Peter Geibel headed the building committee. The synagogue was completed and dedicated in 1892 in a ceremony featuring Rabbi Isaac Rypins of Evansville’s Reform congregation.

The synagogue was Reform in design and even featured an organ. Herman Schlesinger was president of Adas Israel at the time of the dedication. A local Christian minister, James Vernon, took part in the dedication as well. He had been invited but had to miss the earlier cornerstone laying ceremony since he was out of the country at the time. Instead, he wrote a letter that was read at the ceremony praising Jews for their contributions to civilization. Vernon argued that Jews had a natural instinct to support democracy, proclaiming that “in the synagogue the Jew is always a Jew; outside of it he is always a loyal, enthusiastic and orderly American citizen.” After listing famous Jews throughout history, Vernon noted “the history of our city’s noblest charity cannot be written without the names of Baldauf and Oberdorfer.”

Adas Israel' synagogue, completed in 1892.

Adas Israel' synagogue, completed in 1892. Photo courtesy of the Henderson Public Library.

Civic Engagement

Reverend Vernon’s comments for the dedication ceremony reflected the prominent role Henderson’s relatively small number of Jews played in the town’s economic and civic life. When local businessmen created the Henderson Building and Loan Association in 1874, which offered loans to those building homes, Isaac Mann, Peter Geibel, and F.P. Geibel served as directors. Edward Oberdorfer and Maurice Baldauf were among those involved in a similar company in 1877. The 1889 city directory shows that Jewish merchants dominated the local dry goods business at the time, owning most of Henderson’s largest and most successful stores. They also served in many civic positions. Oberdorfer was appointed to the city council by the mayor in 1892. Isaac Mann was elected to the city council in 1894, and later to the Board of Tax Supervisors. Peter Geibel was elected city water commissioner in 1894. Nathan Oberdorfer and Moses Heilbronner both served on the local school board. These successful Jewish businessmen were part of the small group of local leaders who ran the city during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Early 20th Century

By 1905, about 150 Jews lived in Henderson. The local Jewish community was bolstered by the arrival of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. Most of these new arrivals eventually followed the pattern set by the earlier German Jews, establishing retail stores in downtown Henderson, although some started out by peddling. Sam Stone, a native of Odessa, Russia, lived in Salt Lake City, Denver, and New York before moving to Henderson in the early 1910s. He settled in Kentucky because his wife Mollie’s sister Ida was married to Morris Silverman, who had owned a dry goods store in Henderson since 1905. Stone was a shoe repairer, and operated a small shop in the back of Silverman’s dry goods store for four years after arriving. Stone opened his own stand-alone shop in 1917. While the Silvermans sold their store in 1927 and moved to Florida, the Stones remained in Henderson.

Jacob Simon left Lithuania in 1910 and came directly to Henderson where his brother Ben lived. Soon after he arrived in Kentucky, Jacob set out peddling, carrying a pack filled with needles, thread, and fabric to the farms in the area. Not knowing much English, Simon found it hard initially to gain the trust of his customers. But over time, they came to look forward to when Simon would come and would let him stay the night in their homes. According to Simon, “the children began to look forward to my visits as if I were Santa Claus.” After four years, Simon opened a small dry goods store in Henderson, though he sold it in 1918 when he joined the U.S. Army during World War I. Right after the war, he joined a dry goods business owned by Arnold Kahn, buying out his partner in 1920. Renaming the store Simon’s, Jacob would travel to Louisville to buy merchandise. On one trip he met his future wife Goldie Grossman, the daughter of one of his suppliers.

Ben Bernstein, a Roumanian immigrant, started out peddling in Kentucky before opening a small store in Henderson in 1910. He and his wife Mae moved to Hopkinsville briefly in the mid-1920s, but soon returned to Henderson where they bought the Interstate Store, which they renamed Bernstein’s. Ben became very active in local charity efforts, helping to organize the Salvation Army and spending three terms as its chairman. He also served on the board of the regional YMCA, and was even chairman of the group’s World Service Committee, which oversaw its overseas missionary work. Mae Bernstein was vice-president of the city’s Public Welfare Board and spent more than twenty years on the board of the local Red Cross.

By 1900, Adas Israel had 21 members. With only $600 in annual dues income, the congregation could not afford a rabbi, and Moses Heilbronner continued to serve as lay leader during weekly Friday night services. Adas Israel joined the Reform Union of American Hebrew Congregations by 1905. Despite the congregation’s Reform affiliation, the membership was a mix of native-born Americans and immigrants. Two families kept strict kosher, bringing in kosher meat from Evansville, Indiana. Of the nine Adas Israel officers and board members in 1900, three were American-born, four were German immigrants, while two came from Russian Poland. All but one owned their own business, mostly dry goods and grocery stores. The congregation enjoyed steady growth during the early years of the 20th century, reaching 30 members by 1905. Adas Israel had 24 children in its religious school in 1907. Yet Adas Israel never grew larger than this. For the next half century, the congregation slowly declined in size. By 1935, only 20 families belonged to Henderson’s lone Jewish congregation.

Although it was small, Adas Israel was quite active. Heilbronner continued to lead the weekly Friday night services until he died in 1925. Afterward, Sam Mayer, Henry Levy and Moses’s son Solomon Heilbronner would lead them. Adas Israel also began to bring in students rabbis from Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati after 1925. That same year, Rabbi Joseph Rauch of Adath Israel in Louisville would visit Henderson once a month to lead services. Celeste Levy oversaw the weekly Sunday school for the 28-member congregation in 1925. In 1919, the women of the congregation established a formal Sisterhood, which took over the functions of the earlier Ladies Auxiliary Society. During World War II, the Sisterhood served Jewish soldiers stationed at Camp Breckenridge, offering hospitality and social events. Mae Bernstein headed this effort and served on the Jewish Welfare Board. Adas Israel enjoyed a warm relationship with local churches, allowing two different Baptist congregations to use the temple when their buildings were damaged.

Although Adas Israel was the town’s only Jewish religious institution, there was a Jewish social organization for a brief time. In 1890, a group of young Jewish men established the Harmony Club. By 1900, the club had fifteen members, but no permanent meeting place. The group was still active in 1907, but had dissolved by 1912.

Despite this activity, the Jewish community declined over the first half of the 20th century. In 1908, Morris Baldauf reported to the Industrial Removal Office in New York that Henderson had 58 Jewish adults and 69 children. But by 1937, only 88 Jews lived in Henderson; in 1942, this number had dipped to 70 people. Adas Israel had only 18 dues paying members in 1945.

Reverend Vernon’s comments for the dedication ceremony reflected the prominent role Henderson’s relatively small number of Jews played in the town’s economic and civic life. When local businessmen created the Henderson Building and Loan Association in 1874, which offered loans to those building homes, Isaac Mann, Peter Geibel, and F.P. Geibel served as directors. Edward Oberdorfer and Maurice Baldauf were among those involved in a similar company in 1877. The 1889 city directory shows that Jewish merchants dominated the local dry goods business at the time, owning most of Henderson’s largest and most successful stores. They also served in many civic positions. Oberdorfer was appointed to the city council by the mayor in 1892. Isaac Mann was elected to the city council in 1894, and later to the Board of Tax Supervisors. Peter Geibel was elected city water commissioner in 1894. Nathan Oberdorfer and Moses Heilbronner both served on the local school board. These successful Jewish businessmen were part of the small group of local leaders who ran the city during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Early 20th Century

By 1905, about 150 Jews lived in Henderson. The local Jewish community was bolstered by the arrival of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. Most of these new arrivals eventually followed the pattern set by the earlier German Jews, establishing retail stores in downtown Henderson, although some started out by peddling. Sam Stone, a native of Odessa, Russia, lived in Salt Lake City, Denver, and New York before moving to Henderson in the early 1910s. He settled in Kentucky because his wife Mollie’s sister Ida was married to Morris Silverman, who had owned a dry goods store in Henderson since 1905. Stone was a shoe repairer, and operated a small shop in the back of Silverman’s dry goods store for four years after arriving. Stone opened his own stand-alone shop in 1917. While the Silvermans sold their store in 1927 and moved to Florida, the Stones remained in Henderson.

Jacob Simon left Lithuania in 1910 and came directly to Henderson where his brother Ben lived. Soon after he arrived in Kentucky, Jacob set out peddling, carrying a pack filled with needles, thread, and fabric to the farms in the area. Not knowing much English, Simon found it hard initially to gain the trust of his customers. But over time, they came to look forward to when Simon would come and would let him stay the night in their homes. According to Simon, “the children began to look forward to my visits as if I were Santa Claus.” After four years, Simon opened a small dry goods store in Henderson, though he sold it in 1918 when he joined the U.S. Army during World War I. Right after the war, he joined a dry goods business owned by Arnold Kahn, buying out his partner in 1920. Renaming the store Simon’s, Jacob would travel to Louisville to buy merchandise. On one trip he met his future wife Goldie Grossman, the daughter of one of his suppliers.

Ben Bernstein, a Roumanian immigrant, started out peddling in Kentucky before opening a small store in Henderson in 1910. He and his wife Mae moved to Hopkinsville briefly in the mid-1920s, but soon returned to Henderson where they bought the Interstate Store, which they renamed Bernstein’s. Ben became very active in local charity efforts, helping to organize the Salvation Army and spending three terms as its chairman. He also served on the board of the regional YMCA, and was even chairman of the group’s World Service Committee, which oversaw its overseas missionary work. Mae Bernstein was vice-president of the city’s Public Welfare Board and spent more than twenty years on the board of the local Red Cross.

By 1900, Adas Israel had 21 members. With only $600 in annual dues income, the congregation could not afford a rabbi, and Moses Heilbronner continued to serve as lay leader during weekly Friday night services. Adas Israel joined the Reform Union of American Hebrew Congregations by 1905. Despite the congregation’s Reform affiliation, the membership was a mix of native-born Americans and immigrants. Two families kept strict kosher, bringing in kosher meat from Evansville, Indiana. Of the nine Adas Israel officers and board members in 1900, three were American-born, four were German immigrants, while two came from Russian Poland. All but one owned their own business, mostly dry goods and grocery stores. The congregation enjoyed steady growth during the early years of the 20th century, reaching 30 members by 1905. Adas Israel had 24 children in its religious school in 1907. Yet Adas Israel never grew larger than this. For the next half century, the congregation slowly declined in size. By 1935, only 20 families belonged to Henderson’s lone Jewish congregation.

Although it was small, Adas Israel was quite active. Heilbronner continued to lead the weekly Friday night services until he died in 1925. Afterward, Sam Mayer, Henry Levy and Moses’s son Solomon Heilbronner would lead them. Adas Israel also began to bring in students rabbis from Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati after 1925. That same year, Rabbi Joseph Rauch of Adath Israel in Louisville would visit Henderson once a month to lead services. Celeste Levy oversaw the weekly Sunday school for the 28-member congregation in 1925. In 1919, the women of the congregation established a formal Sisterhood, which took over the functions of the earlier Ladies Auxiliary Society. During World War II, the Sisterhood served Jewish soldiers stationed at Camp Breckenridge, offering hospitality and social events. Mae Bernstein headed this effort and served on the Jewish Welfare Board. Adas Israel enjoyed a warm relationship with local churches, allowing two different Baptist congregations to use the temple when their buildings were damaged.

Although Adas Israel was the town’s only Jewish religious institution, there was a Jewish social organization for a brief time. In 1890, a group of young Jewish men established the Harmony Club. By 1900, the club had fifteen members, but no permanent meeting place. The group was still active in 1907, but had dissolved by 1912.

Despite this activity, the Jewish community declined over the first half of the 20th century. In 1908, Morris Baldauf reported to the Industrial Removal Office in New York that Henderson had 58 Jewish adults and 69 children. But by 1937, only 88 Jews lived in Henderson; in 1942, this number had dipped to 70 people. Adas Israel had only 18 dues paying members in 1945.

Kraver Theater. Photo courtesy of the Henderson Public Library.

Kraver Theater. Photo courtesy of the Henderson Public Library.

Active Citizens

Although their numbers were in decline, Jews continued to make a significant mark on Henderson. Henry Kraver came to Henderson in the 1890s, becoming a whiskey distiller and later the president of the First National Bank. In 1929, Kraver constructed a large downtown building intended to be used as a Montgomery Ward store. But when the store closed due to the Depression in 1931, Kraver decided to convert it into a grand theater that showed movies and hosted vaudeville acts. Opened in 1935, the Kraver Theater remained a downtown landmark for over 40 years. Although Kraver died in 1938, his theater remained in business until 1976. Solomon Heilbronner became an influential lawyer in Henderson. As part of the Republican Good Government ticket, Heilbronner served four years as city attorney. He also spent over 30 years as secretary of the Kentucky State Bar Association. In a short history of the Henderson Jewish community written in 1942, Heilbronner declared that Henderson Jews had always worked to improve their town and “taken leading roles in every humanitarian work and civic project.”

Although their numbers were in decline, Jews continued to make a significant mark on Henderson. Henry Kraver came to Henderson in the 1890s, becoming a whiskey distiller and later the president of the First National Bank. In 1929, Kraver constructed a large downtown building intended to be used as a Montgomery Ward store. But when the store closed due to the Depression in 1931, Kraver decided to convert it into a grand theater that showed movies and hosted vaudeville acts. Opened in 1935, the Kraver Theater remained a downtown landmark for over 40 years. Although Kraver died in 1938, his theater remained in business until 1976. Solomon Heilbronner became an influential lawyer in Henderson. As part of the Republican Good Government ticket, Heilbronner served four years as city attorney. He also spent over 30 years as secretary of the Kentucky State Bar Association. In a short history of the Henderson Jewish community written in 1942, Heilbronner declared that Henderson Jews had always worked to improve their town and “taken leading roles in every humanitarian work and civic project.”

Simon's Shoes remains in business today.

Simon's Shoes remains in business today.

Kraver and Heilbronner were exceptions as most Henderson Jews still owned retail stores. Increasingly, it was the second and third generations who continued to run family businesses. Soon after the Mann Brothers Department Store closed in 1929, Abraham Mann’s son Clarence and his wife Esther opened the much smaller Mann’s Ready to Wear. After Clarence and his son Clarence Jr. both died in 1950, Esther continued to run the business with her widowed daughter-in-law, Jean Berger. Esther, who ran the store for over 50 years, remained active in the business up until her death in 1985. Jean Berger ran Mann’s until she finally closed the business in 1995. Ben Bernstein’s son Sol joined the family store after returning from World War II. In 1949, the business moved into a new building and became Bernstein’s Men’s and Boys’ Store. When Sol decided to pursue his interest in journalism and broadcasting, working for the Henderson Gleaner newspaper and hosting a local radio show, his wife Shirley ran the store. Their son Jerry joined his mother in the business in 1969, taking it over a few years later. Jerry Bernstein decided to close the store in 2009, the same year he was given the Downtown Henderson Project’s Heart of Henderson Award for his years of service to the city. Jake and Goldie Simon’s son Larry joined Simon’s store in 1949. While the store had always sold general merchandise, Larry convinced his parents to focus exclusively on shoes in the early 1960s. Simon’s Shoe Store is still in business today, run by Larry’s son Bruce Simon. Simon’s, which draws customers from as far away as 100 miles with its personal service and wide selection of sizes, is the last Jewish-owned store in Henderson.

The former synagogue of Adas Israel

The former synagogue of Adas Israel

The Community Declines

For the 50th anniversary of its temple in 1942, Adas Israel held a rededication service. In 1950, they completely remodeled the interior of the building, even though they had fewer than 20 member families at the time. Adas Israel often struggled to afford its twice monthly student rabbinic visits; the Sisterhood covered half of the cost. Nevertheless, the congregation continued to hold weekly services with lay leaders when student rabbis were not there. The worship service was classical Reform in style with minimal Hebrew; one student rabbi noted in 1953 that the members “regard Kiddush and candle lighting as Orthodox.” By the early 1950s, there were not enough children to have a Sunday school as the few that remained went to Evansville for religious instruction. In 1953, they cut back their student rabbi visits to only once a month, and a few years later only brought in student rabbis to lead High Holiday services. In 1958, last their student rabbi reported that the congregation was almost entirely over the age of 65 since “most of their children have left for bigger cities.” “There is so little young blood in this community” another student rabbi wrote. In 1959, Adas Israel, with only 15 members, decided they could no longer afford a student rabbi and planned to have lay-led services for the High Holidays.

By 1965, the congregation had only five families, and the cost of heating and maintaining their building was becoming prohibitive. The remaining members decided to sell the temple and disband the congregation. In 1966, a local church bought the building. The handful of Jewish families left in Henderson joined the congregation across the river in Evansville, Indiana.

For the 50th anniversary of its temple in 1942, Adas Israel held a rededication service. In 1950, they completely remodeled the interior of the building, even though they had fewer than 20 member families at the time. Adas Israel often struggled to afford its twice monthly student rabbinic visits; the Sisterhood covered half of the cost. Nevertheless, the congregation continued to hold weekly services with lay leaders when student rabbis were not there. The worship service was classical Reform in style with minimal Hebrew; one student rabbi noted in 1953 that the members “regard Kiddush and candle lighting as Orthodox.” By the early 1950s, there were not enough children to have a Sunday school as the few that remained went to Evansville for religious instruction. In 1953, they cut back their student rabbi visits to only once a month, and a few years later only brought in student rabbis to lead High Holiday services. In 1958, last their student rabbi reported that the congregation was almost entirely over the age of 65 since “most of their children have left for bigger cities.” “There is so little young blood in this community” another student rabbi wrote. In 1959, Adas Israel, with only 15 members, decided they could no longer afford a student rabbi and planned to have lay-led services for the High Holidays.

By 1965, the congregation had only five families, and the cost of heating and maintaining their building was becoming prohibitive. The remaining members decided to sell the temple and disband the congregation. In 1966, a local church bought the building. The handful of Jewish families left in Henderson joined the congregation across the river in Evansville, Indiana.

The Jewish Community in Henderson Today

Today, only a few Jews live in Henderson, while the only remaining vestiges of an organized Jewish community are the old synagogue, now a church, and the cemetery. Though he was writing in 1925, a local journalist could have been summing up the 150-year history of Jews in Henderson when he wrote: “peacefully, quietly the Congregation of Adas Israel has gone through the years worshiping the God of Israel as they see fit, diligent in business, zealous in religion, active in all civic affairs, and lending valuable aid in philanthropy and charity.”