Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Lexington, Kentucky

Lexington: Historical Overview

|

Lexington, the capital of Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region, was first settled in 1779. After the Revolutionary War, the town developed as a nexus of several frontier roads and became the fastest growing settlement in Kentucky. By the time Lexington was formally incorporated in 1831, it already had all the trappings of a city, including thriving businesses and manufacturing, lavish homes, theaters, and even a college. With the invention of the steamboat, Lexington was soon outstripped by nearby cities like Louisville and Cincinnati, which were located on the Ohio River. But the arrival of the railroad in the 1830s and 1840s ensured that landlocked Lexington would continue to be a major center for trade and commerce.

Jews have been part of Lexington's history since 1816, and remain an important part of the city's life today. |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Lexington

Benjamin Gratz

Benjamin Gratz

Early Jewish Settlers

The first Jewish settler in Lexington was a man named Salomon, who came to the growing city in 1816 to be the cashier at the recently opened branch of the Bank of the United States. While we don’t know his first name, his most lasting legacy was his bringing Benjamin Gratz to Lexington. Scion of a prominent Jewish family in Philadelphia, Gratz moved to Lexington in 1819. His father, Michael Gratz, owned a great deal of land in Kentucky at the time. Benjamin became one of Lexington’s most prominent citizens during the 19th century. He was one of the founders of the Lexington and Ohio Railroad Company, the state’s first railroad, in 1830. He served as the company’s second president. Their efforts to connect Lexington to the state capital of Frankfort and Louisville helped insure the economic prominence of their city. Gratz served on Lexington’s first city council in 1832 and was a director of the first two banks established in the city. He spent 63 years as a trustee of the city’s Transylvania University.

Gratz had an array of other economic interests, owning a store and a hemp manufacturing business. A loyal unionist, Gratz used his home as a cook house and commissary for Federal troops during the Civil War. After the war, he and his son Henry created Gratz Park from land they leased from Transylvania University. Benjamin’s son Anderson later bought the land and donated it to the city as a permanent park. Benjamin Gratz remained in Lexington until his death in 1884, though he had little connection to the city’s nascent Jewish community. Gratz intermarried and raised his children as Christians. However, Gratz would attend High Holiday services when they were held in Lexington later in his life.

The first Jewish settler in Lexington was a man named Salomon, who came to the growing city in 1816 to be the cashier at the recently opened branch of the Bank of the United States. While we don’t know his first name, his most lasting legacy was his bringing Benjamin Gratz to Lexington. Scion of a prominent Jewish family in Philadelphia, Gratz moved to Lexington in 1819. His father, Michael Gratz, owned a great deal of land in Kentucky at the time. Benjamin became one of Lexington’s most prominent citizens during the 19th century. He was one of the founders of the Lexington and Ohio Railroad Company, the state’s first railroad, in 1830. He served as the company’s second president. Their efforts to connect Lexington to the state capital of Frankfort and Louisville helped insure the economic prominence of their city. Gratz served on Lexington’s first city council in 1832 and was a director of the first two banks established in the city. He spent 63 years as a trustee of the city’s Transylvania University.

Gratz had an array of other economic interests, owning a store and a hemp manufacturing business. A loyal unionist, Gratz used his home as a cook house and commissary for Federal troops during the Civil War. After the war, he and his son Henry created Gratz Park from land they leased from Transylvania University. Benjamin’s son Anderson later bought the land and donated it to the city as a permanent park. Benjamin Gratz remained in Lexington until his death in 1884, though he had little connection to the city’s nascent Jewish community. Gratz intermarried and raised his children as Christians. However, Gratz would attend High Holiday services when they were held in Lexington later in his life.

Store ads from 1878

Store ads from 1878

The Late 19th Century

There wasn’t a significant Jewish population in Lexington until around the time of the Civil War. By the end of the war, about 20 Jewish families lived in the city. German-born Henry Loevenhart first moved to Lexington in 1857, having arrived in the U.S. six years earlier. After apprenticing as a watchmaker, Loevenhart repaired watches and sold goods to Union soldiers during the war. After short periods in Nashville, Indianapolis, and Ottumwa, Iowa, Henry and his brother Lee moved back to Lexington in 1867 and opened a small clothing store on Main Street. H. & L. Loevenhart grew over the years, moving into a new larger building in 1878. The store remained in business until 1914. Louis and Gus Straus opened a clothing store in Lexington by 1870. In 1882, a local writer claimed that theirs was one of the largest retail businesses in the city. After success in the retail business, the brothers later got involved in raising racehorses, not uncommon in the Bluegrass Region. Louis also served as president of Lexington’s Central Bank.

Perhaps the most prominent Lexington Jew in the late 19th century was Moses Kaufman. Born in Bavaria, Kaufman lived in Cincinnati before moving to Lexington in 1867 and opening a clothing store. Kaufman became very active in local politics, winning election to the city council in 1879. While in office, Kaufman was a leader of the reform faction that challenged boss rule in Lexington. Kaufman and his allies succeeded in having the mayor be elected by popular vote. He also led the way in installing a telephone fire alarm system in 1880. In all, Kaufman served seventeen years on the city council, many of them as its president. Active in the Democratic Party, Kaufman was elected to the state legislature in 1896. Later, he served four years as city treasurer and eight as city auditor. In 1915, President Woodrow Wilson appointed Kaufman as postmaster for Lexington, a position he held for nine years. When Kaufman died in 1924, the local newspaper called him “one of the best known men in Lexington” and ran many encomiums in his honor.

There wasn’t a significant Jewish population in Lexington until around the time of the Civil War. By the end of the war, about 20 Jewish families lived in the city. German-born Henry Loevenhart first moved to Lexington in 1857, having arrived in the U.S. six years earlier. After apprenticing as a watchmaker, Loevenhart repaired watches and sold goods to Union soldiers during the war. After short periods in Nashville, Indianapolis, and Ottumwa, Iowa, Henry and his brother Lee moved back to Lexington in 1867 and opened a small clothing store on Main Street. H. & L. Loevenhart grew over the years, moving into a new larger building in 1878. The store remained in business until 1914. Louis and Gus Straus opened a clothing store in Lexington by 1870. In 1882, a local writer claimed that theirs was one of the largest retail businesses in the city. After success in the retail business, the brothers later got involved in raising racehorses, not uncommon in the Bluegrass Region. Louis also served as president of Lexington’s Central Bank.

Perhaps the most prominent Lexington Jew in the late 19th century was Moses Kaufman. Born in Bavaria, Kaufman lived in Cincinnati before moving to Lexington in 1867 and opening a clothing store. Kaufman became very active in local politics, winning election to the city council in 1879. While in office, Kaufman was a leader of the reform faction that challenged boss rule in Lexington. Kaufman and his allies succeeded in having the mayor be elected by popular vote. He also led the way in installing a telephone fire alarm system in 1880. In all, Kaufman served seventeen years on the city council, many of them as its president. Active in the Democratic Party, Kaufman was elected to the state legislature in 1896. Later, he served four years as city treasurer and eight as city auditor. In 1915, President Woodrow Wilson appointed Kaufman as postmaster for Lexington, a position he held for nine years. When Kaufman died in 1924, the local newspaper called him “one of the best known men in Lexington” and ran many encomiums in his honor.

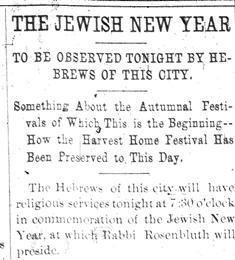

Kentucky Leader

, October 2, 1891

Kentucky Leader

, October 2, 1891

Organized Jewish Life in Lexington

The Lexington newspaper also noted that Moses Kaufman was “recognized as the leader of the Hebrew people of the city.” Not long after his arrival in the city, the Jews of Lexington began to organize as a community. As early as 1864, Lexington Jews were meeting together in private homes for the High Holidays each year. In 1872, 28 Jewish men established the Spinoza Burial Society, named after the Jewish philosopher, and purchased land for a cemetery. Most of these founders, over 80%, owned their own businesses, mostly retail stores. Julius Speyer was the first president of the Spinoza Burial Society. In 1885, they sold the cemetery land since it was too far outside the city and hard to get to. They bought a new plot of land in the city cemetery and moved all of the graves to this new Jewish section.

By 1877, the Lexington Jewish community was estimated at 140 people. That year, there was an effort to establish a formal congregation. According to the minutes of the burial society, the group concluded that “whereas all the Israelites are also members of the Spinoza Association, and whereas it an unheard of thing and contrary to all custom…that a Congregation and a Burial Society, composed of the same members, should exist apart from each other in the same place…that the Spinoza Association and the congregation should be merged.” The new group, called the Spinoza Association and Congregation, rented a building on the corner of Short and Limestone Streets which they used as a synagogue. In 1878, they hired Reverend M. Laski to serve as their chazzan, teacher, and shochet. Laski gave a sermon in English during a special Sukkhot service that year. After the congregation refused his salary demands, Laski left Lexington after only one month. By 1882, the congregation met for lay led services each Friday night and Saturday morning at Bradley’s Hall.

Lexington’s congregation soon dissipated, yet local Jews continued to hold High Holiday services each year. In 1890, the local newspaper reported that Lexington Jews held Yom Kippur services “under the direction of Rev. Isaac Sosland of Louisville” in the rooms of the Young Men’s Republican Club above the city’s opera house. By 1891, two different groups of Jews were meeting for the High Holidays, one Reform and the other Orthodox. Neither had a formal congregation or permanent synagogue, while both groups brought in visiting spiritual leaders for the holiday services. In 1898, the Reform group met at the Central Christian Church for the High Holidays, using the church’s organist and choir during the service. By the turn of the century, the Orthodox group seemed to be stronger. In 1900, they held two days of Rosh Hashanah services at the Odd Fellows Hall led by Rabbi M.J. Samuels of Cincinnati. The group informed the Lexington Leader that it was inviting “all the Jews of the city, both orthodox and reformed, to be present.” The following year, the Reform group held lay-led High Holiday services at the home of Henry Loevenhart.

The Orthodox group, largely made up of recent immigrants from Lithuania, had begun meeting together informally for regular services at the Merrick Lodge Hall in 1899. They also held daily minyans at the various downtown stores run by the members. In addition to Orthodox worship, the group, known as the Ohavay Zion Society by 1903, also focused on helping other Jews in need. In 1900, after Rosh Hashanah services, the group discussed how to help 200 Armenian Jewish refugees who had just arrived in New York City. In 1903, they held a special meeting to discuss the plight of Russian Jews after the Kishinev pogrom. They created a committee that raised $50 for victims of the pogroms. The Ohavay Zion Society met for the High Holidays at the Odd Fellows Hall, though a scheduling conflict in 1911 convinced the group to officially incorporate and acquire a permanent home. That year, the society was holding Yom Kippur services when the Odd Fellows demanded the use of their building for a regular meeting. Forced to finish the services at a member’s home, the group finally decided to buy their own synagogue. In 1912, they were chartered as the Ohavay Zion Congregation. Nathan Rogers, a wholesale dry goods merchant, was their first president. The group soon bought the former Maxwell Street Presbyterian Church and turned it into a synagogue. The congregation auctioned off pews to raise money to redecorate the building. They had to remove the church organ, among other things, in order to make the building into an Orthodox synagogue. Ohavay Zion finally dedicated its synagogue in 1914. Although the congregation was nominally Orthodox, Ohavay Zion had mixed seating from the beginning. One side section of seats was reserved for men, while the other side was for women only. Men and women could sit together in the center section. This compromise seating arrangement reflected the religious diversity within Lexington’s Orthodox congregation.

ing donation from prominent Cincinnati businessman Leo Marks. Marks, who had grown up in Lexington, made the donation in honor of his father Julius Marks, a longtime leader of the local Jewish community. The congregation was able to raise another $25,000 to match Marks’ donation, and dedicated their new temple on Ashland Avenue in 1926. The congregation grew after moving into its new building, increasing from 42 families in 1920 to 100 in 1940.

The Lexington newspaper also noted that Moses Kaufman was “recognized as the leader of the Hebrew people of the city.” Not long after his arrival in the city, the Jews of Lexington began to organize as a community. As early as 1864, Lexington Jews were meeting together in private homes for the High Holidays each year. In 1872, 28 Jewish men established the Spinoza Burial Society, named after the Jewish philosopher, and purchased land for a cemetery. Most of these founders, over 80%, owned their own businesses, mostly retail stores. Julius Speyer was the first president of the Spinoza Burial Society. In 1885, they sold the cemetery land since it was too far outside the city and hard to get to. They bought a new plot of land in the city cemetery and moved all of the graves to this new Jewish section.

By 1877, the Lexington Jewish community was estimated at 140 people. That year, there was an effort to establish a formal congregation. According to the minutes of the burial society, the group concluded that “whereas all the Israelites are also members of the Spinoza Association, and whereas it an unheard of thing and contrary to all custom…that a Congregation and a Burial Society, composed of the same members, should exist apart from each other in the same place…that the Spinoza Association and the congregation should be merged.” The new group, called the Spinoza Association and Congregation, rented a building on the corner of Short and Limestone Streets which they used as a synagogue. In 1878, they hired Reverend M. Laski to serve as their chazzan, teacher, and shochet. Laski gave a sermon in English during a special Sukkhot service that year. After the congregation refused his salary demands, Laski left Lexington after only one month. By 1882, the congregation met for lay led services each Friday night and Saturday morning at Bradley’s Hall.

Lexington’s congregation soon dissipated, yet local Jews continued to hold High Holiday services each year. In 1890, the local newspaper reported that Lexington Jews held Yom Kippur services “under the direction of Rev. Isaac Sosland of Louisville” in the rooms of the Young Men’s Republican Club above the city’s opera house. By 1891, two different groups of Jews were meeting for the High Holidays, one Reform and the other Orthodox. Neither had a formal congregation or permanent synagogue, while both groups brought in visiting spiritual leaders for the holiday services. In 1898, the Reform group met at the Central Christian Church for the High Holidays, using the church’s organist and choir during the service. By the turn of the century, the Orthodox group seemed to be stronger. In 1900, they held two days of Rosh Hashanah services at the Odd Fellows Hall led by Rabbi M.J. Samuels of Cincinnati. The group informed the Lexington Leader that it was inviting “all the Jews of the city, both orthodox and reformed, to be present.” The following year, the Reform group held lay-led High Holiday services at the home of Henry Loevenhart.

The Orthodox group, largely made up of recent immigrants from Lithuania, had begun meeting together informally for regular services at the Merrick Lodge Hall in 1899. They also held daily minyans at the various downtown stores run by the members. In addition to Orthodox worship, the group, known as the Ohavay Zion Society by 1903, also focused on helping other Jews in need. In 1900, after Rosh Hashanah services, the group discussed how to help 200 Armenian Jewish refugees who had just arrived in New York City. In 1903, they held a special meeting to discuss the plight of Russian Jews after the Kishinev pogrom. They created a committee that raised $50 for victims of the pogroms. The Ohavay Zion Society met for the High Holidays at the Odd Fellows Hall, though a scheduling conflict in 1911 convinced the group to officially incorporate and acquire a permanent home. That year, the society was holding Yom Kippur services when the Odd Fellows demanded the use of their building for a regular meeting. Forced to finish the services at a member’s home, the group finally decided to buy their own synagogue. In 1912, they were chartered as the Ohavay Zion Congregation. Nathan Rogers, a wholesale dry goods merchant, was their first president. The group soon bought the former Maxwell Street Presbyterian Church and turned it into a synagogue. The congregation auctioned off pews to raise money to redecorate the building. They had to remove the church organ, among other things, in order to make the building into an Orthodox synagogue. Ohavay Zion finally dedicated its synagogue in 1914. Although the congregation was nominally Orthodox, Ohavay Zion had mixed seating from the beginning. One side section of seats was reserved for men, while the other side was for women only. Men and women could sit together in the center section. This compromise seating arrangement reflected the religious diversity within Lexington’s Orthodox congregation.

ing donation from prominent Cincinnati businessman Leo Marks. Marks, who had grown up in Lexington, made the donation in honor of his father Julius Marks, a longtime leader of the local Jewish community. The congregation was able to raise another $25,000 to match Marks’ donation, and dedicated their new temple on Ashland Avenue in 1926. The congregation grew after moving into its new building, increasing from 42 families in 1920 to 100 in 1940.

Ohavey Zion's first synagogue

Ohavey Zion's first synagogue

In 1919, Ohavay Zion hired its first full-time rabbi, Jacob Lowenthal, who also served as shochet and mohel for the congregation. Morris Sherago, a professor at the University of Kentucky, started a religious school around the same time. Their synagogue consisted of a sanctuary and a basement; larger events were often held in rented halls. In the early 1920s, the congregation bought a nearby house, which they remodeled into a social hall and religious school. During its early years, Ohavay Zion had several rabbis, none of whom stayed for very long. The congregation later bought a parsonage close to the synagogue so their rabbi could easily walk to services. When Ohavay Zion was in between rabbis, members would lead services themselves. Harry Gollar, who owned a kosher butcher shop and deli in Lexington, would often lead these services, giving sermons in Yiddish.

In late 1903, Lexington’s Reform Jews decided to establish a formal congregation. Isadore Miller and Fred Lazarus traveled to surrounding towns like Paris, Kentucky to enlist additional members. In December, Rabbi Leo Mannheimer of Chattanooga, described by the Lexington Morning Herald as a “distinguished Jewish priest,” addressed the fledgling congregation. Rabbi Mannheimer agreed to travel to Lexington every other Sunday to lead services. In January, 1904, the group met at the Odd Fellows Hall to officially form Temple Adath Israel; Fred Lazarus was elected as the congregation’s first president. Adath Israel soon hired Rabbi Sam Goldenson, who had just been ordained by Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. The congregation rented a church, which they used as a synagogue. In 1905, Adath Israel, which numbered 35 member families, purchased the building. Although most members were German Jews who had either lived in the U.S. for several decades or were native born, the members of Adath Israel were concerned about the plight of Jews in Russia. In 1905, they created a Hebrew Relief Society to help Russian Jews. Each temple member’s dues were increased $3 in order to fund this cause. Reflecting the relative wealth of the members, they raised $1000 for Jewish relief in 1905.

In late 1903, Lexington’s Reform Jews decided to establish a formal congregation. Isadore Miller and Fred Lazarus traveled to surrounding towns like Paris, Kentucky to enlist additional members. In December, Rabbi Leo Mannheimer of Chattanooga, described by the Lexington Morning Herald as a “distinguished Jewish priest,” addressed the fledgling congregation. Rabbi Mannheimer agreed to travel to Lexington every other Sunday to lead services. In January, 1904, the group met at the Odd Fellows Hall to officially form Temple Adath Israel; Fred Lazarus was elected as the congregation’s first president. Adath Israel soon hired Rabbi Sam Goldenson, who had just been ordained by Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. The congregation rented a church, which they used as a synagogue. In 1905, Adath Israel, which numbered 35 member families, purchased the building. Although most members were German Jews who had either lived in the U.S. for several decades or were native born, the members of Adath Israel were concerned about the plight of Jews in Russia. In 1905, they created a Hebrew Relief Society to help Russian Jews. Each temple member’s dues were increased $3 in order to fund this cause. Reflecting the relative wealth of the members, they raised $1000 for Jewish relief in 1905.

Adath Israel's first synagogue.

Adath Israel's first synagogue. Photo courtesy of Lee Shai Weissbach.

Adath Israel was classical Reform, joining the Union of American Hebrew Congregations by 1910. Soon after the congregation acquired its temple in 1905, the Ladies Auxiliary, which later became the temple sisterhood, donated an organ for use during services. In Adath Israel’s early years, they congregation had several different rabbis, most of whom only stayed for a few years. They would bring in student rabbis from Hebrew Union College when they did not have a full-time rabbi. From 1919 to 1923, the young HUC professor Jacob Rader Marcus served as the congregation’s regular visiting rabbi. In 1924, they hired Rabbi Theodore Lifset as their first full-time spiritual leader in almost a decade. Rabbi Lawrence Kahn replaced him in 1930, though he only stayed in Lexington for two years. Rabbi Milton Grafman, just out of HUC, came to Adath Israel in 1932 and stayed for nine years. In 1925, Adath Israel built a new synagogue with the help of a $25,000 match

Jewish Organizations in Lexington

In addition to the two congregations, Lexington Jews created several other Jewish organizations. A B’nai B’rith Lodge was formed by 1882. This local branch of the national Jewish fraternal society attracted prominent local Jews such as Moses Kaufman and Julius Mark. In 1903, a group of Lexington women established a local chapter of the Council of Jewish Women, which focused on doing charity work in the larger community. Over the years, the CJW worked on a tuberculosis control program with the local health department and started and ran a library located in the Second Street YMCA that served the neighborhood’s poor residents. Later, they also sponsored drug education and theater programs for local public schools. In 1917, the Lexington Jewish community created the Federated Jewish Charities to consolidate and organize local Jewish charities. By 1919, the organization had 70 members and was raising over $1200 annually.

In addition to the two congregations, Lexington Jews created several other Jewish organizations. A B’nai B’rith Lodge was formed by 1882. This local branch of the national Jewish fraternal society attracted prominent local Jews such as Moses Kaufman and Julius Mark. In 1903, a group of Lexington women established a local chapter of the Council of Jewish Women, which focused on doing charity work in the larger community. Over the years, the CJW worked on a tuberculosis control program with the local health department and started and ran a library located in the Second Street YMCA that served the neighborhood’s poor residents. Later, they also sponsored drug education and theater programs for local public schools. In 1917, the Lexington Jewish community created the Federated Jewish Charities to consolidate and organize local Jewish charities. By 1919, the organization had 70 members and was raising over $1200 annually.

Adath Israel's 1926 synagogue

Adath Israel's 1926 synagogue

Jewish Businesses in Lexington

The Lexington Jewish community was growing during the early 20th century, reaching an estimated 750 people by 1927. At the time, most Lexington Jews were still in business. Several Jewish-owned stores established in the 19th century continued well into the 20th century. The Kaufman Clothing Company, which had been founded by Moses Kaufman in 1867, was bought by Phil Strauss in 1900. Strauss later brought his sons Robert and James into the business. After Robert died in 1953, James ran it by himself. When James retired in 1963, his son James W. Strauss took over the clothing store, and operated it well past its 100th anniversary. In 1910, Dolph Wile and Simon Wolf bought a 20-year-old department store and changed its name to the Wolf Wile Company. After Wolf died in 1921, the Wile family ran the business. Dolph’s son Joseph starting working at the store in 1926, and eventually took it over. In 1948, Joseph Wile, a lover of modern architecture, built a new, modern-style building in downtown. The Wolf-Wile building was later added to the National Register of Historical Places for its modern design. Joseph Wile kept the business open even after it became the last department store still located downtown. With the continuing decline of downtown, and not wanting to move to a mall, Wile decided to close the store and retire in 1992.

In 1935, Mary Wenneker rented a downtown building and then informed her surprised husband Al that they were going to open a shoe store. Two weeks Wenneker’s was open for business. After a few slow years, the store thrived, especially after the 1937 flood brought many people from Louisville and other affected towns to Lexington. The shoe store expanded over the years, and their sons James and William later joined the business. At its peak, the Wennekers had seven different stores in the area, including a second downtown location that sold special high fashion shoes. In the mid-1980s, the business closed as James and William focused on their real estate investments. James Wenneker became a major art collector, and later donated his prized collection to the University of Kentucky.

The Lexington Jewish community was growing during the early 20th century, reaching an estimated 750 people by 1927. At the time, most Lexington Jews were still in business. Several Jewish-owned stores established in the 19th century continued well into the 20th century. The Kaufman Clothing Company, which had been founded by Moses Kaufman in 1867, was bought by Phil Strauss in 1900. Strauss later brought his sons Robert and James into the business. After Robert died in 1953, James ran it by himself. When James retired in 1963, his son James W. Strauss took over the clothing store, and operated it well past its 100th anniversary. In 1910, Dolph Wile and Simon Wolf bought a 20-year-old department store and changed its name to the Wolf Wile Company. After Wolf died in 1921, the Wile family ran the business. Dolph’s son Joseph starting working at the store in 1926, and eventually took it over. In 1948, Joseph Wile, a lover of modern architecture, built a new, modern-style building in downtown. The Wolf-Wile building was later added to the National Register of Historical Places for its modern design. Joseph Wile kept the business open even after it became the last department store still located downtown. With the continuing decline of downtown, and not wanting to move to a mall, Wile decided to close the store and retire in 1992.

In 1935, Mary Wenneker rented a downtown building and then informed her surprised husband Al that they were going to open a shoe store. Two weeks Wenneker’s was open for business. After a few slow years, the store thrived, especially after the 1937 flood brought many people from Louisville and other affected towns to Lexington. The shoe store expanded over the years, and their sons James and William later joined the business. At its peak, the Wennekers had seven different stores in the area, including a second downtown location that sold special high fashion shoes. In the mid-1980s, the business closed as James and William focused on their real estate investments. James Wenneker became a major art collector, and later donated his prized collection to the University of Kentucky.

The Wolf Wile Building, constructed in 1948

The Wolf Wile Building, constructed in 1948

Lexington Jews were not just involved in retail stores. Polish-native Morris Baker moved to Lexington in 1921 and opened a junk business. Later known as Baker Iron & Metal, the business was eventually taken over by his son Harold. By 1997, Ben Baker, the third generation of the family, was running the business. The family sold the company in 2003. David Ades left Lithuania in 1913 and came to Lexington where his brother lived. After starting out as a peddler, Ades opened a wholesale dry goods business in 1919. His business grew and in 1925 was able to buy the Lexington Dry Goods Company. The newly renamed Ades-Lexington Dry Goods Company built a big warehouse in downtown Lexington and grew into a large wholesale operation. In addition to being a successful business owner, David Ades was also an important civic leader in Lexington. He led a $1 million fundraising campaign for St. Joseph Hospital and served as a director of the First Security National Bank. He was also on the board of the Julius Marks Sanatorium, which had been renamed after a $125,000 gift from Leo Marks in honor of his father. Ades belonged to both of Lexington’s Jewish congregations. When he died, the Lexington Herald wrote that his “was a career marked by many unpublicized instances of…helping people bring their families from Europe, of ‘bailing out’ flagging charity drives, and other good works.” His son Louis later joined the business, running it for seven years after David died in 1965. By the early 1970s, the rise of large chain stores hurt many of the small businesses the wholesale firm had sold to. With his customer base shrinking, Louis Ades decided to close the business.

Adath Israel's sanctuary

Adath Israel's sanctuary

Post World War II

After World War II, a growing number of Jewish families moved to Lexington. IBM built a manufacturing plant in the 1950s, which drew Jewish executives and engineers, and the University of Kentucky attracted a growing number of Jewish faculty members. The city’s Jewish population grew from 660 people in 1937 to 1,200 by 1960. Adath Israel’s membership doubled during the same period, reaching 200 families by 1962. Many of these newcomers were raised Orthodox, but wished to join the Reform congregation. This helped to lead Adath Israel away from classical Reform practice in the post-war years. In the 1950s, the temple board voted to allow worshipers to wear head coverings if they wanted. The bar mitzvah ritual was brought back around the same time. In 1960, the bat mitzvah for girls was introduced, as the congregation incorporated the study of Hebrew language into their religious school curriculum. The congregation also made an effort to reach out to members in nearby towns like Frankfort and Danville. For a while, the congregation held additional religious school classes in Frankfort, while Jane Sherago would drive to Danville each week to teach the eight Jewish children there.

Adath Israel struggled to keep up with the growth from new members and the baby boom. In 1950, the congregation added a new religious school wing. Just five years later, they added another new education wing to handle the growing religious school which had tripled in size during the decade after World War II. In the 1950s, the congregation began to discuss moving to a new synagogue, anticipating continued growth. Dot Levy donated $75,000 that was used to purchase 30 acres on Mount Tabor Road, and the congregation began to raise money for a new temple. Yet there was opposition to moving that far away and the congregation debated whether to move or expand their existing building. They ultimately decided to remain in their old building, and eventually enlarged and redesigned it in 1984.

Adath Israel continued to have a series of short-tenured rabbis until they hired William Leffler in 1964, who led the congregation for the next 22 years. Rabbi Leffler was replaced by Jonathan Adland in 1986. Rabbi Adland led Adath Israel until 2003. The congregation continued to grow under the tenures of Rabbis Leffler and Adland, reaching 340 families by 1995.

After World War II, a growing number of Jewish families moved to Lexington. IBM built a manufacturing plant in the 1950s, which drew Jewish executives and engineers, and the University of Kentucky attracted a growing number of Jewish faculty members. The city’s Jewish population grew from 660 people in 1937 to 1,200 by 1960. Adath Israel’s membership doubled during the same period, reaching 200 families by 1962. Many of these newcomers were raised Orthodox, but wished to join the Reform congregation. This helped to lead Adath Israel away from classical Reform practice in the post-war years. In the 1950s, the temple board voted to allow worshipers to wear head coverings if they wanted. The bar mitzvah ritual was brought back around the same time. In 1960, the bat mitzvah for girls was introduced, as the congregation incorporated the study of Hebrew language into their religious school curriculum. The congregation also made an effort to reach out to members in nearby towns like Frankfort and Danville. For a while, the congregation held additional religious school classes in Frankfort, while Jane Sherago would drive to Danville each week to teach the eight Jewish children there.

Adath Israel struggled to keep up with the growth from new members and the baby boom. In 1950, the congregation added a new religious school wing. Just five years later, they added another new education wing to handle the growing religious school which had tripled in size during the decade after World War II. In the 1950s, the congregation began to discuss moving to a new synagogue, anticipating continued growth. Dot Levy donated $75,000 that was used to purchase 30 acres on Mount Tabor Road, and the congregation began to raise money for a new temple. Yet there was opposition to moving that far away and the congregation debated whether to move or expand their existing building. They ultimately decided to remain in their old building, and eventually enlarged and redesigned it in 1984.

Adath Israel continued to have a series of short-tenured rabbis until they hired William Leffler in 1964, who led the congregation for the next 22 years. Rabbi Leffler was replaced by Jonathan Adland in 1986. Rabbi Adland led Adath Israel until 2003. The congregation continued to grow under the tenures of Rabbis Leffler and Adland, reaching 340 families by 1995.

Ohavey Zion's new synagogue, completed in 1987

Ohavey Zion's new synagogue, completed in 1987

Ohavay Zion had outgrown its small synagogue by 1940. The following year, they remodeled their building, adding a new social hall and kitchen. In 1964, the growing congregation added a building which housed a newly formed nursery school in addition to the religious school. After a series of short-term rabbis, Ohavay Zion hired Rabbi Bernard Schwab in 1962; he became the congregation’s first rabbi to stay longer than five years. Schwab was an Orthodox rabbi, though most of the members were more Conservative in orientation. By 1971, Ohavay Zion had 140 families and still held daily minyans.

Lexington Havurah

By the late 1970s, there was growing turmoil within Ohavay Zion over the issue of equal rights for women. Rabbi Schwab refused to give Torah honors to women or count them towards a minyan. In response, a number of families broke away to form the Lexington Havurah in 1978. Designed to be a smaller, more interactive group, the havurah soon joined the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism, though it never hired a rabbi or acquired a building. Most havurah members with children maintained their membership at Ohavey Zion or Adath Israel so they could attend religious school. In 1983, Ohavey Zion officially joined the Conservative movement. Soon after Rabbi Schwab’s death in 1985, Ohavey Zion voted to give women equal status within the congregation. Their new rabbi, Uri Smith, who had been raised Orthodox but had been ordained by the Reform Hebrew Union College, helped to oversee these changes. Even after women were given equal rights, the Lexington Havurah continued as members preferred the smaller, close-knit feel of the group to a formal congregation. In 1987, the havurah, which had 30 families, acquired a Torah that they used for their lay-led services held every three weeks. The group remains active.

Lexington Havurah

By the late 1970s, there was growing turmoil within Ohavay Zion over the issue of equal rights for women. Rabbi Schwab refused to give Torah honors to women or count them towards a minyan. In response, a number of families broke away to form the Lexington Havurah in 1978. Designed to be a smaller, more interactive group, the havurah soon joined the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism, though it never hired a rabbi or acquired a building. Most havurah members with children maintained their membership at Ohavey Zion or Adath Israel so they could attend religious school. In 1983, Ohavey Zion officially joined the Conservative movement. Soon after Rabbi Schwab’s death in 1985, Ohavey Zion voted to give women equal status within the congregation. Their new rabbi, Uri Smith, who had been raised Orthodox but had been ordained by the Reform Hebrew Union College, helped to oversee these changes. Even after women were given equal rights, the Lexington Havurah continued as members preferred the smaller, close-knit feel of the group to a formal congregation. In 1987, the havurah, which had 30 families, acquired a Torah that they used for their lay-led services held every three weeks. The group remains active.

Eli Capilouto, president of the

University of Kentucky

Eli Capilouto, president of the

University of Kentucky

The Late 20th Century

In the midst of the Lexington Jewish community’s steady growth in the 1970s, there was a serious discussion about consolidation. In the mid-70s, the leadership of Adath Israel and Ohavey Zion began to discuss a possible merger of the two congregations. Both congregations needed new buildings at the time, and they wanted their religious school children to mix with each other. The idea was to build a new joint synagogue on the 30-acre tract of land owned by Adath Israel. The new building would have two sanctuaries to accommodate two different services, and two kitchens. Each congregation would maintain their own rabbi, at least initially. A committee of board members from both congregations even drew up a constitution and bylaws and hired an architect to draw up plans for the joint synagogue. But after two years of discussions and negotiations, both congregations decided not to move forward with the merger. Since both congregations were continuing to grow, they no longer saw the need for consolidation.

In 1987, Ohavay Zion moved to a new building in the suburbs with a big Torah procession from their old synagogue. Their old building was sold and became an Italian restaurant, which is still open today. In 1988, the Conservative congregation hired Rabbi Eric Slaton, their second consecutive HUC-trained rabbi. Although Rabbi Slaton had previously served a Reform congregation in upstate New York, Ohavey Zion remained firmly Conservative. In 1998, they built an addition to the synagogue, with new larger classrooms, offices, and a multipurpose room. In 2000, Ohavey Zion hired Rabbi Sharon Cohen, its first spiritual leader to have graduated from the Jewish Theological Seminary.

In the 1960s, a group of Jewish women started Camp Shalom, a summer day camp. The camp was the seed that later grew into the Jewish Community Association, which worked to promote Jewish culture and identity and to foster cohesion within the Lexington Jewish community. The JCA eventually became the Jewish Federation of the Bluegrass, and took on leadership of the local United Jewish Appeal campaign. In 1971, there was still a B’nai B’rith chapter in Lexington with 140 members. There was also a Hadassah chapter, which had over 200 members. The Council of Jewish Women was still active at the time, serving the larger community. In the 1980s, there was discussion about the possibility of building a Jewish Community Center, but local leaders concluded that the community, with about 1500 Jews, was too small to sustain it.

In the midst of the Lexington Jewish community’s steady growth in the 1970s, there was a serious discussion about consolidation. In the mid-70s, the leadership of Adath Israel and Ohavey Zion began to discuss a possible merger of the two congregations. Both congregations needed new buildings at the time, and they wanted their religious school children to mix with each other. The idea was to build a new joint synagogue on the 30-acre tract of land owned by Adath Israel. The new building would have two sanctuaries to accommodate two different services, and two kitchens. Each congregation would maintain their own rabbi, at least initially. A committee of board members from both congregations even drew up a constitution and bylaws and hired an architect to draw up plans for the joint synagogue. But after two years of discussions and negotiations, both congregations decided not to move forward with the merger. Since both congregations were continuing to grow, they no longer saw the need for consolidation.

In 1987, Ohavay Zion moved to a new building in the suburbs with a big Torah procession from their old synagogue. Their old building was sold and became an Italian restaurant, which is still open today. In 1988, the Conservative congregation hired Rabbi Eric Slaton, their second consecutive HUC-trained rabbi. Although Rabbi Slaton had previously served a Reform congregation in upstate New York, Ohavey Zion remained firmly Conservative. In 1998, they built an addition to the synagogue, with new larger classrooms, offices, and a multipurpose room. In 2000, Ohavey Zion hired Rabbi Sharon Cohen, its first spiritual leader to have graduated from the Jewish Theological Seminary.

In the 1960s, a group of Jewish women started Camp Shalom, a summer day camp. The camp was the seed that later grew into the Jewish Community Association, which worked to promote Jewish culture and identity and to foster cohesion within the Lexington Jewish community. The JCA eventually became the Jewish Federation of the Bluegrass, and took on leadership of the local United Jewish Appeal campaign. In 1971, there was still a B’nai B’rith chapter in Lexington with 140 members. There was also a Hadassah chapter, which had over 200 members. The Council of Jewish Women was still active at the time, serving the larger community. In the 1980s, there was discussion about the possibility of building a Jewish Community Center, but local leaders concluded that the community, with about 1500 Jews, was too small to sustain it.

The Jewish Community in Lexington Today

The Lexington Jewish community has continued to grow over the last few decades. The University of Kentucky and its medical center has been a major draw for Jewish professionals. Jewish faculty were not new to the campus; Morris Sherago was head of the school’s Department of Bacteriology from 1924 into the 1940s. In recent years, Jews have held leading administrative positions within the university. In 2003, Michael Karpf became the head of the University of Kentucky Medical Center, and has worked to expand the facility. In 2010, Eli Capilouto became the first Jewish president of the University of Kentucky. In 2012, Mark Kornbluh was the school’s Dean of Arts & Sciences. Despite the strong presence of Jews in the administration, the Jewish student population at the university remains relatively low, with an estimated 300 students in 2012. There has been a Hillel at the university since after World War II. While it has never had a building, the Hillel does have a paid staff member. There is a small but thriving Jewish Studies program at UK. In addition to this influx of Jewish professionals and academics, a few Jewish-owned retail stores remain in Lexington. Barney Miller’s, an electronics store started by Bernard Miller in 1922, is still located downtown. The Joe Rosenberg Jewelry Store, opened by Joe Rosenberg in 1896, is still run by the family today.

In 2013, Lexington’s Jewish population, estimated at 2500 people, has never been larger. Both congregations have enjoyed slow yet steady growth in recent years, with Ohavay Zion having 211 households and Adath Israel having about 350. Lexington’s Jewish community has made the successful transition from a small community made up of retail merchants to a diverse community of professionals that will likely continue to thrive in the 21st century.

In 2013, Lexington’s Jewish population, estimated at 2500 people, has never been larger. Both congregations have enjoyed slow yet steady growth in recent years, with Ohavay Zion having 211 households and Adath Israel having about 350. Lexington’s Jewish community has made the successful transition from a small community made up of retail merchants to a diverse community of professionals that will likely continue to thrive in the 21st century.