Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Harlan / Middlesboro, Kentucky

Harlan / Middlesboro: Historical Overview

The Appalachian Mountains dominate southeastern Kentucky. The effort to remove the black rock buried in the mountains profoundly shaped the region, which became the home of several coal mining towns. With coal as its “cash crop,” southeastern Kentucky developed along with neighboring West Virginia in the late 19th century. A small number of Jews were drawn to these coal towns, not as miners, but as merchants catering to the growing population.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Harlan / Middlesboro

Middlesboro Boom, Bust, and Rebound

No city exemplified the idea of a coal “boomtown” more than Middlesboro, Kentucky. Seeing tremendous potential in the region, Scotsman Alexander Arthur organized a company that bought 100,000 acres in southeast Kentucky hoping to exploit its coal and timber. Needing a commercial and trading center for his project, he created Middlesboro in 1890, naming it after an industrial city in England. The town emerged almost overnight. In the year of its founding, it had 3,000 people, four banks, 16 hotels, five churches, a hospital, and even an opera house.

Fifteen Jewish families lived in Middlesboro by 1891, including brothers Sam and Herman Weinstein, who initially operated their dry goods store out of a tent. But with every boom comes a bust, and Middlesboro’s did not take long. When one of the English banks who had invested in Arthur’s enterprise failed, the speculative bubble burst, and the town went into default. The Panic of 1893 helped seal the town’s decline. The banks closed as did many of the town’s businesses. Much of the population left.

Despite this bust, many of Middlesboro’s Jews stayed, waiting for the town to rebound. By the turn of the century, Middlesboro was coming back as coal mining developed in the region. The Weinstein brothers, who had moved their business into a store in 1893, survived the bust, and later built a three-story building downtown to house their growing operation in 1906. Both Sam and Herman Weinstein became community leaders, working to improve the economic and social conditions of the town. Sam served on the city council. For many years, they were the largest taxpayers in the city, excluding the coal companies. Chain migration and kinship ties shaped this early Jewish community. Ida Euster, an immigrant from Roumania, and her eight children and their spouses all settled in Middlesboro or nearby Pineville between 1890 and 1920, opening retail stores in the coal mining towns. By 1910, about 100 Jews lived in this part of southeast Kentucky, mostly in Middlesboro. While most owned retail stores, William Horr owned a hotel while his wife Bertha ran a popular restaurant in Middlesboro. According to a local history of Middlesboro, in the 1910s and 1920s, “the Jewish merchants had such a large percentage of the mercantile houses that the town closed down for the Jewish high holidays.”

Organized Jewish Life in Middlesboro

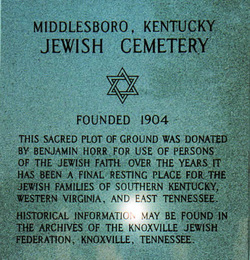

Middlesboro Jews first discussed the possibility of forming a congregation and building a synagogue in 1891, the height of the town’s boom. After the crash, these ambitions were put on hold. They would rely on visiting rabbis for important life cycle events. In 1897, Rabbi Isaac Winick of Knoxville, Tennessee’s Orthodox congregation came to Middlesboro to perform a circumcision and officiate at a wedding. The next effort to organize the Jewish community grew out of tragedy. When six-year-old Rebecca Ginsburg died in 1904, her grandfather, Ben Horr, donated land for a Jewish cemetery in Middlesboro. Horr stipulated that the cemetery plots must be given away for free. The following year, Jews in Middlesboro established a congregation. Without any surviving records, not much is known about the group. One source claimed that it was called Temple of Zion. Since they never had a synagogue, the congregation was never listed in the local city directory. The congregation met in Middlesboro’s Masonic Temple as Sam Weinstein would usually lead the Orthodox services. The group would periodically contact Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati about bringing in a student rabbi for the High Holidays in the 1910s and 1920s, although it usually didn’t work out since they wanted a traditional Orthodox service. The Reform seminary informed them that its students did not chant the Hebrew and used the Union Prayer Book. One year in the 1920s, HUC sent a student rabbi who had been raised Orthodox and was able to chant the Hebrew service. These High Holiday services would bring in Jews from the various other towns in southeast Kentucky; they often stayed at William Horr’s hotel. By the 1920s, the Jewish community of Middlesboro was shrinking and the congregation had become inactive by the end of the decade.

No city exemplified the idea of a coal “boomtown” more than Middlesboro, Kentucky. Seeing tremendous potential in the region, Scotsman Alexander Arthur organized a company that bought 100,000 acres in southeast Kentucky hoping to exploit its coal and timber. Needing a commercial and trading center for his project, he created Middlesboro in 1890, naming it after an industrial city in England. The town emerged almost overnight. In the year of its founding, it had 3,000 people, four banks, 16 hotels, five churches, a hospital, and even an opera house.

Fifteen Jewish families lived in Middlesboro by 1891, including brothers Sam and Herman Weinstein, who initially operated their dry goods store out of a tent. But with every boom comes a bust, and Middlesboro’s did not take long. When one of the English banks who had invested in Arthur’s enterprise failed, the speculative bubble burst, and the town went into default. The Panic of 1893 helped seal the town’s decline. The banks closed as did many of the town’s businesses. Much of the population left.

Despite this bust, many of Middlesboro’s Jews stayed, waiting for the town to rebound. By the turn of the century, Middlesboro was coming back as coal mining developed in the region. The Weinstein brothers, who had moved their business into a store in 1893, survived the bust, and later built a three-story building downtown to house their growing operation in 1906. Both Sam and Herman Weinstein became community leaders, working to improve the economic and social conditions of the town. Sam served on the city council. For many years, they were the largest taxpayers in the city, excluding the coal companies. Chain migration and kinship ties shaped this early Jewish community. Ida Euster, an immigrant from Roumania, and her eight children and their spouses all settled in Middlesboro or nearby Pineville between 1890 and 1920, opening retail stores in the coal mining towns. By 1910, about 100 Jews lived in this part of southeast Kentucky, mostly in Middlesboro. While most owned retail stores, William Horr owned a hotel while his wife Bertha ran a popular restaurant in Middlesboro. According to a local history of Middlesboro, in the 1910s and 1920s, “the Jewish merchants had such a large percentage of the mercantile houses that the town closed down for the Jewish high holidays.”

Organized Jewish Life in Middlesboro

Middlesboro Jews first discussed the possibility of forming a congregation and building a synagogue in 1891, the height of the town’s boom. After the crash, these ambitions were put on hold. They would rely on visiting rabbis for important life cycle events. In 1897, Rabbi Isaac Winick of Knoxville, Tennessee’s Orthodox congregation came to Middlesboro to perform a circumcision and officiate at a wedding. The next effort to organize the Jewish community grew out of tragedy. When six-year-old Rebecca Ginsburg died in 1904, her grandfather, Ben Horr, donated land for a Jewish cemetery in Middlesboro. Horr stipulated that the cemetery plots must be given away for free. The following year, Jews in Middlesboro established a congregation. Without any surviving records, not much is known about the group. One source claimed that it was called Temple of Zion. Since they never had a synagogue, the congregation was never listed in the local city directory. The congregation met in Middlesboro’s Masonic Temple as Sam Weinstein would usually lead the Orthodox services. The group would periodically contact Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati about bringing in a student rabbi for the High Holidays in the 1910s and 1920s, although it usually didn’t work out since they wanted a traditional Orthodox service. The Reform seminary informed them that its students did not chant the Hebrew and used the Union Prayer Book. One year in the 1920s, HUC sent a student rabbi who had been raised Orthodox and was able to chant the Hebrew service. These High Holiday services would bring in Jews from the various other towns in southeast Kentucky; they often stayed at William Horr’s hotel. By the 1920s, the Jewish community of Middlesboro was shrinking and the congregation had become inactive by the end of the decade.

The

Harlan County Courier

announced

The

Harlan County Courier

announced local Jews' observance for the high holidays

on its front page in 1931

Organized Jewish Life in Harlan

As Middlesboro declined, the center of Jewish life in the region was shifting eastward to Harlan. After the Louisville & Nashville railroad was built though Harlan in 1911, the tiny town grew to become a commercial center for the area’s coal mining industry. Its population increased from 557 people in 1910 to well over 4,000 in 1930. By 1920, three Jewish families lived in Harlan, all of whom were merchants and Russian immigrants. By the 1930s, about 60 Jews lived in Harlan County. Thus, it was not surprising that an effort to form a new congregation in the area was based in Harlan.

In 1930, a group of Jews gathered to discuss forming a new congregation, but the effort failed. One problem was the dispersed nature of the area’s Jewish population, who were scattered in different towns. In September, 1931, the group tried again, meeting at Sol Geller’s store in Cumberland, Kentucky. This time they were successful, establishing the B’nai Sholom congregation. According to its founding constitution, the purpose of the congregation was “to awaken, foster, encourage and promote among the Jews of S.E. Kentucky the study and practice of Judaism.” Harry Linden, a local doctor who was instrumental in the group’s formation, was elected B’nai Sholom’s first president. The congregation quickly organized High Holiday services. The Harlan County Courier noted that “the Jews of Harlan for the first time in the history of Harlan have made arrangements to conduct religious services for these Holy Days.” The group quickly acquired a Torah and held services in the Harlan Masonic Temple. They mailed a card to all of the Jews in a 40-mile radius inviting them to Harlan for the High Holidays. By October, 1931, B’nai Sholom had 27 members. With the exception of Dr. Linden, most all the members were merchants.

B’nai Sholom was a traditional congregation, celebrating Rosh Hashanah for two days and serving kosher food at official functions. Worshipers wore yarmulkes and tallit and used the traditional Adler prayer book. Yet the members worked with the Reform movement as the regional office of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations helped them to organize. In December, 1931, the UAHC held a regional meeting in Harlan. In 1932, Rabbi Milton Greenwald of the Reform temple in Knoxville spoke to the group in Pineville. It was very much of a regional congregation, with its membership divided between Harlan, Pineville, Middlesboro, and six other small towns in southeast Kentucky. In 1932, they held High Holiday services at the Masonic Temple in Middlesboro. During the rest of the year, they held Friday night services at the home of member Israel Roodene.

As Middlesboro declined, the center of Jewish life in the region was shifting eastward to Harlan. After the Louisville & Nashville railroad was built though Harlan in 1911, the tiny town grew to become a commercial center for the area’s coal mining industry. Its population increased from 557 people in 1910 to well over 4,000 in 1930. By 1920, three Jewish families lived in Harlan, all of whom were merchants and Russian immigrants. By the 1930s, about 60 Jews lived in Harlan County. Thus, it was not surprising that an effort to form a new congregation in the area was based in Harlan.

In 1930, a group of Jews gathered to discuss forming a new congregation, but the effort failed. One problem was the dispersed nature of the area’s Jewish population, who were scattered in different towns. In September, 1931, the group tried again, meeting at Sol Geller’s store in Cumberland, Kentucky. This time they were successful, establishing the B’nai Sholom congregation. According to its founding constitution, the purpose of the congregation was “to awaken, foster, encourage and promote among the Jews of S.E. Kentucky the study and practice of Judaism.” Harry Linden, a local doctor who was instrumental in the group’s formation, was elected B’nai Sholom’s first president. The congregation quickly organized High Holiday services. The Harlan County Courier noted that “the Jews of Harlan for the first time in the history of Harlan have made arrangements to conduct religious services for these Holy Days.” The group quickly acquired a Torah and held services in the Harlan Masonic Temple. They mailed a card to all of the Jews in a 40-mile radius inviting them to Harlan for the High Holidays. By October, 1931, B’nai Sholom had 27 members. With the exception of Dr. Linden, most all the members were merchants.

B’nai Sholom was a traditional congregation, celebrating Rosh Hashanah for two days and serving kosher food at official functions. Worshipers wore yarmulkes and tallit and used the traditional Adler prayer book. Yet the members worked with the Reform movement as the regional office of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations helped them to organize. In December, 1931, the UAHC held a regional meeting in Harlan. In 1932, Rabbi Milton Greenwald of the Reform temple in Knoxville spoke to the group in Pineville. It was very much of a regional congregation, with its membership divided between Harlan, Pineville, Middlesboro, and six other small towns in southeast Kentucky. In 1932, they held High Holiday services at the Masonic Temple in Middlesboro. During the rest of the year, they held Friday night services at the home of member Israel Roodene.

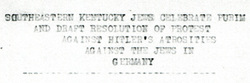

Announcement of B'nai Sholom's 1933 protest against Hitler

Announcement of B'nai Sholom's 1933 protest against Hitler

Although they were living in an isolated area with no direct rail connection to any eastern port cities, the members of B’nai Sholom were not provincial, but were connected to the larger Jewish world. In 1931, they held a Simchat Torah program that included Yiddish songs and speeches in addition to Dr. Linden’s address on “Jews as Contributors to Civilization and Science.” The event opened with the “Star Spangled Banner” and closed with “Hatikvah,” the Zionist anthem. The fact that the program included Yiddish indicates that a good number of the members were immigrants who best understood that language. Also, the inclusion of “Hatikvah” reflects a support for Zionism within the community. Indeed, there had earlier been a Daughters of Zion organization in the area, while a Hadassah chapter was formed in the 1930s.

In 1933, the congregation held a Purim event which drew over 100 people to Middlesboro. During the program, the congregation adopted a motion “protesting against the Haman-like designs of the German Hitler.” The congregation sent a copy of the resolution to President Roosevelt and the U.S. Ambassador to Germany. Local Christian ministers joined the protest statement. Even though Hitler had just recently come to power, southeastern Kentucky Jews were already aware of the threat he posed to Jews in Germany.

In 1933, the congregation held a Purim event which drew over 100 people to Middlesboro. During the program, the congregation adopted a motion “protesting against the Haman-like designs of the German Hitler.” The congregation sent a copy of the resolution to President Roosevelt and the U.S. Ambassador to Germany. Local Christian ministers joined the protest statement. Even though Hitler had just recently come to power, southeastern Kentucky Jews were already aware of the threat he posed to Jews in Germany.

Changes at B'nai Sholom

When Dr. Linden, who had been the congregation’s president since its founding, moved to Baltimore in 1933, B’nai Sholom lost much of its energy. While they still met for High Holiday services, most other activities ceased. In 1935, B’nai Sholom member Harry Miller wrote to Linden declaring that “we are trying to reorganize the B’nai Sholom congregation. It may not include Middlesboro for they want to have it the Reform way. But we will try the best we can to restore this congregation to about its former capacity.” Indeed, many Middlesboro members had dropped out of B’nai Sholom, holding their own separate High Holiday services in 1935 with a student rabbi from Hebrew Union College. While part of the reason for this split was the distance between Harlan and Middlesboro (40 miles over difficult terrain), as Miller indicated, disagreement over worship practices was the leading cause for this short-lived split. By the end of the 1930s, most Middlesboro Jews had rejoined B’nai Sholom, which once again became active. By 1940, B’nai Sholom had rented a second-story room in the old Harlan Masonic Hall, which they outfitted as a synagogue. The small sanctuary seated 60 people. By 1948, an estimated 160 Jews lived in southeastern Kentucky.

When Dr. Linden, who had been the congregation’s president since its founding, moved to Baltimore in 1933, B’nai Sholom lost much of its energy. While they still met for High Holiday services, most other activities ceased. In 1935, B’nai Sholom member Harry Miller wrote to Linden declaring that “we are trying to reorganize the B’nai Sholom congregation. It may not include Middlesboro for they want to have it the Reform way. But we will try the best we can to restore this congregation to about its former capacity.” Indeed, many Middlesboro members had dropped out of B’nai Sholom, holding their own separate High Holiday services in 1935 with a student rabbi from Hebrew Union College. While part of the reason for this split was the distance between Harlan and Middlesboro (40 miles over difficult terrain), as Miller indicated, disagreement over worship practices was the leading cause for this short-lived split. By the end of the 1930s, most Middlesboro Jews had rejoined B’nai Sholom, which once again became active. By 1940, B’nai Sholom had rented a second-story room in the old Harlan Masonic Hall, which they outfitted as a synagogue. The small sanctuary seated 60 people. By 1948, an estimated 160 Jews lived in southeastern Kentucky.

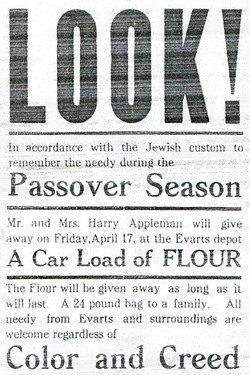

The Applemans took out this

newspaper ad

The Applemans took out this

newspaper ad to announce their effort to feed local miners in 1931.

20th Century Regional Politics

Most Jews in the region continued to concentrate in retail trade, though the turmoil of the coal industry could make it difficult to thrive. Long strikes between miners and the coal companies would hurt Jewish businesses and by extension the congregation. As these labor struggles became increasingly virulent, Jews were sometimes caught in the middle. Polish immigrants Harry and Bina Appleman opened a general store by 1920 in Evarts, Kentucky. After many local miners were fired for joining a union in 1931, the Applemans decided to help their families. They would feed 40 to 50 children each day during the standoff. During Passover, the Applemans ran an ad in the local newspaper stating that they would give away a railroad car full of flour to anyone in need “regardless of color and creed.” Each needy family would be given a 24-pound bag of flour. This donation was a significant expense for the Applemans, who had scrimped and saved the money which they now decided to use to help the needy miners. The Black Mountain Coal Corporation did not appreciate the Appleman’s largesse, and swore out a criminal complaint against the couple for criminal syndicalism. Although the charges were eventually dropped, the Applemans were targeted by company thugs, who shot into their home. Because of these threats, the Applemans left Evarts, moving to Brooklyn.

Other Jews successfully negotiated the bitter politics of the region, serving in local office, although sometimes not without controversy. Ike Ginsburg left Lithuania in 1887 and lived in Middlesboro by 1896. Later, he opened a dry goods store in town. Middlesboro was a wild frontier town, with lots of illegal gambling and drinking. Ginsburg seemed to be friendly with the owners of these establishments. Ginsburg’s cousin, Jack Zuta, who came to Middlesboro each year for the High Holidays, was a member of Bugsy Moran’s gang in Chicago. When Zuta was gunned down in 1930 in the Windy City, his body was brought back to Middlesboro and buried in the Jewish cemetery. Despite his questionable associations, Ginsburg was elected mayor of Middlesboro in the 1930s. A local grand jury accused Ginsburg of openly allowing saloons, casinos, and brothels to operate in the city. Facing charges of corruption, Ginsburg’s tenure as mayor was limited to one term. Amidst this controversy, Ginsburg’s religion never became a public issue. Indeed, several other Jews served in local office in the area. Emil Hilburn served as mayor of Middlesboro in 1912. Abe Euster was elected mayor of Pineville in the 1960s, while Irvin Gergely served as a city councilman in Harlan.

Most Jews in the region continued to concentrate in retail trade, though the turmoil of the coal industry could make it difficult to thrive. Long strikes between miners and the coal companies would hurt Jewish businesses and by extension the congregation. As these labor struggles became increasingly virulent, Jews were sometimes caught in the middle. Polish immigrants Harry and Bina Appleman opened a general store by 1920 in Evarts, Kentucky. After many local miners were fired for joining a union in 1931, the Applemans decided to help their families. They would feed 40 to 50 children each day during the standoff. During Passover, the Applemans ran an ad in the local newspaper stating that they would give away a railroad car full of flour to anyone in need “regardless of color and creed.” Each needy family would be given a 24-pound bag of flour. This donation was a significant expense for the Applemans, who had scrimped and saved the money which they now decided to use to help the needy miners. The Black Mountain Coal Corporation did not appreciate the Appleman’s largesse, and swore out a criminal complaint against the couple for criminal syndicalism. Although the charges were eventually dropped, the Applemans were targeted by company thugs, who shot into their home. Because of these threats, the Applemans left Evarts, moving to Brooklyn.

Other Jews successfully negotiated the bitter politics of the region, serving in local office, although sometimes not without controversy. Ike Ginsburg left Lithuania in 1887 and lived in Middlesboro by 1896. Later, he opened a dry goods store in town. Middlesboro was a wild frontier town, with lots of illegal gambling and drinking. Ginsburg seemed to be friendly with the owners of these establishments. Ginsburg’s cousin, Jack Zuta, who came to Middlesboro each year for the High Holidays, was a member of Bugsy Moran’s gang in Chicago. When Zuta was gunned down in 1930 in the Windy City, his body was brought back to Middlesboro and buried in the Jewish cemetery. Despite his questionable associations, Ginsburg was elected mayor of Middlesboro in the 1930s. A local grand jury accused Ginsburg of openly allowing saloons, casinos, and brothels to operate in the city. Facing charges of corruption, Ginsburg’s tenure as mayor was limited to one term. Amidst this controversy, Ginsburg’s religion never became a public issue. Indeed, several other Jews served in local office in the area. Emil Hilburn served as mayor of Middlesboro in 1912. Abe Euster was elected mayor of Pineville in the 1960s, while Irvin Gergely served as a city councilman in Harlan.

Photo courtesy of Melvin Sturm

Photo courtesy of Melvin Sturm

The Decline of B'nai Sholom

By the 1950s, B’nai Sholom struggled to remain active, though they were able to bring in student rabbis for the High Holidays. One problem was the dispersed nature of the congregation, which made it hard to hold regular services. One student rabbi wrote in 1955, “two-thirds of [members] live 30-40 miles away from the synagogue.” Although these student rabbis came from the Reform seminary, Hebrew Union College, the congregation was essentially Conservative and still used the traditional Adler prayer book. Several members of the congregation kept kosher. The student rabbis during the 1950s noted that the Harlan congregation was shrinking. B’nai Sholom had 30 members in 1950, but this figure dropped as the coal industry declined. By 1955, there were only 15 dues paying members of the congregation. Their student rabbi in 1959 reported that “due to the decline in coal mining…business conditions are poor. As a result, there is a decrease in the number of congregants.” By 1957, the congregation no longer had a religious school and by the end of the decade they were struggling to pay their expenses, including the rent on their synagogue. In 1962, they reached a new low in membership and were unable to afford a student rabbi for the High Holidays.

The congregation enjoyed a slight resurgence in the mid-1960s, growing to 16 families by 1965, though there were tensions between the old-timers and newer families. Three elderly men, Israel Roodene, William Ullman, and William Coplowitz, took turns chanting the Hebrew prayers during services, while many in the audience wanted a Reform service with more English. One student rabbi reported that “these three men take turns chanting the prayers in Hebrew to the extreme boredom of the congregation with hardly a respite for English.” The rabbi blamed this situation for the lack of interest in holding regular Shabbat services. Yet despite these complaints, it was these old-timers who were the most committed to keeping the congregation going; they were still the primary energy within B’nai Sholom.

When these three leaders all died within a year of each other in the early 1970s, the congregation began to discuss disbanding. In 1972, B’nai Sholom had only ten families, but was still able to bring in an HUC student for the High Holidays. Yet that student rabbi reported that the members of B’nai Sholom had decided to dissolve the congregation by the end of the year “because of the death of three elderly men who were the backbone of the congregation.” Without these key leaders and with membership continuing to decline, the congregation decided that organized Jewish life in southeastern Kentucky was no longer viable.

By the 1950s, B’nai Sholom struggled to remain active, though they were able to bring in student rabbis for the High Holidays. One problem was the dispersed nature of the congregation, which made it hard to hold regular services. One student rabbi wrote in 1955, “two-thirds of [members] live 30-40 miles away from the synagogue.” Although these student rabbis came from the Reform seminary, Hebrew Union College, the congregation was essentially Conservative and still used the traditional Adler prayer book. Several members of the congregation kept kosher. The student rabbis during the 1950s noted that the Harlan congregation was shrinking. B’nai Sholom had 30 members in 1950, but this figure dropped as the coal industry declined. By 1955, there were only 15 dues paying members of the congregation. Their student rabbi in 1959 reported that “due to the decline in coal mining…business conditions are poor. As a result, there is a decrease in the number of congregants.” By 1957, the congregation no longer had a religious school and by the end of the decade they were struggling to pay their expenses, including the rent on their synagogue. In 1962, they reached a new low in membership and were unable to afford a student rabbi for the High Holidays.

The congregation enjoyed a slight resurgence in the mid-1960s, growing to 16 families by 1965, though there were tensions between the old-timers and newer families. Three elderly men, Israel Roodene, William Ullman, and William Coplowitz, took turns chanting the Hebrew prayers during services, while many in the audience wanted a Reform service with more English. One student rabbi reported that “these three men take turns chanting the prayers in Hebrew to the extreme boredom of the congregation with hardly a respite for English.” The rabbi blamed this situation for the lack of interest in holding regular Shabbat services. Yet despite these complaints, it was these old-timers who were the most committed to keeping the congregation going; they were still the primary energy within B’nai Sholom.

When these three leaders all died within a year of each other in the early 1970s, the congregation began to discuss disbanding. In 1972, B’nai Sholom had only ten families, but was still able to bring in an HUC student for the High Holidays. Yet that student rabbi reported that the members of B’nai Sholom had decided to dissolve the congregation by the end of the year “because of the death of three elderly men who were the backbone of the congregation.” Without these key leaders and with membership continuing to decline, the congregation decided that organized Jewish life in southeastern Kentucky was no longer viable.

The Jewish Community in Harlan / Middlesboro Today

Although there was no longer a congregation, a handful of Jews remained in the area. The Euster family continued to own the Fair Store in Middlesboro into the 1970s, while Jack Friedman owned Royal Jewelers. In recent years, a few doctors have moved to the area, with some joining congregations in Knoxville, Tennessee, but most do not stay very long. Today, few if any Jews live in southeastern Kentucky.

In 1968, the remaining Jews of the area decided to create an endowment to pay for the perpetual care of the Middlesboro cemetery. They contacted people who had relatives buried there, and raised $18,000. After B’nai Sholom closed in 1972, its yahrzeit plaque was moved to the cemetery, where it was mounted in a specially built brick wall. There is still a group of former residents who administer the trust fund and maintain the cemetery. Since 1984, brothers Melvin and Evan Sturm have led this effort. Today, the Jewish cemetery in Middlesboro, located on Hebrew Road, is the last remaining vestige of Jewish life in southeastern Kentucky.

In 1968, the remaining Jews of the area decided to create an endowment to pay for the perpetual care of the Middlesboro cemetery. They contacted people who had relatives buried there, and raised $18,000. After B’nai Sholom closed in 1972, its yahrzeit plaque was moved to the cemetery, where it was mounted in a specially built brick wall. There is still a group of former residents who administer the trust fund and maintain the cemetery. Since 1984, brothers Melvin and Evan Sturm have led this effort. Today, the Jewish cemetery in Middlesboro, located on Hebrew Road, is the last remaining vestige of Jewish life in southeastern Kentucky.