Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Paducah, Kentucky

Historical Overview

|

Located at the confluence of the Ohio and Tennessee Rivers, and not far from the Mississippi, Paducah seemed ideally situated to serve as a trading gateway to the South. Initially, the town was overshadowed by neighboring Smithland, which was elevated on bluffs and had a deep natural harbor. By 1850, Paducah, which was flat and had drainage problems, was the smaller town, as most of the area’s wealthy planters and businessmen lived in Smithland. The coming of the railroad in the 1850s changed this. After the Civil War, Paducah became the midway stop between Louisville and Memphis on the railroad and emerged as a major river port. By the late 19th century, Paducah was a wholesaling and commercial center for the region. There has been a Jewish presence in Paducah since the 1840s.

|

Stories of the Jewish Community in Paducah

Mangold Livingston

Mangold Livingston

Early Settlers

The earliest Jews in Paducah arrived in the 1840s, and included Morris and Abraham Uri, D. Lowenstein, and Leopold Klaw, each of whom opened small merchandise stores on Front Street. After the railroad was built in Paducah in the 1850s, a growing number of Jewish immigrants settled in the town. A handful of Jews who had been living in Smithland, including Benjamin Weille, Samuel Dreyfus, and Mangold Livingston, came to Paducah by the end of the Civil War.

By 1859, there were 11 Jewish-owned businesses in Paducah, several of which were partnerships of two or more Jews. Many ran clothing stores; of the eight clothing businesses in Paducah in 1859, six were Jewish-owned. One of these included a store owned by Solomon Greenbaum and Cesar Kaskel. Kaskel, a native of Prussia, had moved to Paducah in 1858. In 1859, 20 Paducah Jews founded the Chevra Yeshurun burial society and bought land for a cemetery.

The earliest Jews in Paducah arrived in the 1840s, and included Morris and Abraham Uri, D. Lowenstein, and Leopold Klaw, each of whom opened small merchandise stores on Front Street. After the railroad was built in Paducah in the 1850s, a growing number of Jewish immigrants settled in the town. A handful of Jews who had been living in Smithland, including Benjamin Weille, Samuel Dreyfus, and Mangold Livingston, came to Paducah by the end of the Civil War.

By 1859, there were 11 Jewish-owned businesses in Paducah, several of which were partnerships of two or more Jews. Many ran clothing stores; of the eight clothing businesses in Paducah in 1859, six were Jewish-owned. One of these included a store owned by Solomon Greenbaum and Cesar Kaskel. Kaskel, a native of Prussia, had moved to Paducah in 1858. In 1859, 20 Paducah Jews founded the Chevra Yeshurun burial society and bought land for a cemetery.

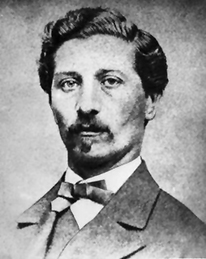

Cesar Kaskel.

Cesar Kaskel. Photo courtesy of the Jacob Rader Marcus

Center of the American Jewish Archives.

The Civil War

Paducah was quickly occupied by the Union Army during the Civil War, because of its strategic location. Paducah businessmen were forbidden from trading with Confederate territories, an order most Jewish merchants abided by. Some probably did take part in the smuggling and illegal trading that was rampant in the area during the war. Although many soldiers also participated in the illegal trade, Jews came to be blamed for it. On December 17, 1862, Union General Ulysses S. Grant issued his infamous Orders No. 11, expelling all Jews from the entire territory under his command. Paducah was one of the few places where Grant’s order was enforced since the general’s camp in Holly Springs, Mississippi, was soon cut off by Confederate forces, and communication with other parts of the territory was suspended.

On December 28th, the local provost marshal in Paducah called for Cesar Kaskel and informed him that he would have to leave the city within 24 hours. Kaskel, who supported the North and was vice-president of the Paducah Union League Club, was shocked by the order. Together with the brothers Daniel, Marcus, and Alexander Wolff, Kaskel quickly sent a telegram of protest to President Lincoln calling on him to overturn this “inhuman order” that violated Jews’ rights under the constitution.When Kaskel did not receive an immediate response, he left at once for Washington, D.C. to lobby the government directly. In the meantime, about 30 Jewish families lived in Paducah, and most left the city, traveling up the Ohio River to Cincinnati. Kaskel arrived in the nation’s capital on January 3, 1863, and with the help of an Ohio congressman, got in to meet with President Lincoln, who had not heard of Grant’s order. After hearing Kaskel’s explanation of the situation, the president quickly agreed to overturn the order. On January 6th, General Grant’s office sent out notice that the order was revoked. Most of the expelled Paducah Jews returned to the city. Grant’s Order was only enforced for a little over a week.

Paducah was quickly occupied by the Union Army during the Civil War, because of its strategic location. Paducah businessmen were forbidden from trading with Confederate territories, an order most Jewish merchants abided by. Some probably did take part in the smuggling and illegal trading that was rampant in the area during the war. Although many soldiers also participated in the illegal trade, Jews came to be blamed for it. On December 17, 1862, Union General Ulysses S. Grant issued his infamous Orders No. 11, expelling all Jews from the entire territory under his command. Paducah was one of the few places where Grant’s order was enforced since the general’s camp in Holly Springs, Mississippi, was soon cut off by Confederate forces, and communication with other parts of the territory was suspended.

On December 28th, the local provost marshal in Paducah called for Cesar Kaskel and informed him that he would have to leave the city within 24 hours. Kaskel, who supported the North and was vice-president of the Paducah Union League Club, was shocked by the order. Together with the brothers Daniel, Marcus, and Alexander Wolff, Kaskel quickly sent a telegram of protest to President Lincoln calling on him to overturn this “inhuman order” that violated Jews’ rights under the constitution.When Kaskel did not receive an immediate response, he left at once for Washington, D.C. to lobby the government directly. In the meantime, about 30 Jewish families lived in Paducah, and most left the city, traveling up the Ohio River to Cincinnati. Kaskel arrived in the nation’s capital on January 3, 1863, and with the help of an Ohio congressman, got in to meet with President Lincoln, who had not heard of Grant’s order. After hearing Kaskel’s explanation of the situation, the president quickly agreed to overturn the order. On January 6th, General Grant’s office sent out notice that the order was revoked. Most of the expelled Paducah Jews returned to the city. Grant’s Order was only enforced for a little over a week.

Meyer Weil

Meyer Weil

In addition to this brief expulsion, wartime hardships and regulations also interrupted the trade of Jewish merchants in Paducah. When the Confederate army attacked Paducah in 1863, many businesses closed, with their owners transporting their merchandise to safer cities. These wartime privations caused many Paducah Jews to leave. Kaskel moved to New York City while the Wolff brothers went back to Germany after the war. Of the 20 Jewish men living in Paducah in 1859, only eight still lived in the city in 1870. Despite this fact, Paducah Jews did not feel unwelcome. They blamed the Union army, not their Gentile neighbors, for the expulsion. There is even a legend among Paducah Jews that local residents helped to hide Jews during the expulsion. Whether or not these stories are true, they stemmed from the fact that Jews were well accepted in Paducah, both before and after the war. They were important civic and business leaders who helped guide the city’s development in the decades after the war. Most notably, Meyer Weil who came to Paducah in 1863 and later opened a wholesale tobacco firm, was elected to four terms as mayor in the 1870s. During his tenure, he built a city hospital and led Paducah through the Panic of 1873, helping to restore the city’s credit rating. Later, Weil served as the city tax collector and spent two terms representing Paducah in the state legislature. Weil’s career shows that Jews found opportunity and acceptance in Paducah soon after the expulsion.

Bene Yeshurun's first synagogue

Bene Yeshurun's first synagogue

Organized Jewish Life in Paducah

The Civil War also disrupted the spiritual lives of Paducah Jews. Although they had founded a burial society in 1859, the group remained inactive during the early years of the war. It wasn’t officially chartered until 1864. Not until 1868 did they begin to hold services, meeting for the High Holidays on the 3rd floor of Mangold Livingston’s dry goods store. They brought in a traveling reader to lead the services and auctioned off seats to pay his expenses. Paducah Jews met in the same place for the High Holidays in 1869 and 1870, though there is no evidence that they met for Shabbat services during the rest of the year. A B’nai B’rith lodge was established in 1870 with 27 charter members; 17 of these founding members were under the age of 40, reflecting the relative youth of the Paducah Jewish community. The founding of the lodge helped inspire Paducah Jews to establish a formal congregation. Soon after, two committees, one of men and the other of women, worked together to raise money to buy land and build a synagogue. In 1871, the Chevra Yeshurun Burial Society amended its state charter to include the new purpose of forming a congregation for religious worship. They named this congregation Kehillah Kodesh Bene Yeshurun (Holy Community of the People of Righteousness).

With Meyer Lieber as its first president, Bene Yeshurun soon bought land on Chestnut Street and constructed a modest two-story frame building. In September, 1871, the congregation dedicated this new synagogue in a ceremony featuring a Torah procession that started at Lieber’s house. Mayor J.W. Sauner, the city council, and many other local Gentiles took part in the procession. The dedication attracted several locals who were curious to see a Jewish house of worship and knew little about Judaism. Bene Yeshurun hired Leon Leopold as its first spiritual leader in 1871. In addition to leading services, Leopold also taught the congregation’s Sunday school.

The Civil War also disrupted the spiritual lives of Paducah Jews. Although they had founded a burial society in 1859, the group remained inactive during the early years of the war. It wasn’t officially chartered until 1864. Not until 1868 did they begin to hold services, meeting for the High Holidays on the 3rd floor of Mangold Livingston’s dry goods store. They brought in a traveling reader to lead the services and auctioned off seats to pay his expenses. Paducah Jews met in the same place for the High Holidays in 1869 and 1870, though there is no evidence that they met for Shabbat services during the rest of the year. A B’nai B’rith lodge was established in 1870 with 27 charter members; 17 of these founding members were under the age of 40, reflecting the relative youth of the Paducah Jewish community. The founding of the lodge helped inspire Paducah Jews to establish a formal congregation. Soon after, two committees, one of men and the other of women, worked together to raise money to buy land and build a synagogue. In 1871, the Chevra Yeshurun Burial Society amended its state charter to include the new purpose of forming a congregation for religious worship. They named this congregation Kehillah Kodesh Bene Yeshurun (Holy Community of the People of Righteousness).

With Meyer Lieber as its first president, Bene Yeshurun soon bought land on Chestnut Street and constructed a modest two-story frame building. In September, 1871, the congregation dedicated this new synagogue in a ceremony featuring a Torah procession that started at Lieber’s house. Mayor J.W. Sauner, the city council, and many other local Gentiles took part in the procession. The dedication attracted several locals who were curious to see a Jewish house of worship and knew little about Judaism. Bene Yeshurun hired Leon Leopold as its first spiritual leader in 1871. In addition to leading services, Leopold also taught the congregation’s Sunday school.

Herbert Wallerstein

Herbert Wallerstein

When the congregation was formed, there were many heated discussions about religious practices and rituals. Most members wanted Reform services, but a traditional faction pushed for separate seating for men and women and the requirement that men wear head coverings. The group finally agreed to have mixed gender seating, while Morris Uri worked out a compromise in which members could wear yarmulkes during services if they liked. In the end, only one member wore a yarmulke at the congregation’s services. When the synagogue was dedicated in 1871, it included an organ and the congregation had a mixed-gender choir, reflecting the Reform nature of its services. In 1872, Bene Yeshurun held it first confirmation ceremony with six children getting confirmed that year. According to member Isaac Bernheim, after the successful confirmation ceremony, “the battle for Reform Judaism had been won and the question of Orthodox ceremonials, which heretofore had created discussion and trouble, was forever put to rest.” The congregation joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations by 1880.

This Friedman-Keiler mausoleum

This Friedman-Keiler mausoleum reflects the family's economic prominence.

A Growing Community

After the Civil War, the Jewish community grew quickly as Paducah flourished economically. By 1866, 34 Jewish men were listed in the city directory. Their ranks included skilled craftsmen like shoemakers, tailors, and bakers in addition to merchants. Because of Paducah’s location at the junction of the Ohio River and major railroads, several Jews opened wholesale operations, selling dry goods, groceries, tobacco, and whiskey to stores around the region. As Southerners clamored for goods after the war, Paducah merchants thrived. A growing number of Jewish immigrants from Europe came to Paducah in the years after the Civil War. By 1878, an estimated 200 Jews lived in Paducah. Several of them established businesses that remained in operation for over a century.

Paducah Jews dominated the local whiskey business. Five of the six wholesale liquor firms in Paducah in 1894 were Jewish-owned. Many of these companies eventually moved into distilling. Some of their owners were among the most prominent and respected businessmen in town. Joseph Friedman started a distillery and wholesale whiskey business with his brother-in-law John Keiler in 1890. Their distillery became one of the largest in the country, producing 20,000 barrels of whiskey a year. Friedman also built and operated the Palmer Hotel and the Kentucky Theater. As president of the Commercial Club, Friedman worked to recruit industry to Paducah. He became a leading local philanthropist, creating a settlement house to help the city’s poor. When Friedman died in 1913, hundreds of vehicles took part in a procession that stretched over three miles long. After Friedman’s death, the Keiler family continued to run the business, and became major Paducah philanthropists as well. In 1923, John Keiler donated $5000 to help build a stadium behind the local high school, which was named Keiler Field. In 1930, the family donated land to the city for a park, which was named in their honor

After the Civil War, the Jewish community grew quickly as Paducah flourished economically. By 1866, 34 Jewish men were listed in the city directory. Their ranks included skilled craftsmen like shoemakers, tailors, and bakers in addition to merchants. Because of Paducah’s location at the junction of the Ohio River and major railroads, several Jews opened wholesale operations, selling dry goods, groceries, tobacco, and whiskey to stores around the region. As Southerners clamored for goods after the war, Paducah merchants thrived. A growing number of Jewish immigrants from Europe came to Paducah in the years after the Civil War. By 1878, an estimated 200 Jews lived in Paducah. Several of them established businesses that remained in operation for over a century.

Paducah Jews dominated the local whiskey business. Five of the six wholesale liquor firms in Paducah in 1894 were Jewish-owned. Many of these companies eventually moved into distilling. Some of their owners were among the most prominent and respected businessmen in town. Joseph Friedman started a distillery and wholesale whiskey business with his brother-in-law John Keiler in 1890. Their distillery became one of the largest in the country, producing 20,000 barrels of whiskey a year. Friedman also built and operated the Palmer Hotel and the Kentucky Theater. As president of the Commercial Club, Friedman worked to recruit industry to Paducah. He became a leading local philanthropist, creating a settlement house to help the city’s poor. When Friedman died in 1913, hundreds of vehicles took part in a procession that stretched over three miles long. After Friedman’s death, the Keiler family continued to run the business, and became major Paducah philanthropists as well. In 1923, John Keiler donated $5000 to help build a stadium behind the local high school, which was named Keiler Field. In 1930, the family donated land to the city for a park, which was named in their honor

Isaac Bernheim.

Isaac Bernheim. Photo courtesy of University of Louisville archives.

Mangold Livingston moved to Paducah by the late 1850s. His wholesale dry goods and fruit operation, M. Livingston Co., later became the largest wholesale grocery business in Kentucky. His sons and grandsons later ran the company, which remained in business until 1988. Benjamin Weille came to Paducah from Smithland just after the Civil War. A French immigrant, Weille opened a clothing store in Paducah in 1866, which became known as B. Weille & Son. His son Charles later took over the business, running it well into the 1930s. Other local Jews ran the business later in the 20th century, before the store finally closed in 1974. Henry Wallerstein opened a men’s clothing store in 1868, and was soon joined by his brothers Jacob and Melvin. In 1888, Wallerstein’s moved to a new three story building, where it remained until it closed almost a century later. Jacob ran the store until his death in 1939. His son Herbert Wallerstein then took over the local institution. Herbert became an important civic leader, getting the Paducah flood wall built after the great flood of 1937, and helping to attract the Illinois Central Railroad repair shops to the city. In 1877, brothers Mike and Mohr Michael opened a saddle and harness business. After the advent of automobiles, they switched to hardware. Mike’s son Edwin later took over the business, running it for 57 years until he closed the store in 1982.

By 1894, there were at least 31 Jewish-owned businesses in Paducah. Of these, 35% were clothing or dry goods stores. Four owned manufacturing businesses, making cigars, mineral water, candy, and saddles and harnesses. Three owned grocery or confection stores. Julius Weil left Prussia in 1866, settling in Paducah that same year. In 1868, he opened a confection manufacturing business, making various candies and cakes. Weil also owned a soda fountain which served non-alcoholic drinks of his own concoction. Jake Biederman, a native of Baden, started a grocery business in 1881; his brothers Henry and Joe later joined the operation. The Jake Biederman Grocery Company eventually included a dry goods store, an adjacent grocery store, as well as a feed and provision business. The Biederman brothers also manufactured confections and wholesaled candy and fruit. In 1894, the Biederman’s operation was one of the largest businesses in downtown Paducah.

One of the state’s most celebrated distillers got his start in Paducah. Isaac Bernheim came to the U.S. from Germany in 1868. After peddling for a time, he moved to Paducah to work in his uncle’s store. After a few months, he started working for Loeb & Bloom, a local Jewish-owned wholesale whiskey firm. In 1872, he and his brother Bernard started their own wholesale whiskey company. After the business grew significantly, they moved the operation to Louisville in 1888, where Bernheim became a major distiller and significant philanthropist.

By 1918, all three of the whiskey distilleries in Paducah were Jewish-owned. The arrival of prohibition in 1920 struck a lethal blow to these businesses. Two of them left the business permanently, with their owners retiring. Only Friedman-Keiler returned to distilling after prohibition’s repeal. The banning of alcohol led to the end of significant Jewish involvement in the liquor industry in Paducah. Afterward, most Jewish businesses were involved in retail clothing and dry goods.

By 1894, there were at least 31 Jewish-owned businesses in Paducah. Of these, 35% were clothing or dry goods stores. Four owned manufacturing businesses, making cigars, mineral water, candy, and saddles and harnesses. Three owned grocery or confection stores. Julius Weil left Prussia in 1866, settling in Paducah that same year. In 1868, he opened a confection manufacturing business, making various candies and cakes. Weil also owned a soda fountain which served non-alcoholic drinks of his own concoction. Jake Biederman, a native of Baden, started a grocery business in 1881; his brothers Henry and Joe later joined the operation. The Jake Biederman Grocery Company eventually included a dry goods store, an adjacent grocery store, as well as a feed and provision business. The Biederman brothers also manufactured confections and wholesaled candy and fruit. In 1894, the Biederman’s operation was one of the largest businesses in downtown Paducah.

One of the state’s most celebrated distillers got his start in Paducah. Isaac Bernheim came to the U.S. from Germany in 1868. After peddling for a time, he moved to Paducah to work in his uncle’s store. After a few months, he started working for Loeb & Bloom, a local Jewish-owned wholesale whiskey firm. In 1872, he and his brother Bernard started their own wholesale whiskey company. After the business grew significantly, they moved the operation to Louisville in 1888, where Bernheim became a major distiller and significant philanthropist.

By 1918, all three of the whiskey distilleries in Paducah were Jewish-owned. The arrival of prohibition in 1920 struck a lethal blow to these businesses. Two of them left the business permanently, with their owners retiring. Only Friedman-Keiler returned to distilling after prohibition’s repeal. The banning of alcohol led to the end of significant Jewish involvement in the liquor industry in Paducah. Afterward, most Jewish businesses were involved in retail clothing and dry goods.

Temple Israel's grand 1893 synagogue

Temple Israel's grand 1893 synagogue

Civic Engagement

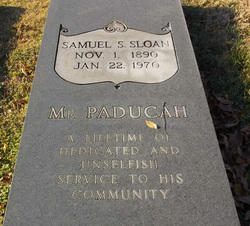

In 1966, the Paducah newspaper noted that while the Jewish population had always been small, “their service has been of the utmost character and valour” and Jews “have always been an integral part of the overall civic and industrial scene here.” Paducah Jews had long worked to improve the city. Govriel Rosenthal, who owned a successful wholesale dry goods firm, helped to create Paducah Junior College in 1932, and served as chairman of its board of trustees for seventeen years. When the school was struggling financially in its early years, Rosenthal used his personal fortune to help the school meet payroll. Later, local merchant Marshall Nemer spent 22 years on the college board, serving as chairman from 1968 to 1978. Samuel Carlick became a prominent local lawyer after World War II, serving as a city judge and as McCracken County Attorney. Sam Sloan, who had owned a retail grocery business in the early 20th century, and later sold insurance, was a beloved figure in Paducah’s civic life. He belonged to numerous local fraternal and service organizations. In 1960, the city held a “Sam Sloan Day” in his honor. After he died in 1970, he had “Mr. Paducah” carved into his gravestone, reflecting his dedication to his hometown. The author Irvin Cobb, who grew up in Paducah as close friends with several local Jews, later wrote “I was nearly grown and had to go north of the Ohio River before I knew there was such a nasty vicious thing as anti-Semitism.”

In 1966, the Paducah newspaper noted that while the Jewish population had always been small, “their service has been of the utmost character and valour” and Jews “have always been an integral part of the overall civic and industrial scene here.” Paducah Jews had long worked to improve the city. Govriel Rosenthal, who owned a successful wholesale dry goods firm, helped to create Paducah Junior College in 1932, and served as chairman of its board of trustees for seventeen years. When the school was struggling financially in its early years, Rosenthal used his personal fortune to help the school meet payroll. Later, local merchant Marshall Nemer spent 22 years on the college board, serving as chairman from 1968 to 1978. Samuel Carlick became a prominent local lawyer after World War II, serving as a city judge and as McCracken County Attorney. Sam Sloan, who had owned a retail grocery business in the early 20th century, and later sold insurance, was a beloved figure in Paducah’s civic life. He belonged to numerous local fraternal and service organizations. In 1960, the city held a “Sam Sloan Day” in his honor. After he died in 1970, he had “Mr. Paducah” carved into his gravestone, reflecting his dedication to his hometown. The author Irvin Cobb, who grew up in Paducah as close friends with several local Jews, later wrote “I was nearly grown and had to go north of the Ohio River before I knew there was such a nasty vicious thing as anti-Semitism.”

Paducah Jews After World War II

After World War II, Paducah Jews continued to concentrate in retail trade. Russian-born Sam Finkel had come to Paducah in 1919 and opened a dry goods store. Finkel’s Fair Store eventually expanded into a regional chain with eleven locations. Finkel ran the business until he died in 1967. His son-in-law Marshall Nemer then took it over. Nemer ran Finkel’s Fair Store until he retired and closed the business in 1989. Jean Shapiro operated Jeanne’s clothing store for 60 years. Other Jewish-owned stores in Paducah in the 1950s included Weille’s, Wallerstein’s, Minnen’s, Michaelson’s, the Mannis Jewelry Store, and Lookofsky’s Children’s Store. By the 1970s and 80s, many of the stores in downtown Paducah were closing after a new suburban mall opened in the area. For Jewish merchants, with most of their children having moved away to larger cities, it seemed like a good time to retire and close their businesses. By the 21st century, local Jewish-owned stores, which once dominated downtown Paducah, were a thing of the past.

After World War II, Paducah Jews continued to concentrate in retail trade. Russian-born Sam Finkel had come to Paducah in 1919 and opened a dry goods store. Finkel’s Fair Store eventually expanded into a regional chain with eleven locations. Finkel ran the business until he died in 1967. His son-in-law Marshall Nemer then took it over. Nemer ran Finkel’s Fair Store until he retired and closed the business in 1989. Jean Shapiro operated Jeanne’s clothing store for 60 years. Other Jewish-owned stores in Paducah in the 1950s included Weille’s, Wallerstein’s, Minnen’s, Michaelson’s, the Mannis Jewelry Store, and Lookofsky’s Children’s Store. By the 1970s and 80s, many of the stores in downtown Paducah were closing after a new suburban mall opened in the area. For Jewish merchants, with most of their children having moved away to larger cities, it seemed like a good time to retire and close their businesses. By the 21st century, local Jewish-owned stores, which once dominated downtown Paducah, were a thing of the past.

Former home of Finkel's Fair Store

Former home of Finkel's Fair Store

The Community Declines

Corresponding with the decline in Jewish retailing in Paducah, the local Jewish community shrank significantly in the decades after World War II. While 600 Jews lived in Paducah in 1937, only 275 did in 1960. By 1984, this number had dropped to 175. Despite this decline, Temple Israel remained active and even enjoyed its first-ever stability in rabbinic leadership. In 1949, the congregation hired Rabbi Max Kaufman, who would lead Temple Israel for the next 25 years. In 1963, the congregation moved to a new synagogue that better fit its needs. The new temple had a larger social hall and more religious school classrooms, to handle the effects of the baby boom, though its sanctuary was smaller, reflecting the decline in overall membership. By 1974, Temple Israel had 70 families.

By the time Rabbi Kaufman retired in 1974, the congregation was struggling. According to one congregation leader, only about 15 people came to Friday night services during a typical week. He reported that “we need a change to bring us together and to create a Jewish community with an atmosphere conducive to the development of ‘responsible’ Jews.” They started to bring in student rabbis from Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati in an attempt to re-energize the congregation. Temple Israel was able to rebound, and even hired a few more full-time rabbis, despite their declining membership. Rabbi Anthony Holz served as their rabbi in 1979; Howard Folb led them in 1985. Their last full-time rabbi was Joseph Spiro, who served from 1986 to 1988. Ever since, Temple Israel has relied on student rabbis. By 1998, the congregation was down to 40 families.

Corresponding with the decline in Jewish retailing in Paducah, the local Jewish community shrank significantly in the decades after World War II. While 600 Jews lived in Paducah in 1937, only 275 did in 1960. By 1984, this number had dropped to 175. Despite this decline, Temple Israel remained active and even enjoyed its first-ever stability in rabbinic leadership. In 1949, the congregation hired Rabbi Max Kaufman, who would lead Temple Israel for the next 25 years. In 1963, the congregation moved to a new synagogue that better fit its needs. The new temple had a larger social hall and more religious school classrooms, to handle the effects of the baby boom, though its sanctuary was smaller, reflecting the decline in overall membership. By 1974, Temple Israel had 70 families.

By the time Rabbi Kaufman retired in 1974, the congregation was struggling. According to one congregation leader, only about 15 people came to Friday night services during a typical week. He reported that “we need a change to bring us together and to create a Jewish community with an atmosphere conducive to the development of ‘responsible’ Jews.” They started to bring in student rabbis from Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati in an attempt to re-energize the congregation. Temple Israel was able to rebound, and even hired a few more full-time rabbis, despite their declining membership. Rabbi Anthony Holz served as their rabbi in 1979; Howard Folb led them in 1985. Their last full-time rabbi was Joseph Spiro, who served from 1986 to 1988. Ever since, Temple Israel has relied on student rabbis. By 1998, the congregation was down to 40 families.

Temple Israel's 1963 synagogue

Temple Israel's 1963 synagogue

An Important Part of the Community

Temple Israel has enjoyed close relations with local churches. Earlier in the 20th century, the congregation allowed the Broadway Methodist Church to hold services in the synagogue after their church had burned. In 1977, a local Episcopal Church donated a Star of David, which had been a part of their old slate roof, to Temple Israel to honor the close relationship between the two congregations. Even in difficult times, local churches supported Paducah’s lone Jewish congregation. When a group of teenagers painted anti-Semitic graffiti on the outside of the temple in 2004, 200 people from the larger community helped to clean up the building. Several church youth groups took part in the clean-up.

Temple Israel has enjoyed close relations with local churches. Earlier in the 20th century, the congregation allowed the Broadway Methodist Church to hold services in the synagogue after their church had burned. In 1977, a local Episcopal Church donated a Star of David, which had been a part of their old slate roof, to Temple Israel to honor the close relationship between the two congregations. Even in difficult times, local churches supported Paducah’s lone Jewish congregation. When a group of teenagers painted anti-Semitic graffiti on the outside of the temple in 2004, 200 people from the larger community helped to clean up the building. Several church youth groups took part in the clean-up.

The Jewish Community in Paducah Today

Interior of Temple Israel

Interior of Temple Israel

In 2012, Temple Israel had 32 families, most of whom were elderly. The congregation no longer has a religious school, though they continue to bring in student rabbis from Hebrew Union College once a month. While their numbers continue to decline, Paducah Jews remain committed to preserving their traditions and the long legacy of one of Kentucky’s most historic Jewish communities.