Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities

Historical Overview

|

Demopolis, the “City of the People,” had a somewhat unconventional beginning. In 1817, Congress granted the land now recognized as Marengo County to Napoleon sympathizers who had fled France after Napoleon's defeat at the Battle of Waterloo. The settlers' plan was to establish a “Vine and Olive Colony,” an agricultural settlement devoted to grape and olive cultivation. This plan quickly failed in the unforgiving Alabama wilderness. Before they moved, however, they established Demopolis on the white bluff overlooking the Tombigbee River.

Located in the heart of the “black belt,” Demopolis' fertile soil allowed the town to thrive as a cotton hub during the antebellum period. Consequently, the town was home to a high concentration of enslaved African Americans. Demopolis' location at the confluence of the Tombigbee and Tuscaloosa rivers linked the town with the Port of Mobile, a significant entry point for both Jewish and non-Jewish immigrants. |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Demopolis

The Marx Family

The first Jew to settle in Demopolis, Isaac Marx, probably arrived around 1844. A teenager coming from Germany, Marx sought refuge from Bavarian anti-Semitism, particularly restrictions on the scale of Jewish business enterprises. Marx likely came to Demopolis from either New Orleans or Mobile, port cities that often fed Jewish immigrants into smaller communities. In Demopolis, he began as a peddler, eventually encountering enough success to open a general merchandise store. He bought lots at the northeast corner of Market and Capitol streets, and built a prominent brick store there. During the Civil War, Isaac served as a Confederate quartermaster. Isaac’s son Henry continued the business until his death in 1960.

The first Jew to settle in Demopolis, Isaac Marx, probably arrived around 1844. A teenager coming from Germany, Marx sought refuge from Bavarian anti-Semitism, particularly restrictions on the scale of Jewish business enterprises. Marx likely came to Demopolis from either New Orleans or Mobile, port cities that often fed Jewish immigrants into smaller communities. In Demopolis, he began as a peddler, eventually encountering enough success to open a general merchandise store. He bought lots at the northeast corner of Market and Capitol streets, and built a prominent brick store there. During the Civil War, Isaac served as a Confederate quartermaster. Isaac’s son Henry continued the business until his death in 1960.

The Marx family became a staple of the Demopolis Jewish community throughout the nineteenth century. In 1860, Isaac Marx was worth $23,000 and owned five slaves. He had married fellow Bavarian Amelia Wiedenrich in the early 1850s. Together, they had four sons, Edward, Jacob, Julius, and Henry. The Marx sons ran a prominent business that eventually became the Marx Banking Company.

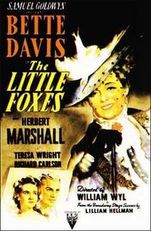

One descendant of the Marx family would gain national exposure for her career. Born in 1905 in New Orleans, playwright Lillian Hellman often visited her grandparents, heirs of both the Marx and Newhouse families, in Demopolis. The characters in Hellman’s famed play The Little Foxes, which tells the story of a wealthy, but dysfunctional Southern family, are generally considered to be based on her Demopolis family. In addition, the play’s physical settings in stately southern mansions bear strong resemblance to the residences of her Demopolis relatives. The play was later made into an acclaimed film starring Bette Davis, and it was revived on Broadway in 2017.

One descendant of the Marx family would gain national exposure for her career. Born in 1905 in New Orleans, playwright Lillian Hellman often visited her grandparents, heirs of both the Marx and Newhouse families, in Demopolis. The characters in Hellman’s famed play The Little Foxes, which tells the story of a wealthy, but dysfunctional Southern family, are generally considered to be based on her Demopolis family. In addition, the play’s physical settings in stately southern mansions bear strong resemblance to the residences of her Demopolis relatives. The play was later made into an acclaimed film starring Bette Davis, and it was revived on Broadway in 2017.

Early Settlers

Soon after Isaac Marx settled in Demopolis, other Jews began to trickle into town, most of whom would form the Jewish merchant class that came to dominate Demopolis’ commercial life. Morris Mayer, whose family had been friends of the Marxes in Germany, left his homeland at the advice of Isaac Marx. Arriving in America at New York, Mayer sold newspapers in Newark, New Jersey, until he could afford transit to Alabama in 1866. After settling in Demopolis, he went into business with another German Jew, Henry Enners. Their wholesale and retail operation was so successful that in 1872, Enners and Mayer dedicated a gleaming two-story brick building at the southwest corner of Washington and Walnut streets in the downtown. Still somewhat tied to the old country, Enners indulged in the European tradition of raising a large green bough to the roof of the store, followed by drinking and toasts, at the completion of the building.

Mayer, who eventually brought his brothers Ludwig and Simon to Demopolis, became widely known as the “Merchant Prince” of Marengo County. By one historian’s account, the Mayer brothers owned the most successful business in west Alabama, with some sources indicating that by the 1890s, they were doing a million dollars a year in sales. In 1897, such fortune allowed them to construct a magnificent three-story brick building at the corner of Walnut and Capitol, designed by architect J.G. Barnwell, in addition to occupying several adjoining buildings. The next generation of Mayers included Arthur Mayer, who became a Hollywood film executive, and Dr. Leo Mayer, a distinguished surgeon and author.

Other large Jewish clans, like the Long family, made their mark on Demopolis life as well. Born in 1848 in Vienna, Austria, Moritz Long was enticed to immigrate by an older brother running a business in Selma. Long came over, married his wife Emma from Eutaw, and started a general mercantile store in Demopolis. The business, on the corner of Walnut and Washington Streets, was nicknamed the “Long Corner” for many years. Their son, Milton Long, became heavily involved in Demopolis life, owning five downtown stores and donating vast sums of his wealth to the B’nai Jeshurun congregation, its local cemetery, and local educational causes like a school for African Americans in Greene County.

Organized Jewish Life in Demopolis

By 1858, enough Jews lived in Demopolis and the surrounding areas to establish a congregation, B'nai Jeshurun (Children of Righteousness). In 1878, the congregation bought land for a cemetery. At first, the group met in homes and empty rooms attached to congregants’ businesses, but in 1893, a temple was constructed on the corner of Main and Monroe Streets. Isaac Marx, the oldest living Jew at the dedication ceremony in 1893, lit the eternal light. B’nai Jeshurun never had a full-time rabbi. For its entire existence, the congregation’s services were led by lay readers, including Louis Mayer, Jacob Bley, George Bley, and Jerome Levy. By 1907, the congregation was a member of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, the national organization of Reform Judaism.

An Active Community

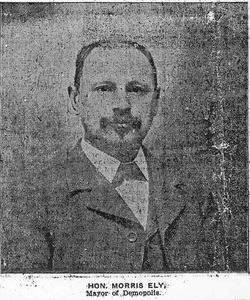

The Demopolis Jewish community of the latter half of the nineteenth century was prosperous and active. A local B’nai B’rith chapter was organized in June of 1877, with many of the town’s prominent Jewish businessmen listed as its founders. All Jewish festivals and the High Holy Days were observed. As evidenced by newspaper accounts, the Purim Ball of 1877 was a focal point of the Marengo County social calendar. This active role of the Jewish community extended to civic life as well, with three Jews, Morris Ely (1903-1906), Isidore Bley (1910), and Bony Fields (1949-1952) serving as mayors of Demopolis. Ely emigrated from Germany to Chicago in 1866, and settled in Demopolis in 1870. Ely later became the president of the Southern Grocery Company. Also born in Germany, Bley came to Demopolis around the turn of the century after his relatives had already settled in the town, and eventually opened a general merchandise store.

By 1858, enough Jews lived in Demopolis and the surrounding areas to establish a congregation, B'nai Jeshurun (Children of Righteousness). In 1878, the congregation bought land for a cemetery. At first, the group met in homes and empty rooms attached to congregants’ businesses, but in 1893, a temple was constructed on the corner of Main and Monroe Streets. Isaac Marx, the oldest living Jew at the dedication ceremony in 1893, lit the eternal light. B’nai Jeshurun never had a full-time rabbi. For its entire existence, the congregation’s services were led by lay readers, including Louis Mayer, Jacob Bley, George Bley, and Jerome Levy. By 1907, the congregation was a member of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, the national organization of Reform Judaism.

An Active Community

The Demopolis Jewish community of the latter half of the nineteenth century was prosperous and active. A local B’nai B’rith chapter was organized in June of 1877, with many of the town’s prominent Jewish businessmen listed as its founders. All Jewish festivals and the High Holy Days were observed. As evidenced by newspaper accounts, the Purim Ball of 1877 was a focal point of the Marengo County social calendar. This active role of the Jewish community extended to civic life as well, with three Jews, Morris Ely (1903-1906), Isidore Bley (1910), and Bony Fields (1949-1952) serving as mayors of Demopolis. Ely emigrated from Germany to Chicago in 1866, and settled in Demopolis in 1870. Ely later became the president of the Southern Grocery Company. Also born in Germany, Bley came to Demopolis around the turn of the century after his relatives had already settled in the town, and eventually opened a general merchandise store.

The Community Declines

In the early-twentieth century, the Demopolis Jewish community began to decline, a process that has lasted until this day. The familiar narrative of prosperous, first-generation Jewish parents watching their educated progeny leave town for good certainly applied to Demopolis. In 1905, there were around 124 Jews in Demopolis; in 1927 there were 150. By 1937, there were only 90 Jews in Demopolis. By the 1980s and early 1990s, only a handful remained.

Alan Koch

Alan Koch, whose family were long-time residents of Demopolis, achieved success in an unconventional field for the Jews of the South: baseball. Born in 1938, Koch was a baseball star at the Demopolis high school and Auburn University. After being drafted and working his way successfully through the Minor Leagues, he pitched for the Detroit Tigers and the Washington Senators of Major League Baseball in 1963 and 1964. Although later in life he lived in Montgomery, Koch spent several years doing extensive research on the history of Jews in Demopolis.

In the early-twentieth century, the Demopolis Jewish community began to decline, a process that has lasted until this day. The familiar narrative of prosperous, first-generation Jewish parents watching their educated progeny leave town for good certainly applied to Demopolis. In 1905, there were around 124 Jews in Demopolis; in 1927 there were 150. By 1937, there were only 90 Jews in Demopolis. By the 1980s and early 1990s, only a handful remained.

Alan Koch

Alan Koch, whose family were long-time residents of Demopolis, achieved success in an unconventional field for the Jews of the South: baseball. Born in 1938, Koch was a baseball star at the Demopolis high school and Auburn University. After being drafted and working his way successfully through the Minor Leagues, he pitched for the Detroit Tigers and the Washington Senators of Major League Baseball in 1963 and 1964. Although later in life he lived in Montgomery, Koch spent several years doing extensive research on the history of Jews in Demopolis.

The Jewish Community in Demopolis Today

Today, the protracted exodus of Jews from Demopolis has finally left Bert Rosenbush, Jr. as the last Jew of Demopolis and Marengo County. His grandfather, Julius Rosenbush, first settled in Demopolis in the late 1800s and established the Rosenbush Furniture Company in a building on South Walnut Avenue in 1895. After her husband's death in 1911, Essie Baum Rosenbush ran the business, eventually passing it to Bert’s father, Bert Rosenbush Sr. The scion of the Rosenbush family, Bert. Jr. ran the business from 1950 until closing it in November 2002. Bert donated the store’s impressive brick building to the city for future use as a museum of Demopolis history.

As the last Jew in Demopolis, Rosenbush, has tried to preserve the Jewish heritage of the town. Alan Koch and his brother Jack also worked to ensure that Demopolis’ important Jewish legacy has not been forgotten. In 1989, the deed for the B’nai Jeshurun’s temple was signed over for $10 to the Trinity Episcopal Church, which preserved the temple until 2007, when the sanctuary artifacts were donated to the Museum of the Southern Jewish Experience.

As the last Jew in Demopolis, Rosenbush, has tried to preserve the Jewish heritage of the town. Alan Koch and his brother Jack also worked to ensure that Demopolis’ important Jewish legacy has not been forgotten. In 1989, the deed for the B’nai Jeshurun’s temple was signed over for $10 to the Trinity Episcopal Church, which preserved the temple until 2007, when the sanctuary artifacts were donated to the Museum of the Southern Jewish Experience.