Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Tuscaloosa, Alabama

Historical Overview

|

The Tuscaloosa area was home to several successive American Indian groups from before the arrival of European explorers until the early-nineteenth century. The city itself developed on the site of a trading post that the Creek Indians established on the banks of the Black Warrior River in 1809. As Euro-American settlers increasingly encroached on the Creek lands in subsequent years, the Indians defended their territory by attacking white residents in the area. American troops soon swept in and destroyed the Creek settlement; in the ensuing treaty negotiations, the Creeks gave up legal claims to the land, which opened the territory to further settlement by white Americans and enslaved people of African descent. From across the South, Euro-American settlers streamed into the newly formed town of Tuscaloosa, their heads filled with dreams of becoming plantation owners. Located in the western part of Alabama’s soil-rich “black belt,” Tuscaloosa emerged as a commercial center of the area’s cotton economy. From 1826 to 1846, Tuscaloosa was the capital of the young state. When the capital moved eastward to Montgomery, many of the merchants and professionals moved on as well, stalling the growth of Tuscaloosa. Although it was no longer the state capital, Tuscaloosa was still the home of the state’s university, which has shaped the city and its Jewish community ever since.

Tuscaloosa suffered hard times during the Civil War when the Union Army sacked the town. Crop failures in 1867 and 1868 made economic conditions in the city worse. Not until the 1870s, when the Great Southern Railroad built tracks to the town, did Tuscaloosa begin to reemerge economically, though it never became an industrial center like Birmingham and other Alabama cities. Jews first began to settle in Tuscaloosa in significant numbers after the Civil War, as the city was struggling to get back on its feet. Jews, who concentrated in retail trade, provided access to quality goods and national markets and played an important role in the commercial development of the city. |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Tuscaloosa

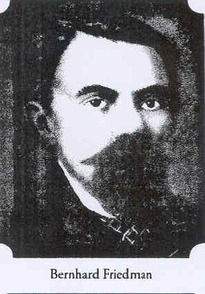

Bernard Friedman

No Tuscaloosa Jew played a more instrumental role in the city's late-nineteenth-century development than Bernard Friedman. Born in a small town outside of Budapest, Hungary, Friedman came to America in 1852 when he was only 16 years old. He started as a peddler in the South before opening a store in Atlanta in 1867. Soon after, he moved the business to Tuscaloosa. In 1870, Friedman lived in Tuscaloosa with $300 in real estate and $600 in personal property, a relatively modest amount of wealth. Over the course of the next decade, Friedman built his business into a thriving retail and wholesale operation. He partnered with Emanuel Loveman, who lived in New York and acted as a buyer for the Atlanta Store in Tuscaloosa, which was run by Friedman. His business catered to Tuscaloosa residents as well as farmers from the surrounding countryside. In one 1876 ad, the store announced that it offered a “sleeping apartment” in the wagon yard behind the store for people who had to travel a long way to get to town and needed to spend the night in Tuscaloosa. Friedman was not content with being a dry goods merchant, asking his customers to “bring along your cotton” when they came to the store. Friedman and his partner Loveman bought land all over Tuscaloosa County, which they rented out to miners, farmers, and timber companies. While writing about Friedman, the local newspaper claimed that “the operations of this active, brainy merchant extends over a large territory in Alabama.” By 1880, Friedman had moved into a grand house in the middle of town. Four African American domestic workers lived with Friedman and his family at that time.

Friedman was actively involved in the civic and economic development of Tuscaloosa. He helped to organize the first national bank in Tuscaloosa, as well as the Tuscaloosa Coal, Iron, and Land Company. He was a board member of the state hospital for the insane, which was located in Tuscaloosa. Friedman served on the city’s board of aldermen from 1882 to 1890, during which he became a passionate advocate for public education. He was instrumental in establishing Tuscaloosa’s public school system. The Friedman family remained prominent in Tuscaloosa well into the twentieth century, though they eventually joined the Presbyterian Church. The family home has been preserved as a museum by the Tuscaloosa County Preservation Society.

No Tuscaloosa Jew played a more instrumental role in the city's late-nineteenth-century development than Bernard Friedman. Born in a small town outside of Budapest, Hungary, Friedman came to America in 1852 when he was only 16 years old. He started as a peddler in the South before opening a store in Atlanta in 1867. Soon after, he moved the business to Tuscaloosa. In 1870, Friedman lived in Tuscaloosa with $300 in real estate and $600 in personal property, a relatively modest amount of wealth. Over the course of the next decade, Friedman built his business into a thriving retail and wholesale operation. He partnered with Emanuel Loveman, who lived in New York and acted as a buyer for the Atlanta Store in Tuscaloosa, which was run by Friedman. His business catered to Tuscaloosa residents as well as farmers from the surrounding countryside. In one 1876 ad, the store announced that it offered a “sleeping apartment” in the wagon yard behind the store for people who had to travel a long way to get to town and needed to spend the night in Tuscaloosa. Friedman was not content with being a dry goods merchant, asking his customers to “bring along your cotton” when they came to the store. Friedman and his partner Loveman bought land all over Tuscaloosa County, which they rented out to miners, farmers, and timber companies. While writing about Friedman, the local newspaper claimed that “the operations of this active, brainy merchant extends over a large territory in Alabama.” By 1880, Friedman had moved into a grand house in the middle of town. Four African American domestic workers lived with Friedman and his family at that time.

Friedman was actively involved in the civic and economic development of Tuscaloosa. He helped to organize the first national bank in Tuscaloosa, as well as the Tuscaloosa Coal, Iron, and Land Company. He was a board member of the state hospital for the insane, which was located in Tuscaloosa. Friedman served on the city’s board of aldermen from 1882 to 1890, during which he became a passionate advocate for public education. He was instrumental in establishing Tuscaloosa’s public school system. The Friedman family remained prominent in Tuscaloosa well into the twentieth century, though they eventually joined the Presbyterian Church. The family home has been preserved as a museum by the Tuscaloosa County Preservation Society.

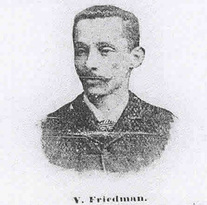

Although his children and grandchildren left the Jewish faith, Bernard Friedman played a crucial role in the development of Tuscaloosa’s Jewish community. Several of Friedman’s relatives or landsmen from Hungary joined him on the banks of the Black Warrior River. Already by 1870, three Hungarian immigrants lived with Friedman and worked in his dry goods store. One of these was Samuel Black, who had just recently emigrated from Hungary. By 1880, he had his own store in Tuscaloosa and had another more recent Hungarian immigrant boarding with him. The Black family became longtime merchants in Tuscaloosa and pillars of the local Jewish community. Many other Hungarian Jews followed the lead of Friedman and Black, making Tuscaloosa their home. Victor and Ike Friedman, who were likely related to Bernard Friedman, came to Tuscaloosa from Hungary and opened stores by 1900. Victor got his start in town by working as a clerk in Bernard’s store. Adolph Holzstein left Hungary in 1873, settling in Tuscaloosa by the late 1880s. Sam Wiesel came to the United States from Hungary in 1901. By 1920, he owned a small clothing store in Tuscaloosa. The Wiesel family remained active in Tuscaloosa’s economic and Jewish life for much of the twentieth century.

A Growing Community

While Hungarian Jews dominated the early Tuscaloosa Jewish community, others came from Germany. Herman Rosenau left Bavaria in 1852 and lived in New York and Charleston, South Carolina, before moving to Montevallo, Alabama in 1860. Wounded fighting for the Confederacy at the Battle of the Wilderness, he later settled in Tuscaloosa. In 1885, Rosenau and Victor Friedman bought out Bernard Friedman and Emanuel Loveman’s Atlanta Store, which was described in the local newspaper as an “elegant dry goods emporium.” In 1894, the partners bought out Friedman and Loveman’s wholesale operation as well. Herman’s son David became a local industrialist, in addition to a dry goods merchant, opening three cotton hosiery mills in the area, which employed hundreds of people.

While Hungarian Jews dominated the early Tuscaloosa Jewish community, others came from Germany. Herman Rosenau left Bavaria in 1852 and lived in New York and Charleston, South Carolina, before moving to Montevallo, Alabama in 1860. Wounded fighting for the Confederacy at the Battle of the Wilderness, he later settled in Tuscaloosa. In 1885, Rosenau and Victor Friedman bought out Bernard Friedman and Emanuel Loveman’s Atlanta Store, which was described in the local newspaper as an “elegant dry goods emporium.” In 1894, the partners bought out Friedman and Loveman’s wholesale operation as well. Herman’s son David became a local industrialist, in addition to a dry goods merchant, opening three cotton hosiery mills in the area, which employed hundreds of people.

Organized Jewish Life in Tuscaloosa

It took several decades for Tuscaloosa Jews to organize a congregation. In 1903, a group founded Temple Emanu-El. In the congregation’s early years, the members met monthly for Reform services led by Rabbi Morris Newfield of Birmingham’s Temple Emanu-El. In 1907, the congregation had fourteen members and an annual income of $180. The two leading officers of the congregation, President Adolph Holzstein and Treasurer Ike Friedman, were both Hungarian immigrants. Although the congregation was small, its members were relatively young, and they had 26 children in their religious school. That year they met for High Holiday services at Tuscaloosa’s city hall. In 1912, the congregation bought a former church on Broad Street for $1,700. Paying $600 down, Emanu-El paid off the remaining $1,100 promissory note in 1914. The local newspaper pronounced that the temple “presents a splendid appearance.” That year, High Holiday services were lay-led, though the congregation brought down Isadore Sperling, a Hebrew school teacher from Birmingham, to give the Yom Kippur sermons. The congregation struggled in its early years. In 1919, Emanu-El had only ten dues paying members and held services only on the High Holidays.

By 1925, the congregation had joined the Reform Union of American Hebrew Congregations. Tuscaloosa Jews who did not like the classical Reform style of Temple Emanu-El formed their own traditional congregation, though this group was always smaller than Emanu-El. This informal group was meeting at the University of Alabama Hillel House when they decided to merge with Emanu-El around 1947. Despite their original differences, the merger occurred relatively easily, with few ritual disputes.

It took several decades for Tuscaloosa Jews to organize a congregation. In 1903, a group founded Temple Emanu-El. In the congregation’s early years, the members met monthly for Reform services led by Rabbi Morris Newfield of Birmingham’s Temple Emanu-El. In 1907, the congregation had fourteen members and an annual income of $180. The two leading officers of the congregation, President Adolph Holzstein and Treasurer Ike Friedman, were both Hungarian immigrants. Although the congregation was small, its members were relatively young, and they had 26 children in their religious school. That year they met for High Holiday services at Tuscaloosa’s city hall. In 1912, the congregation bought a former church on Broad Street for $1,700. Paying $600 down, Emanu-El paid off the remaining $1,100 promissory note in 1914. The local newspaper pronounced that the temple “presents a splendid appearance.” That year, High Holiday services were lay-led, though the congregation brought down Isadore Sperling, a Hebrew school teacher from Birmingham, to give the Yom Kippur sermons. The congregation struggled in its early years. In 1919, Emanu-El had only ten dues paying members and held services only on the High Holidays.

By 1925, the congregation had joined the Reform Union of American Hebrew Congregations. Tuscaloosa Jews who did not like the classical Reform style of Temple Emanu-El formed their own traditional congregation, though this group was always smaller than Emanu-El. This informal group was meeting at the University of Alabama Hillel House when they decided to merge with Emanu-El around 1947. Despite their original differences, the merger occurred relatively easily, with few ritual disputes.

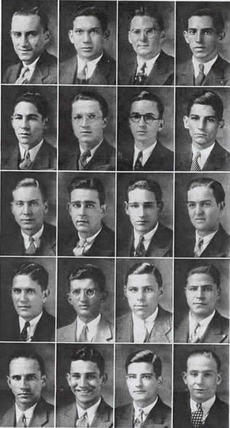

University of Alabama

The Tuscaloosa Jewish community has long had close ties to the University of Alabama. A number of Tuscaloosa Jews attended the state university. Victor Hugo Friedman, the son of Bernard, graduated from the university in the late 1890s, and remained devoted to his alma mater throughout his life. Today, the Friedman Hall dormitory is named after him. Jewish students from across Alabama attended the university, prompting a statewide fundraising campaign to build a Hillel House, which was established in 1934. Beginning in the 1920s, a number of Jews from the northeast began to arrive at the university. While many eastern colleges had quotas to restrict the enrollment of Jewish students, the University of Alabama President George Denny actively encouraged them to come to Tuscaloosa, as the out-of-state tuition benefited the financially struggling university. In the mid-1930s, there were three Jewish fraternities, including Kappa Nu, and two Jewish sororities on the campus. By 1951, there were 600 Jewish students attending the University of Alabama. The local Jewish community often took these students in, hosting them for the high holidays and even helping them financially if needed.

This influx of Northern Jewish students sometimes led to tensions on the campus. According to the writer William Bradford Huie, who attended the university in the late 1920s, these Jews brought a more competitive and academic focus to their schoolwork which often clashed with the more slow-paced, genteel culture of the college. These Jews were not welcomed into the existing Greek system, forming their own all-Jewish fraternities and sororities instead. As Huie wrote in his autobiographical novel Mud on the Stars, “there was no denying that the Jews were the most aggressive intellectual force at the University of Alabama.” Jewish enrollment dropped in the late 1950s in the wake of the state’s opposition to integration at the university. The sometimes violent unrest scared many Jewish parents, who sent their children to more peaceful universities.

The Tuscaloosa Jewish community has long had close ties to the University of Alabama. A number of Tuscaloosa Jews attended the state university. Victor Hugo Friedman, the son of Bernard, graduated from the university in the late 1890s, and remained devoted to his alma mater throughout his life. Today, the Friedman Hall dormitory is named after him. Jewish students from across Alabama attended the university, prompting a statewide fundraising campaign to build a Hillel House, which was established in 1934. Beginning in the 1920s, a number of Jews from the northeast began to arrive at the university. While many eastern colleges had quotas to restrict the enrollment of Jewish students, the University of Alabama President George Denny actively encouraged them to come to Tuscaloosa, as the out-of-state tuition benefited the financially struggling university. In the mid-1930s, there were three Jewish fraternities, including Kappa Nu, and two Jewish sororities on the campus. By 1951, there were 600 Jewish students attending the University of Alabama. The local Jewish community often took these students in, hosting them for the high holidays and even helping them financially if needed.

This influx of Northern Jewish students sometimes led to tensions on the campus. According to the writer William Bradford Huie, who attended the university in the late 1920s, these Jews brought a more competitive and academic focus to their schoolwork which often clashed with the more slow-paced, genteel culture of the college. These Jews were not welcomed into the existing Greek system, forming their own all-Jewish fraternities and sororities instead. As Huie wrote in his autobiographical novel Mud on the Stars, “there was no denying that the Jews were the most aggressive intellectual force at the University of Alabama.” Jewish enrollment dropped in the late 1950s in the wake of the state’s opposition to integration at the university. The sometimes violent unrest scared many Jewish parents, who sent their children to more peaceful universities.

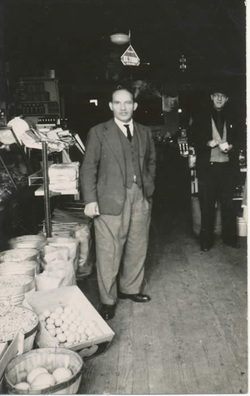

Alex Kartzinel in his store circa 1940.

Alex Kartzinel in his store circa 1940.

Twentieth-Century Jewish Businesses

Through much of the twentieth century, the Tuscaloosa Jewish community was still heavily concentrated in retail trade. Max Pizitz was a Russian-born immigrant who owned a small store in Birmingham before moving to Tuscaloosa by 1919. His Pizitz Mercantile Company called itself “the store of cash prices.” The two Wiesel brothers each owned stores; one carried women’s clothes, the other men’s clothes. Black, Friedman, and Winston was another longtime Jewish-owned store in Tuscaloosa. The Kartzinel family ran a feed and seed store and deli that would import bagels and pumpernickel bread from Birmingham. When the shipment arrived by bus, they would call the other Jews in town informing them that the “bread’s in.” The Temerson family owned a scrap metal business. Morris Sokol had a successful furniture store and became a local philanthropist and civic leader, serving on the local parks commission board. Morris Sokol Park was named in his honor. Many of these Jewish owned stores began to close in the 1960s, and were largely gone by the 1970s.

While the decline of the Jewish merchant class affected many other small Jewish communities, Tuscaloosa has managed to thrive in spite of it due to the presence of the university. Harry Lipson was among the first in a growing wave of Jewish academics hired to teach at the University of Alabama, arriving in the late 1940s. Lipson taught business and marketing at Alabama for 40 years. He and his wife Miriam were extremely active in Temple Emanu-El. In Tuscaloosa, Jews affiliated with the university replaced the Jewish merchants who had previously filled the pews at Temple Emanu-El. This influx resulted in the peak of Tuscaloosa’s Jewish population in the 1970s and 1980s. By 1980, an estimated 315 Jews lived in Tuscaloosa, up from 210 in 1948. The congregation’s religious school reached a peak of around fifty students during the 1980s.

Through much of the twentieth century, the Tuscaloosa Jewish community was still heavily concentrated in retail trade. Max Pizitz was a Russian-born immigrant who owned a small store in Birmingham before moving to Tuscaloosa by 1919. His Pizitz Mercantile Company called itself “the store of cash prices.” The two Wiesel brothers each owned stores; one carried women’s clothes, the other men’s clothes. Black, Friedman, and Winston was another longtime Jewish-owned store in Tuscaloosa. The Kartzinel family ran a feed and seed store and deli that would import bagels and pumpernickel bread from Birmingham. When the shipment arrived by bus, they would call the other Jews in town informing them that the “bread’s in.” The Temerson family owned a scrap metal business. Morris Sokol had a successful furniture store and became a local philanthropist and civic leader, serving on the local parks commission board. Morris Sokol Park was named in his honor. Many of these Jewish owned stores began to close in the 1960s, and were largely gone by the 1970s.

While the decline of the Jewish merchant class affected many other small Jewish communities, Tuscaloosa has managed to thrive in spite of it due to the presence of the university. Harry Lipson was among the first in a growing wave of Jewish academics hired to teach at the University of Alabama, arriving in the late 1940s. Lipson taught business and marketing at Alabama for 40 years. He and his wife Miriam were extremely active in Temple Emanu-El. In Tuscaloosa, Jews affiliated with the university replaced the Jewish merchants who had previously filled the pews at Temple Emanu-El. This influx resulted in the peak of Tuscaloosa’s Jewish population in the 1970s and 1980s. By 1980, an estimated 315 Jews lived in Tuscaloosa, up from 210 in 1948. The congregation’s religious school reached a peak of around fifty students during the 1980s.

Emanu-El in the twentieth Century

By 1958, the congregation had outgrown its temple and bought a former Methodist Church on 10th Street, just three blocks from the campus’ legendary football stadium. The new location gave Emanu-El’s temple youth group a sure-fire fundraiser as they charged Crimson Tide fans to park at the temple on game days. Not long after moving into their new home, Temple Emanu-El outgrew the facility and began to look for a new site. In the late 1960s, they bought land on Skyland Boulevard, and built a temple on the site in 1971. Morris Sokol led the way, donating the lead gift in the effort to raise the money for the new building. The sanctuary of the new temple was named after him.

Temple Emanu-El hired its first full-time rabbi, Joseph Asher, in the mid-1950s. Rabbi Asher only stayed a few years before being replaced by Rabbi Elijah Palnick in 1960. These rabbis often had joint appointments with Hillel or the University of Alabama Religion Department, and served the congregation in a part-time capacity. Most did not stay very long. The exception was Leon Weinberger, who taught religion at Alabama and served the congregation as rabbi for many years before becoming rabbi emeritus.

By 1958, the congregation had outgrown its temple and bought a former Methodist Church on 10th Street, just three blocks from the campus’ legendary football stadium. The new location gave Emanu-El’s temple youth group a sure-fire fundraiser as they charged Crimson Tide fans to park at the temple on game days. Not long after moving into their new home, Temple Emanu-El outgrew the facility and began to look for a new site. In the late 1960s, they bought land on Skyland Boulevard, and built a temple on the site in 1971. Morris Sokol led the way, donating the lead gift in the effort to raise the money for the new building. The sanctuary of the new temple was named after him.

Temple Emanu-El hired its first full-time rabbi, Joseph Asher, in the mid-1950s. Rabbi Asher only stayed a few years before being replaced by Rabbi Elijah Palnick in 1960. These rabbis often had joint appointments with Hillel or the University of Alabama Religion Department, and served the congregation in a part-time capacity. Most did not stay very long. The exception was Leon Weinberger, who taught religion at Alabama and served the congregation as rabbi for many years before becoming rabbi emeritus.

The Jewish Community in Tuscaloosa Today

Members of Emanu-El parade the Torah

Members of Emanu-El parade the Torah to their new synagogue in 2010

In recent years, the congregation has experienced a drop in its membership, going from eighty-nine member households in 1990 to fifty in 2008. Most of the children raised in the congregation do not return to Tuscaloosa, so the Jewish community must attract new residents to maintain its population. While Jewish scholars and professionals are still attracted to Tuscaloosa to work at the University of Alabama, many of them choose not to affiliate with Emanu-El.

The congregation had shrunk to the point where their temple on Skyland Boulevard was too big and too expensive to maintain. In 2007, the congregation sold the building to the Alabama School for the Deaf and Blind, using the proceeds to fund a new temple located on the campus of the university. Emanu-El dedicated its new synagogue in 2010; a new campus Hillel Center was opened the following year serving an estimated 600 Jewish students at the university.

The university hopes that these new buildings will attract more Jewish students and faculty, while the congregation hopes that its new location will encourage more Jews at the university to affiliate with Emanu-El. As of 2011, Emanu-El had sixty-eight member families and twenty children in its religious school.

The presence of the university has helped the community survive the disappearance of the Jewish merchant class, which has decimated other small southern Jewish communities. With the school’s increased Jewish recruitment and the new on-campus temple, ties between the university and the Tuscaloosa Jewish community should only increase.

The congregation had shrunk to the point where their temple on Skyland Boulevard was too big and too expensive to maintain. In 2007, the congregation sold the building to the Alabama School for the Deaf and Blind, using the proceeds to fund a new temple located on the campus of the university. Emanu-El dedicated its new synagogue in 2010; a new campus Hillel Center was opened the following year serving an estimated 600 Jewish students at the university.

The university hopes that these new buildings will attract more Jewish students and faculty, while the congregation hopes that its new location will encourage more Jews at the university to affiliate with Emanu-El. As of 2011, Emanu-El had sixty-eight member families and twenty children in its religious school.

The presence of the university has helped the community survive the disappearance of the Jewish merchant class, which has decimated other small southern Jewish communities. With the school’s increased Jewish recruitment and the new on-campus temple, ties between the university and the Tuscaloosa Jewish community should only increase.