Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Decatur, Alabama

Historical Overview

|

While the Jewish population of Decatur never rivaled that of nearby Huntsville, the north central Alabama town still has a significant Jewish history. Located 81 miles north of Birmingham, Decatur experienced economic success in the nineteenth century due to its location along the Tennessee River and along several railroad cargo routes. Geographically within the Tennessee Valley, Decatur became a manufacturing center. In the nineteenth century Decatur gained a reputation as a wild town, with plenty of establishments that catered to the vices of travelers passing through. In the twentieth century, Decatur continued to experience solid economic growth, though it was eclipsed by Huntsville as the regional economic hub after World War II, due to Huntsville's aerospace and military installations.

The Jewish community of Decatur began in the mid-nineteenth century and continues to the present. |

RESOURCES

Jewish Cemetery List |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Decatur

Early Settlers

Louis Falk emigrated from Prussia in 1856, first settling in Philadelphia, and then later in New York. He moved to Florence, Alabama in 1857. After clerking in a store for a while, he opened his own business in a rural town 22 miles south of Decatur. The town, which became a stop on the L&N Railroad, took the merchant’s name as its own, Falkville. After serving in the Confederate Army during the Civil War, he joined his uncle in a business in Danville, Alabama. In 1869, Falk moved to Decatur to open a furniture store, which remained in business for several decades. A local publisher described Falk as “one of the leading and progressive business men of this section.”

Max Cohn came to the United States from Germany in 1873; in 1880 he opened a dry goods store on Bank Street in Decatur. The local newspaper called Cohn “a wide-awake and progressive business man.”

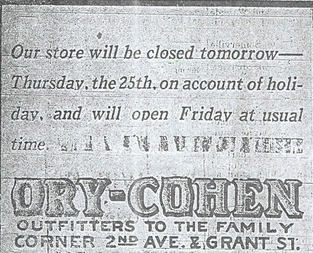

Early Jewish settlers like Falk and Cohn were soon joined by others as Jewish-owned businesses sprouted up in downtown Decatur. According to a local city directory from the early-twentieth century, of sixteen dry goods stores in Decatur, seven were owned by Jews, all but one of which were located in Bank Street, the town’s main business thoroughfare. Sam Frank owned a home furnishings store. Harold Michelson, whose parents Max and Ruth began the business, sold fancy clothes, frequently bought by the local bordello workers who needed impressive wardrobes for their occupation. Harry Olshine came to the United States from Russian Poland with his older brother Abraham in 1905, at the age of 15. After working as a traveling peddler based out of Jackson, Tennessee, Olshine moved to Decatur and opened a clothing store named Olshine’s. Olshine was quite successful; by 1920, he was able to afford a live-in cook to help his wife Teresa and their two young children. Russian-born Eli Cohen, who first settled in England, came to the United States in 1912. By 1920, he was living in Decatur with his wife and three children and owned a grocery store. Aaron Cohen and Samuel Ory owned a dry goods store together, named Ory-Cohen. These Jewish merchants would close their stores for the High Holidays, running ads in the local newspaper to inform their customers.

Louis Falk emigrated from Prussia in 1856, first settling in Philadelphia, and then later in New York. He moved to Florence, Alabama in 1857. After clerking in a store for a while, he opened his own business in a rural town 22 miles south of Decatur. The town, which became a stop on the L&N Railroad, took the merchant’s name as its own, Falkville. After serving in the Confederate Army during the Civil War, he joined his uncle in a business in Danville, Alabama. In 1869, Falk moved to Decatur to open a furniture store, which remained in business for several decades. A local publisher described Falk as “one of the leading and progressive business men of this section.”

Max Cohn came to the United States from Germany in 1873; in 1880 he opened a dry goods store on Bank Street in Decatur. The local newspaper called Cohn “a wide-awake and progressive business man.”

Early Jewish settlers like Falk and Cohn were soon joined by others as Jewish-owned businesses sprouted up in downtown Decatur. According to a local city directory from the early-twentieth century, of sixteen dry goods stores in Decatur, seven were owned by Jews, all but one of which were located in Bank Street, the town’s main business thoroughfare. Sam Frank owned a home furnishings store. Harold Michelson, whose parents Max and Ruth began the business, sold fancy clothes, frequently bought by the local bordello workers who needed impressive wardrobes for their occupation. Harry Olshine came to the United States from Russian Poland with his older brother Abraham in 1905, at the age of 15. After working as a traveling peddler based out of Jackson, Tennessee, Olshine moved to Decatur and opened a clothing store named Olshine’s. Olshine was quite successful; by 1920, he was able to afford a live-in cook to help his wife Teresa and their two young children. Russian-born Eli Cohen, who first settled in England, came to the United States in 1912. By 1920, he was living in Decatur with his wife and three children and owned a grocery store. Aaron Cohen and Samuel Ory owned a dry goods store together, named Ory-Cohen. These Jewish merchants would close their stores for the High Holidays, running ads in the local newspaper to inform their customers.

Organized Jewish Life in Decatur

By the early-twentieth century, there were enough Jews in Decatur to form a congregation. B’nai Jacob was founded in 1916, but was small and short-lived. By 1919, it had 22 members. M.S. Barnett, a sixty-seven-year-old, German-born dry goods merchant, was the president of the congregation, while Ike J. Kuhn was the secretary. The group met in a local Masonic lodge, never owning their own building. The Hebrew school had two classes, two teachers, and sixteen students in 1919. They also bought land for a Jewish burial ground within the larger city cemetery. The congregation seems to have disbanded sometime before World War II, as Decatur Jews began to travel to nearby Huntsville or Florence for services.

Civically Engaged

Jews were generally accepted into the civic life of Decatur. In the late-nineteenth century, Louis Falk was a significant booster of the local economy. He was involved with various local industries and institutions, serving on the boards of the Morgan County Building and Loan Association, South & North Railway Company, and the First National Bank. He belonged to several local fraternal societies, including the Masons and the Knight of Pythias, as well as B’nai B’rith. He also served on the local school board and as a city alderman. Although Jews were seen as different by the Christian majority, they enjoyed social acceptance for the most part. Jews were allowed to join the local country club, and intermarriage between local Jews and Gentiles was also common throughout the twentieth century.

By the early-twentieth century, there were enough Jews in Decatur to form a congregation. B’nai Jacob was founded in 1916, but was small and short-lived. By 1919, it had 22 members. M.S. Barnett, a sixty-seven-year-old, German-born dry goods merchant, was the president of the congregation, while Ike J. Kuhn was the secretary. The group met in a local Masonic lodge, never owning their own building. The Hebrew school had two classes, two teachers, and sixteen students in 1919. They also bought land for a Jewish burial ground within the larger city cemetery. The congregation seems to have disbanded sometime before World War II, as Decatur Jews began to travel to nearby Huntsville or Florence for services.

Civically Engaged

Jews were generally accepted into the civic life of Decatur. In the late-nineteenth century, Louis Falk was a significant booster of the local economy. He was involved with various local industries and institutions, serving on the boards of the Morgan County Building and Loan Association, South & North Railway Company, and the First National Bank. He belonged to several local fraternal societies, including the Masons and the Knight of Pythias, as well as B’nai B’rith. He also served on the local school board and as a city alderman. Although Jews were seen as different by the Christian majority, they enjoyed social acceptance for the most part. Jews were allowed to join the local country club, and intermarriage between local Jews and Gentiles was also common throughout the twentieth century.

Holocaust Survivors in Decatur

After World War II, a few Holocaust survivors, including Julian and Frances Hershfeld, settled in Decatur. Highly educated in Warsaw, Julian was a child prodigy on the piano, and eventually attended the Sorbonne. He ultimately graduated with a doctorate in Textile Science. Arrested by the Nazis, he was sent to the Lodz Ghetto, where he met Frances. The Nazis soon transferred him to Auschwitz and then ultimately to the Buchenwald concentration camp. He was made a slave laborer for a pharmaceutical company, a task that left him with permanent damage to his lungs. As the liberating Russians drew near to the camp in 1945, the Nazis moved to expedite their mass murders. Julian was so emaciated that he was covered up with a burlap sack and left for dead. After Buchenwald was liberated and Hershfeld was discovered alive, he reunited with Frances; they married in 1946. They eventually moved to Decatur and had two children. Julian had a successful career in Decatur working as a textile scientist for a major corporation. He later moved to Gastonia, North Carolina, where he passed away due to the chemical scars inflicted by the Nazis decades earlier.

After World War II, a few Holocaust survivors, including Julian and Frances Hershfeld, settled in Decatur. Highly educated in Warsaw, Julian was a child prodigy on the piano, and eventually attended the Sorbonne. He ultimately graduated with a doctorate in Textile Science. Arrested by the Nazis, he was sent to the Lodz Ghetto, where he met Frances. The Nazis soon transferred him to Auschwitz and then ultimately to the Buchenwald concentration camp. He was made a slave laborer for a pharmaceutical company, a task that left him with permanent damage to his lungs. As the liberating Russians drew near to the camp in 1945, the Nazis moved to expedite their mass murders. Julian was so emaciated that he was covered up with a burlap sack and left for dead. After Buchenwald was liberated and Hershfeld was discovered alive, he reunited with Frances; they married in 1946. They eventually moved to Decatur and had two children. Julian had a successful career in Decatur working as a textile scientist for a major corporation. He later moved to Gastonia, North Carolina, where he passed away due to the chemical scars inflicted by the Nazis decades earlier.

|

After World War II

Other Jews moved to Decatur after the war. Morley Denbo, having grown up in Pulaski, Tennessee, arrived in Decatur in 1950 with his wife Barbara and daughter Leslie. He had served in the U.S. Navy in the waning days of World War II, and subsequently resumed his college education at the University of Alabama. From there, he worked in Bristol, Tennessee, at his father-in-law’s scrap metal business before deciding to buy his uncle’s firm in Decatur. By the time he reached the town, the congregation was no longer active and most Jews had left. Yet, over the next half-century, he built his scrap metal business into a major commercial empire; today, his son Joel runs the business, now called Tennessee Valley Recycling. |

The Jewish Community in Decatur Today

There are hardly any population estimates for the Decatur Jewish community in the past. One survey in 1937 found that 50 Jews lived in town. While the exact figures are unknown, it’s clear that the Decatur Jewish community was never large. In recent decades, it has become even smaller. In 2009, only about fifteen Jews lived in Decatur.