Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Huntsville, Alabama

Historical Overview

Stories of the Jewish Community in Huntsville

Early Settlers

It remains unclear when the earliest Jewish settlers, most of whom were German-born, arrived in Huntsville, but most records suggest the presence of the Andrew brothers from 1829 until 1837. Zalegman and Joseph Andrew purchased a lot on the south side of the town’s public square in April 1829, establishing a business with the name “Andrews and Brothers.” The Panic of 1837, however, destroyed the operation and sent the remaining brothers to New Orleans and Mobile.

While it is likely that other Jews had come to Huntsville during the 1840s, two men, Robert Herstein and Morris Bernstein, were among the first Jews to sink roots in the town. Both had settled in Huntsville by 1859, as that year’s city directory listed them as residents and business owners. Herstein was a dealer in “clothing and furniture goods” while Bernstein was a jeweler before he became involved in real estate. Both were born in Germany, but came to Huntsville through different routes. Bernstein settled in Baltimore, Maryland before heading south and marrying Huntsvillian Henrietta Newman in 1852. Herstein first settled in Leesburg, Virginia, from where he subsequently moved to Huntsville in 1855. Four years later, he married a Baltimore Jew, Rosa Blimline, with whom he eventually had seven children. Both Herstein and Bernstein became business leaders in Huntsville, serving on the board of the local bank. Herstein served as city treasurer during the Reconstruction Era.

Another pair of German Jews, Daniel and Solomon Schiffman, were sixteen and twenty-two years of age when they arrived in Huntsville in 1857. They had previously lived in the bluegrass plains of Kentucky and in Cincinnati, and went into the clothing and dry goods businesses after settling in Huntsville. After both married Jewish women from Cincinnati and started families, they became active within both the Jewish and larger communities. Solomon was a founding member of B’nai Sholom, and an active member of B’nai B’rith, while Daniel served on the City Council in the 1880s. Their nephew, Isaac Schiffman, came from his homeland of Germany to join his uncles in 1875. He worked with his uncles in the mercantile business, but eventually transitioned to investments and cotton brokering.

It remains unclear when the earliest Jewish settlers, most of whom were German-born, arrived in Huntsville, but most records suggest the presence of the Andrew brothers from 1829 until 1837. Zalegman and Joseph Andrew purchased a lot on the south side of the town’s public square in April 1829, establishing a business with the name “Andrews and Brothers.” The Panic of 1837, however, destroyed the operation and sent the remaining brothers to New Orleans and Mobile.

While it is likely that other Jews had come to Huntsville during the 1840s, two men, Robert Herstein and Morris Bernstein, were among the first Jews to sink roots in the town. Both had settled in Huntsville by 1859, as that year’s city directory listed them as residents and business owners. Herstein was a dealer in “clothing and furniture goods” while Bernstein was a jeweler before he became involved in real estate. Both were born in Germany, but came to Huntsville through different routes. Bernstein settled in Baltimore, Maryland before heading south and marrying Huntsvillian Henrietta Newman in 1852. Herstein first settled in Leesburg, Virginia, from where he subsequently moved to Huntsville in 1855. Four years later, he married a Baltimore Jew, Rosa Blimline, with whom he eventually had seven children. Both Herstein and Bernstein became business leaders in Huntsville, serving on the board of the local bank. Herstein served as city treasurer during the Reconstruction Era.

Another pair of German Jews, Daniel and Solomon Schiffman, were sixteen and twenty-two years of age when they arrived in Huntsville in 1857. They had previously lived in the bluegrass plains of Kentucky and in Cincinnati, and went into the clothing and dry goods businesses after settling in Huntsville. After both married Jewish women from Cincinnati and started families, they became active within both the Jewish and larger communities. Solomon was a founding member of B’nai Sholom, and an active member of B’nai B’rith, while Daniel served on the City Council in the 1880s. Their nephew, Isaac Schiffman, came from his homeland of Germany to join his uncles in 1875. He worked with his uncles in the mercantile business, but eventually transitioned to investments and cotton brokering.

The Civil War

By the Civil War, Jews were beginning to assimilate into Huntsville community life. During the fighting, most local Jews supported the Confederacy, a stance common throughout the South. In fact, Morris and Henrietta Bernstein bought and owned slaves during this time. An 1859 receipt confirms their purchase of an enslaved African American woman named Sally for $500, followed by the acquisition of an eight-year-old boy named Virgil for the price of $22.50 in 1861. Local Jews also supported the Confederate cause, and some even served within its ranks, including Daniel Schiffman.

Civic Engagement

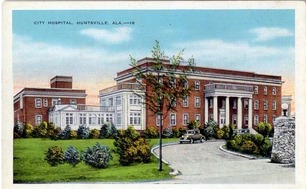

Huntsville Jews were very active in the larger community. Morris Bernstein’s daughter, Betty Goldsmith, helped to found a local charitable organization and was instrumental in convincing city leaders to build the city hospital. The Goldsmith and Schiffman families later donated land to the city for use as a ball field. Their descendent, Margaret Anne Goldsmith, donated 300 acres of land to the city in 2003 for use as the Goldsmith Schiffman Wildlife Preserve.

By the Civil War, Jews were beginning to assimilate into Huntsville community life. During the fighting, most local Jews supported the Confederacy, a stance common throughout the South. In fact, Morris and Henrietta Bernstein bought and owned slaves during this time. An 1859 receipt confirms their purchase of an enslaved African American woman named Sally for $500, followed by the acquisition of an eight-year-old boy named Virgil for the price of $22.50 in 1861. Local Jews also supported the Confederate cause, and some even served within its ranks, including Daniel Schiffman.

Civic Engagement

Huntsville Jews were very active in the larger community. Morris Bernstein’s daughter, Betty Goldsmith, helped to found a local charitable organization and was instrumental in convincing city leaders to build the city hospital. The Goldsmith and Schiffman families later donated land to the city for use as a ball field. Their descendent, Margaret Anne Goldsmith, donated 300 acres of land to the city in 2003 for use as the Goldsmith Schiffman Wildlife Preserve.

Organized Jewish Life in Huntsville

By the 1870s, Huntsville had amassed enough Jews to merit the formation of Jewish institutions. In 1875, they founded a local chapter of B’nai B’rith. A year later, Huntsville Jews formed Congregation B’nai Sholom, or “Sons of Peace.”

The new congregation counted thirty-two men among its founding members and met at the Masonic Hall for services in that year. Besides long-established figures like Schiffman and Herstein, Jews such as Abraham Newman, a 52-year-old, Prussian-born dry goods merchant, and Bernard Wise, another German-born dry goods merchant, 64-years-old, were present.

The new congregation immediately defined its terms of existence and religious preferences in their constitution. Like most other Southern congregations, B’nai Shalom adhered to the Reform Judaism of Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise in Cincinnati. As such, Wise’s prayer book, Minhag America, served as a basis for the new congregation’s services.

As evidenced by the constitution, the members of B’nai Sholom placed special emphasis on the strict maintenance of decorum, both in temple administrative business and prayer services. First, the constitution provided for the warning that “any member marrying out of the pale of the Jewish religion forfeits his membership.” The constitution also dealt sternly with more mundane ordinances, such as that everyone must “conform strictly” to the regulations respecting the time when the congregation was standing or sitting. Another provision cites the unannounced withdrawal from a congregation meeting as grounds for a one dollar fine. Such stipulations suggest that the founding members were deeply concerned with the coherence and stability of the nascent congregation.

In its early years, money was often an issue for the congregation. They struggled to furnish their rented room in time for the High Holidays in 1876. Members who fell behind on their dues were suspended and their names published in the nationally circulated American Israelite newspaper. Of their 32 founding members in 1876, only 15 were still contributing members by 1878; 11 had been suspended for failure to pay dues. The Ladies Hebrew Charity Society supported the congregation, holding a charity ball that raised money to refurbish their meeting room in 1885.

Despite these financial woes, B’nai Sholom worked to establish itself as the centerpiece of a burgeoning community. In 1877, the board approved a motion to join the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, although it left two years later because of the financial burden of membership; over its early years, B’nai Sholom would join and then leave the UAHC several times due to financial concerns. For over 11 years, Abe Newman, a Bavarian-born merchant, led services and oversaw the religious school. When Newman died in 1890, the congregation decided to seek its first full-time rabbi. After a few years of hosting student rabbis, the congregation hired Rabbi A.M Bloch of Port Gibson, Mississippi in November of 1892. His tenure lasted less than a year due to congregants’ disapproval of his sermons, which they found to be “distasteful to the entire membership of the congregation.” Apparently, Bloch was very critical of members who did not attend services, and singled them out personally during his sermons. He was replaced by a unanimous decision of the board by Rabbi I.E. Wagenheim, the first in a line of seven rabbis who served the congregation from one to three years.

Many lay leaders had been involved in leadership positions at B’nai Sholom in its early history, especially before the search for a full-time rabbi began in 1890. However, in a truly unusual move to fill a pulpit vacancy created by an ill rabbi in 1905, a local Episcopal minister, Rev. Claybrook, volunteered his services for Friday night services, which the Temple board accepted. This incident reveals how integrated B’nai Sholom was in the city’s religious life, and how Reform their services were. A Christian minister would only be able to lead services if they were largely in English rather than Hebrew.

By the 1870s, Huntsville had amassed enough Jews to merit the formation of Jewish institutions. In 1875, they founded a local chapter of B’nai B’rith. A year later, Huntsville Jews formed Congregation B’nai Sholom, or “Sons of Peace.”

The new congregation counted thirty-two men among its founding members and met at the Masonic Hall for services in that year. Besides long-established figures like Schiffman and Herstein, Jews such as Abraham Newman, a 52-year-old, Prussian-born dry goods merchant, and Bernard Wise, another German-born dry goods merchant, 64-years-old, were present.

The new congregation immediately defined its terms of existence and religious preferences in their constitution. Like most other Southern congregations, B’nai Shalom adhered to the Reform Judaism of Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise in Cincinnati. As such, Wise’s prayer book, Minhag America, served as a basis for the new congregation’s services.

As evidenced by the constitution, the members of B’nai Sholom placed special emphasis on the strict maintenance of decorum, both in temple administrative business and prayer services. First, the constitution provided for the warning that “any member marrying out of the pale of the Jewish religion forfeits his membership.” The constitution also dealt sternly with more mundane ordinances, such as that everyone must “conform strictly” to the regulations respecting the time when the congregation was standing or sitting. Another provision cites the unannounced withdrawal from a congregation meeting as grounds for a one dollar fine. Such stipulations suggest that the founding members were deeply concerned with the coherence and stability of the nascent congregation.

In its early years, money was often an issue for the congregation. They struggled to furnish their rented room in time for the High Holidays in 1876. Members who fell behind on their dues were suspended and their names published in the nationally circulated American Israelite newspaper. Of their 32 founding members in 1876, only 15 were still contributing members by 1878; 11 had been suspended for failure to pay dues. The Ladies Hebrew Charity Society supported the congregation, holding a charity ball that raised money to refurbish their meeting room in 1885.

Despite these financial woes, B’nai Sholom worked to establish itself as the centerpiece of a burgeoning community. In 1877, the board approved a motion to join the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, although it left two years later because of the financial burden of membership; over its early years, B’nai Sholom would join and then leave the UAHC several times due to financial concerns. For over 11 years, Abe Newman, a Bavarian-born merchant, led services and oversaw the religious school. When Newman died in 1890, the congregation decided to seek its first full-time rabbi. After a few years of hosting student rabbis, the congregation hired Rabbi A.M Bloch of Port Gibson, Mississippi in November of 1892. His tenure lasted less than a year due to congregants’ disapproval of his sermons, which they found to be “distasteful to the entire membership of the congregation.” Apparently, Bloch was very critical of members who did not attend services, and singled them out personally during his sermons. He was replaced by a unanimous decision of the board by Rabbi I.E. Wagenheim, the first in a line of seven rabbis who served the congregation from one to three years.

Many lay leaders had been involved in leadership positions at B’nai Sholom in its early history, especially before the search for a full-time rabbi began in 1890. However, in a truly unusual move to fill a pulpit vacancy created by an ill rabbi in 1905, a local Episcopal minister, Rev. Claybrook, volunteered his services for Friday night services, which the Temple board accepted. This incident reveals how integrated B’nai Sholom was in the city’s religious life, and how Reform their services were. A Christian minister would only be able to lead services if they were largely in English rather than Hebrew.

After almost two decades, the Huntsville Jewish community finally decided it needed its own house of worship. The board minutes from June 16th, 1898, mark the first mention of building a temple for B’nai Sholom, with Ike Schiffman advocating on its behalf. The motion was carried unanimously, and the board began to put the organizing committees in place. In May of 1898, the congregation purchased land at the corner of Lincoln and Clinton streets for $1500. When the building was still in construction during that year’s High Holidays, a local Baptist church offered its space for services.The dedication of the B’nai Israel’s synagogue was held on November 26, 1898, and was, by all accounts a festive and impressive occasion. At the time, Ike Schiffman was President and Nathan Michnic was rabbi. The Huntsville Weekly Democrat used the dedication to reflect on the Jewish presence in Huntsville: “The erection of this temple gives us food for thought regarding the industry of the people who build it,” the paper wrote. “The Jews of Huntsville are examples of industry and thrift…There are Jewish merchants who came to this town with little more than their clothes…and have become the leading merchants and desirable citizens.” The article went on to laud Huntsville’s Jews for their social circles, charity work, and their venerable insistence on a good education for their children, concluding that “once cannot help but admire a people who through industry have achieved such results in a few years.”

Despite their new synagogue, the congregation continued to have problems hiring and retaining rabbis in the early-twentieth century. In 1907, when their rabbi demanded a raise, the congregation, which only had 38 members, asked him to resign. Informed by the UAHC that there were no Reform rabbis willing to take the pulpit in Huntsville, the board wrote to Solomon Schechter, president of the Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, to see if they had any candidates. At the time, B’nai Sholom was classically Reform, with Shabbat services on Friday nights only and primarily English language prayers. A JTS graduate was unlikely to accept such a position, and nothing came of this effort. Their frustration over the inability to hire a rabbi led the congregation to drop its membership in the Reform UAHC in 1910.

Despite their new synagogue, the congregation continued to have problems hiring and retaining rabbis in the early-twentieth century. In 1907, when their rabbi demanded a raise, the congregation, which only had 38 members, asked him to resign. Informed by the UAHC that there were no Reform rabbis willing to take the pulpit in Huntsville, the board wrote to Solomon Schechter, president of the Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, to see if they had any candidates. At the time, B’nai Sholom was classically Reform, with Shabbat services on Friday nights only and primarily English language prayers. A JTS graduate was unlikely to accept such a position, and nothing came of this effort. Their frustration over the inability to hire a rabbi led the congregation to drop its membership in the Reform UAHC in 1910.

An Early-Twentieth-Century Decline and a Mid-Twentieth-Century Boom

While Huntsville’s Jewish merchant class had achieved respect for their establishments, the Jewish population of the city remained relatively stagnant and small. In 1880, B’nai Sholom had 23 families. While the congregation peaked in 1907 with 38 families, it had dropped back down to 23 families by 1940. This includes the small number of Jews B’nai Sholom attracted in the 1930s from the nearby towns of Athens and Decatur. Both of these towns had short-lived Jewish congregations in the 1910s, but by 1930, Decatur and Athens Jews had joined B’nai Sholom. In 1878, the total Jewish population of Huntsville was about 72 people; 60 years later, the community had grown only slightly, to 100 individuals. The Great Depression of the 1930s had left the town’s industrial core in decline, and was a time a financial retrenchment for B’nai Sholom. In 1931, the board reduced each member’s dues and voted not to hire a visiting rabbi for the High Holidays. Indeed, B’nai Sholom had not been able to support a full-time rabbi since 1913.

The watershed moment in Huntsville history came at the onset of World War II. In 1940, Huntsville was chosen as the location for Redstone arsenal, a massive military installation. Nine years later, with the lobbying of Alabama Senator John Sparkman and Major General Holger Toftoy, the arsenal became the base for a new missile research program. In 1950, German rocket scientist Werner Von Braun was recruited to lead the efforts at the base. This program would soon evolve into the Marshall Space Flight Center within the Redstone Arsenal, dedicated by President Eisenhower in 1960. To this day, the center is a hub of development for new missiles and the space shuttle program. Von Braun, who achieved a national celebrity status for his work in creating rocket technology, particularly the Saturn V rocket, would call Huntsville home for 20 years.

This dramatic shift in Huntsville’s economy heralded the rapid influx of Jewish scientists, engineers, and other professionals by the 1950s and 1960s. The city as a whole grew enormously, from 13,100 people in 1940, to 137,800 in 1970. A Jewish population of 100 in 1937 ballooned to 700 people by 1968. A congregation that had counted 16 contributing households as late as 1945 had 102 by 1970. This demographic explosion is clearly reflected in B’nai Sholom’s history. The congregation made a special effort to reach out to these new residents, sending letters to each Jewish serviceman working at the arsenal in 1951 inviting them to attend High Holiday services at B’nai Sholom. By 1963, the congregation was able to hire its first full-time rabbi in fifty years; it has not been without full-time rabbinic leadership ever since. Requiring expansion, B’nai Sholom bought an adjacent building, the Carlisle Davis house, in 1956. The Davis building, next to the original synagogue, was demolished and rebuilt as an education annex in 1967. By the 1960s, the congregation had grown so much that High Holiday services had to be held at the post chapel in Redstone Arsenal.

A New Congregation

The growth of the Huntsville Jewish community in the mid-twentieth century also gave rise to the establishment of a Conservative Jewish congregation, Etz Chayim, founded in 1962. Though its first president, Harold Pizitz, was a native Huntsvillian, most members of Etz Chayim came from other parts of the country and were not comfortable with the classical Reform worship style at B’nai Sholom. The new congregation affiliated with the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism. Etz Chayim’s nine founding members originally met in a classroom of a local private school, and later rented several other spaces as meeting places for the congregation. In 1969, Etz Chayim bought a small former church on Bailey Cove Road which they dedicated as their synagogue. The congregation has never had a full-time rabbi; over the years, they have used lay leaders and student rabbis from the Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary, as well as retired visiting rabbis. As of 2008, Etz Chayim had 55 member families, most of whom work for NASA, the military, or related contractors. In recent years, Etz Chayim has formed a joint religious school with B’nai Sholom, using the education curriculum of the Institute of Southern Jewish Life.

While Huntsville’s Jewish merchant class had achieved respect for their establishments, the Jewish population of the city remained relatively stagnant and small. In 1880, B’nai Sholom had 23 families. While the congregation peaked in 1907 with 38 families, it had dropped back down to 23 families by 1940. This includes the small number of Jews B’nai Sholom attracted in the 1930s from the nearby towns of Athens and Decatur. Both of these towns had short-lived Jewish congregations in the 1910s, but by 1930, Decatur and Athens Jews had joined B’nai Sholom. In 1878, the total Jewish population of Huntsville was about 72 people; 60 years later, the community had grown only slightly, to 100 individuals. The Great Depression of the 1930s had left the town’s industrial core in decline, and was a time a financial retrenchment for B’nai Sholom. In 1931, the board reduced each member’s dues and voted not to hire a visiting rabbi for the High Holidays. Indeed, B’nai Sholom had not been able to support a full-time rabbi since 1913.

The watershed moment in Huntsville history came at the onset of World War II. In 1940, Huntsville was chosen as the location for Redstone arsenal, a massive military installation. Nine years later, with the lobbying of Alabama Senator John Sparkman and Major General Holger Toftoy, the arsenal became the base for a new missile research program. In 1950, German rocket scientist Werner Von Braun was recruited to lead the efforts at the base. This program would soon evolve into the Marshall Space Flight Center within the Redstone Arsenal, dedicated by President Eisenhower in 1960. To this day, the center is a hub of development for new missiles and the space shuttle program. Von Braun, who achieved a national celebrity status for his work in creating rocket technology, particularly the Saturn V rocket, would call Huntsville home for 20 years.

This dramatic shift in Huntsville’s economy heralded the rapid influx of Jewish scientists, engineers, and other professionals by the 1950s and 1960s. The city as a whole grew enormously, from 13,100 people in 1940, to 137,800 in 1970. A Jewish population of 100 in 1937 ballooned to 700 people by 1968. A congregation that had counted 16 contributing households as late as 1945 had 102 by 1970. This demographic explosion is clearly reflected in B’nai Sholom’s history. The congregation made a special effort to reach out to these new residents, sending letters to each Jewish serviceman working at the arsenal in 1951 inviting them to attend High Holiday services at B’nai Sholom. By 1963, the congregation was able to hire its first full-time rabbi in fifty years; it has not been without full-time rabbinic leadership ever since. Requiring expansion, B’nai Sholom bought an adjacent building, the Carlisle Davis house, in 1956. The Davis building, next to the original synagogue, was demolished and rebuilt as an education annex in 1967. By the 1960s, the congregation had grown so much that High Holiday services had to be held at the post chapel in Redstone Arsenal.

A New Congregation

The growth of the Huntsville Jewish community in the mid-twentieth century also gave rise to the establishment of a Conservative Jewish congregation, Etz Chayim, founded in 1962. Though its first president, Harold Pizitz, was a native Huntsvillian, most members of Etz Chayim came from other parts of the country and were not comfortable with the classical Reform worship style at B’nai Sholom. The new congregation affiliated with the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism. Etz Chayim’s nine founding members originally met in a classroom of a local private school, and later rented several other spaces as meeting places for the congregation. In 1969, Etz Chayim bought a small former church on Bailey Cove Road which they dedicated as their synagogue. The congregation has never had a full-time rabbi; over the years, they have used lay leaders and student rabbis from the Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary, as well as retired visiting rabbis. As of 2008, Etz Chayim had 55 member families, most of whom work for NASA, the military, or related contractors. In recent years, Etz Chayim has formed a joint religious school with B’nai Sholom, using the education curriculum of the Institute of Southern Jewish Life.

The Jewish Community in Huntsville Today

Beyond the statistical measures of recent success in Huntsville, there remain physical reminders of a past very much rooted in the Jewish merchant class. Several stately historic buildings once owned by Jews still grace downtown Huntsville, including the Bernstein house and the I. Schiffman building. The latter, built around 1845, was bought by Isaac Schiffman in 1905, and his name remains engraved on its exterior. Two years earlier, famed stage actress Tallulah Bankhead was born in its third floor apartment. A businessman first in dry goods and then later moving into investments, Schiffman ensured that the following four generations of the Schiffman and Goldsmith families have retained control of the building, continuing today with Margaret Ann Goldsmith, a direct descendant of these early Huntsville Jewish families. With her office in the Schiffman building, she continues her work as a historian and philanthropist to preserve the heritage and history of Jews in “Rocket City.”

With two congregations and a Jewish Federation, the Huntsville Jewish Community continues to flourish with around 750 Jews. While the Jewish communities of nearby Athens and Decatur have long since disappeared, the science and technology-oriented economy, along with perennial acclaim for its quality of life, have made Huntsville a thriving regional center of Jewish life.

With two congregations and a Jewish Federation, the Huntsville Jewish Community continues to flourish with around 750 Jews. While the Jewish communities of nearby Athens and Decatur have long since disappeared, the science and technology-oriented economy, along with perennial acclaim for its quality of life, have made Huntsville a thriving regional center of Jewish life.