Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Selma, Alabama

Historical Overview

|

Located near the center of the state on the Alabama River, the town of Selma sits in the crux of the “black belt” region of Alabama, a nickname derived both from the region’s historically rich, black cotton soil and its relatively dense African American population. Though the popular historical imagination regards Selma as synonymous with the American Civil Rights Struggle of the 1950s and 1960s, particularly the watershed 1965 voting rights march from Selma to Montgomery, the seat of Dallas County has a history dating back to the 18th century. The site first came under French control in 1732 as the settlement of “Ecor Bienville.” Selma was incorporated in its present name in 1820. In the same year, the nearby town of Cahawba was chosen as the first permanent capital of Alabama, also serving as the Dallas county seat until 1866, when it was moved back to Selma. Jews arrived in Selma in the 1830s and played an important part in the city's history.

|

RESOURCES

Jewish Cemetery List |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Selma

Early Settlers

Jews first came to Selma in the 1830s from downriver in Mobile. These itinerant merchants were of Sephardic ancestry, who had emigrated to the West Indies and eventually to seaports like Charleston, South Carolina, Mobile, and New Orleans. Some had further moved upriver to Selma, constituting the town’s first, if ephemeral, Jewish presence. Around 1840, Ashkenazi Jews from Western Europe, mainly Germany, began arriving in Selma, immigrating mainly to escape conscription by the German army or for economic reasons. A third wave of immigration came in the 1880s, when Eastern European Jews entered America through the northeast and then moved southward. In contrast to the predilection of German Jews for grand retail businesses and banking, these later immigrants opened less expensive general merchandise and wholesale stores.

The Civil War

During the American Civil War, Selma functioned as a manufacturing center for the Confederacy, producing supplies and munitions. The town’s central location, railroad connections, and existing manufacturing infrastructure proved vital to war efforts until a Union army overran General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s defense of the town in the Battle of Selma in April of 1865. The conflict sometimes split Selma’s Jewish families. Throughout the war, Selma merchant Joseph Seligman, at the request of President Abraham Lincoln, raised money for the Union war effort in England, while the other Seligman brothers fought for the Confederacy.

Jews first came to Selma in the 1830s from downriver in Mobile. These itinerant merchants were of Sephardic ancestry, who had emigrated to the West Indies and eventually to seaports like Charleston, South Carolina, Mobile, and New Orleans. Some had further moved upriver to Selma, constituting the town’s first, if ephemeral, Jewish presence. Around 1840, Ashkenazi Jews from Western Europe, mainly Germany, began arriving in Selma, immigrating mainly to escape conscription by the German army or for economic reasons. A third wave of immigration came in the 1880s, when Eastern European Jews entered America through the northeast and then moved southward. In contrast to the predilection of German Jews for grand retail businesses and banking, these later immigrants opened less expensive general merchandise and wholesale stores.

The Civil War

During the American Civil War, Selma functioned as a manufacturing center for the Confederacy, producing supplies and munitions. The town’s central location, railroad connections, and existing manufacturing infrastructure proved vital to war efforts until a Union army overran General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s defense of the town in the Battle of Selma in April of 1865. The conflict sometimes split Selma’s Jewish families. Throughout the war, Selma merchant Joseph Seligman, at the request of President Abraham Lincoln, raised money for the Union war effort in England, while the other Seligman brothers fought for the Confederacy.

Organized Jewish Life in Selma

Selma Jews established Congregation Mishkan Israel in 1870, although they had formed a predecessor group three years earlier. They conducted services at private residences. Soon after its founding, Mishkan Israel affiliated with the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, the national organization of Reform Judaism. In 1876, the congregation began to rent an Episcopal church for its functions, and sixteen years later, they acquired a parsonage and school house on Broad Street for Sunday school. The congregation quickly decided to build a permanent temple on that site. Ground was broken in June of 1899, and the building was completed in December of that year. Finally, in February 1900, the synagogue was dedicated.

In the congregation’s early decades, although their membership was relatively small, Mishkan Israel was able to support a full-time rabbi. From 1885 through 1976, Mishkan Israel usually employed a rabbi, although its small size meant that most of their spiritual leaders did not stay in Selma for very long. From 1910 to 1930, the congregation reached a plateau of 80 members. Its membership peaked at 104 households in 1940. Since then, its membership has gradually declined. The congregation’s last full-time rabbi, Lothair Lubasch, died in 1976. In the early 20th century an Orthodox congregation, B'nai Abraham, located at the corner of Alabama and Green, was founded, but eventually disbanded due to declining membership in 1944. Its remaining members joined Mishkan Israel.

The same year that Selma Jews organized for communal prayer, they also established a Jewish social club. Founded in 1867, the Harmony Club erected a three-story brick building on Water Avenue in 1909. This edifice served as a social hub for the Jewish community, hosting dances, card games, billiards and other social functions. Non-Jews would occasionally rent out the space to host their events. In 1999, the abandoned building, which had become an Elks Club in the 1930s, was bought and renovated by a private owner and is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Selma Jews established Congregation Mishkan Israel in 1870, although they had formed a predecessor group three years earlier. They conducted services at private residences. Soon after its founding, Mishkan Israel affiliated with the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, the national organization of Reform Judaism. In 1876, the congregation began to rent an Episcopal church for its functions, and sixteen years later, they acquired a parsonage and school house on Broad Street for Sunday school. The congregation quickly decided to build a permanent temple on that site. Ground was broken in June of 1899, and the building was completed in December of that year. Finally, in February 1900, the synagogue was dedicated.

In the congregation’s early decades, although their membership was relatively small, Mishkan Israel was able to support a full-time rabbi. From 1885 through 1976, Mishkan Israel usually employed a rabbi, although its small size meant that most of their spiritual leaders did not stay in Selma for very long. From 1910 to 1930, the congregation reached a plateau of 80 members. Its membership peaked at 104 households in 1940. Since then, its membership has gradually declined. The congregation’s last full-time rabbi, Lothair Lubasch, died in 1976. In the early 20th century an Orthodox congregation, B'nai Abraham, located at the corner of Alabama and Green, was founded, but eventually disbanded due to declining membership in 1944. Its remaining members joined Mishkan Israel.

The same year that Selma Jews organized for communal prayer, they also established a Jewish social club. Founded in 1867, the Harmony Club erected a three-story brick building on Water Avenue in 1909. This edifice served as a social hub for the Jewish community, hosting dances, card games, billiards and other social functions. Non-Jews would occasionally rent out the space to host their events. In 1999, the abandoned building, which had become an Elks Club in the 1930s, was bought and renovated by a private owner and is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Jewish Businesses in Selma

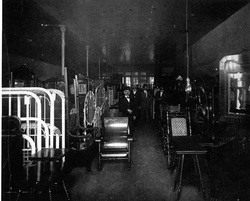

As Mishkan Israel began to develop in the late 19th century, Jewish merchants dominated downtown Selma. Broad Street was lined by stores with names like Tepper’s, Kayser’s Liepold’s, Rothchild’s and others. In addition to these enterprises there was a surprising variety of specialty retailers. The L.C. Adler furniture company, the Siegel Automobile Company, Benish and Meyer Tobacco, and Richard Thalheimer liquors reveal just some of the diversity of Jewish enterprise in Selma. Different streets had stores with different specialties. Broad Street contained most of the large department stores like Tepper’s and Kayser's, while Water Avenue was home to the wholesalers and cotton merchants, and Alabama Avenue was lined with stores with less expensive merchandise such as Barton’s, Bendersky’s and Eagle’s.

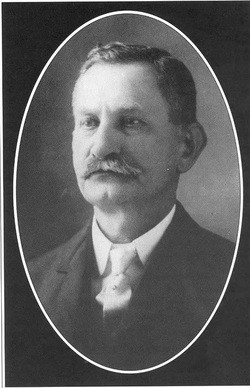

Morris Hohenberg's cotton business, which he established in 1879 and ran with his sons, was particularly dominant in its area. His obituary in the Selma Times-Journal in January 1928 describes his vast personal and business influence. Known for his charismatic personality, Hohenberg had held leadership positions at Temple Mishkan Israel in Selma, was a Mason and Shriner, help found the state agricultural school in Wetumpka, and served on the board of directors at the First National Bank of Wetumpka. “In business, civic and social circles throughout Alabama and the south, Mr. Hohenberg was known as a leader and his circle of friends extends far past the boundaries of the state,” the paper wrote.

Benjamin Schuster, one of the most prominent hardware merchants in Selma by 1900, served as the first president of the Harmony Club, holding the position for 30 years. He was also very active in the city’s political and religious life, serving as a trustee of Mishkan Israel, president of Selma’s Kiwanis Club, jury commissioner for Dallas County, and a member of Alabama Governor Edward A. O’Neal’s staff. Schuster’s son-in-law, Walter L. Bloch, continued this legacy as a leading Selma citizen. Like Schuster, Bloch worked as a hardware merchant by day, but also dedicated much time to the city’s civic, social, and religious organizations, serving as president of Mishkan Israel, president of the Selma Chamber of Commerce, and a member of the Selma School Board. When Bloch died in 1933, many stores throughout Selma closed at the hour of his funeral, recognizing his significant contribution to the city.

As Mishkan Israel began to develop in the late 19th century, Jewish merchants dominated downtown Selma. Broad Street was lined by stores with names like Tepper’s, Kayser’s Liepold’s, Rothchild’s and others. In addition to these enterprises there was a surprising variety of specialty retailers. The L.C. Adler furniture company, the Siegel Automobile Company, Benish and Meyer Tobacco, and Richard Thalheimer liquors reveal just some of the diversity of Jewish enterprise in Selma. Different streets had stores with different specialties. Broad Street contained most of the large department stores like Tepper’s and Kayser's, while Water Avenue was home to the wholesalers and cotton merchants, and Alabama Avenue was lined with stores with less expensive merchandise such as Barton’s, Bendersky’s and Eagle’s.

Morris Hohenberg's cotton business, which he established in 1879 and ran with his sons, was particularly dominant in its area. His obituary in the Selma Times-Journal in January 1928 describes his vast personal and business influence. Known for his charismatic personality, Hohenberg had held leadership positions at Temple Mishkan Israel in Selma, was a Mason and Shriner, help found the state agricultural school in Wetumpka, and served on the board of directors at the First National Bank of Wetumpka. “In business, civic and social circles throughout Alabama and the south, Mr. Hohenberg was known as a leader and his circle of friends extends far past the boundaries of the state,” the paper wrote.

Benjamin Schuster, one of the most prominent hardware merchants in Selma by 1900, served as the first president of the Harmony Club, holding the position for 30 years. He was also very active in the city’s political and religious life, serving as a trustee of Mishkan Israel, president of Selma’s Kiwanis Club, jury commissioner for Dallas County, and a member of Alabama Governor Edward A. O’Neal’s staff. Schuster’s son-in-law, Walter L. Bloch, continued this legacy as a leading Selma citizen. Like Schuster, Bloch worked as a hardware merchant by day, but also dedicated much time to the city’s civic, social, and religious organizations, serving as president of Mishkan Israel, president of the Selma Chamber of Commerce, and a member of the Selma School Board. When Bloch died in 1933, many stores throughout Selma closed at the hour of his funeral, recognizing his significant contribution to the city.

Civic Engagement

At the same time that Jews encountered success in the business world, many became civically involved in Selma. In the late 1800s and early 20th century, Jews populated municipal positions like City Attorney, Water Commissioner, the Selma City Council, and the Selma School Board. Selma has seen three Jewish mayors: Simon Maas from 1887 to 1889, Marcus J. Meyer from 1895 to 1899, and Louis Benish, from 1915 to 1920. Born in Bavaria in 1845, Simon Maas was a dry goods retailer, while Marcus Meyer was also a German immigrant and owned the M.J. Meyer Stable and Harness Company on Water Avenue. Unlike the other two, Louis Benish, who owned Benish and Meyer Tobacco, was a native-born Alabaman.

The Selma Jewish community has also supplied two major political figures in the twentieth century. Democratic Congressman William Lehman represented the 13th and 17th districts of Florida from 1973 until 1993 before retiring. He died in 2005, but many buildings and institutions in South Florida bear his name. Marx Leva began his career as counsel to the fiscal director of the U.S. Navy in 1946, quickly moving on to become the General Counsel to the Secretary of Defense from 1947-49 and Assistant Secretary of Defense from 1949-51. In this position, Leva helped merge the Navy and War Department to create the new, unified Department of Defense. After retiring in 1951, he practiced law in Washington for almost 50 years. Both men were born and raised in Selma before attending the University of Alabama as undergraduates.

At the same time that Jews encountered success in the business world, many became civically involved in Selma. In the late 1800s and early 20th century, Jews populated municipal positions like City Attorney, Water Commissioner, the Selma City Council, and the Selma School Board. Selma has seen three Jewish mayors: Simon Maas from 1887 to 1889, Marcus J. Meyer from 1895 to 1899, and Louis Benish, from 1915 to 1920. Born in Bavaria in 1845, Simon Maas was a dry goods retailer, while Marcus Meyer was also a German immigrant and owned the M.J. Meyer Stable and Harness Company on Water Avenue. Unlike the other two, Louis Benish, who owned Benish and Meyer Tobacco, was a native-born Alabaman.

The Selma Jewish community has also supplied two major political figures in the twentieth century. Democratic Congressman William Lehman represented the 13th and 17th districts of Florida from 1973 until 1993 before retiring. He died in 2005, but many buildings and institutions in South Florida bear his name. Marx Leva began his career as counsel to the fiscal director of the U.S. Navy in 1946, quickly moving on to become the General Counsel to the Secretary of Defense from 1947-49 and Assistant Secretary of Defense from 1949-51. In this position, Leva helped merge the Navy and War Department to create the new, unified Department of Defense. After retiring in 1951, he practiced law in Washington for almost 50 years. Both men were born and raised in Selma before attending the University of Alabama as undergraduates.

The Civil Rights Movement

Like other southern Jewish communities, most of Selma’s Jews maintained a complex relationship with both the segregationist and integrationist camps during the civil rights movement. In January of 1956, members of the Selma B'nai Brith lodge issued a declaration urging groups like the American Defamation League and American Jewish Committee to avoid intervening in affairs outside of the Jewish community, particularly on the issue of civil rights. This statement represented a broader antipathy of southern Jewry against northern-dominated Jewish groups’ intervention in their affairs. Yet, sociologist Marshall Bloom estimated that less than a fifth of Mishkan Israel’s congregants during the era could be described as segregationists.

As individuals, Selma’s Jews held a wide range of stances towards the civil rights movement, from opposition to tacit accommodation to outright activism. Sol Tepper, a member of the Selma Jewish community, was an ardent segregationist. A member of Mishkan Israel and a WWII veteran, Tepper was a vocal foe of integration efforts in Alabama. His role as a spokesman for the segregationists transcended the boundaries of the Selma Jewish community as he wrote dozens of editorials for the Selma Times-Journal. When Martin Luther King arrived in January 1965 for his now historic voter registration campaign, Tepper, as part of the County sheriff’s posse, helped make many arrests of activists. His zealotry against civil rights workers was so intense that the sheriff’s deputy remembers having to restrain Tepper from handling his M-1 rifle at a demonstration. From the first inklings of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s to the aftermath of “Bloody Sunday” in 1965, Tepper unwaveringly represented white resistance in Selma, even as he did not represent the views of most Selma Jews.

Like other southern Jewish communities, most of Selma’s Jews maintained a complex relationship with both the segregationist and integrationist camps during the civil rights movement. In January of 1956, members of the Selma B'nai Brith lodge issued a declaration urging groups like the American Defamation League and American Jewish Committee to avoid intervening in affairs outside of the Jewish community, particularly on the issue of civil rights. This statement represented a broader antipathy of southern Jewry against northern-dominated Jewish groups’ intervention in their affairs. Yet, sociologist Marshall Bloom estimated that less than a fifth of Mishkan Israel’s congregants during the era could be described as segregationists.

As individuals, Selma’s Jews held a wide range of stances towards the civil rights movement, from opposition to tacit accommodation to outright activism. Sol Tepper, a member of the Selma Jewish community, was an ardent segregationist. A member of Mishkan Israel and a WWII veteran, Tepper was a vocal foe of integration efforts in Alabama. His role as a spokesman for the segregationists transcended the boundaries of the Selma Jewish community as he wrote dozens of editorials for the Selma Times-Journal. When Martin Luther King arrived in January 1965 for his now historic voter registration campaign, Tepper, as part of the County sheriff’s posse, helped make many arrests of activists. His zealotry against civil rights workers was so intense that the sheriff’s deputy remembers having to restrain Tepper from handling his M-1 rifle at a demonstration. From the first inklings of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s to the aftermath of “Bloody Sunday” in 1965, Tepper unwaveringly represented white resistance in Selma, even as he did not represent the views of most Selma Jews.

The Community Declines

The Selma Jewish community crested at around 325 Jews in 1937 and declined following World War II. The decrease was gradual at first, with Selma still having approximately 200 Jews in 1980. Over the last few decades, the drop has been precipitous, as today only about 20 Jews still remain in Selma, most all of whom are elderly. Yet even as the average age of Mishkan Israel’s dwindling membership rose to the 70s in the 1990s, there were glimmers of hope for the preservation of Selma’s Jewish heritage. Nashville residents Lynn and David Barton, whose families had owned Barton’s department store on Washington Street and Kayser's on Broad Street, reunited almost 300 Jews with Selma ties for Rosh Hashanah services in 1997 and 1999. The existing Selma Jews welcomed them back with festivities including an address by the mayor, tours of Selma sponsored by a local Methodist Church, and various family reunions.

The Selma Jewish community crested at around 325 Jews in 1937 and declined following World War II. The decrease was gradual at first, with Selma still having approximately 200 Jews in 1980. Over the last few decades, the drop has been precipitous, as today only about 20 Jews still remain in Selma, most all of whom are elderly. Yet even as the average age of Mishkan Israel’s dwindling membership rose to the 70s in the 1990s, there were glimmers of hope for the preservation of Selma’s Jewish heritage. Nashville residents Lynn and David Barton, whose families had owned Barton’s department store on Washington Street and Kayser's on Broad Street, reunited almost 300 Jews with Selma ties for Rosh Hashanah services in 1997 and 1999. The existing Selma Jews welcomed them back with festivities including an address by the mayor, tours of Selma sponsored by a local Methodist Church, and various family reunions.

The Jewish Community in Selma Today

While today the physical reminders of a once-burgeoning Jewish community in Selma, such as Temple Mishkan Israel and the Harmony Club, remain, a vital congregation does not. The congregation has not had a full-time rabbi for over 30 years, and only holds worship services a few times a year. Yet those like the Barton family and the remaining Jews are determined to preserve the rich history and heritage of Selma Jewry. In recent years, an effort has been made to raise money to restore Mishkan’s Israel historic synagogue and turn the space into a museum and community meeting space. In June, 2019, members of the congregation launched a crowdfunding campaign to collect donations toward that end.