Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Sand Mountain, Alabama

Historical Overview

Sand Mountain is a large plateau in northeastern Alabama that marks the southern tip of the Appalachian Range. It housed a Jewish collective community from 1904 to 1906.

The Story of the Jewish Community in Sand Mountain

The Nat settlement was atop the distant ridge.

The Nat settlement was atop the distant ridge. Photo by Jason Shelton.

After the fog had lifted from the valleys and canyons of Sand Mountain, Jacob Daneman might have had the pleasure of a spectacular view during his daily chores. This might be a small moment of enjoyment for Daneman, who would have to continue to work his fields for the survival of his community. Daneman was one of the original members of the collective community on the cliffs of Nat Mountain in Alabama. Arriving in Nat in 1904, he and his colleagues, primarily newly-emigrated Russian Jews, spent the next two years unsuccessfully trying to support themselves partly through manufacturing and by working the rugged land.

The Nat Mountain community was one of many Jewish settlements in America that hoped to become a self-sufficient community. Many Jewish organizations saw the formation of rural, agricultural, communes as a way to provide for the influx of Eastern European Jews into the United States. At a national meeting of B’nai B’rith in 1855, Dr. Sigmund Waterman presented a paper entitled “A Call to Establish a Hebrew Agricultural Society.” Waterman argued that there was a false global impression that Jews were uninterested in agriculture and unable to succeed in manual work. He saw the establishment of farming communes as a way to battle international anti-Semitism; by getting Jews out of urban settings and their traditional roles as business middlemen, they could present the world with a more favorable image of Jews.

During the wave of Jewish immigration to the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many American Jews saw agricultural communities as a good outlet for these newcomers. Jewish farming communes formed around the country, from South Dakota, to Ohio, to New Jersey. Some were socialist in ideology, while others were more religious. Among the first was a community in Sicily Island, Louisiana. Moses Herder and Manya Bakal started an organization called Am Olam (Eternal People), which hoped to connect Jews with the moral purity of labor. Am Olam started 24 settlements in the 1880s, including one in Newport, Arkansas. Usually, the results of their efforts were short-lived, and sometimes disastrous.

Perhaps inspired by these previous examples, or perhaps by socialist ideals, a group of Russian-Jewish immigrants in New York City formed the Mechanics Industrial Union, bought land in rural Alabama near the small town of Nat, and prepared to recruit subscribers. They planned to establish a sustainable collective farm and a shirtwaist factory where all of the community members would work for wages. The original Certificate of Incorporation, written on July 14, 1904, stated, “The corporation reserves the right to sell or transfer the common stock to able-bodied persons only,” and stipulated that buyers had to be between the ages of 21 and 40. The certificate never specified the gender of the buyers, however, and two women, Jennie Beck and Rose Kaplan, served among the initial shareholders. Beck also sat on the original Board of Directors of the corporation. Joseph Kaplan, whose family was also in charge of the shirtwaist factory, served as president of the corporation. Other board members included Morris Trupin, Joseph Kurlansky, Samuel Segal, Max Cohn, Samuel Youngerman, and the above-mentioned Jennie Beck. Also present at the first meeting of the Mechanics Industrial Union were Jacob Daneman, Jacob Weitzman, Rose Kaplan, Samuel Berman, and several others, including Charles Smurdinsky, Jacob Cohen, and board member Jacob Kurlansky, who signed the Certificate of Incorporation in Yiddish, presumably because they could not write in English. All lived in New York City in 1904 and none had agricultural experience.

The Nat Mountain community was one of many Jewish settlements in America that hoped to become a self-sufficient community. Many Jewish organizations saw the formation of rural, agricultural, communes as a way to provide for the influx of Eastern European Jews into the United States. At a national meeting of B’nai B’rith in 1855, Dr. Sigmund Waterman presented a paper entitled “A Call to Establish a Hebrew Agricultural Society.” Waterman argued that there was a false global impression that Jews were uninterested in agriculture and unable to succeed in manual work. He saw the establishment of farming communes as a way to battle international anti-Semitism; by getting Jews out of urban settings and their traditional roles as business middlemen, they could present the world with a more favorable image of Jews.

During the wave of Jewish immigration to the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many American Jews saw agricultural communities as a good outlet for these newcomers. Jewish farming communes formed around the country, from South Dakota, to Ohio, to New Jersey. Some were socialist in ideology, while others were more religious. Among the first was a community in Sicily Island, Louisiana. Moses Herder and Manya Bakal started an organization called Am Olam (Eternal People), which hoped to connect Jews with the moral purity of labor. Am Olam started 24 settlements in the 1880s, including one in Newport, Arkansas. Usually, the results of their efforts were short-lived, and sometimes disastrous.

Perhaps inspired by these previous examples, or perhaps by socialist ideals, a group of Russian-Jewish immigrants in New York City formed the Mechanics Industrial Union, bought land in rural Alabama near the small town of Nat, and prepared to recruit subscribers. They planned to establish a sustainable collective farm and a shirtwaist factory where all of the community members would work for wages. The original Certificate of Incorporation, written on July 14, 1904, stated, “The corporation reserves the right to sell or transfer the common stock to able-bodied persons only,” and stipulated that buyers had to be between the ages of 21 and 40. The certificate never specified the gender of the buyers, however, and two women, Jennie Beck and Rose Kaplan, served among the initial shareholders. Beck also sat on the original Board of Directors of the corporation. Joseph Kaplan, whose family was also in charge of the shirtwaist factory, served as president of the corporation. Other board members included Morris Trupin, Joseph Kurlansky, Samuel Segal, Max Cohn, Samuel Youngerman, and the above-mentioned Jennie Beck. Also present at the first meeting of the Mechanics Industrial Union were Jacob Daneman, Jacob Weitzman, Rose Kaplan, Samuel Berman, and several others, including Charles Smurdinsky, Jacob Cohen, and board member Jacob Kurlansky, who signed the Certificate of Incorporation in Yiddish, presumably because they could not write in English. All lived in New York City in 1904 and none had agricultural experience.

Rabbi Morris Newfield

Rabbi Morris Newfield

All of the work and 60% of the profits from the venture were to be shared equally among the community, while 40% would be set aside as a financial safety net for the entire corporation. Future boards would be elected democratically by shareholders. Unfortunately, not every community member came to Nat with a utopian vision or a desire for collectivist living. Twenty-three-year-old Morris Brandman came to New York in 1903. Almost immediately after stepping off the boat from his Atlantic crossing, Brandman met two men who said they could get him a good job at a shirt factory. Before he knew it, he was traveling to Alabama with the financial backing of these mysterious strangers. To his surprise, that shirt factory turned out to be the Nat community. After arriving, Brandman married Ida Daneman, sister of Jacob Daneman.

Most Jews had a less spontaneous route to Nat. The Industrial Removal Office (IRO) was a national organization that sought to resettle poor Jewish immigrants in New York to cities and towns around the country. The IRO had a local committee in Birmingham led by the Reform rabbi Morris Newfield, who took the Nat settlement under his wing. Rabbi Newfield wrote to David Bressler, the General Manager of the IRO, asking him to send a number of shirt makers to the colony, where they could find work. The Birmingham IRO committee raised money to help assist the colony as early as August, 1905. Committee member I.J. White wrote that month: “I have no doubt but if carried out carefully and on strict business basis that [the colony] will be a success.”

At the Nat settlement, which was located in Jackson County between the small towns of Woodville and Pleasant Groves, the community worked from the very first light to well after sundown. In the morning, they were responsible for working in the sweatshop-like conditions of the shirt factory, while afterward they had to tend to an entire farm. In addition to crops, they also raised geese, chickens, and hogs. On top of these time-consuming and often back-breaking tasks, there was a growing number of children to care for and raise.

Many of the Nat Jews became disillusioned because the settlement was so far away from rabbinical services and they missed the religious customs and traditions of their homelands. Even though the community was situated between the two Jewish populations of Birmingham, Alabama and Chattanooga, Tennessee, their location on top of a mountain made it impossible for Nat residents to make frequent trips to synagogue or have access to Jewish cemeteries. With no nearby mikvah or cemetery it was difficult to lead a traditional Jewish life. For life cycle events, Reverend Ephraim Mennen, an itinerant Rabbi, would come to Nat, but his journeys were long and difficult, often requiring him to leave in the middle of the night on a horse and buggy to travel up the steep and winding Appalachian roads.

The community constantly struggled with the economic realities of their mission. Keeping the shirt factory profitable proved extremely difficult. Providing food and maintaining a bare minimum standard of living for everyone meant working all the time, with little rest or time for religious practice. During one visit, Rev. Mennen once found a new mother scrubbing laundry. At the time, it was unthinkable for a woman to be out of bed so soon after giving birth, let alone engaging in manual labor.

Most Jews had a less spontaneous route to Nat. The Industrial Removal Office (IRO) was a national organization that sought to resettle poor Jewish immigrants in New York to cities and towns around the country. The IRO had a local committee in Birmingham led by the Reform rabbi Morris Newfield, who took the Nat settlement under his wing. Rabbi Newfield wrote to David Bressler, the General Manager of the IRO, asking him to send a number of shirt makers to the colony, where they could find work. The Birmingham IRO committee raised money to help assist the colony as early as August, 1905. Committee member I.J. White wrote that month: “I have no doubt but if carried out carefully and on strict business basis that [the colony] will be a success.”

At the Nat settlement, which was located in Jackson County between the small towns of Woodville and Pleasant Groves, the community worked from the very first light to well after sundown. In the morning, they were responsible for working in the sweatshop-like conditions of the shirt factory, while afterward they had to tend to an entire farm. In addition to crops, they also raised geese, chickens, and hogs. On top of these time-consuming and often back-breaking tasks, there was a growing number of children to care for and raise.

Many of the Nat Jews became disillusioned because the settlement was so far away from rabbinical services and they missed the religious customs and traditions of their homelands. Even though the community was situated between the two Jewish populations of Birmingham, Alabama and Chattanooga, Tennessee, their location on top of a mountain made it impossible for Nat residents to make frequent trips to synagogue or have access to Jewish cemeteries. With no nearby mikvah or cemetery it was difficult to lead a traditional Jewish life. For life cycle events, Reverend Ephraim Mennen, an itinerant Rabbi, would come to Nat, but his journeys were long and difficult, often requiring him to leave in the middle of the night on a horse and buggy to travel up the steep and winding Appalachian roads.

The community constantly struggled with the economic realities of their mission. Keeping the shirt factory profitable proved extremely difficult. Providing food and maintaining a bare minimum standard of living for everyone meant working all the time, with little rest or time for religious practice. During one visit, Rev. Mennen once found a new mother scrubbing laundry. At the time, it was unthinkable for a woman to be out of bed so soon after giving birth, let alone engaging in manual labor.

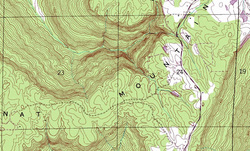

Topographic map of Nat Mountain.

Topographic map of Nat Mountain. Image courtesy of Jason Shelton.

The difficulties of life in the settlement led some families to leave. Joseph Bukofzer, a former colonist then living in Chattanooga, gave a negative report in the Jewish press, writing “it has been impossible for those who went there to make a living, and that almost all people who went there are now residing in [Chattanooga].” Rabbi Newfield rebutted these charges in a letter to the IRO leadership, claiming that all 40 people living in the colony had found work and in fact more settlers were needed. Newfield did admit that the “simple conditions of country life” dissatisfied some colonists who moved away, “prefer[ing] a larger city with its excitements to the simplicity and healthfulness of country life.” Additionally, according to Newfield, two families were forced to leave as they caused “contentions and strife among the others.”

Newfield praised the work of the colony, describing a sawmill where timber was cut and used for construction and of 25 acres of good land where vegetables and feed were grown. Newfield displayed his paternalistic feelings towards the Nat group, referring to it as “our Colony.” Indeed, the Birmingham Jewish community had invested $2,300 in the colony by 1906 and was in the process of raising an additional $1,500. However, despite their investment and Newfield’s hopes that Nat “may prove but a beginning of a larger number of similar Colonies built on the same place,” the colony, like those before it, failed.

Though the colonists worked tirelessly to survive, the infertile mountain soil destroyed any chance of a sustainable amateur farm. Because they ran out of food and money, the Mechanics Industrial Union voted to sell the land and the Nat commune dissolved in 1906. Dave Kopkin, nephew of Sam Kopkin, a founding member noted, "They tried to farm, [but] they just weren't farmers." The Kaplan family started a new shirt factory in Chattanooga and had more success in town, continuing business for many years. Jacob Daneman and his family also resettled in Chattanooga, along with many of the other families. Most eventually opened their own small businesses. The rest came down the mountain and scattered into Alabama, Tennessee, and Georgia. By 1908, there was little to no evidence of the community left on Nat Mountain.

Newfield praised the work of the colony, describing a sawmill where timber was cut and used for construction and of 25 acres of good land where vegetables and feed were grown. Newfield displayed his paternalistic feelings towards the Nat group, referring to it as “our Colony.” Indeed, the Birmingham Jewish community had invested $2,300 in the colony by 1906 and was in the process of raising an additional $1,500. However, despite their investment and Newfield’s hopes that Nat “may prove but a beginning of a larger number of similar Colonies built on the same place,” the colony, like those before it, failed.

Though the colonists worked tirelessly to survive, the infertile mountain soil destroyed any chance of a sustainable amateur farm. Because they ran out of food and money, the Mechanics Industrial Union voted to sell the land and the Nat commune dissolved in 1906. Dave Kopkin, nephew of Sam Kopkin, a founding member noted, "They tried to farm, [but] they just weren't farmers." The Kaplan family started a new shirt factory in Chattanooga and had more success in town, continuing business for many years. Jacob Daneman and his family also resettled in Chattanooga, along with many of the other families. Most eventually opened their own small businesses. The rest came down the mountain and scattered into Alabama, Tennessee, and Georgia. By 1908, there was little to no evidence of the community left on Nat Mountain.

Sources

Trivers, Trudy G. "Alabama's Sand Mountain an early kibbutz," in The Atlanta Jewish Times, April 24, 1987.