Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Florence/Sheffield, Alabama

Historical Overview

|

The Tri-Cities around Muscle Shoals in northwest Alabama have long attracted speculators taken with the economic potential of the area. When General Andrew Jackson passed through Muscle Shoals during the War of 1812 while trying to open a military road between Nashville to New Orleans, he was struck by its beauty and prime location on a plateau a hundred feet above the Tennessee River. A few years later, when his friend and colleague John Coffee became a partner in the Cypress Land Company that was developing the area, Jackson bought several plots of land, as did President James Monroe and former President James Madison. The city of Florence was incorporated in 1826 and quickly became a regional center for the cotton economy. For much of the nineteenth century, Florence remained a small agricultural town, as economic development was hindered by the Muscle Shoal, which made the Tennessee River unnavigable for large boats. A government-funded scheme to bypass the shoal with a canal in 1836 was unsuccessful and the area’s great potential remained untapped until the late 1880s, when Florence experienced an industrial boom.

Located close to raw materials like coal and limestone and sitting on the banks of the Tennessee River, Florence was a perfect exemplar of the “New South” boom in which sleepy farming towns were transformed into manufacturing centers. The city went from 1,500 people in 1886 to over 6,000 by 1890 as people came to work in the new iron and cotton mills that sprouted in Florence, Sheffield, and Tuscumbia. The Tri-Cities served as the nexus of the region’s cotton and iron economies, with ever growing railroad lines connecting the area to national commercial centers. Jewish settlement in the area preceded the industrial boom, although it remained quite limited until later in the nineteenth century. |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Florence/Sheffield

Early Settlers

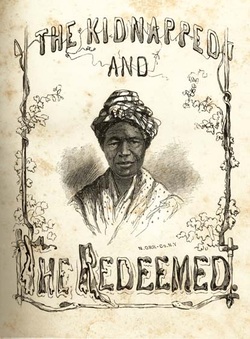

Brothers Joseph and Isaac Friedman were likely the first Jews to settle in the Shoals. They came down from Cincinnati to Tuscumbia in the mid 1840s and opened a dry goods store. The brothers didn’t stay long. Joseph headed out to California during the Gold Rush, and Isaac returned to Cincinnati in 1850. During their short time in Tuscumbia, however, they played an important role in helping a local slave named Peter Still gain his freedom. Still believed the brothers might be sympathetic to his desire to be free since, as recently arrived Jews, they were outsiders in the community. He convinced Isaac Friedman to purchase him for $500 and let him hire himself out to buy his freedom. Still was eventually able to purchase his freedom for $500, and Friedman personally escorted him to Cincinnati to ensure that Still was able to cross into free territory without being arrested as a fugitive slave. Still later published an account of his enslavement and emerged as an important voice for abolition.

While the Friedman brothers did not remain in Tuscumbia very long, Alexander Falk was among the first Jews to sink deep roots in the Tri-Cities. Born in Prussia in 1811, Falk left for England when he was only fourteen. He returned home nine years later. In 1841, he left Prussia once again, this time heading to New Orleans. After a few years in Vicksburg, where he met his wife Margaret, Falk moved to Florence and opened a dry goods store. His brother Louis owned a store in nearby Decatur. By 1860, Falk had become a successful merchant, owning $4,000 in real estate and over $20,000 in personal estate. The privations of the Civil War did not have much of an effect on Falk, who especially thrived during the early years of Reconstruction. When he died in 1871, the mayor and board of alderman passed a resolution honoring Falk as one of Florence’s “most promising and enterprising citizens.” Since there was no rabbi in the area, a local Baptist minister officiated at Falk’s funeral, using a Jewish prayer book he had found.

Brothers Joseph and Isaac Friedman were likely the first Jews to settle in the Shoals. They came down from Cincinnati to Tuscumbia in the mid 1840s and opened a dry goods store. The brothers didn’t stay long. Joseph headed out to California during the Gold Rush, and Isaac returned to Cincinnati in 1850. During their short time in Tuscumbia, however, they played an important role in helping a local slave named Peter Still gain his freedom. Still believed the brothers might be sympathetic to his desire to be free since, as recently arrived Jews, they were outsiders in the community. He convinced Isaac Friedman to purchase him for $500 and let him hire himself out to buy his freedom. Still was eventually able to purchase his freedom for $500, and Friedman personally escorted him to Cincinnati to ensure that Still was able to cross into free territory without being arrested as a fugitive slave. Still later published an account of his enslavement and emerged as an important voice for abolition.

While the Friedman brothers did not remain in Tuscumbia very long, Alexander Falk was among the first Jews to sink deep roots in the Tri-Cities. Born in Prussia in 1811, Falk left for England when he was only fourteen. He returned home nine years later. In 1841, he left Prussia once again, this time heading to New Orleans. After a few years in Vicksburg, where he met his wife Margaret, Falk moved to Florence and opened a dry goods store. His brother Louis owned a store in nearby Decatur. By 1860, Falk had become a successful merchant, owning $4,000 in real estate and over $20,000 in personal estate. The privations of the Civil War did not have much of an effect on Falk, who especially thrived during the early years of Reconstruction. When he died in 1871, the mayor and board of alderman passed a resolution honoring Falk as one of Florence’s “most promising and enterprising citizens.” Since there was no rabbi in the area, a local Baptist minister officiated at Falk’s funeral, using a Jewish prayer book he had found.

After the Civil War, growing numbers of Jews settled in the Shoals region. Abraham Bresler, a Prussian immigrant, settled in Tuscumbia in 1865. He initially owned a dry good business but had opened a grocery store by 1880. Many members of Bresler’s extended family eventually joined him in Tuscumbia.

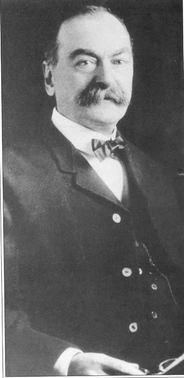

Perhaps the most notable Jewish settler in the area was Alfred Moses, who gambled his fortune building the new town of Sheffield, only to lose it all. Moses grew up in Charleston, South Carolina, before moving to Montgomery and starting a successful real estate and insurance business with his brother Mordecai. In 1883, Moses traveled to the Shoals area looking for potential sites for industrial development. In Florence, he was struck by the proximity of the Tennessee River and the abundance coal and iron ore in the area. He decided to build a new town on the south side of the river, naming it Sheffield, after England’s steel-making center. He formed the Sheffield Land, Iron & Coal Company with his brother Mordecai and raised money to build a railroad connecting the new town. By 1884, the Moses brothers were selling lots in this new town. They also built a steel-making blast furnace.

Alfred Moses moved to Sheffield in 1885 to supervise his many projects in the town, including the development of streets, water lines, and schools. The governor appointed Moses to be the town’s first mayor after Sheffield was incorporated in 1885. Sheffield’s industrial boom was short-lived due to overbuilding and a drop in iron prices. Moses had to close his blast furnace as the town went into economic decline. By 1893, Moses had moved to Louisville, Kentucky, and was practically destitute. While his dream of building an industrial city became an economic nightmare, Moses helped lay the foundation for Sheffield’s future development. After the turn of the century, Sheffield would emerge as an industrial center after the Birmingham Steel & Iron Company opened operations there.

Perhaps the most notable Jewish settler in the area was Alfred Moses, who gambled his fortune building the new town of Sheffield, only to lose it all. Moses grew up in Charleston, South Carolina, before moving to Montgomery and starting a successful real estate and insurance business with his brother Mordecai. In 1883, Moses traveled to the Shoals area looking for potential sites for industrial development. In Florence, he was struck by the proximity of the Tennessee River and the abundance coal and iron ore in the area. He decided to build a new town on the south side of the river, naming it Sheffield, after England’s steel-making center. He formed the Sheffield Land, Iron & Coal Company with his brother Mordecai and raised money to build a railroad connecting the new town. By 1884, the Moses brothers were selling lots in this new town. They also built a steel-making blast furnace.

Alfred Moses moved to Sheffield in 1885 to supervise his many projects in the town, including the development of streets, water lines, and schools. The governor appointed Moses to be the town’s first mayor after Sheffield was incorporated in 1885. Sheffield’s industrial boom was short-lived due to overbuilding and a drop in iron prices. Moses had to close his blast furnace as the town went into economic decline. By 1893, Moses had moved to Louisville, Kentucky, and was practically destitute. While his dream of building an industrial city became an economic nightmare, Moses helped lay the foundation for Sheffield’s future development. After the turn of the century, Sheffield would emerge as an industrial center after the Birmingham Steel & Iron Company opened operations there.

A Growing Community

In the late-nineteenth century, the Jewish population of the Shoals grew as the area attracted new industry and Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. Most owned stores in one of the Tri-Cities. In 1900, there were seven Jewish-owned stores in Florence, five in Sheffield, and two in Tuscumbia. One of these stores was owned by Morris Coplan, who left Russia in 1881, arriving in New York. After spending several years in Nashville, Coplan moved to Florence in 1887. He and his wife Lena had nine children. He opened a short-lived dry goods store before finding success with a grocery business. According to the local newspaper, Coplan did not limit himself to selling food but also dealt in furs, hides, beeswax, tallow, and “all kinds of junk.” Coplan became a respected local businessman, winning election to the Florence City Council in 1901. While his political opponent attempted to make an issue out of Coplan's Jewishness, Coplan defeated him and served several terms on the council. When he died suddenly in 1910, Rabbi Max Samfield of Memphis conducted the funeral.

Organized Jewish Life

Coplan’s Jewish funeral reflected Tri-City Jews' desire to maintain their religious traditions. As early as 1884, Florence Jews began to pray together, holding lay-led Rosh Hashanah services in the local Masonic Temple. Five years later, the Sheffield Land, Iron, and Coal Company—owned by the Moses brothers—deeded land to the town for a cemetery, including three acres that were specifically set aside for use as a Jewish burial ground. By the end of the 1890s, there was a growing number of Jewish children in the area, and parents organized a religious school with the assistance of Huntsville’s Rabbi Nathan Mitchnic. In 1900, Jews in the Tri-Cities began to discuss forming a congregation and building a synagogue. Calling themselves B’nai Israel (Children of Israel), the group began raising money for a synagogue under the leadership of Morris Coplan.

These early fundraising efforts were initially unsuccessful as the fledgling congregation met in the Florence Masonic Lodge. In 1905, the rabbi from Huntsville’s congregation would come to Florence once a month to lead services. The following year, the congregation officially incorporated as “Congregation B’nai Israel of the Tri-Cities” and was served by two part-time rabbis. The congregation soon restarted their fundraising effort, soliciting contributions from Jewish communities and congregations across the region. B’nai Israel received money from congregations in Cincinnati, Nashville, St. Louis, and Birmingham. They bought property in Sheffield and held a cornerstone laying ceremony with a roster of speakers that included a local Christian minister, Sheffield’s mayor, and Rabbi Isadore Lewinthal of Nashville. Completed in 1908, the building was rather modest, with an outhouse instead of indoor plumbing. At the time, the congregation had twenty-five members and $350 in annual income. An estimated 110 Jews lived in the Tri-Cities in 1907.

In the late-nineteenth century, the Jewish population of the Shoals grew as the area attracted new industry and Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. Most owned stores in one of the Tri-Cities. In 1900, there were seven Jewish-owned stores in Florence, five in Sheffield, and two in Tuscumbia. One of these stores was owned by Morris Coplan, who left Russia in 1881, arriving in New York. After spending several years in Nashville, Coplan moved to Florence in 1887. He and his wife Lena had nine children. He opened a short-lived dry goods store before finding success with a grocery business. According to the local newspaper, Coplan did not limit himself to selling food but also dealt in furs, hides, beeswax, tallow, and “all kinds of junk.” Coplan became a respected local businessman, winning election to the Florence City Council in 1901. While his political opponent attempted to make an issue out of Coplan's Jewishness, Coplan defeated him and served several terms on the council. When he died suddenly in 1910, Rabbi Max Samfield of Memphis conducted the funeral.

Organized Jewish Life

Coplan’s Jewish funeral reflected Tri-City Jews' desire to maintain their religious traditions. As early as 1884, Florence Jews began to pray together, holding lay-led Rosh Hashanah services in the local Masonic Temple. Five years later, the Sheffield Land, Iron, and Coal Company—owned by the Moses brothers—deeded land to the town for a cemetery, including three acres that were specifically set aside for use as a Jewish burial ground. By the end of the 1890s, there was a growing number of Jewish children in the area, and parents organized a religious school with the assistance of Huntsville’s Rabbi Nathan Mitchnic. In 1900, Jews in the Tri-Cities began to discuss forming a congregation and building a synagogue. Calling themselves B’nai Israel (Children of Israel), the group began raising money for a synagogue under the leadership of Morris Coplan.

These early fundraising efforts were initially unsuccessful as the fledgling congregation met in the Florence Masonic Lodge. In 1905, the rabbi from Huntsville’s congregation would come to Florence once a month to lead services. The following year, the congregation officially incorporated as “Congregation B’nai Israel of the Tri-Cities” and was served by two part-time rabbis. The congregation soon restarted their fundraising effort, soliciting contributions from Jewish communities and congregations across the region. B’nai Israel received money from congregations in Cincinnati, Nashville, St. Louis, and Birmingham. They bought property in Sheffield and held a cornerstone laying ceremony with a roster of speakers that included a local Christian minister, Sheffield’s mayor, and Rabbi Isadore Lewinthal of Nashville. Completed in 1908, the building was rather modest, with an outhouse instead of indoor plumbing. At the time, the congregation had twenty-five members and $350 in annual income. An estimated 110 Jews lived in the Tri-Cities in 1907.

Although the members of B’nai Israel had worked together to raise money to build a synagogue, there was tremendous disagreement over the style of worship. In 1918, the board debated whether to hire a Reform rabbi to lead High Holiday services. One faction, led by Lithuanian-born Philip Olim, objected, desiring to worship in the Orthodox manner. This dispute went on for a while. In 1919 the board polled the membership and found that a majority preferred Reform. They then decided to raise money to hire a rabbi and contacted the Reform seminary, Hebrew Union College, to find a candidate for the position. The congregation’s Orthodox members opposed this plan, and B’nai Israel was unable to raise enough money to hire a Reform rabbi. In 1922, the congregation voted to hold two different High Holiday services, one Orthodox and one Reform, and asked for a student rabbi from HUC who could lead both. A few years later, the congregation hired a rabbi trained at the more traditional Jewish Theological Seminary to lead High Holiday services. In 1926, the congregation voted to become an Orthodox congregation.

This Orthodoxy was short-lived as B’nai Israel’s members became more assimilated and sought a style of Judaism that better fit their circumstances living in a small Jewish community in the northwest corner of Alabama. By the late 1930s, B’nai Israel had instituted the Reform confirmation ceremony with Rabbi Morris Newfield of Birmingham leading it. By the early 1940s, B’nai Israel had joined the Reform Union of American Hebrew Congregations and had hired Luitpold Wallach as their first full-time rabbi. Wallach, a refugee from Nazi Germany, served the congregation until 1943. Four years later, the congregation hired their next full-time rabbi, Charles Mantinband, who led B’nai Israel until 1952. Under Mantinband’s leadership, the congregation reached its peak of fifty-seven members.

In addition to B’nai Israel, Tri-City Jews formed other Jewish organizations, which often focused on charitable projects. In 1904, they founded a Tri-Cities lodge of B’nai B’rith, which raised money for the Levi Hospital in Hot Springs, Arkansas, the New Orleans Jewish Children’s Home, and the B’nai B’rith Home for the Elderly in Memphis. In 1920, local women founded a chapter of the National Council of Jewish Women. Although the group raised money for both Jewish and non-Jewish causes, they focused much of their attention on supporting the synagogue, helping to pay for needed repairs to the building and buying a new fence for the cemetery. They also ran the congregation’s Sunday school. Later, the group officially became the temple Sisterhood.

B’nai Israel was not a typical Southern Reform congregation. While Zionism was unpopular among most Southern Reform Jews, Tri-City Jews embraced the cause. The local chapter of the National Council of Jewish Women donated money to Hadassah, the largest women’s Zionist organization. After Israel was established in 1948, the members of B’nai Israel were strong supporters of the Jewish state, with many buying Israel bonds and sending over packages of food and clothing. When Israel’s first Prime Minister David Ben Gurion came to the area to visit the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), he was met by a delegation from B’nai Israel.

This Orthodoxy was short-lived as B’nai Israel’s members became more assimilated and sought a style of Judaism that better fit their circumstances living in a small Jewish community in the northwest corner of Alabama. By the late 1930s, B’nai Israel had instituted the Reform confirmation ceremony with Rabbi Morris Newfield of Birmingham leading it. By the early 1940s, B’nai Israel had joined the Reform Union of American Hebrew Congregations and had hired Luitpold Wallach as their first full-time rabbi. Wallach, a refugee from Nazi Germany, served the congregation until 1943. Four years later, the congregation hired their next full-time rabbi, Charles Mantinband, who led B’nai Israel until 1952. Under Mantinband’s leadership, the congregation reached its peak of fifty-seven members.

In addition to B’nai Israel, Tri-City Jews formed other Jewish organizations, which often focused on charitable projects. In 1904, they founded a Tri-Cities lodge of B’nai B’rith, which raised money for the Levi Hospital in Hot Springs, Arkansas, the New Orleans Jewish Children’s Home, and the B’nai B’rith Home for the Elderly in Memphis. In 1920, local women founded a chapter of the National Council of Jewish Women. Although the group raised money for both Jewish and non-Jewish causes, they focused much of their attention on supporting the synagogue, helping to pay for needed repairs to the building and buying a new fence for the cemetery. They also ran the congregation’s Sunday school. Later, the group officially became the temple Sisterhood.

B’nai Israel was not a typical Southern Reform congregation. While Zionism was unpopular among most Southern Reform Jews, Tri-City Jews embraced the cause. The local chapter of the National Council of Jewish Women donated money to Hadassah, the largest women’s Zionist organization. After Israel was established in 1948, the members of B’nai Israel were strong supporters of the Jewish state, with many buying Israel bonds and sending over packages of food and clothing. When Israel’s first Prime Minister David Ben Gurion came to the area to visit the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), he was met by a delegation from B’nai Israel.

The twentieth Century

The first half of the twentieth century was a time of significant change in the Tri-Cities. During World War I, the federal government built a large hydroelectric dam and two nitrate plants to make war material. During the New Deal, the TVA brought increased industry and population. Florence’s population grew from 6,700 in 1910 to over 15,000 on the eve of World War II. Some of these new residents were Jews who were drawn the region’s growing economic opportunity.

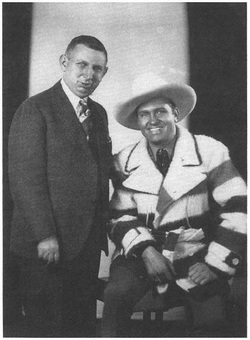

Samuel Israel left Lithuania in 1909 when he was 18 years old, settling in Sheffield. He initially worked as a clerk in a grocery store and lived as a boarder in the home of Phillip Olim, another Lithuanian Jew who owned a dry goods store. In 1912, he married Bessie Kreisman, the daughter of another Jewish dry goods store owner in Sheffield. Israel later opened a wholesale grocery business. After World War II, Israel founded the Paper and Chemical Supply Company, which grew into a very successful business. Israel was community-minded, helping to get the Muscle Shoals Airport built and supporting various charitable causes, including the Northwest Alabama Rehabilitation Center. He served on many local non-profit boards and worked to improve adult literacy across the state. The area chamber of commerce named Israel its citizen of the year. When he died in 1991, he was eulogized in the Congressional Record by Alabama Senator Howell Heflin.

The first half of the twentieth century was a time of significant change in the Tri-Cities. During World War I, the federal government built a large hydroelectric dam and two nitrate plants to make war material. During the New Deal, the TVA brought increased industry and population. Florence’s population grew from 6,700 in 1910 to over 15,000 on the eve of World War II. Some of these new residents were Jews who were drawn the region’s growing economic opportunity.

Samuel Israel left Lithuania in 1909 when he was 18 years old, settling in Sheffield. He initially worked as a clerk in a grocery store and lived as a boarder in the home of Phillip Olim, another Lithuanian Jew who owned a dry goods store. In 1912, he married Bessie Kreisman, the daughter of another Jewish dry goods store owner in Sheffield. Israel later opened a wholesale grocery business. After World War II, Israel founded the Paper and Chemical Supply Company, which grew into a very successful business. Israel was community-minded, helping to get the Muscle Shoals Airport built and supporting various charitable causes, including the Northwest Alabama Rehabilitation Center. He served on many local non-profit boards and worked to improve adult literacy across the state. The area chamber of commerce named Israel its citizen of the year. When he died in 1991, he was eulogized in the Congressional Record by Alabama Senator Howell Heflin.

Louis Rosenbaum was civic-minded. In 1937, he saved the Florence First United Methodist Church from losing its building through foreclosure, lending the church the money to pay off its mortgage. Louis and Stanley donated $40,000 to help fund the city’s first public library. Louis was also committed to the Jewish community, serving as president of B’nai Israel seven different times between 1924 and 1953.

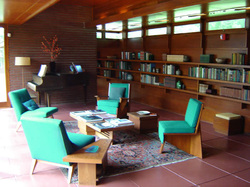

Perhaps the Rosenbaum family’s most lasting legacy in Florence is the house that Louis had built for Stanley and his new wife Mildred in 1938. Stanley Rosenbaum had met Mildred Bookholtz, a former model, in New York, and she brought her sophisticated, big-city tastes with her when she moved to Florence. To design their first home, they hired the famous architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Based on Wright’s new Usonian design, which was intended to be more affordable, the 1,500-square-foot, three-bedroom home was completed in 1939 at a cost of $14,000. Later, Wright designed an addition to the home, which remains the only Frank Lloyd Wright building in Alabama. While Stanley died in 1983, Mildred continued to live in the house until 1999, when she sold it to the city of Florence for $75,000. The city then spent over $600,000 fully restoring the house before opening it as a museum.

The cosmopolitanism reflected in the Rosenbaum house also informed the family’s racial views. Both Louis and Stanley Rosenbaum were racial progressives in the era of de jure segregation; they helped to found a local chapter of the Alabama Council on Human Relations, which advocated for racial equality. When the Ford Motor Company opened a factory in Sheffield, black workers were not allowed to eat in the cafeteria. Stanley called Ford’s corporate headquarters in Detroit and convinced the company to integrate the cafeteria. When the city’s black library needed significant repairs, Stanley used his position on the library board to tear it down and integrate the city’s white library. He worked closely with the Anti-Defamation League to keep tabs on the local Ku Klux Klan, who later burned a cross in his yard. After selling the theater business, Rosenbaum taught English at a local state college, and his activism prompted Governor George Wallace to try to get him fired. Despite these pressures, Rosenbaum was not afraid of speaking out on racial issues.

Perhaps the Rosenbaum family’s most lasting legacy in Florence is the house that Louis had built for Stanley and his new wife Mildred in 1938. Stanley Rosenbaum had met Mildred Bookholtz, a former model, in New York, and she brought her sophisticated, big-city tastes with her when she moved to Florence. To design their first home, they hired the famous architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Based on Wright’s new Usonian design, which was intended to be more affordable, the 1,500-square-foot, three-bedroom home was completed in 1939 at a cost of $14,000. Later, Wright designed an addition to the home, which remains the only Frank Lloyd Wright building in Alabama. While Stanley died in 1983, Mildred continued to live in the house until 1999, when she sold it to the city of Florence for $75,000. The city then spent over $600,000 fully restoring the house before opening it as a museum.

The cosmopolitanism reflected in the Rosenbaum house also informed the family’s racial views. Both Louis and Stanley Rosenbaum were racial progressives in the era of de jure segregation; they helped to found a local chapter of the Alabama Council on Human Relations, which advocated for racial equality. When the Ford Motor Company opened a factory in Sheffield, black workers were not allowed to eat in the cafeteria. Stanley called Ford’s corporate headquarters in Detroit and convinced the company to integrate the cafeteria. When the city’s black library needed significant repairs, Stanley used his position on the library board to tear it down and integrate the city’s white library. He worked closely with the Anti-Defamation League to keep tabs on the local Ku Klux Klan, who later burned a cross in his yard. After selling the theater business, Rosenbaum taught English at a local state college, and his activism prompted Governor George Wallace to try to get him fired. Despite these pressures, Rosenbaum was not afraid of speaking out on racial issues.

The local population continued to grow during and after World War II, with Florence doubling its population between 1940 and 1960. B’nai Israel grew as well, increasing from seventeen members in 1945 to fifty-eight in 1962. When faced with the need for significant repairs on their synagogue, the members of B’nai Israel voted to build a new temple. This new temple, now located across the river in Florence, was completed in 1954 and included an auditorium as well as classrooms. When the number of students in the religious school spiked in 1958, with 46 children, they added three additional classrooms to the building.

Rabbi Harry Merfeld led the congregation in its new building from 1954 to 1956. He was replaced by Rabbi Joseph Gallinger, who served as the congregation’s spiritual leader for the next nineteen years—the longest tenure of any rabbi at B’nai Israel. In 1982, the congregation hired Rabbi Peter Haas, who was a professor of religion at Vanderbilt University. Haas drove down from Nashville each week to lead services at B’nai Israel. As of 2017, the congregation is served by Nancy Tunick, a cantorial soloist who comes to Florence every other week from Nashville to lead services.

Rabbi Harry Merfeld led the congregation in its new building from 1954 to 1956. He was replaced by Rabbi Joseph Gallinger, who served as the congregation’s spiritual leader for the next nineteen years—the longest tenure of any rabbi at B’nai Israel. In 1982, the congregation hired Rabbi Peter Haas, who was a professor of religion at Vanderbilt University. Haas drove down from Nashville each week to lead services at B’nai Israel. As of 2017, the congregation is served by Nancy Tunick, a cantorial soloist who comes to Florence every other week from Nashville to lead services.

The Jewish Community in Florence/Sheffield Today

As late as the 1960s, Jews still owned several businesses in downtown Florence and Sheffield, but over the next two decades, most of these went out of business. The rise of chain stores, the construction of the Regency Square Mall, and the retirement of store owners with no children interested in taking over the family business all contributed to the decline of the Jewish family business.

Today, most Tri-City Jews are professionals; none are involved in retail trade. Despite these changes, the Jewish community remains strong, if small. B’nai Israel left the UAHC in the late 1980s because they felt the Reform union was not doing enough to help small congregations like them. They still have been able to thrive as an independent congregation and have been very active in local interfaith activities. Two members, Stanley Goldstein and Richard Peshkin, helped to found the Shoals Interfaith Council in 1999, which includes several local churches in addition to B’nai Israel. The Interfaith Council, under the leadership of Stanley Goldstein, held a large Holocaust commemoration symposium in 2004 that featured six days of guest speakers and programs.

In 2001, B’nai Israel had thirty-five members and an active religious school. The ongoing activity of Jewish life in the area is a testament to the tenactiy of the Tri-City Jewish community, and bodes well for the future of Jewish life along the shoals of northwest Alabama.

Today, most Tri-City Jews are professionals; none are involved in retail trade. Despite these changes, the Jewish community remains strong, if small. B’nai Israel left the UAHC in the late 1980s because they felt the Reform union was not doing enough to help small congregations like them. They still have been able to thrive as an independent congregation and have been very active in local interfaith activities. Two members, Stanley Goldstein and Richard Peshkin, helped to found the Shoals Interfaith Council in 1999, which includes several local churches in addition to B’nai Israel. The Interfaith Council, under the leadership of Stanley Goldstein, held a large Holocaust commemoration symposium in 2004 that featured six days of guest speakers and programs.

In 2001, B’nai Israel had thirty-five members and an active religious school. The ongoing activity of Jewish life in the area is a testament to the tenactiy of the Tri-City Jewish community, and bodes well for the future of Jewish life along the shoals of northwest Alabama.

Sources

Coleman, Erwin M. “A History of Temple B’nai Israel, Florence, Alabama.”