Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Little Rock, Arkansas

Historical Overview

|

Little Rock, Arkansas’s capital city, sits on the Arkansas River in Pulaski County. Not only is the site geographically central within Arkansas, it also marks the meeting point of three of the state’s defining geographic features: the foothills of the Ozark Plateau, the Mississippi River Alluvial Plain and the West Gulf Coastal Plain. The Quapaw Nation occupied the eventual site of Little Rock before 1700 and remained there until being displaced in 1824.

Little Rock gets its name from a rocky outcrop along the Arkansas River that European travelers had noted by 1722. By the end of the 18th century it became known as “le Petit Rocher” (the little rock). A permanent Euro-American settlement developed there in 1820 and soon emerged as the capital of the recently formed Arkansas Territory. |

Jewish settlers first arrived in the nascent capital in the 1830s, and their numbers grew modestly through 1860. The Jewish community grew more quickly in the late 19th century, and approximately 1,000 Jews called Little Rock home in 1905. Little Rock Jews established and participated in a number of Jewish institutions over more than 150 years, and while the Jewish population has declined somewhat since its 20th-century peak, Little Rock still boasts two active synagogues and other Jewish organizations as of 2024.

Early Jewish Settlers

The earliest recorded Jewish settlers in Little Rock were Jacob, Hyman, and Levi Mitchell, immigrants from Galicia (Poland) who arrived in the 1830s. In the 1840s Jacob Mitchell ran an auction house in Little Rock, owned a hotel in Hot Springs, and operated a stagecoach route between the two towns. Newspaper records show that Hyman Mitchell was in business for himself in 1845, and Levi Mitchell appears as a partner in advertisements two years later. Evidence suggests that all three Mitchell brothers left Little Rock by 1850, but a few other Jewish newcomers had arrived in the meantime and more would arrive soon.

Among the other early Jews were Jonas Levy, who began selling fire and marine insurance in Little Rock by 1841. Levy served as mayor in 1844, but he relocated his family to Memphis in the early 1850s. (Some sources mistakenly indicate that Levy was the mayor of Little Rock during the Civil War.) Morris and Margaret Navra moved to Little Rock in the 1850s and opened a small grocery that specialized in tea and fruit. While the 1860 census lists his birthplace as Poland, she came from Frankfurt am Main. Both Jonas Levy and the Navra family had additional family members in town, some of whom stayed for short periods and some of whom put down deeper roots.

Although Little Rock had served as the territorial capital since 1821 and the state capital since 1836, it remained a small town in a sparsely populated state until after the Civil War. As of the 1860 census, the town’s population stood at 3,727 people, and Pulaski County was home to 11,699 people, nearly 30 percent of whom were enslaved. The small number of Jewish residents, primarily European-born immigrants, generally lacked the means to purchase enslaved Black workers. Like other small-time business people and urban dwellers, those who did enslave Black workers did so on a small scale. Jonas Levy, for instance, appears in the 1850 U.S. Census Slave Schedules as the owner of a ten-year-old girl. Isaac Levy of nearby Big Rock—presumably Jonas’s brother—enslaved a 26-year-old woman at the time. The 1860 census does not list any known Jewish settlers as enslavers.

Among the other early Jews were Jonas Levy, who began selling fire and marine insurance in Little Rock by 1841. Levy served as mayor in 1844, but he relocated his family to Memphis in the early 1850s. (Some sources mistakenly indicate that Levy was the mayor of Little Rock during the Civil War.) Morris and Margaret Navra moved to Little Rock in the 1850s and opened a small grocery that specialized in tea and fruit. While the 1860 census lists his birthplace as Poland, she came from Frankfurt am Main. Both Jonas Levy and the Navra family had additional family members in town, some of whom stayed for short periods and some of whom put down deeper roots.

Although Little Rock had served as the territorial capital since 1821 and the state capital since 1836, it remained a small town in a sparsely populated state until after the Civil War. As of the 1860 census, the town’s population stood at 3,727 people, and Pulaski County was home to 11,699 people, nearly 30 percent of whom were enslaved. The small number of Jewish residents, primarily European-born immigrants, generally lacked the means to purchase enslaved Black workers. Like other small-time business people and urban dwellers, those who did enslave Black workers did so on a small scale. Jonas Levy, for instance, appears in the 1850 U.S. Census Slave Schedules as the owner of a ten-year-old girl. Isaac Levy of nearby Big Rock—presumably Jonas’s brother—enslaved a 26-year-old woman at the time. The 1860 census does not list any known Jewish settlers as enslavers.

Whether or not local Jews owned enslaved people, they participated in a slave-based economy. Arkansas’s enslaved population accounted for a quarter of all residents in 1860, but that number was significantly higher in eastern Arkansas, where cotton production generated much of the state’s wealth. Jews in Little Rock and nearby towns could also uphold slavery without owning slaves themselves. In 1847 Levi Mitchell, then of Hot Springs, offered a reward for an escaped enslaved person who was the legal property of “Mrs. Bush of Conway County.” According to an ad that Mitchell placed in the Weekly Arkansas Gazette, an enslaved man named Ned ran away from the hot springs after taking a $100 bill from a white visitor. Levi Mitchell offered a cash reward for his return either to the Mitchell business in Hot Springs or to Hyman Mitchell in Little Rock.

Before the Civil War, local Jews followed news of the rising hostilities. In 1860 Morris Navra co-signed a letter in support of a candidate for colonel of the local Arkansas Militia regiment that recognized the “necessity to organize our military forces” in case of civil war and praised the candidate’s “chivalry and devotion to the South.” After the war began, local Jews contributed to the Confederate war effort. German speaking immigrant Albert Cohen, for example, reached the rank of captain in the Confederate Army Corps of Engineers and used his expertise in minerals to help produce sulfur for use in gunpowder.

Before the Civil War, local Jews followed news of the rising hostilities. In 1860 Morris Navra co-signed a letter in support of a candidate for colonel of the local Arkansas Militia regiment that recognized the “necessity to organize our military forces” in case of civil war and praised the candidate’s “chivalry and devotion to the South.” After the war began, local Jews contributed to the Confederate war effort. German speaking immigrant Albert Cohen, for example, reached the rank of captain in the Confederate Army Corps of Engineers and used his expertise in minerals to help produce sulfur for use in gunpowder.

Reconstruction and the Late 19th Century

Little Rock grew considerably in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, and, although the town faced a period of relative stagnation during the 1870s, the population boomed again in the last two decades of the 19th century. The Jewish population followed suit, and Jewish-owned businesses played a significant role in the local economy. A few Jewish families experienced extraordinary financial success, while others operated more modest businesses. Jews also continued to move in and out of the area, depending in large part on their economic fortunes.

The post-Civil War years proved turbulent. Along with the national economic depression brought about by the Panic of 1873, a contested gubernatorial election in 1872 led to the outbreak of political violence in 1874. The conflict, known as the Brooks-Baxter War, took place between two factions of the Republican Party and resulted in a series of small battles that claimed an estimated 200 lives before federal intervention resolved the dispute. Three Jews reportedly received injuries at a battle in New Gascony, just south of Little Rock, and the Little Rock Concordia Association (a Jewish social organization) briefly converted its meeting rooms to a makeshift hospital. For the state as a whole, the aftermath of the Brooks-Baxter War led to the end of Reconstruction in Arkansas following the adoption of the state’s 1874 constitution.

Despite economic and political upheaval, Jewish families had begun to set down deep roots in Arkansas by 1870. Nineteen-year-old immigrant Gus Blass, for instance, appears in the 1870 census living with his brother Louis. Gus Blass reported a $900 estate and made his living as a merchant. A decade later he had married Bertha Katzenstein (an Ohio native), and the couple lived with their two children, Gus’s brother Jacob, several of Bertha’s family members, and three Black domestic workers. The family business, Gus Blass & Co., remained a major retailer in Little Rock and Arkansas for generations. Sophia Blass—a sister of Louis, Gus, and Jacob—married into the Kempner family, which had been in Hot Springs since the 1850s and moved to Little Rock by 1870. Mark M. Cohn, whose wife Rachael was also a Kempner, moved from Arkadelphia to Little Rock around 1880. His business, the M. M. Cohn Company, operated well into the 20th century and became known as the most high end of the local department stores.

The post-Civil War years proved turbulent. Along with the national economic depression brought about by the Panic of 1873, a contested gubernatorial election in 1872 led to the outbreak of political violence in 1874. The conflict, known as the Brooks-Baxter War, took place between two factions of the Republican Party and resulted in a series of small battles that claimed an estimated 200 lives before federal intervention resolved the dispute. Three Jews reportedly received injuries at a battle in New Gascony, just south of Little Rock, and the Little Rock Concordia Association (a Jewish social organization) briefly converted its meeting rooms to a makeshift hospital. For the state as a whole, the aftermath of the Brooks-Baxter War led to the end of Reconstruction in Arkansas following the adoption of the state’s 1874 constitution.

Despite economic and political upheaval, Jewish families had begun to set down deep roots in Arkansas by 1870. Nineteen-year-old immigrant Gus Blass, for instance, appears in the 1870 census living with his brother Louis. Gus Blass reported a $900 estate and made his living as a merchant. A decade later he had married Bertha Katzenstein (an Ohio native), and the couple lived with their two children, Gus’s brother Jacob, several of Bertha’s family members, and three Black domestic workers. The family business, Gus Blass & Co., remained a major retailer in Little Rock and Arkansas for generations. Sophia Blass—a sister of Louis, Gus, and Jacob—married into the Kempner family, which had been in Hot Springs since the 1850s and moved to Little Rock by 1870. Mark M. Cohn, whose wife Rachael was also a Kempner, moved from Arkadelphia to Little Rock around 1880. His business, the M. M. Cohn Company, operated well into the 20th century and became known as the most high end of the local department stores.

Although Arkansas had long held a reputation for its frontier conditions and a lack of sophistication, Little Rock had developed considerably by the time the Mark and Rachael Cohn arrived. The B’nai B’rith representative and journalist Charles Wessolowsky visited in 1878 and reported favorably on the town in the American Jewish Israelite. He wrote that “intelligence and respectability will compare here favorably with that of almost any city… We were deceived in our ideas that the people of Arkansas are ruffianly and uncivilized.”

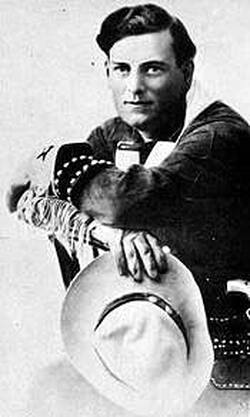

Max Aaronson, better known as Broncho Billy, early 20th century.

Max Aaronson, better known as Broncho Billy, early 20th century.

As the late 19th century progressed, Jewish newcomers to Little Rock operated a variety of businesses. Retail predominated, as it did in other locations, but Jewish residents also worked in entertainment, banking, and real estate, as well as service industries such as laundry, insurance, and lodging. Some Little Rock Jews became involved in lumber and agriculture, industries that dominated the rural parts of the state. Austrian native Charles Abeles arrived in 1880 and established a lumber company that prospered quickly. Within seven years, the C.T. Abeles Company offered a full range of lumber products and competed with large St. Louis manufacturers. A number of Jewish merchants entered the cotton trade, including Adolph Hamburg, a native of the Netherlands. The Ad Hamberg and Company Cotton Buyers served as a state manager for the St. Louis-based Lesser-Goldman Company, at one point the United States’ largest domestic shipper of cotton.

For each prominent Jewish family in Little Rock, several others lived more modest lives. Many such families also proved highly mobile. Henry and Esther Aronson, for example, came to Little Rock with their five children in the late 1870s. A sixth child, Max, was born in 1880. Henry worked as a traveling salesman, and the family was able to hire a ten-year-old Black girl to live with them and perform domestic work. Within a few years the family had relocated to Pine Bluff, and they moved again to St. Louis by 1890. Their son Max became a vaudeville performer and then gained recognition (under the name Gilbert M. Anderson) as an actor, writer, and director in silent films—especially for his character Broncho Billy. A daughter, St. Louis-born Leona Anderson, also worked as a performer.

For each prominent Jewish family in Little Rock, several others lived more modest lives. Many such families also proved highly mobile. Henry and Esther Aronson, for example, came to Little Rock with their five children in the late 1870s. A sixth child, Max, was born in 1880. Henry worked as a traveling salesman, and the family was able to hire a ten-year-old Black girl to live with them and perform domestic work. Within a few years the family had relocated to Pine Bluff, and they moved again to St. Louis by 1890. Their son Max became a vaudeville performer and then gained recognition (under the name Gilbert M. Anderson) as an actor, writer, and director in silent films—especially for his character Broncho Billy. A daughter, St. Louis-born Leona Anderson, also worked as a performer.

An Organized Jewish Community

At the beginning of the Civil War, Little Rock Jews had just begun to organize communal institutions. A letter published in the American Israelite on October 5th, 1860, reported that Isaac Levy (mentioned above) had died on Yom Kippur, which had “occasioned the Israelites of this city to buy a piece of land for a burial ground.” The author speculates that a congregation might follow the establishment of a cemetery, but adds that “beside Morris Navara [sic], there is no place in the South where the Israelites do less and want to know less of their religion than in Little Rock.”

Local Jews did, in fact, found additional institutions in the following years. Some accounts give 1864 as the founding date of the Concordia Association (also referred to as the Concordia Club), a social organization for Jewish men, but the year may have been somewhat later. Either way, the club occupied a second-story hall on West Markham Street between Louisiana and Capitol Streets by the early 1870s, and they dedicated a more stately space on East Markham Street in 1882.

Around the time that Little Rock Jews established the Concordia Association, they also came together to organize a congregation. In 1866 they purchased a Torah scroll and a shofar (ram’s horn) for High Holiday observances. The group was first known simply as the “Little Rock Congregation” but took the name Congregation B’nai Israel upon its formal incorporation in 1867. The congregation initially met in a rented room on East Markham Street, which they dedicated as a synagogue in August 1867. Samuel Peck of Memphis acted as hazan (prayer leader) for the event, and he continued to serve the congregation at least into 1868. Approximately 40 households belonged to Congregation B’nai Israel in 1867.

In 1872 the congregation built a synagogue downtown at 304 Center Street. During that decade the community supported a B’nai B’rith lodge, a Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Society, and the Hebrew Children Mite Society, which raised funds for the Association for the Relief of Jewish Widows and Orphans in New Orleans (later known as the Jewish Children’s Home). The Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Society, founded in 1867, had been particularly active in the fundraising efforts for the new building.

Congregation B’nai Israel adopted several Reform practices in the 1870s. They hired spiritual leader Jacob Bloch in 1872, and he used the title “reverend” in keeping with American Reform practice at the time. The congregation also adopted English language services in the style of Isaac Mayer Wise’s Minhag America and employed an organ player. In 1873 Congregation B’nai Israel became a charter member of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (later known as the Union for Reform Judaism), and by 1875 the congregation no longer required men to wear head coverings during prayer services. Reverend Bloch helped oversee the establishment of a religious school, which enrolled 69 students in 1872, and introduced confirmation ceremonies the following year.

A minority of local Jews objected to the reforms that Congregation B’nai Israel had adopted, and agitated for a return to traditional worship. After that effort proved unsuccessful, a splinter group formed in 1879 and began to hold Orthodox services in rented quarters at Casino Hall. The leadership of the new group included Samuel Lasker and Isaac Adelman, both immigrants from Polish territories who had formerly belonged to B’nai Israel. In time, this traditional contingent formed their own congregation, Agudath Achim. (Early-20th-century sources refer to the congregation as Agudas Achim, reflecting an Ashkenazi pronunciation.)

B’nai Israel remained the larger and more established congregation, but it struggled to retain a spiritual leader during the 1880s. Reverend Bloch departed for a pulpit in Oregon at the end of 1880, and three different rabbis served the congregation during the subsequent decade. The arrival of Rabbi Charles Rubenstein in 1891 provided some stability; he stayed for six years and played a leading role in the construction of a new synagogue.

By the time that B’nai Israel dedicated its new synagogue in 1897, the city’s population had reached nearly 38,000—tripling the number of residents reported in 1870. The Jewish community had grown as well. B’nai Israel claimed nearly 200 members and had outgrown the 1872 synagogue. The congregation’s new temple, completed in 1897 at Broadway and Capitol Streets, was both larger and more ornate than the original building; the yellow-brick edifice included numerous stained glass windows, a dramatic, a 70-foot tower rose from the southwest corner of the building, and a large, central dome capped the sanctuary. In addition to local officials and dignitaries, the dedication ceremony featured rabbis from cities in and near Arkansas, and Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, founder of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations.

Local Jews did, in fact, found additional institutions in the following years. Some accounts give 1864 as the founding date of the Concordia Association (also referred to as the Concordia Club), a social organization for Jewish men, but the year may have been somewhat later. Either way, the club occupied a second-story hall on West Markham Street between Louisiana and Capitol Streets by the early 1870s, and they dedicated a more stately space on East Markham Street in 1882.

Around the time that Little Rock Jews established the Concordia Association, they also came together to organize a congregation. In 1866 they purchased a Torah scroll and a shofar (ram’s horn) for High Holiday observances. The group was first known simply as the “Little Rock Congregation” but took the name Congregation B’nai Israel upon its formal incorporation in 1867. The congregation initially met in a rented room on East Markham Street, which they dedicated as a synagogue in August 1867. Samuel Peck of Memphis acted as hazan (prayer leader) for the event, and he continued to serve the congregation at least into 1868. Approximately 40 households belonged to Congregation B’nai Israel in 1867.

In 1872 the congregation built a synagogue downtown at 304 Center Street. During that decade the community supported a B’nai B’rith lodge, a Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Society, and the Hebrew Children Mite Society, which raised funds for the Association for the Relief of Jewish Widows and Orphans in New Orleans (later known as the Jewish Children’s Home). The Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Society, founded in 1867, had been particularly active in the fundraising efforts for the new building.

Congregation B’nai Israel adopted several Reform practices in the 1870s. They hired spiritual leader Jacob Bloch in 1872, and he used the title “reverend” in keeping with American Reform practice at the time. The congregation also adopted English language services in the style of Isaac Mayer Wise’s Minhag America and employed an organ player. In 1873 Congregation B’nai Israel became a charter member of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (later known as the Union for Reform Judaism), and by 1875 the congregation no longer required men to wear head coverings during prayer services. Reverend Bloch helped oversee the establishment of a religious school, which enrolled 69 students in 1872, and introduced confirmation ceremonies the following year.

A minority of local Jews objected to the reforms that Congregation B’nai Israel had adopted, and agitated for a return to traditional worship. After that effort proved unsuccessful, a splinter group formed in 1879 and began to hold Orthodox services in rented quarters at Casino Hall. The leadership of the new group included Samuel Lasker and Isaac Adelman, both immigrants from Polish territories who had formerly belonged to B’nai Israel. In time, this traditional contingent formed their own congregation, Agudath Achim. (Early-20th-century sources refer to the congregation as Agudas Achim, reflecting an Ashkenazi pronunciation.)

B’nai Israel remained the larger and more established congregation, but it struggled to retain a spiritual leader during the 1880s. Reverend Bloch departed for a pulpit in Oregon at the end of 1880, and three different rabbis served the congregation during the subsequent decade. The arrival of Rabbi Charles Rubenstein in 1891 provided some stability; he stayed for six years and played a leading role in the construction of a new synagogue.

By the time that B’nai Israel dedicated its new synagogue in 1897, the city’s population had reached nearly 38,000—tripling the number of residents reported in 1870. The Jewish community had grown as well. B’nai Israel claimed nearly 200 members and had outgrown the 1872 synagogue. The congregation’s new temple, completed in 1897 at Broadway and Capitol Streets, was both larger and more ornate than the original building; the yellow-brick edifice included numerous stained glass windows, a dramatic, a 70-foot tower rose from the southwest corner of the building, and a large, central dome capped the sanctuary. In addition to local officials and dignitaries, the dedication ceremony featured rabbis from cities in and near Arkansas, and Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, founder of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations.

The Early 20th Century

Little Rock continued to grow rapidly after the turn of the century as a commercial hub, a seat of government, and (to a smaller extent) an industrial center. Infrastructure improvements and economic growth gave the city a more cosmopolitan feel, even as racial segregation became more rigid. Meanwhile, Jewish Little Rock experienced its own changes. The arrival of larger numbers of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe had already begun to reshape Jewish life in the United States by 1900. Although Little Rock received only a tiny fraction of these newcomers, they played significant roles in the city’s Jewish community and in its overall development. They also contributed to continued growth of the Jewish population, which rose from approximately 650 individuals in 1878 to 1,000 in 1905.

U.S. census records show a number of Jewish Little Rock residents from Poland by 1870, and a notable contingent of Russian-born Jews had settled there by the time of the 1900 census. Abe Tenenbaum (sometimes Tanenbaum), for example, was around eighteen years old when he emigrated from Russia in 1889. Four years later he ran a junk business with Samuel Barack on Scott Street—a common occupation for Jewish immigrants—and lived in a nearby boarding house. In 1900 he lived on a predominantly Black section of Sherman Street with his wife Esther (sometimes Annie); son Martin; mother, Marie Tenenbaum; and brother-in-law Ike Baron. Within seven years the family moved to a larger home, evidence of Tenenbaum’s increasing business success. While some records refer to Tenenbaum as a hide and fur dealer, a 1918 ad details the wide variety of items that he bought and sold: “rags, bones, scrap iron, sacks, copper, brass, lead, zinc, auto tires, tubes, rubber, hides, wool, beeswax, etc.” Over time, the A. Tenenbaum Company rose to become the largest scrap and recycling operation in Arkansas.

U.S. census records show a number of Jewish Little Rock residents from Poland by 1870, and a notable contingent of Russian-born Jews had settled there by the time of the 1900 census. Abe Tenenbaum (sometimes Tanenbaum), for example, was around eighteen years old when he emigrated from Russia in 1889. Four years later he ran a junk business with Samuel Barack on Scott Street—a common occupation for Jewish immigrants—and lived in a nearby boarding house. In 1900 he lived on a predominantly Black section of Sherman Street with his wife Esther (sometimes Annie); son Martin; mother, Marie Tenenbaum; and brother-in-law Ike Baron. Within seven years the family moved to a larger home, evidence of Tenenbaum’s increasing business success. While some records refer to Tenenbaum as a hide and fur dealer, a 1918 ad details the wide variety of items that he bought and sold: “rags, bones, scrap iron, sacks, copper, brass, lead, zinc, auto tires, tubes, rubber, hides, wool, beeswax, etc.” Over time, the A. Tenenbaum Company rose to become the largest scrap and recycling operation in Arkansas.

Jewish newcomers also came from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Samuel Brier arrived in Little Rock in 1895 and initially sold drygoods. He married Bertha Trubowitz of Galveston, Texas, in 1900. According to family stories, the couple ran a fruit business from an East Markham Street storefront. When passersby mistook the shop for a restaurant and requested meals there, the couple recognized the demand for a restaurant. By 1903 they operated the Model Restaurant, which offered 25-cent meals. In 1916 they moved into a larger space on West Markham, down the street from Herman Kahn’s newly built Marion Hotel. The new venture started out as Hungarian Cafe but eventually took the name “Breier’s Fine Old Restaurant,” and it became one of the most luxurious dining environments in the city. The Breier family were mainstays of Little Rock’s Orthodox community, and they dutifully closed their business every year in observance of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur.

The traditionally observant group that split from B’nai Israel in 1879 had continued to meet in rented spaces and store fronts, and their numbers increased with the arrival of recent immigrants and their children, including the Tenenbaum and Breier families. In 1904 they organized a formal congregation and took the name Agudath Achim (Association of Brothers). The fledgling congregation quickly began raising funds for a building, and in 1907 they purchased the Second Baptist Church, which they converted into a synagogue. Russian immigrant Samuel Katzenellenbogen served as the first rabbi of Agudath Achim, a position that he held from approximately 1905 to 1920.

The traditionally observant group that split from B’nai Israel in 1879 had continued to meet in rented spaces and store fronts, and their numbers increased with the arrival of recent immigrants and their children, including the Tenenbaum and Breier families. In 1904 they organized a formal congregation and took the name Agudath Achim (Association of Brothers). The fledgling congregation quickly began raising funds for a building, and in 1907 they purchased the Second Baptist Church, which they converted into a synagogue. Russian immigrant Samuel Katzenellenbogen served as the first rabbi of Agudath Achim, a position that he held from approximately 1905 to 1920.

The establishment of Agudath Achim did not detract from the activities of B’nai Israel, the older, Reform congregation. Under the leadership of Rabbi Louis Wolsey, who served from 1899 to 1907, the congregation reached a membership of 220 households and took in more than $7,000 annually in dues and donations. By the end of Rabbi Wolsey’s tenure, the congregation had enlarged its building to accommodate new members, and its weekly religious school enrolled 156 students. B’nai Israel’s growth continued, and a decade later the congregation boasted 300 member families.

The Concordia Association remained an important part of Jewish life in Little Rock well into the 20th century. The club’s second story rooms hosted social events, primarily for the city’s more established, Reform families, and Jewish organizations used the space, as well. Because local country clubs did not admit Jewish members, the Concordia Association purchased land outside the city center for a golf course in 1917. By the 1920s, however, the group ran into financial difficulties with the combined expenses of maintaining their downtown meeting hall and developing a suburban country club. The Great Depression ultimately put an end to the Concordia Association, as both falling dues revenue and mounting debt forced the club to shut down. In the post-war decades, Jewish families belonged to the Westridge Country Club, and a few select Jews became members of the Little Rock Country Club in the 1970s.

Civic Engagement

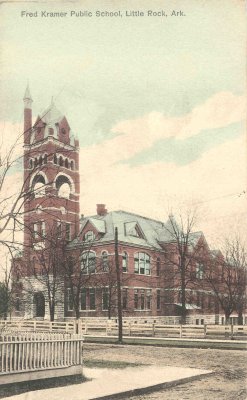

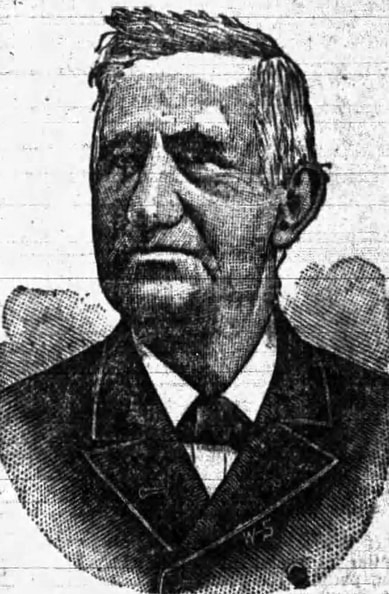

Frederick Kramer, as depicted upon the occasion of his death. Daily Arkansas Gazette, 09 September, 1896.

Frederick Kramer, as depicted upon the occasion of his death. Daily Arkansas Gazette, 09 September, 1896.

Although Little Rock Jews experienced social exclusion from country clubs and other elite, white institutions, they also played prominent roles in the civic and political life of the city beginning early in its history. Frederick Kramer, for instance, arrived in Little Rock from Prussia in the 1850s and was a founding member of B’nai Israel. In addition to becoming a successful businessman, he sat on the board of aldermen and the board of education for years, and he served as mayor from 1873 to 1875 and from 1881 to 1887. Kramer Elementary School, open until 1978, was named in his honor. Other Jewish aldermen of the late 19th century included Max Hilb and Louis Volmer.

Whereas a number of late-19th-century Jewish politicians in Little Rock were German speaking immigrants, later Eastern European Jews who involved themselves in politics were more often second-generation citizens born to immigrant parents. In part, the earlier arrivals had taken advantage of a less entrenched social hierarchy that did not distinguish as strongly between native-born and foreign-born residents (so long as they were white). By the turn of the century, when many Eastern European Jews made their way to Little Rock, local nativism had increased along with a national tide of anti-immigrant sentiments.

Among the influential children of Yiddish-speaking immigrants was Edward “Eddie” Bennett, born in 1903 to Ike and Sarah Bennett. After graduating from the Arkansas Law School he began a lifetime of involvement in the state Democratic Party. Another Jewish law school graduate and second-generation citizen was William B. Sanders, whose family moved to Little Rock from Missouri when he was young. Sanders worked for highway commissioner and real estate developer Justin Matthews and eventually took an active role in city leadership, working with the Little Rock Improvement District and the Board of Public Affairs. He also won election to the Little Rock City Council.

Even as Jewish men gained prominence in civic life and in the legal world, longtime Jewish businesses maintained their importance in the economic life of the city. Second- and third-generation members of the Blass, Cohn, Pfeifer, and Kempner families—all of whom were interrelated by marriage—continued to operate the city’s most popular retail outlets. Pfeifer Brothers and Gus Blass & Co. also opened additional locations outside of Little Rock. Jewish business owners also contributed to the city’s industrialization. In addition to the Tenebaum family’s thriving scrap and recycling business, fourth-generation Little Rock resident Gus Ottenheimer owned a large garment factory in the 1940s and 1950s, which employed as many as 650 workers.

Just as Jewish lay people occupied highly visible civic and economic positions, Jewish clergy became notable figures in the public eye. The most notable of these, Rabbi Ira Sanders, (unrelated to William B. Sanders) began a 37-year tenure at Reform congregation B’nai Israel in 1926. He had previously received his rabbinical ordination from Hebrew Union College in 1919, led a congregation in Allentown, Pennsylvania, served as an associate rabbi at a large Reform congregation in New York City, and earned a master’s degree in sociology from Columbia University. Rabbi Sanders immediately chafed at the Jim Crow practices that he encountered in the South. Shortly after his arrival he took a seat next to a Black man on a city streetcar, which led to an argument with the conductor. That experience spurred the rabbi to attack the morality of segregation in a sermon to his new congregation.

Sanders’ progressivism—a product of his rabbinical training and his time at Columbia University—led him to become involved in a number of local initiatives. In 1927 he took a leadership role in the development of the Little Rock School of Social Work, and when the new school became part of the University of Arkansas Extension Department he served as its founding dean. In 1929 he permitted three Black students to enroll in the program, but his attempt to desegregate the social work school ultimately failed due to pressure from the university. While Sanders’ liberal politics sometimes pushed against the status quo, he also became a well respected figure in and beyond Little Rock. As the sole rabbi of the state’s largest synagogue, he served at times as a spokesperson for Arkansas Jews, and his broad intellectual range and oratory skills made him a popular speaker with a variety of organizations.

Whereas a number of late-19th-century Jewish politicians in Little Rock were German speaking immigrants, later Eastern European Jews who involved themselves in politics were more often second-generation citizens born to immigrant parents. In part, the earlier arrivals had taken advantage of a less entrenched social hierarchy that did not distinguish as strongly between native-born and foreign-born residents (so long as they were white). By the turn of the century, when many Eastern European Jews made their way to Little Rock, local nativism had increased along with a national tide of anti-immigrant sentiments.

Among the influential children of Yiddish-speaking immigrants was Edward “Eddie” Bennett, born in 1903 to Ike and Sarah Bennett. After graduating from the Arkansas Law School he began a lifetime of involvement in the state Democratic Party. Another Jewish law school graduate and second-generation citizen was William B. Sanders, whose family moved to Little Rock from Missouri when he was young. Sanders worked for highway commissioner and real estate developer Justin Matthews and eventually took an active role in city leadership, working with the Little Rock Improvement District and the Board of Public Affairs. He also won election to the Little Rock City Council.

Even as Jewish men gained prominence in civic life and in the legal world, longtime Jewish businesses maintained their importance in the economic life of the city. Second- and third-generation members of the Blass, Cohn, Pfeifer, and Kempner families—all of whom were interrelated by marriage—continued to operate the city’s most popular retail outlets. Pfeifer Brothers and Gus Blass & Co. also opened additional locations outside of Little Rock. Jewish business owners also contributed to the city’s industrialization. In addition to the Tenebaum family’s thriving scrap and recycling business, fourth-generation Little Rock resident Gus Ottenheimer owned a large garment factory in the 1940s and 1950s, which employed as many as 650 workers.

Just as Jewish lay people occupied highly visible civic and economic positions, Jewish clergy became notable figures in the public eye. The most notable of these, Rabbi Ira Sanders, (unrelated to William B. Sanders) began a 37-year tenure at Reform congregation B’nai Israel in 1926. He had previously received his rabbinical ordination from Hebrew Union College in 1919, led a congregation in Allentown, Pennsylvania, served as an associate rabbi at a large Reform congregation in New York City, and earned a master’s degree in sociology from Columbia University. Rabbi Sanders immediately chafed at the Jim Crow practices that he encountered in the South. Shortly after his arrival he took a seat next to a Black man on a city streetcar, which led to an argument with the conductor. That experience spurred the rabbi to attack the morality of segregation in a sermon to his new congregation.

Sanders’ progressivism—a product of his rabbinical training and his time at Columbia University—led him to become involved in a number of local initiatives. In 1927 he took a leadership role in the development of the Little Rock School of Social Work, and when the new school became part of the University of Arkansas Extension Department he served as its founding dean. In 1929 he permitted three Black students to enroll in the program, but his attempt to desegregate the social work school ultimately failed due to pressure from the university. While Sanders’ liberal politics sometimes pushed against the status quo, he also became a well respected figure in and beyond Little Rock. As the sole rabbi of the state’s largest synagogue, he served at times as a spokesperson for Arkansas Jews, and his broad intellectual range and oratory skills made him a popular speaker with a variety of organizations.

The Mid-20th Century and Desegregation in Little Rock

Rabbi Ira Sanders

Rabbi Ira Sanders

Little Rock grew significantly over the first half of the twentieth century. Whereas the 1910 census recorded approximately 46,000 residents, that number exceeded 102,000 in 1950. The Jewish population did not grow uniformly over that period, however. Estimates of Little Rock’s Jewish population peaked at 3,000 in 1927. In 1937 the reported population dropped to 2,500, and fewer than 1,200 Jews reportedly lived in Little Rock in 1948. While these population figures may not be entirely accurate, they likely reflect some decline over the second quarter of the century.

Despite a contraction of the Jewish population, Jewish communal life continued. Congregation Agudath Achim raised money in the immediate postwar years to replace their aging stone structure. Rabbi Samuel Fox assumed the pulpit in 1949 and took the reigns of the new building project. The congregation dedicated a new synagogue on the site of their first building in 1952, and the new opening of the new facility corresponded to a revival of their religious school which offered Sunday school lessons and an afterschool cheder that met four days a week. The new building offered up-to-date facilities, but its location on a busy downtown street proved inconvenient as an increasing number of congregants relocated to newer, suburban neighborhoods. Those who arrived by car often had trouble finding parking, and Agudath Achim’s rabbis often stayed in hotels over the weekend in order to observe Shabbat in a traditional manner.

As Agudath Achim built a new structure, B’nai Israel expanded under the leadership of Rabbi Sanders. The congregation added a new education wing in 1949 and remodeled over the course of 1953 and 1954. While Jewish activity had already peaked in a number of Arkansas towns, synagogue attendance in Little Rock remained strong. Aside from some social exclusion in elite white circles, the Jewish community seemed to occupy a comfortable position in local society, but within a few years the turmoil surrounding desegregation caused increased anxiety for Little Rock Jews.

As the movement for Black civil rights gained momentum, southern Jews faced competing pressures. On one hand, national Jewish organizations such as the Anti-Defamation League and the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (later known as the Union for Reform Judaism) had publicly supported the legal battle to end segregation. On the other hand, Jewish in Little Rock and other southern cities risked segregationist backlash for even appearing to sympathize with the movement. Furthermore, the Jews of Little Rock, like co-religionists across the country, held a variety of opinions about desegregation and Black civil rights. Rabbi Ira Sanders and others supported desegregation and openly advocated for a smooth transition away from Jim Crow. A majority of local Jews—whether due to fear or indifference—took no stand on the issue. Another group sought to maintain segregation.

Following the Brown vs. Board of Education verdict in 1954, the Little Rock School Board began planning to desegregate the local education system, beginning in the 1957-1958 school year. When nine Black students registered for all-white Little Rock Central High School, Governor Orval Faubus (then running for reelection) vowed to oppose integration and deployed the Arkansas National Guard to block their entry to the school. The Federal Government intervened to enforce desegregation, but the situation provoked a local crisis.

Rabbi Ira Sanders had long supported causes related to Black civil rights, and just prior to the desegregation crisis he had spoken out in the Arkansas House of Representatives against a package of bills that aimed to circumvent the Brown vs. Board decision. In doing so, Rabbi Sanders acted in defiance of violent threats and intense pressure from segregationist groups. Following the showdown at Central High, some segregationists circulated literature that blamed the civil rights movement on a “Communist-Zionist conspiracy,” a common trope at the time. The segregationist Capital Citizens Council threatened a boycott of the large Jewish-owned department stores, demanding that they cease advertising in the pro-desegregation newspaper the Arkansas Gazette. Jewish high school students encountered pressure from white, non-Jewish peers to oppose integration. These and other incidents persuaded many Little Rock Jews to adopt a policy of self-censorship on civil rights issues.

Despite a contraction of the Jewish population, Jewish communal life continued. Congregation Agudath Achim raised money in the immediate postwar years to replace their aging stone structure. Rabbi Samuel Fox assumed the pulpit in 1949 and took the reigns of the new building project. The congregation dedicated a new synagogue on the site of their first building in 1952, and the new opening of the new facility corresponded to a revival of their religious school which offered Sunday school lessons and an afterschool cheder that met four days a week. The new building offered up-to-date facilities, but its location on a busy downtown street proved inconvenient as an increasing number of congregants relocated to newer, suburban neighborhoods. Those who arrived by car often had trouble finding parking, and Agudath Achim’s rabbis often stayed in hotels over the weekend in order to observe Shabbat in a traditional manner.

As Agudath Achim built a new structure, B’nai Israel expanded under the leadership of Rabbi Sanders. The congregation added a new education wing in 1949 and remodeled over the course of 1953 and 1954. While Jewish activity had already peaked in a number of Arkansas towns, synagogue attendance in Little Rock remained strong. Aside from some social exclusion in elite white circles, the Jewish community seemed to occupy a comfortable position in local society, but within a few years the turmoil surrounding desegregation caused increased anxiety for Little Rock Jews.

As the movement for Black civil rights gained momentum, southern Jews faced competing pressures. On one hand, national Jewish organizations such as the Anti-Defamation League and the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (later known as the Union for Reform Judaism) had publicly supported the legal battle to end segregation. On the other hand, Jewish in Little Rock and other southern cities risked segregationist backlash for even appearing to sympathize with the movement. Furthermore, the Jews of Little Rock, like co-religionists across the country, held a variety of opinions about desegregation and Black civil rights. Rabbi Ira Sanders and others supported desegregation and openly advocated for a smooth transition away from Jim Crow. A majority of local Jews—whether due to fear or indifference—took no stand on the issue. Another group sought to maintain segregation.

Following the Brown vs. Board of Education verdict in 1954, the Little Rock School Board began planning to desegregate the local education system, beginning in the 1957-1958 school year. When nine Black students registered for all-white Little Rock Central High School, Governor Orval Faubus (then running for reelection) vowed to oppose integration and deployed the Arkansas National Guard to block their entry to the school. The Federal Government intervened to enforce desegregation, but the situation provoked a local crisis.

Rabbi Ira Sanders had long supported causes related to Black civil rights, and just prior to the desegregation crisis he had spoken out in the Arkansas House of Representatives against a package of bills that aimed to circumvent the Brown vs. Board decision. In doing so, Rabbi Sanders acted in defiance of violent threats and intense pressure from segregationist groups. Following the showdown at Central High, some segregationists circulated literature that blamed the civil rights movement on a “Communist-Zionist conspiracy,” a common trope at the time. The segregationist Capital Citizens Council threatened a boycott of the large Jewish-owned department stores, demanding that they cease advertising in the pro-desegregation newspaper the Arkansas Gazette. Jewish high school students encountered pressure from white, non-Jewish peers to oppose integration. These and other incidents persuaded many Little Rock Jews to adopt a policy of self-censorship on civil rights issues.

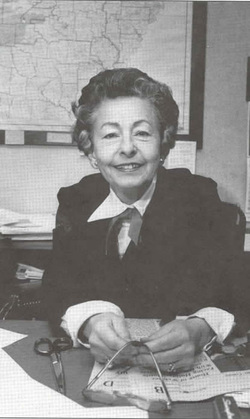

Irene Samuel

Irene Samuel

Despite the risks, Jewish women played important roles in the push to desegregate Little Rock Schools. Authorized by the state legislature, Governor Faubus forced the closure of the city’s four high schools rather than allow integration to proceed. In response, an all-white organization known as the Women’s Emergency Committee to Open Our Schools (WEC) formed to advocate for the re-opening of schools. The membership of the organization swelled to over sixteen hundred, including much of the Jewish community. Irene Samuel, the executive secretary, was not Jewish herself, but was married to a local Jewish physician and raised both her children as active participants of B’nai Israel. Many temple members followed her example; Josephine Menkus, president of the local chapter of National Council of Jewish Women, teamed up with Irene to direct WEC propaganda efforts. Jane Mendel operated the group’s secret phone tree list, which could disseminate important news to its large membership in a short period of time.

1957 and 1958 had also seen a spate of bombings and attempted bombings at Jewish sites across (and outside) the South, and both Little Rock synagogues received threats. Rabbi Irwin Groner of Agudath Achim, who served there from 1955 to 1959, had joined Rabbi Sanders in publicly supporting desegregation, and they were among a small minority of white clergy who did so. The rabbis received letters in October 1958 that warned of an impending bombing, but neither congregation canceled services. According to Rabbi Groner, synagogue attendance actually increased in the wake of the threats.

While the immediate educational crisis passed with the resumption of public, desegregated school in fall 1959, questions of Black equality did not disappear. Downtown businesses, including Jewish-owned department stores, continued to maintain segregation both in the roles afforded to Black and white employees and at their in-store eateries. In March 1960 protestors launched a series of sit-ins and pickets aimed at integrating department store restaurants, including the Gus Blass Company tearoom and the lunch counter at Pfeifer’s. Sam Strauss, president of Pfeifer’s, opted to remove all of the seats at the lunch counter rather than integrate. The 1960 sit-in wave ultimately failed, but activists successfully negotiated an end to segregation in downtown retail spaces by the beginning of 1963.

1957 and 1958 had also seen a spate of bombings and attempted bombings at Jewish sites across (and outside) the South, and both Little Rock synagogues received threats. Rabbi Irwin Groner of Agudath Achim, who served there from 1955 to 1959, had joined Rabbi Sanders in publicly supporting desegregation, and they were among a small minority of white clergy who did so. The rabbis received letters in October 1958 that warned of an impending bombing, but neither congregation canceled services. According to Rabbi Groner, synagogue attendance actually increased in the wake of the threats.

While the immediate educational crisis passed with the resumption of public, desegregated school in fall 1959, questions of Black equality did not disappear. Downtown businesses, including Jewish-owned department stores, continued to maintain segregation both in the roles afforded to Black and white employees and at their in-store eateries. In March 1960 protestors launched a series of sit-ins and pickets aimed at integrating department store restaurants, including the Gus Blass Company tearoom and the lunch counter at Pfeifer’s. Sam Strauss, president of Pfeifer’s, opted to remove all of the seats at the lunch counter rather than integrate. The 1960 sit-in wave ultimately failed, but activists successfully negotiated an end to segregation in downtown retail spaces by the beginning of 1963.

A Changing City and the Late 20th Century

By the time that Agudath Achim built its new synagogue in 1952, an outmigration from central neighborhoods to more suburban areas had already begun. Business patterns also changed, as new shopping centers drew customers away from downtown stores. Just thirteen years after dedicating its synagogue, Agudath Achim purchased a second property some five miles west of downtown. In 1973 they sold the downtown building and installed a modular unit on the new property, which they used until 1976, when they dedicated their new sanctuary.

Rabbi Sanders led B’nai Israel until his retirement in 1963, although he did remain in Little Rock and enjoyed the title of rabbi emeritus until his death in 1985. Rabbi Elijah Palnick replaced Rabbi Sanders and continued Rabbi Sanders’ legacy of progressive civic leadership. Like Agudath Achim, B’nai Israel chose to move to west Little Rock in the 1970s. The congregation preserved some furnishings for the new building and used edifice stones from their prior synagogue in the new construction of a more spacious, updated building.

As Little Rock’s Jewish congregations left downtown, so too did a number of Jewish businesses. Pfeifers of Arkansas sold their Little Rock stores and Hot Springs location to the Brown-Dunkin Co. (owners of Dillard’s) in 1963, and the Gus Blass Company followed suit in 1964. The stores merged and eventually closed their downtown locations. The Breier’s restaurant moved to a suburban shopping center in the late 1960s. As in other parts of the country, the rise of large retail chains and discount stores combined with new professional opportunities for younger generations to decrease the number of Jewish retail merchants.

Jewish practice also changed during the latter half of the 20th century. Agudath Achim had hired Conservative rabbis for some time but maintained Orthodox traditions, including separate seating for men and women, until the congregation moved to its new location in 1976. The congregation did adopt mixed-gender seating and left the Orthodox Union. They did not immediately adopt Conservative Movement practices, however, and the congregation remained unaffiliated until the early 21st century. A more strictly Orthodox option has existed in Little Rock since the early 1990s, when Rabbi Pinchus and Eshter Hadassah Climent established Lubavitch of Arkansas, a branch of the Chabad-Lubavitch emissary program.

Among notable Jewish residents in Little Rock, Annebelle Davis Clinton Imber Tuck stands out for her statewide electoral successes. An Arkansas native who spent part of her childhood in Bolivia and Brazil, she served as a criminal, chancery, and probate judge before winning election to the Arkansas Supreme Court in 1996. Her legal career included significant decisions that reformed school funding and struck down laws that criminalized homosexual activity. She was reelected to the court on two occasions and retired in 2010. As of 2023 she is the president of B’nai Israel.

Rabbi Sanders led B’nai Israel until his retirement in 1963, although he did remain in Little Rock and enjoyed the title of rabbi emeritus until his death in 1985. Rabbi Elijah Palnick replaced Rabbi Sanders and continued Rabbi Sanders’ legacy of progressive civic leadership. Like Agudath Achim, B’nai Israel chose to move to west Little Rock in the 1970s. The congregation preserved some furnishings for the new building and used edifice stones from their prior synagogue in the new construction of a more spacious, updated building.

As Little Rock’s Jewish congregations left downtown, so too did a number of Jewish businesses. Pfeifers of Arkansas sold their Little Rock stores and Hot Springs location to the Brown-Dunkin Co. (owners of Dillard’s) in 1963, and the Gus Blass Company followed suit in 1964. The stores merged and eventually closed their downtown locations. The Breier’s restaurant moved to a suburban shopping center in the late 1960s. As in other parts of the country, the rise of large retail chains and discount stores combined with new professional opportunities for younger generations to decrease the number of Jewish retail merchants.

Jewish practice also changed during the latter half of the 20th century. Agudath Achim had hired Conservative rabbis for some time but maintained Orthodox traditions, including separate seating for men and women, until the congregation moved to its new location in 1976. The congregation did adopt mixed-gender seating and left the Orthodox Union. They did not immediately adopt Conservative Movement practices, however, and the congregation remained unaffiliated until the early 21st century. A more strictly Orthodox option has existed in Little Rock since the early 1990s, when Rabbi Pinchus and Eshter Hadassah Climent established Lubavitch of Arkansas, a branch of the Chabad-Lubavitch emissary program.

Among notable Jewish residents in Little Rock, Annebelle Davis Clinton Imber Tuck stands out for her statewide electoral successes. An Arkansas native who spent part of her childhood in Bolivia and Brazil, she served as a criminal, chancery, and probate judge before winning election to the Arkansas Supreme Court in 1996. Her legal career included significant decisions that reformed school funding and struck down laws that criminalized homosexual activity. She was reelected to the court on two occasions and retired in 2010. As of 2023 she is the president of B’nai Israel.

The 21st Century

While many Arkansas towns saw their Jewish institutions decline and close during the late 20th and early 21st centuries, Jewish life in Little Rock remained relatively stable. Congregation Agudath Achim celebrated its centennial in 2005 with participation by Congressman Vic Snyder, the rabbis of B’nai Israel and Chabad Lubavitch of Little Rock, and the synagogue’s own Rabbi Martin Applebaum. The congregation claimed about 75 member households at that time, some of whom also belonged to B’nai Israel. Congregation Agudath Achim remained unaffiliated with a national movement at the time of its centennial but later joined the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism.

In the early 2020s, Little Rock remained home to an estimated 1,500 Jewish individuals, perhaps three quarters of Arkansas’s total Jewish population. Congregation Agudath Achim boasts approximately 100 member households, and B’nai Israel claims more than 300, with some overlap between the two. Both congregations employ full time rabbis and maintain active calendars, as does the local Chabad-Lubavitch center.

In the early 2020s, Little Rock remained home to an estimated 1,500 Jewish individuals, perhaps three quarters of Arkansas’s total Jewish population. Congregation Agudath Achim boasts approximately 100 member households, and B’nai Israel claims more than 300, with some overlap between the two. Both congregations employ full time rabbis and maintain active calendars, as does the local Chabad-Lubavitch center.

Updated March 2024.