Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Macon, Georgia

Macon: Historical Overview

|

In 1806, Secretary of War Henry Dearborn received a letter from President Thomas Jefferson indicating that the base formerly known as Fort Wilkinson (Milledgeville) was to be moved to Fort Hawkins, a frontier outpost located on Creek Indian land. After the U.S. Army defeated the Creek Nation in 1814, white settlers poured into the area eager to plant the new cash crop of the Deep South, cotton. The new planter class also imported a large workforce of enslaved African Americans. In 1821, Macon, named for a U.S. Senator from North Carolina, was incorporated and the neighboring farmland was distributed by lottery. By 1833, over 3,000 people lived in Macon, which had become a commercial center for the region with planters from across rural central Georgia traveling to the burgeoning town to do business.

|

Stories of the Jewish Community in Macon

Early Settlers

Macon’s role as a trading center also attracted Jewish merchants to the growing seat of Bibb County. The first Jew to settle in Macon was Nathan Grossmayer, who opened a store there in 1840; he later opened another store in Americus, Georgia. A handful of other Jews moved to the area in the early 1840s. In 1844, two young Jewish brothers by the name of Bettman passed away, one in Hawkinsville and the other in Perry. In response, Macon’s small Jewish community purchased a plot of land in Macon’s newly established Rose Hill Cemetery and the German-born brothers were buried there. This cemetery was used by Macon’s Jewish community for the next 35 years.

Macon’s role as a trading center also attracted Jewish merchants to the growing seat of Bibb County. The first Jew to settle in Macon was Nathan Grossmayer, who opened a store there in 1840; he later opened another store in Americus, Georgia. A handful of other Jews moved to the area in the early 1840s. In 1844, two young Jewish brothers by the name of Bettman passed away, one in Hawkinsville and the other in Perry. In response, Macon’s small Jewish community purchased a plot of land in Macon’s newly established Rose Hill Cemetery and the German-born brothers were buried there. This cemetery was used by Macon’s Jewish community for the next 35 years.

Beth Israel's first synagogue

Beth Israel's first synagogue

A Congregation Forms

Acquiring a burial ground was the first priority of the fledgling Jewish community. It would be another fifteen years before Macon Jews formally established a congregation. Eleven men called together “the Israelitish community” on October 30, 1859, at the home of Emanuel Brown to discuss the possibility of forming a congregation. A week later at the home of Elias Einstein, 28 men bound themselves to maintain and support a permanent congregation to be known as the House of Israel, Kahal Kodosh Beth Israel. They agreed to follow the German Orthodox minhag (ritual) and to hold services in Hebrew and German with lectures in German and English. Thus, even though the congregation was traditional, it incorporated elements of Reform Judaism through these lectures. Elias Einstein was elected the first president and appointed a committee to prepare a constitution, which was adopted on December 4, 1859; ten days later the Georgia legislature granted a charter to the congregation. There were 78 charter members, which likely means that some form of group worship had taken place prior to the formal organization of the congregation.

Beth Israel bought a sefer Torah for $110 and first met in a renovated rented room above a confectionery shop. Since the congregation was already fairly large, they were able to hire the services of a rabbi, Henry Lowenthal. Originally from London, Lowenthal had been serving a congregation in New Haven, Connecticut. Upon his arrival in Macon, he consecrated the rented room, placed the Torah in the ark, and began to hold regular services in both English and Hebrew. Before his first year was completed, Rabbi Lowenthal’s wife passed away, and the rabbi returned to England.

Acquiring a burial ground was the first priority of the fledgling Jewish community. It would be another fifteen years before Macon Jews formally established a congregation. Eleven men called together “the Israelitish community” on October 30, 1859, at the home of Emanuel Brown to discuss the possibility of forming a congregation. A week later at the home of Elias Einstein, 28 men bound themselves to maintain and support a permanent congregation to be known as the House of Israel, Kahal Kodosh Beth Israel. They agreed to follow the German Orthodox minhag (ritual) and to hold services in Hebrew and German with lectures in German and English. Thus, even though the congregation was traditional, it incorporated elements of Reform Judaism through these lectures. Elias Einstein was elected the first president and appointed a committee to prepare a constitution, which was adopted on December 4, 1859; ten days later the Georgia legislature granted a charter to the congregation. There were 78 charter members, which likely means that some form of group worship had taken place prior to the formal organization of the congregation.

Beth Israel bought a sefer Torah for $110 and first met in a renovated rented room above a confectionery shop. Since the congregation was already fairly large, they were able to hire the services of a rabbi, Henry Lowenthal. Originally from London, Lowenthal had been serving a congregation in New Haven, Connecticut. Upon his arrival in Macon, he consecrated the rented room, placed the Torah in the ark, and began to hold regular services in both English and Hebrew. Before his first year was completed, Rabbi Lowenthal’s wife passed away, and the rabbi returned to England.

The Civil War

Once the Civil War began in 1861, white Maconites of all faiths, including Jews, were called to serve the South. Some German immigrants living in the city organized the German Artillery Company and many young men of Congregation Beth Israel drilled regularly with the group. Among them was Bernhart Nordlinger, an Alsatian immigrant who had owned a store with his younger brother Wolfe in Macon before the war. Bernhart had taken over the position of chazzan, a person trained to lead songful prayer, after the rabbi had left the congregation.

Once the Civil War began in 1861, white Maconites of all faiths, including Jews, were called to serve the South. Some German immigrants living in the city organized the German Artillery Company and many young men of Congregation Beth Israel drilled regularly with the group. Among them was Bernhart Nordlinger, an Alsatian immigrant who had owned a store with his younger brother Wolfe in Macon before the war. Bernhart had taken over the position of chazzan, a person trained to lead songful prayer, after the rabbi had left the congregation.

Beth Israel Finds Its Way

After the Civil War, a growing number of Jews settled in Macon; by 1866, 20 new members were added to the temple’s membership. In 1869, a religious school was established with a trilingual curriculum in English, German, and Hebrew, and the Beth Israel board began to have regular meetings. That same year, a lot was purchased in an area that would later become the center of town upon which their synagogue would be built. Members of the congregation pledged up to 50 dollars each and, with additional funds from people outside of Macon, they were able to begin construction. In 1879, Beth Israel established a new Jewish cemetery on land donated by William Wolff; the new burial ground was named in Wolff’s honor.

The construction of the synagogue brought differences in religious practices to the forefront. When a pipe organ was installed in the sanctuary, Mark Isaacs, one of the affluent members of Beth Israel, threatened to withdraw his pledge to the building fund because the “faith of the Fathers had been dishonored” by this musical symbol of Reform Judaism. Traditionally, playing musical instruments is prohibited on the Sabbath. Issacs later returned to London, but he was not the only member who did not like the congregation’s movement toward Reform. Others set up a separate Congregation B’Nai Israel and purchased a separate burial ground in the city cemetery. Though this splinter congregation did not survive, their plot in the cemetery still exists today and contains 11 marked graves and eight unmarked graves. It was apparently abandoned with the arrival of the Eastern European Jews who established a new burial ground and the more religiously Orthodox congregation, Sherah Israel.

Beth Israel continued to debate how much to reform their religious practices. In 1869, a member proposed the first ritual reform, suggesting that the Reform worship style of Temple Emanu-El of New York be introduced, but the motion lost. In 1872, the congregation considered but did not adopt the Minhag Jastrow, which sought to balance both innovation and tradition. Two years later, there was a motion to affiliate with the newly formed Union of American Hebrew Congregations, but that lost as well. Still, the Jews of Beth Israel felt the impact of the American Reform movement. When the first class of Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise’s Hebrew Union College graduated, the temple sent a letter requesting one of these newly trained rabbis who were taught to conduct services in the language of the new land and to lecture, rather than chant. They began calling their rabbi “minister” and established the confirmation ritual for their religious school students.

In 1880, Beth Israel finally joined the Reform Union of American Hebrew Congregations and, just a few years later, decided that men no longer had to wear hats during services. Incidentally, the congregation had to resign from the UAHC in just two years after they had joined because of financial problems. In spite of the continued change, there were some in Macon who sought to limit these reforms. When, in 1891, certain Jewish communities discussed the possible changing of the Sabbath—from Saturday to Sunday—Jews in Macon spoke out against the idea, claiming that such a change would go against tradition.

After the Civil War, a growing number of Jews settled in Macon; by 1866, 20 new members were added to the temple’s membership. In 1869, a religious school was established with a trilingual curriculum in English, German, and Hebrew, and the Beth Israel board began to have regular meetings. That same year, a lot was purchased in an area that would later become the center of town upon which their synagogue would be built. Members of the congregation pledged up to 50 dollars each and, with additional funds from people outside of Macon, they were able to begin construction. In 1879, Beth Israel established a new Jewish cemetery on land donated by William Wolff; the new burial ground was named in Wolff’s honor.

The construction of the synagogue brought differences in religious practices to the forefront. When a pipe organ was installed in the sanctuary, Mark Isaacs, one of the affluent members of Beth Israel, threatened to withdraw his pledge to the building fund because the “faith of the Fathers had been dishonored” by this musical symbol of Reform Judaism. Traditionally, playing musical instruments is prohibited on the Sabbath. Issacs later returned to London, but he was not the only member who did not like the congregation’s movement toward Reform. Others set up a separate Congregation B’Nai Israel and purchased a separate burial ground in the city cemetery. Though this splinter congregation did not survive, their plot in the cemetery still exists today and contains 11 marked graves and eight unmarked graves. It was apparently abandoned with the arrival of the Eastern European Jews who established a new burial ground and the more religiously Orthodox congregation, Sherah Israel.

Beth Israel continued to debate how much to reform their religious practices. In 1869, a member proposed the first ritual reform, suggesting that the Reform worship style of Temple Emanu-El of New York be introduced, but the motion lost. In 1872, the congregation considered but did not adopt the Minhag Jastrow, which sought to balance both innovation and tradition. Two years later, there was a motion to affiliate with the newly formed Union of American Hebrew Congregations, but that lost as well. Still, the Jews of Beth Israel felt the impact of the American Reform movement. When the first class of Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise’s Hebrew Union College graduated, the temple sent a letter requesting one of these newly trained rabbis who were taught to conduct services in the language of the new land and to lecture, rather than chant. They began calling their rabbi “minister” and established the confirmation ritual for their religious school students.

In 1880, Beth Israel finally joined the Reform Union of American Hebrew Congregations and, just a few years later, decided that men no longer had to wear hats during services. Incidentally, the congregation had to resign from the UAHC in just two years after they had joined because of financial problems. In spite of the continued change, there were some in Macon who sought to limit these reforms. When, in 1891, certain Jewish communities discussed the possible changing of the Sabbath—from Saturday to Sunday—Jews in Macon spoke out against the idea, claiming that such a change would go against tradition.

Rabbi Isaac Marcuson

Rabbi Isaac Marcuson

Rabbi Isaac E. Marcuson

In 1894, Beth Israel hired a rabbi who would come to influence Macon’s Jewish community for almost 50 years. Isaac E. Marcuson of Cincinnati had just graduated from Hebrew Union College and came to serve Macon’s Reform congregation. He stayed initially for nine years, but came back in 1920, serving until his death in 1952. He brought with him liberal reforms, such as the removal of the rabbi’s hat during services, the adoption of the Union Prayer Book, and re-affiliation with the UAHC.

Rabbi Marcuson was quickly recognized and accepted by the entire community. When the Spanish-American War erupted in 1898, the young rabbi served as civilian chaplain for the wounded soldiers encamped in Macon. He also was active on the board to save the Macon Library, organized a Boy Scout troop, and served on the Boy Scout Council for many years. The rabbi helped to pioneer the county welfare agency when he headed the Organized Service and was chairman of the Macon Chapter of the American Red Cross. Additionally, he presided over the Social Workers’ Club as well as District Grand Lodge No. 5 of B’nai B’rith. He often said that his most satisfying experience was his regular monthly visit to the State Hospital at Milledgeville, a practice that has been continued by his successors. Rabbi Marcuson also became well known throughout the entire Reform Jewish community through his 33 years of service as secretary of the Central Conference of American Rabbis. He not only edited the Conference Year Book for 30 years, but he collaborated on the revision of the prayer book as well.

In 1894, Beth Israel hired a rabbi who would come to influence Macon’s Jewish community for almost 50 years. Isaac E. Marcuson of Cincinnati had just graduated from Hebrew Union College and came to serve Macon’s Reform congregation. He stayed initially for nine years, but came back in 1920, serving until his death in 1952. He brought with him liberal reforms, such as the removal of the rabbi’s hat during services, the adoption of the Union Prayer Book, and re-affiliation with the UAHC.

Rabbi Marcuson was quickly recognized and accepted by the entire community. When the Spanish-American War erupted in 1898, the young rabbi served as civilian chaplain for the wounded soldiers encamped in Macon. He also was active on the board to save the Macon Library, organized a Boy Scout troop, and served on the Boy Scout Council for many years. The rabbi helped to pioneer the county welfare agency when he headed the Organized Service and was chairman of the Macon Chapter of the American Red Cross. Additionally, he presided over the Social Workers’ Club as well as District Grand Lodge No. 5 of B’nai B’rith. He often said that his most satisfying experience was his regular monthly visit to the State Hospital at Milledgeville, a practice that has been continued by his successors. Rabbi Marcuson also became well known throughout the entire Reform Jewish community through his 33 years of service as secretary of the Central Conference of American Rabbis. He not only edited the Conference Year Book for 30 years, but he collaborated on the revision of the prayer book as well.

Macon Hospital

Macon Hospital

Civic Engagement

Rabbi Marcuson’s civic involvement mirrored that of his congregants as Macon Jews moved quickly to become part of the larger society. Macon Jews helped to establish and equip the Macon Hospital, now known as the Medical Center of Central Georgia. Others served on the Board of Trade that created municipal ownership of the water system, paved the streets, and installed sewers. Even as far back as 1884, Jews served on successive city councils, became charter members and officers of civic clubs, and were active in politics and civic affairs. Jewish women even sat on the board of Macon’s first organized charity, the non-denominational King’s Daughters.

A New Home for Beth Israel

Beth Israel soon faced problems with its synagogue. Across the street from the sanctuary, a farmers’ market had grown up. Wagons loaded with produce converged there on Saturdays; watermelon rinds began piling up on the Temple steps. It was not possible to keep the windows of the un-air conditioned synagogue closed and the noise became unbearable, especially on the Sabbath. Finally, it was decided that they should move and, on June 14, 1901, the congregation attended the final services in the old building, which was subsequently razed.

Rabbi Marcuson’s civic involvement mirrored that of his congregants as Macon Jews moved quickly to become part of the larger society. Macon Jews helped to establish and equip the Macon Hospital, now known as the Medical Center of Central Georgia. Others served on the Board of Trade that created municipal ownership of the water system, paved the streets, and installed sewers. Even as far back as 1884, Jews served on successive city councils, became charter members and officers of civic clubs, and were active in politics and civic affairs. Jewish women even sat on the board of Macon’s first organized charity, the non-denominational King’s Daughters.

A New Home for Beth Israel

Beth Israel soon faced problems with its synagogue. Across the street from the sanctuary, a farmers’ market had grown up. Wagons loaded with produce converged there on Saturdays; watermelon rinds began piling up on the Temple steps. It was not possible to keep the windows of the un-air conditioned synagogue closed and the noise became unbearable, especially on the Sabbath. Finally, it was decided that they should move and, on June 14, 1901, the congregation attended the final services in the old building, which was subsequently razed.

Current home of Beth Israel, built in 1902.

Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler.

Current home of Beth Israel, built in 1902.

Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler.

Congregation Beth Israel bought new property, but was temporarily without a building. Until the new temple was build, Jews worshiped at the First Baptist Church, whose own congregants had enjoyed Beth Israel’s hospitality when its church house had burned down in 1883. To honor this kindness, the pastor of First Baptist, Rev. J.L. White, helped lay the cornerstone of the new temple, along with Judge Max Meyerhardt, the Grand Master of the Georgia Grand Lodge of Masons, and Rabbi Marcuson at the dedication on October 30, 1901. The names of the members of the building committee, including congregational president Gustav Bernd, Jr., were inscribed on the cornerstone. The new temple was formally dedicated on September 19, 1902

When the constitution and bylaws were published in 1903, Congregation Beth Israel had approximately 89 member families. Of those, more than 75% had emigrated from or had parents who emigrated from Germany. Most of them were also merchants of some kind, dealing either in dry goods, clothing, or shoes.

When the constitution and bylaws were published in 1903, Congregation Beth Israel had approximately 89 member families. Of those, more than 75% had emigrated from or had parents who emigrated from Germany. Most of them were also merchants of some kind, dealing either in dry goods, clothing, or shoes.

Sherah Israel Sunday School 1923

Sherah Israel Sunday School 1923

Congregation Sherah Israel

While the late 19th and early 20th century wave of Eastern European Jewish immigrants settled primarily in the cities of the northeast, a small number came to Macon. The earliest record of this new group of immigrants arriving was in 1881. They were tradesmen of all kinds, including tinners, tailors, and trunk makers. When a group of 30 Jewish immigrants arrived in town, they were greeted by members of Temple Beth Israel and were permitted to stay temporarily in the vestry room of the synagogue until other accommodations could be made.

Many of the recent emigrants from Eastern Europe had their own ideas about practicing Judaism. In 1898, they established a burial society, “The Hebrew Aid Society,” and purchased land in Rose Hill. The first burial took place in 1904 with the death of Charlie Landers. They then decided to establish their own more traditional synagogue. On November 10, 1904, 54 men petitioned the Judge of Bibb Superior Court, W.H. Feldon, Jr., and were granted a charter incorporating Congregation Sherah Israel. At first, services were held in rented halls and then a larger two-story house, which was also home to the rabbi’s family. Rabbi Charles Glyck served the newly formed congregation intermittently until his death in 1923. Most of its members were recent immigrants. As late as 1940, the congregation still held adult education classes in Yiddish.

While the late 19th and early 20th century wave of Eastern European Jewish immigrants settled primarily in the cities of the northeast, a small number came to Macon. The earliest record of this new group of immigrants arriving was in 1881. They were tradesmen of all kinds, including tinners, tailors, and trunk makers. When a group of 30 Jewish immigrants arrived in town, they were greeted by members of Temple Beth Israel and were permitted to stay temporarily in the vestry room of the synagogue until other accommodations could be made.

Many of the recent emigrants from Eastern Europe had their own ideas about practicing Judaism. In 1898, they established a burial society, “The Hebrew Aid Society,” and purchased land in Rose Hill. The first burial took place in 1904 with the death of Charlie Landers. They then decided to establish their own more traditional synagogue. On November 10, 1904, 54 men petitioned the Judge of Bibb Superior Court, W.H. Feldon, Jr., and were granted a charter incorporating Congregation Sherah Israel. At first, services were held in rented halls and then a larger two-story house, which was also home to the rabbi’s family. Rabbi Charles Glyck served the newly formed congregation intermittently until his death in 1923. Most of its members were recent immigrants. As late as 1940, the congregation still held adult education classes in Yiddish.

Sherah Israel.

Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler

Sherah Israel.

Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler

Beth Israel in the Early 20th Century

Despite this new Orthodox congregation, Beth Israel continued to thrive. Rabbi Marcuson left Temple Beth Israel in 1903, but was replaced by Rabbi Louis Witt, who stayed only two years. The congregation next hired Rabbi Harry Weiss, of Butte, Montana, who showed a particular interest in the congregation’s children. Weiss developed the largest religious school attendance in the Temple’s 50-year history. Sliding walls had to be installed in the vestry to provide extra classrooms in order to accommodate the growing number of students.

The women of Temple Beth Israel played a large role in supporting and maintaining the congregation. Around the time of the semi-centennial in 1909, the Temple Guild and the Ladies’ Aid Society made contributions to the congregation. Beginning in 1917, the Ladies’ Aid Society began calling themselves “Sisterhood” and became the strong right arm of the congregation. Since then, they have assisted in funding a variety of improvements, including tables and cloths, electrical appliances, a furnace, Sunday School equipment, carpeting for the sanctuary, a new organ, and even a bible for the altar.

The IRO and Macon

By 1909, the Macon Jewish community was thriving. According to a survey taken by the Industrial Removal Office, there were approximately 470 Jews (110 families) living in Macon at the time. Along with the two congregations, there was also a local chapter of B’nai B’rith and a Progress Club. The community included at least one doctor and one lawyer, as well as a saddle manufacturer, a tannery, various merchants, small traders, peddlers, and working men. A few Jews were also cotton farmers. The IRO report declared that it was a “fine city for Hebrew gentlemen,” especially since they had kosher meat available in the city. In March of 1913, the Industrial Removal Office officially set up a committee in Macon to help new immigrants find work.

A number of Jewish immigrants in New York were sent to Macon through the IRO. One such immigrant was Philip Fierman, who arrived in Macon in early 1910. A Mr. Kaplan gave him work as a shoemaker and, in a letter Fierman wrote, he stated that his “own relatives could not have treated [him] better.” By 1920, he was still living in Macon, still working as a shoemaker, and had a wife and five children. Others sent to Macon through the IRO were not as fortunate. Mark Wallerstein was a good worker, but he was not able to find a job in Macon and was sent to St. Louis in 1904.

Despite this new Orthodox congregation, Beth Israel continued to thrive. Rabbi Marcuson left Temple Beth Israel in 1903, but was replaced by Rabbi Louis Witt, who stayed only two years. The congregation next hired Rabbi Harry Weiss, of Butte, Montana, who showed a particular interest in the congregation’s children. Weiss developed the largest religious school attendance in the Temple’s 50-year history. Sliding walls had to be installed in the vestry to provide extra classrooms in order to accommodate the growing number of students.

The women of Temple Beth Israel played a large role in supporting and maintaining the congregation. Around the time of the semi-centennial in 1909, the Temple Guild and the Ladies’ Aid Society made contributions to the congregation. Beginning in 1917, the Ladies’ Aid Society began calling themselves “Sisterhood” and became the strong right arm of the congregation. Since then, they have assisted in funding a variety of improvements, including tables and cloths, electrical appliances, a furnace, Sunday School equipment, carpeting for the sanctuary, a new organ, and even a bible for the altar.

The IRO and Macon

By 1909, the Macon Jewish community was thriving. According to a survey taken by the Industrial Removal Office, there were approximately 470 Jews (110 families) living in Macon at the time. Along with the two congregations, there was also a local chapter of B’nai B’rith and a Progress Club. The community included at least one doctor and one lawyer, as well as a saddle manufacturer, a tannery, various merchants, small traders, peddlers, and working men. A few Jews were also cotton farmers. The IRO report declared that it was a “fine city for Hebrew gentlemen,” especially since they had kosher meat available in the city. In March of 1913, the Industrial Removal Office officially set up a committee in Macon to help new immigrants find work.

A number of Jewish immigrants in New York were sent to Macon through the IRO. One such immigrant was Philip Fierman, who arrived in Macon in early 1910. A Mr. Kaplan gave him work as a shoemaker and, in a letter Fierman wrote, he stated that his “own relatives could not have treated [him] better.” By 1920, he was still living in Macon, still working as a shoemaker, and had a wife and five children. Others sent to Macon through the IRO were not as fortunate. Mark Wallerstein was a good worker, but he was not able to find a job in Macon and was sent to St. Louis in 1904.

The Bernd Family

The local IRO committee was led by Gustav Bernd, one of the most prominent Jews in Macon. The first Gustav Bernd in Macon made saddles and reins for the Confederate Army cavalry when he lived in Americus, Georgia. Following the surrender of General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox Court House in 1865, Bernd moved to Macon where, in addition to making horse goods, he began buying and selling hides and skins with his brother. They called the company A.& G. Bernd Co and worked together for a while. Eventually, the brothers parted ways and Gustav went into business with a Mr. Kent. In 1889, Kent left and Gustav II, the nephew of the founder, joined the firm. In 1937, Gus Bernd Kaufman, the man who would become the Jewish historian of Macon, entered the firm. Laurence Bernd, the company president at the time, died in 1943 and Gus Kaufman took over. He would remain in that position for the next 37 years, the longest reign in the family.

G. Bernd Co. had its height between the Civil War and World War I. At that time, it ran the largest harness factory in the southeast. Yet, the invention of the automobile drastically decreased the demand for saddles and harnesses and, by 1922, the company no longer manufactured those goods. During World War II, the company diversified and began handling all byproducts of the meat-packing industry including tallow, bone scraps, and meat scraps. Tallow was sold to soap manufacturers and then detergent makers. Later, it went to feed mills to be used in hog, cattle, and chicken feed. Eventually, the company ceased dealing with byproducts and devoted all its operations to the hide business. In 1981, owner-president Gus Bernd Kaufman retired and sold Macon’s oldest family-owned company, ending a 115-year tradition.

World War I

When America entered World War I, Macon Jews performed their civic duty. Rabbi Weiss conducted services at Camp Wheeler, the local army base, and Congregation Beth Israel provided religious services and home hospitality for Jewish soldiers. Members of both Beth Israel and Sherah Israel served in the armed forces. Even before the United States was officially involved in the war, Jews in Macon raised money for Jewish War Relief, an organization that helped victims of the destruction. In 1917, Macon was made the state headquarters for the Jewish National Congress and delegates from the state traveled to Washington D.C. to participate in the debates concerning the refugees in Europe and a proposed Jewish state in Palestine.

The local IRO committee was led by Gustav Bernd, one of the most prominent Jews in Macon. The first Gustav Bernd in Macon made saddles and reins for the Confederate Army cavalry when he lived in Americus, Georgia. Following the surrender of General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox Court House in 1865, Bernd moved to Macon where, in addition to making horse goods, he began buying and selling hides and skins with his brother. They called the company A.& G. Bernd Co and worked together for a while. Eventually, the brothers parted ways and Gustav went into business with a Mr. Kent. In 1889, Kent left and Gustav II, the nephew of the founder, joined the firm. In 1937, Gus Bernd Kaufman, the man who would become the Jewish historian of Macon, entered the firm. Laurence Bernd, the company president at the time, died in 1943 and Gus Kaufman took over. He would remain in that position for the next 37 years, the longest reign in the family.

G. Bernd Co. had its height between the Civil War and World War I. At that time, it ran the largest harness factory in the southeast. Yet, the invention of the automobile drastically decreased the demand for saddles and harnesses and, by 1922, the company no longer manufactured those goods. During World War II, the company diversified and began handling all byproducts of the meat-packing industry including tallow, bone scraps, and meat scraps. Tallow was sold to soap manufacturers and then detergent makers. Later, it went to feed mills to be used in hog, cattle, and chicken feed. Eventually, the company ceased dealing with byproducts and devoted all its operations to the hide business. In 1981, owner-president Gus Bernd Kaufman retired and sold Macon’s oldest family-owned company, ending a 115-year tradition.

World War I

When America entered World War I, Macon Jews performed their civic duty. Rabbi Weiss conducted services at Camp Wheeler, the local army base, and Congregation Beth Israel provided religious services and home hospitality for Jewish soldiers. Members of both Beth Israel and Sherah Israel served in the armed forces. Even before the United States was officially involved in the war, Jews in Macon raised money for Jewish War Relief, an organization that helped victims of the destruction. In 1917, Macon was made the state headquarters for the Jewish National Congress and delegates from the state traveled to Washington D.C. to participate in the debates concerning the refugees in Europe and a proposed Jewish state in Palestine.

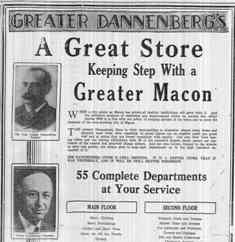

1929 ad for Dannenberg's

1929 ad for Dannenberg's

Between the World Wars

After the war, both of Macon’s Jewish congregations expanded. In 1919, Sherah Israel purchased land for a synagogue. The building was completed in 1922 and a dedication ceremony was held on June 4. That same year, the Ladies Auxiliary for Congregation Sherah Israel was officially formed at the home of Fannie Kaplan, with Annie Goldgar as the first president. In 1920, Rabbi Marcuson returned to Beth Israel. A new annex to the Temple, which had been postponed because of the war, was built and dedicated in honor of Gustav Bernd, the congregation’s president who had recently passed away. The next year, the Beth Israel Community Relations Committee was formed to deal with the problems of all Macon Jews. They invited the members of Sherah Israel to worship at Beth Israel while their synagogue was being built.

Soon after the war, Zionist organizations began forming in greater numbers. At the time, groups of Jews, including those in Macon, were meeting and advocating the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine. In spite of this growing movement, Rabbi Marcuson, who opposed the Zionist cause, wrote a letter to the Macon Weekly Telegraph denying the statement that the Jew is ‘a person without a country’ and declaring that “[w]e are going to stay in America and remain good American Jews.”

Even though the war was over, the Jewish War Relief organization continued to raise money for those Jews starving in Eastern Europe. Among the most generous contributors was Walter Dannenberg. Walter Dannenberg’s father, Joseph Dannenberg, emigrated from Germany in the 1850s, but did not arrive in Macon until after the Civil War. In 1867, Joseph started a wholesale dry goods store with Myer Nussbaum. In the 1880s, they split up and went into business separately. At that point, Joseph partnered up with W.A. Doody and the business became known as the Dannenberg Company.

At age 16, Joseph’s son, Walter, joined the company and he eventually added a retail business. The company became a leading wholesale enterprise while also became one of the first firms in the country to departmentalize its retail store. Dannenberg’s Department Store was one of the leading stores in Macon. It was on the front lines during the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.Walter Dannenberg served on the Committee of Businessmen and Black Clergy and helped bring about the peaceful integration of Macon stores. Dannenberg’s quietly took down the segregation signs in its stores without any official announcement and proceeded to integrate its lunch counter without incident. The Dannenberg Department store closed in 1965. At the time, it was the largest department store in the area, but had been hurt by the opening of the local mall. In order to compete, they would have had to renovate the store; instead, they decided to liquidate the business.

After the war, both of Macon’s Jewish congregations expanded. In 1919, Sherah Israel purchased land for a synagogue. The building was completed in 1922 and a dedication ceremony was held on June 4. That same year, the Ladies Auxiliary for Congregation Sherah Israel was officially formed at the home of Fannie Kaplan, with Annie Goldgar as the first president. In 1920, Rabbi Marcuson returned to Beth Israel. A new annex to the Temple, which had been postponed because of the war, was built and dedicated in honor of Gustav Bernd, the congregation’s president who had recently passed away. The next year, the Beth Israel Community Relations Committee was formed to deal with the problems of all Macon Jews. They invited the members of Sherah Israel to worship at Beth Israel while their synagogue was being built.

Soon after the war, Zionist organizations began forming in greater numbers. At the time, groups of Jews, including those in Macon, were meeting and advocating the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine. In spite of this growing movement, Rabbi Marcuson, who opposed the Zionist cause, wrote a letter to the Macon Weekly Telegraph denying the statement that the Jew is ‘a person without a country’ and declaring that “[w]e are going to stay in America and remain good American Jews.”

Even though the war was over, the Jewish War Relief organization continued to raise money for those Jews starving in Eastern Europe. Among the most generous contributors was Walter Dannenberg. Walter Dannenberg’s father, Joseph Dannenberg, emigrated from Germany in the 1850s, but did not arrive in Macon until after the Civil War. In 1867, Joseph started a wholesale dry goods store with Myer Nussbaum. In the 1880s, they split up and went into business separately. At that point, Joseph partnered up with W.A. Doody and the business became known as the Dannenberg Company.

At age 16, Joseph’s son, Walter, joined the company and he eventually added a retail business. The company became a leading wholesale enterprise while also became one of the first firms in the country to departmentalize its retail store. Dannenberg’s Department Store was one of the leading stores in Macon. It was on the front lines during the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.Walter Dannenberg served on the Committee of Businessmen and Black Clergy and helped bring about the peaceful integration of Macon stores. Dannenberg’s quietly took down the segregation signs in its stores without any official announcement and proceeded to integrate its lunch counter without incident. The Dannenberg Department store closed in 1965. At the time, it was the largest department store in the area, but had been hurt by the opening of the local mall. In order to compete, they would have had to renovate the store; instead, they decided to liquidate the business.

The Great Depression

While the treasury of Congregation Beth Israel was depleted during the Great Depression, the pews remained full. New members continued to join the congregation as the religious school flourished. As the decade wore on, some members were forced to drop out, but the Sisterhood and the Council of Jewish Women helped to keep the temple solvent. By 1933, the temple was even able to send a contribution to a synagogue in California that had been damaged by the earthquake.

World War II

The start of World War II reactivated Camp Wheeler in Macon and brought an Air Force Base to Cochran field as well as an Air Materiel Depot to Warner Robins. Rabbi Marcuson was appointed civilian chaplain and young men from both congregations fought in the war. Beth Israel’s Sisterhood helped out by throwing temple receptions and hosting camp social hours. Members of both congregations threw themselves into work with organization such as the USO, the Red Cross, and Bundles for Britain. Thousands of servicemen and women found a home away from home in the temple annex. The Passover seder held by the Sisterhood was met by such an overwhelming response that it eventually had to be held in the Shrine Mosque. The Ladies Auxiliary of Sherah Israel also held seders for servicemen.

After World War II

In 1947, Rabbi Charles Rubel came to Macon and served Sherah Israel for 11 years. He helped lead the congregation away from strict Orthodoxy. During his tenure, the congregation instituted its first confirmation ceremony, adopted a new Conservative prayer book, and affiliated with the United Synagogue of America, the national organization of Conservative Judaism. The congregation remained strongly Zionist and a celebration was held in honor of the United Nations’ decision to partition Palestine and create a Jewish state. The following year, a campaign to expand the building was launched under the guidance of congregational president, Sidney Backer. They bought and tore down two houses next to the synagogue to build an expansion. In 1953, Sherah Israel dedicated its new annex, which featured a large auditorium, five classrooms, a rabbi’s study, a library, and a kitchen. Sherah Israel paid off the mortgage on this addition within six years.

While the treasury of Congregation Beth Israel was depleted during the Great Depression, the pews remained full. New members continued to join the congregation as the religious school flourished. As the decade wore on, some members were forced to drop out, but the Sisterhood and the Council of Jewish Women helped to keep the temple solvent. By 1933, the temple was even able to send a contribution to a synagogue in California that had been damaged by the earthquake.

World War II

The start of World War II reactivated Camp Wheeler in Macon and brought an Air Force Base to Cochran field as well as an Air Materiel Depot to Warner Robins. Rabbi Marcuson was appointed civilian chaplain and young men from both congregations fought in the war. Beth Israel’s Sisterhood helped out by throwing temple receptions and hosting camp social hours. Members of both congregations threw themselves into work with organization such as the USO, the Red Cross, and Bundles for Britain. Thousands of servicemen and women found a home away from home in the temple annex. The Passover seder held by the Sisterhood was met by such an overwhelming response that it eventually had to be held in the Shrine Mosque. The Ladies Auxiliary of Sherah Israel also held seders for servicemen.

After World War II

In 1947, Rabbi Charles Rubel came to Macon and served Sherah Israel for 11 years. He helped lead the congregation away from strict Orthodoxy. During his tenure, the congregation instituted its first confirmation ceremony, adopted a new Conservative prayer book, and affiliated with the United Synagogue of America, the national organization of Conservative Judaism. The congregation remained strongly Zionist and a celebration was held in honor of the United Nations’ decision to partition Palestine and create a Jewish state. The following year, a campaign to expand the building was launched under the guidance of congregational president, Sidney Backer. They bought and tore down two houses next to the synagogue to build an expansion. In 1953, Sherah Israel dedicated its new annex, which featured a large auditorium, five classrooms, a rabbi’s study, a library, and a kitchen. Sherah Israel paid off the mortgage on this addition within six years.

Temple Israel Hannukah Party, 1948

Temple Israel Hannukah Party, 1948

The 1950s was a decade of transition at Beth Israel. On September 2, 1952, Rabbi Isaac Marcuson, who had spent over 40 years leading Beth Israel, died at his desk. Visiting rabbis, the president of the temple, and other members conducted services until Newton J. Friedman, of Cleveland, Ohio, was installed as rabbi the following year. In the fall of 1952, Temple Beth Israel launched a building fund campaign to enlarge the religious school. The new wing was dedicated two years later and coincided with the 95th anniversary of the congregation. In 1955, the constitution and bylaws were revised, granting wives the right to vote. In 1957, Rabbi Friedman resigned from Beth Israel and Harold L. Gelfman, originally from Springfield, Massachusetts, was hired to replace him. Rabbi Gelfman served Beth Israel until 1976.

During the decades after World War II, Sherah Israel experienced change as well, especially in the role of women in the congregation. In 1958, Mrs. Henry Koplin became the first woman elected to the Board of Governors. In 1960, much like Beth Israel five years earlier, Sherah Israel adopted a new constitution and bylaws that granted wives the right to vote within the congregation. In 1961, the congregation celebrated its first bat mitzvah. Ten years later, Beverly Kruger became the first woman to serve as an officer of the congregation. By 1974, they were counting women towards the minyan and allowing them to receive Torah honors on the bimah. In 1966, the religious school began teaching the Sephardic pronunciation of Hebrew, reflecting the congregation’s movement away from its Ashkenazic immigrant roots toward a Jewish identity in which Israel played a central role.

During the decades after World War II, Sherah Israel experienced change as well, especially in the role of women in the congregation. In 1958, Mrs. Henry Koplin became the first woman elected to the Board of Governors. In 1960, much like Beth Israel five years earlier, Sherah Israel adopted a new constitution and bylaws that granted wives the right to vote within the congregation. In 1961, the congregation celebrated its first bat mitzvah. Ten years later, Beverly Kruger became the first woman to serve as an officer of the congregation. By 1974, they were counting women towards the minyan and allowing them to receive Torah honors on the bimah. In 1966, the religious school began teaching the Sephardic pronunciation of Hebrew, reflecting the congregation’s movement away from its Ashkenazic immigrant roots toward a Jewish identity in which Israel played a central role.

The Jewish Community in Macon Today

Unlike many other Southern Jewish communities, Macon’s Jewish population has remained strong in the decades after World War II largely due to the local economy. The Jewish community of Macon went from 850 Jews in 1937 to 900 in 1980. The population seems to have plateaued in recent decades at around 1000 people, though it has likely declined a bit over the last decade or so. Originally a cotton based economy, Macon soon became a manufacturing center. With the coming of the interstate highways in the 1960s, the economic focus shifted from agriculture and industry to retail and service. Much of the local economy today is based around health care, the financial and insurance industries, and higher education. There are also numerous institutions of higher education, including Wesleyan College, which the first chartered women’s college, and Macon State College. Companies like the zipper manufacturer YKK Corporation of America and the insurance company GEICO, which built a large regional office in Macon, continue to draw people into the city. The Robins Air Force Base, located to the south in the city of Warner Robins, is also a major employer for the area. As in many other Southern cities, Macon’s Jewish population has moved away from retail trade into the professions.

Macon still has two strong Jewish congregations. Sherah Israel has periodically gone without a rabbi, though they hired Aaron Rubenstein to lead the congregation in 1993. In 1999, Congregation Sherah Israel decided to return to their community’s original name, Sha’arey Israel. Rabbi Rubenstein left the congregation in 2005 and was succeeded by Rabbi Rachel Tamar Bat-Or who served Congregation Sha’arey Israel until 2011. Beth Israel has shrunk slightly from its peak of 123 families in 1970 to 95 families in 2008, though the congregation is still active. In recent years, efforts have been made to establish partnerships between these two congregations. In 1993, a joint Chevra Kadisha (a Jewish burial society) was established between the two congregations and a new Macon Youth Group was formed to bring together the city’s Jewish youth into one organization. This work was continued in 1995 when a joint Sunday school was established for the Jewish youth of central Georgia. This joint school disbanded in 2003, and both congregations currently maintain their own religious schools.

The Jews of Macon have played an important role in the city's history, and remain a vibrant part of city life today.

Macon still has two strong Jewish congregations. Sherah Israel has periodically gone without a rabbi, though they hired Aaron Rubenstein to lead the congregation in 1993. In 1999, Congregation Sherah Israel decided to return to their community’s original name, Sha’arey Israel. Rabbi Rubenstein left the congregation in 2005 and was succeeded by Rabbi Rachel Tamar Bat-Or who served Congregation Sha’arey Israel until 2011. Beth Israel has shrunk slightly from its peak of 123 families in 1970 to 95 families in 2008, though the congregation is still active. In recent years, efforts have been made to establish partnerships between these two congregations. In 1993, a joint Chevra Kadisha (a Jewish burial society) was established between the two congregations and a new Macon Youth Group was formed to bring together the city’s Jewish youth into one organization. This work was continued in 1995 when a joint Sunday school was established for the Jewish youth of central Georgia. This joint school disbanded in 2003, and both congregations currently maintain their own religious schools.

The Jews of Macon have played an important role in the city's history, and remain a vibrant part of city life today.