Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Fort Smith, Arkansas

Historical Overview

Fort Smith sits at the border of western Arkansas and Oklahoma, and it serves (with Greenwood) as one of Sebastian County’s two seats. The city’s founding occurred in November 1817, when United States troops began constructing an outpost at Belle Point, a peninsula along the Arkansas River. The military established Fort Smith—named for General Thomas A. Smith—to manage relations between the Osage and Cherokee Nations living in the area. A small Euro-American settlement took shape around the fort within a few years.

Jewish settlers lived in Fort Smith as early as 1842. The earliest arrivals made their living primarily in trade, which included exchanges with nearby Indian nations. The Jewish population did not grow quickly at first, however, and a congregation did not form until 1880. The arrival of new Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe in the late 19th and early 20th century brought a larger Jewish presence to the city, and Jewish life remained strong through the mid-20th century. Fort Worth’s Jewish community is smaller in the early 21st century than it was at its peak, but the local synagogue, United Hebrew Congregation, still served approximately fifty members as of 2017.

Jewish settlers lived in Fort Smith as early as 1842. The earliest arrivals made their living primarily in trade, which included exchanges with nearby Indian nations. The Jewish population did not grow quickly at first, however, and a congregation did not form until 1880. The arrival of new Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe in the late 19th and early 20th century brought a larger Jewish presence to the city, and Jewish life remained strong through the mid-20th century. Fort Worth’s Jewish community is smaller in the early 21st century than it was at its peak, but the local synagogue, United Hebrew Congregation, still served approximately fifty members as of 2017.

Early Jewish Settlers

The civilian settlers who first made their way to Fort Smith engaged in trade with military personnel, local Indians, and a variety of frontier travelers. (The Osage Nation had long claimed the area as a hunting ground and held treaty rights to the land in the early 19th century, and members of the Cherokee and Choctaw nations had arrived more recently as a result of displacement and forced migration.) The “Indian trade” constituted a significant portion of local business: American Indians provided hides, crops, and other raw materials; cash or tribal scrip obtained through treaty payments; and sometimes manufactured goods to Euro-American traders in exchange for a variety of provisions and supplies shipped on the Arkansas River from points east.

Fort Smith’s earliest known Jewish settler was Edward Czarniknow, who immigrated from Posen—present day Poznań, Poland—in 1842. Known warmly as “General,” Czarnikow quickly established a thriving trade with the American Indian population in and around Fort Smith. He also became popular in the area; some of his American Indian trading partners reportedly named their children “Edward” after him. Czarnikow’s brother Louis soon followed, as did several other Jewish men, including Morris Price, Michael Charles, and Leopold Lowenthal.

Over the next two decades, Fort Smith became home to a handful of businesses that were either owned or managed by Jewish settlers. Newcomers included William Mayer and A. Cline in the 1850s and four Levy brothers by the time of the 1860 U.S. census. L., M., Julius, and Isaac Levy were all born in the German State of Württemberg and lived in a boarding house. The census lists L. Levy as a merchant and the others as Clerks. Another Levy family, that of William and Phillipina, lived in Fort Smith at that time, although they hailed from Hamburg.

Another notable Fort Smith pioneer was Jewish merchant Isaac Cohn, a German immigrant who settled at Fort Smith in the early 1870s after his store in Pine Bluff burned down. In Fort Smith, Cohn, like Czarnikow, established a strong relationship with the local Indigenous American community. This relationship made up the bulk of Cohn’s trading. Cohn was also close friends with a young Choctaw man named Green McCurtain, who went on to serve as Principal Chief of the Choctaw Nation in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Cohn invited several of his relatives from Europe to come work in his store, and one of them named Benno Stein even opened his own store in 1892 as well as a wholesale dry goods firm in 1901.

Fort Smith’s earliest known Jewish settler was Edward Czarniknow, who immigrated from Posen—present day Poznań, Poland—in 1842. Known warmly as “General,” Czarnikow quickly established a thriving trade with the American Indian population in and around Fort Smith. He also became popular in the area; some of his American Indian trading partners reportedly named their children “Edward” after him. Czarnikow’s brother Louis soon followed, as did several other Jewish men, including Morris Price, Michael Charles, and Leopold Lowenthal.

Over the next two decades, Fort Smith became home to a handful of businesses that were either owned or managed by Jewish settlers. Newcomers included William Mayer and A. Cline in the 1850s and four Levy brothers by the time of the 1860 U.S. census. L., M., Julius, and Isaac Levy were all born in the German State of Württemberg and lived in a boarding house. The census lists L. Levy as a merchant and the others as Clerks. Another Levy family, that of William and Phillipina, lived in Fort Smith at that time, although they hailed from Hamburg.

Another notable Fort Smith pioneer was Jewish merchant Isaac Cohn, a German immigrant who settled at Fort Smith in the early 1870s after his store in Pine Bluff burned down. In Fort Smith, Cohn, like Czarnikow, established a strong relationship with the local Indigenous American community. This relationship made up the bulk of Cohn’s trading. Cohn was also close friends with a young Choctaw man named Green McCurtain, who went on to serve as Principal Chief of the Choctaw Nation in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Cohn invited several of his relatives from Europe to come work in his store, and one of them named Benno Stein even opened his own store in 1892 as well as a wholesale dry goods firm in 1901.

Business and Civic Life

Over the next several decades more Jewish people immigrated to Fort Smith, generally from Eastern Europe, and as the city began to grow rapidly, Jewish immigrants quickly entered into a wide array of business and civil engagements. Mark Stuart Cohn (1849-1930), much like Isaac Cohn and Edward Czarniknow, was a notable merchant who primarily traded with the local Indigenous Americans, involving himself in multiple lines of trade that directly interacted with Indigenous Americans, such as cattle, cotton, and gravel. When the Frisco Railroad Company extended into Fort Smith, he established a short rail line to his quarry to supply the company with gravel. Cohn was also the owner of a handful of general merchandise stores and trading posts. One of his five sons, Sol C. Cohn (1877-1940) also began a career in trading with Indigenous Americans, but soon abandoned that venture to open a men’s clothing store.

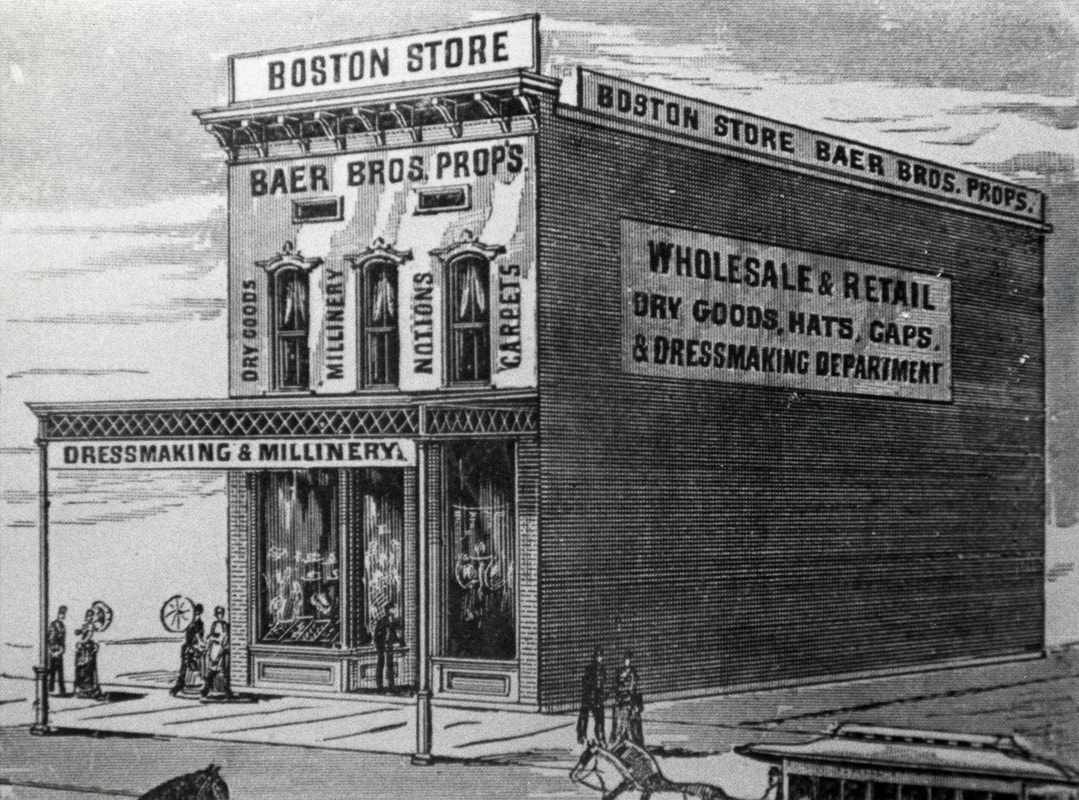

Another prominent Jewish business leader was Bernhard Baer (1836-1886), who returned to Fort Smith after leaving the Third Arkansas Regiment at the rank of officer in 1865. Upon his return, Baer opened a grocery store and established the National Bank of western Arkansas in 1871. Baer’s grocery business exceeded expectations, and by the 1880s spread over two hundred miles west and fifty miles out of Fort Smith in other directions, making over half a million dollars per year. Beginning in 1873 and continuing for several years, Baer served as a Fort Smith alderman. He was also an honored member of Fort Smith’s Masonic Lodge, and in 1889 the organization’s newly built temple was named for him. Baer went on to financially support his younger relatives Julius and Sigmund Baer, with Aaron Fuller, to establish the Boston Store, a grocery and dry goods store. Their Boston Store soon developed into one of the most successful Southwestern trade stores for the next century. The Baers together with the Fullers and financier C. A. Stix established the Stix, Baer, and Fuller firm, a department store whose name later changed to The Grand-Leader.

Around the mid-1890s, 118 Jewish business men and women were listed in Fort Smith’s city directory. These people lived and worked as attorneys, auctioneers, book binders, brokers, carpet and matting store owners, cigar manufacturers, china-glass-queensware sellers, commission merchants, dyers and scourers, grocers, livery stable owners, tailors, saloon keepers, meat market owners, printers, newspapermen, and dealers in hides, wool, and hardware. The Jewish population continued to grow steadily, and by 1900, the population of Fort Smith was about 20,000, with 230 people being Jews. One of the most notable Jewish businessmen in Fort Smith from the 20th century was Alvin Summerfield Tilles (1894-1978), a Fort Smith native who owned a women’s clothing store for over fifty years. The clothing store was originally owned by Alvin’s father and was named The Fair, but after his father’s death in 1923, Alvin took over the store, renaming it Tilles Inc. Tilles was also one of the first people from Fort Smith to enlist in WWI, leaving the army as a captain. A talented painter and photographer, Tilles was a supporter of the Fort Smith Art Center. He died at 84 in 1978. His estate helped establish several trusts which still continue to support educational, cultural, religious, and social service organizations in Arkansas.

Fort Smith was also home to several doctors and humanitarians who greatly helped expand access to medical care and civic aid in the city. Dr. Goldstein (1888-1980) was a graduate of Tulane University and the University of Tennessee Medical School who moved to Fort Smith in 1913 after studying dermatology in Vienna, London, and Philadelphia. He was a regimental surgeon for the US Army 328th Combat Infantry in WWI, and upon his return to Fort Smith following the war, Goldstein served as a founding member of the Cooper Clinic, a preventive medicine practice which was active in a large area of western Arkansas and eastern Oklahoma. Goldstein was also one of the organizers of the Sebastian County and Arkansas chapters of the American Cancer Society as well as holding free clinics in western Arkansas and serving as a medical advisor to small communities establishing hospitals. Another deeply influential Fort Smith resident was Rose (Sherman) Weinberger (1899-1986), who spent most of her life seeking to benefit the general public, especially focussing on civil rights. Weinberger served as the first Jewish member of the YWCA Board of Forth Smith, where she helped find work for young women and established a branch specifically for Black women as well as a nursery for Black children. Weinberger also worked with Dr. Charles Holt to establish the Twin City Hospital for Black people after learning that the other two hospitals in the city did not treat Black people. She also created a library for Black people at Lincoln High School, assisted in forming county and state Democratic women’s clubs, founded the Roger Bost School—a school for developmentally disabled children and adults—and worked with Governor Ben Laney to establish the Arkansas School of Nursing. Rose Weinberger received multiple awards for his civic and humanitarian efforts.

Around the mid-1890s, 118 Jewish business men and women were listed in Fort Smith’s city directory. These people lived and worked as attorneys, auctioneers, book binders, brokers, carpet and matting store owners, cigar manufacturers, china-glass-queensware sellers, commission merchants, dyers and scourers, grocers, livery stable owners, tailors, saloon keepers, meat market owners, printers, newspapermen, and dealers in hides, wool, and hardware. The Jewish population continued to grow steadily, and by 1900, the population of Fort Smith was about 20,000, with 230 people being Jews. One of the most notable Jewish businessmen in Fort Smith from the 20th century was Alvin Summerfield Tilles (1894-1978), a Fort Smith native who owned a women’s clothing store for over fifty years. The clothing store was originally owned by Alvin’s father and was named The Fair, but after his father’s death in 1923, Alvin took over the store, renaming it Tilles Inc. Tilles was also one of the first people from Fort Smith to enlist in WWI, leaving the army as a captain. A talented painter and photographer, Tilles was a supporter of the Fort Smith Art Center. He died at 84 in 1978. His estate helped establish several trusts which still continue to support educational, cultural, religious, and social service organizations in Arkansas.

Fort Smith was also home to several doctors and humanitarians who greatly helped expand access to medical care and civic aid in the city. Dr. Goldstein (1888-1980) was a graduate of Tulane University and the University of Tennessee Medical School who moved to Fort Smith in 1913 after studying dermatology in Vienna, London, and Philadelphia. He was a regimental surgeon for the US Army 328th Combat Infantry in WWI, and upon his return to Fort Smith following the war, Goldstein served as a founding member of the Cooper Clinic, a preventive medicine practice which was active in a large area of western Arkansas and eastern Oklahoma. Goldstein was also one of the organizers of the Sebastian County and Arkansas chapters of the American Cancer Society as well as holding free clinics in western Arkansas and serving as a medical advisor to small communities establishing hospitals. Another deeply influential Fort Smith resident was Rose (Sherman) Weinberger (1899-1986), who spent most of her life seeking to benefit the general public, especially focussing on civil rights. Weinberger served as the first Jewish member of the YWCA Board of Forth Smith, where she helped find work for young women and established a branch specifically for Black women as well as a nursery for Black children. Weinberger also worked with Dr. Charles Holt to establish the Twin City Hospital for Black people after learning that the other two hospitals in the city did not treat Black people. She also created a library for Black people at Lincoln High School, assisted in forming county and state Democratic women’s clubs, founded the Roger Bost School—a school for developmentally disabled children and adults—and worked with Governor Ben Laney to establish the Arkansas School of Nursing. Rose Weinberger received multiple awards for his civic and humanitarian efforts.

Organized Jewish Life

In addition to Jewish business and civil life, organized Jewish life in Fort Smith was vibrant and flourished for the better part of the 20th century. The origins of congregational life in Fort Smith trace back to the establishment of a Jewish Cemetery Association in 1871. Louis Tilles, Bernhard Baer, Joseph Adler, and Edward Czarnikow served as the cemetery’s founding officers. Rosalie Tilles (1837-1872) was the first known Jewish person to be buried in Fort Smith. The Hebrew Ladies Benevolent Society was founded the same year as the synagogue and changed its name to Temple Ladies’ Aid Society after the formation of a congregation. In 1878 the local B’nai B’rith Lodge was founded, becoming one of the most active Jewish groups in Fort Smith. At the start of the 20th century, the Lodge became deeply invested in aiding Jewish immigrants fleeing poverty and violence in Russia.

Fort Smith’s first Jewish congregation, Temple of Israel, was formed in 1880 under the leadership of President Simon Joel. A second Jewish congregation existed in the early 1880s, and in 1886 the two merged into one congregation, United Hebrew Congregation, with the aid of Rabbi Messing of St. Louis. Neither congregation owned its own building prior to the merger, and the combined congregation met in a retail building and held its first confirmation services at the Christian Church of Fort Smith. As a part of the new congregation, the Temple Ladies’ Aid Society focused on maintaining the choir and aiding the congregation generally. In 1892, United Hebrew Congregation built their own synagogue on the corner of Eleventh and E Streets. The congregation’s second confirmation service was held in the new synagogue, and the congregation owned three Torah scrolls at the time of its dedication.

As United Hebrew Congregation constructed its first permanent home, it also hired its first rabbi, Dr. Abe Traugott, who served the congregation from1892 to 1896. In the thirteen years after Rabbi Traugott’s departure, the congregation doubled in size from 41 to over 80 members. In 1907, Rabbi Edward S. Levy joined United Hebrew Congregation as spiritual leader. He stayed with the congregation until his death in 1914. Rabbi Charles Latz occupied the pulpit after Rabbi Levy’s death and became known for his civic work; he was president of a War Prison Council organized in 1919 and deeply involved in the Fort Smith public library. Additionally, Latz served as a circuit rabbi to small towns and communities throughout Arkansas and Oklahoma, where he held services and organized Sunday schools. Rabbi Samuel Teitelbaum, who served United Hebrew Congregation from 1927 to 1946 helped found the Arkansas Jewish Assembly and played a key role in the organization’s success. Rabbi Teitelbaum also helped establish a chapter of the Menorah Society at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville (approximately 60 miles to the north), and Fayetteville Jews often attended holiday services in Fort Smith.

Fort Smith’s first Jewish congregation, Temple of Israel, was formed in 1880 under the leadership of President Simon Joel. A second Jewish congregation existed in the early 1880s, and in 1886 the two merged into one congregation, United Hebrew Congregation, with the aid of Rabbi Messing of St. Louis. Neither congregation owned its own building prior to the merger, and the combined congregation met in a retail building and held its first confirmation services at the Christian Church of Fort Smith. As a part of the new congregation, the Temple Ladies’ Aid Society focused on maintaining the choir and aiding the congregation generally. In 1892, United Hebrew Congregation built their own synagogue on the corner of Eleventh and E Streets. The congregation’s second confirmation service was held in the new synagogue, and the congregation owned three Torah scrolls at the time of its dedication.

As United Hebrew Congregation constructed its first permanent home, it also hired its first rabbi, Dr. Abe Traugott, who served the congregation from1892 to 1896. In the thirteen years after Rabbi Traugott’s departure, the congregation doubled in size from 41 to over 80 members. In 1907, Rabbi Edward S. Levy joined United Hebrew Congregation as spiritual leader. He stayed with the congregation until his death in 1914. Rabbi Charles Latz occupied the pulpit after Rabbi Levy’s death and became known for his civic work; he was president of a War Prison Council organized in 1919 and deeply involved in the Fort Smith public library. Additionally, Latz served as a circuit rabbi to small towns and communities throughout Arkansas and Oklahoma, where he held services and organized Sunday schools. Rabbi Samuel Teitelbaum, who served United Hebrew Congregation from 1927 to 1946 helped found the Arkansas Jewish Assembly and played a key role in the organization’s success. Rabbi Teitelbaum also helped establish a chapter of the Menorah Society at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville (approximately 60 miles to the north), and Fayetteville Jews often attended holiday services in Fort Smith.

After the first decade of the 20th century, an increasing number of East European Jews settled in Fort Smith. Some of the newcomers preferred a more traditional worship style, and they organized an Orthodox congregation, B’nai Israel, in 1913. The group met on the second floor of a building on Garrison Avenue. Some of the congregation’s members were very devout in their worship; Ike Pahotski, for instance, took his shoes off at High Holiday services. Up to 30 people attended B’nai Israel for holidays, and the group had two Torah scrolls. The congregation’s membership waned during the 1930s, however, as members either died or moved away, and the group struggled to make a regular minyan (quorum of ten worshippers, traditionally men). A member of the United Hebrew Congregation later recalled that when the Orthodox congregation dissolved in the 1930s several members brought B’nai Israel’s Torah scrolls to the Reform synagogue and asked to become members themselves. One of these former B’nai Israel congregants, Louis Kasten, later served as a lay leader for the temple and, during World War II, assisted US Army Chaplain Rabbi David Seligson with services at nearby Camp Chaffee.

Mid- to Late 20th Century

Union Hebrew Congregation's 1955 synagogue, c. 1990. Photo by Bill Aron.

Union Hebrew Congregation's 1955 synagogue, c. 1990. Photo by Bill Aron.

As of the 1940s, the Fort Smith Jewish community claimed around 250 individuals and more than 50 families—representing a modest net gain since the turn of the century—but membership at United Hebrew Congregation had dropped slightly to 70 households. Nevertheless, the synagogue remained vitally active in Fort Smith.

In 1955 the congregation sold its synagogue to the First Evangelical Lutheran Church in order to build a new facility. During the 1950s the Sunday School had five trained teachers, and the Sisterhood was active, sponsoring square dances, turkey suppers, and canasta tournaments. That same year, a Supper Club was formed that involved discussions led by Rabbi S. Kleinberg.

Fort Smith maintained its status as the second largest city in Arkansas (behind Little Rock) into the 21st century, but the Jewish population declined in the late 20th century. Jewish children often moved away for college and did not return, and the number of Jewish businesses declined, especially in retail. Union Hebrew Congregation employed a fulltime rabbi until 1974, and has relied on student rabbis, visiting clergy, and lay leaders ever since. The congregation held weekly Shabbat services into the 1990s, when it claimed 39 families and enrolled fewer than ten children in religious school.

In 1955 the congregation sold its synagogue to the First Evangelical Lutheran Church in order to build a new facility. During the 1950s the Sunday School had five trained teachers, and the Sisterhood was active, sponsoring square dances, turkey suppers, and canasta tournaments. That same year, a Supper Club was formed that involved discussions led by Rabbi S. Kleinberg.

Fort Smith maintained its status as the second largest city in Arkansas (behind Little Rock) into the 21st century, but the Jewish population declined in the late 20th century. Jewish children often moved away for college and did not return, and the number of Jewish businesses declined, especially in retail. Union Hebrew Congregation employed a fulltime rabbi until 1974, and has relied on student rabbis, visiting clergy, and lay leaders ever since. The congregation held weekly Shabbat services into the 1990s, when it claimed 39 families and enrolled fewer than ten children in religious school.

The 21st Century

Although the city of Fort Smith maintained modest population growth into the early 21st century, Hebrew Union College faced challenges as the Jewish community dwindled. Weekly services continued throughout the 1990s, when Union Hebrew Congregation had thirty-nine families and the Sunday School enrolled three or four children. By the end of the decade, weekly attendance shrank to fewer than ten attendees who met in the temple library.

The congregation became more active in the early 2000s, though, partly due to lay leadership by retired Air Force recruiter Jack Goodman. In 2017 United Hebrew Congregation had about fifty members, conducted regular Shabbat and holiday services under lay leadership, and hired visiting clergy for the High Holidays. The congregation remains small but active as of 2024.

The congregation became more active in the early 2000s, though, partly due to lay leadership by retired Air Force recruiter Jack Goodman. In 2017 United Hebrew Congregation had about fifty members, conducted regular Shabbat and holiday services under lay leadership, and hired visiting clergy for the High Holidays. The congregation remains small but active as of 2024.

Selected Bibliography

Oriel Danielson, “Inside the Jewish Community of Fort Smith, Arkansas,” Forward, 3 January 2017.

Oriel Danielson, “Inside the Jewish Community of Fort Smith, Arkansas,” Forward, 3 January 2017.

Updated March 2024.