Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Columbus, Georgia

|

Columbus: Historical Overview

Located on the eastern bank of the Chattahoochee River, Columbus was created by the Georgia legislature in 1828 as a trading post right across the border of Alabama. Initially, Columbus thrived as a cotton trading town, but soon became an industrial center as a growing number of textile mills and sawmills harnessed the power of the river.

According to some reports, Jews lived in the Columbus area as traders even before the town was officially founded in 1828, laying the groundwork for a Jewish community that endures today. |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Columbus

Raphael Moses

Raphael Moses

Early Settlers

As Columbus’ industrial economy blossomed, growing numbers of Jews were attracted to the west Georgia town. One of these was Jacob I. Moses, who was elected mayor of Columbus in 1844. By 1859, there were 20 Jewish families in Columbus, most of whom were involved in retail trade. Of approximately 37 Jews listed in the 1859 Columbus city directory, 17 were dry goods merchants and 3 were clothing merchants. Another seven were store clerks. Five were skilled craftsmen, including four tinners and one shoemaker. One of these merchants was Rebecca Dessau, who owned her own millinery shop while her husband owned a dry goods business.

This growing number of Jews banded together in 1854, forming the congregation B’nai Israel. Many of these founding members were German immigrants. They initially gathered in members’ homes, but later met in a building on the northeast corner of 10th Street and 5th Avenue. The group also used this rented space for a school, which taught the members’ children about Judaism, as well as Hebrew and German. In 1859, B’nai Israel purchased a house on 10th Street and 4th Avenue, which they converted into a synagogue. The women of the congregation raised the money to furnish the new building and sewed the curtains and ark curtains themselves.

Raphael J. Moses

Perhaps the most notable Jewish citizen of Columbus was Raphael J. Moses. Born and raised in South Carolina, Moses came to Columbus in 1849 from Apalachicola, Florida, where he had been a lawyer. Columbus was closely tied to Apalachicola through the cotton trade and Moses already had contacts and clients in Columbus when he arrived in 1849. Moses became one of the most prominent lawyers in the state of Georgia, but also joined the ranks of Southern planters with his purchase of the Esquiline Plantation. By 1850, Moses already owned 16 slaves. He soon became a pioneer in the development of the commercial peach growing industry in Georgia. In 1851, he became the first planter to sell peaches outside of the state, shipping his produce to New York. He had found a new way to preserve peaches during shipping, using champagne baskets instead of pulverized charcoal. Moses became a very successful planter, which required more labor. By 1860, Moses owned 47 slaves, and was listed as a “farmer” in the US Census, even though he continued his law practice.

As sectional tensions heightened, Moses became a staunch secessionist and a fiery orator for the Southern cause. At 49 years old, Moses was too old to fight for the Confederacy, but was appointed as the Confederate Commissary for Georgia, in charge of supplying and feeding 54,000 Confederate soldiers. His nephew, Edward Warren Moise, who had trained to be a lawyer with his uncle in Columbus, spent $10,000 organizing a company of 120 soldiers which became part of the Confederate army. Once, when food supplies were low, Moses went back to Georgia to make personal appeals for people to donate food and money. During the war, Moses became close with Confederate General Robert E. Lee, and was with him during the Battle of Gettysburg. Three of Moses’ sons fought for the Southern cause, one was killed in battle. Moses is famous for carrying out the last orders of the Confederacy, when President Jefferson Davis ordered him to keep boxes filled with $40,000 worth of gold and silver bullion and make sure it was used to help defeated returning soldiers. Traveling with armed guards after the South’s surrender, Moses took the gold and silver to Augusta, where he negotiated an agreement with a Union general, who promised to use the money to care for and feed former Confederate soldiers.

After the war, Moses returned to Columbus, where he resumed his law practice. He had suffered a financial blow during the war, having invested much of his money in slaves prior to secession. All but one of his former slaves left Esquiline after their emancipation. His net worth went from $55,000 in 1860 to $35,000 in 1870. Since he had not served in political office before the war, Moses was eligible to run. Moses served in the Georgia legislature during Reconstruction and was a fierce critic of the state’s Republican administration.

Moses was never a member of B’nai Israel, though he did have a strong identity as a Jew. When his daughter got married in 1865, he tried unsuccessfully to get a rabbi from New Orleans to perform the ceremony, which took place under a chuppah. In 1878, he backed one candidate for political office, whose opponent raised Moses’ Jewishness as a disqualifying factor. Moses responded to his critics on August 29, 1878 in the local newspaper; his assertion of Jewish pride was reprinted around the country: “I feel it an honor to be of a race whom persecution can not crush, whom prejudice has in vain endeavored to subdue.” When he ran for congress, Moses explained, “I wanted to go to congress as a Jew and because I…would have liked in a public position to confront and do my part towards breaking down the prejudice.” When Moses died in 1893, he was buried in a family cemetery on the Esquiline Plantation.

As Columbus’ industrial economy blossomed, growing numbers of Jews were attracted to the west Georgia town. One of these was Jacob I. Moses, who was elected mayor of Columbus in 1844. By 1859, there were 20 Jewish families in Columbus, most of whom were involved in retail trade. Of approximately 37 Jews listed in the 1859 Columbus city directory, 17 were dry goods merchants and 3 were clothing merchants. Another seven were store clerks. Five were skilled craftsmen, including four tinners and one shoemaker. One of these merchants was Rebecca Dessau, who owned her own millinery shop while her husband owned a dry goods business.

This growing number of Jews banded together in 1854, forming the congregation B’nai Israel. Many of these founding members were German immigrants. They initially gathered in members’ homes, but later met in a building on the northeast corner of 10th Street and 5th Avenue. The group also used this rented space for a school, which taught the members’ children about Judaism, as well as Hebrew and German. In 1859, B’nai Israel purchased a house on 10th Street and 4th Avenue, which they converted into a synagogue. The women of the congregation raised the money to furnish the new building and sewed the curtains and ark curtains themselves.

Raphael J. Moses

Perhaps the most notable Jewish citizen of Columbus was Raphael J. Moses. Born and raised in South Carolina, Moses came to Columbus in 1849 from Apalachicola, Florida, where he had been a lawyer. Columbus was closely tied to Apalachicola through the cotton trade and Moses already had contacts and clients in Columbus when he arrived in 1849. Moses became one of the most prominent lawyers in the state of Georgia, but also joined the ranks of Southern planters with his purchase of the Esquiline Plantation. By 1850, Moses already owned 16 slaves. He soon became a pioneer in the development of the commercial peach growing industry in Georgia. In 1851, he became the first planter to sell peaches outside of the state, shipping his produce to New York. He had found a new way to preserve peaches during shipping, using champagne baskets instead of pulverized charcoal. Moses became a very successful planter, which required more labor. By 1860, Moses owned 47 slaves, and was listed as a “farmer” in the US Census, even though he continued his law practice.

As sectional tensions heightened, Moses became a staunch secessionist and a fiery orator for the Southern cause. At 49 years old, Moses was too old to fight for the Confederacy, but was appointed as the Confederate Commissary for Georgia, in charge of supplying and feeding 54,000 Confederate soldiers. His nephew, Edward Warren Moise, who had trained to be a lawyer with his uncle in Columbus, spent $10,000 organizing a company of 120 soldiers which became part of the Confederate army. Once, when food supplies were low, Moses went back to Georgia to make personal appeals for people to donate food and money. During the war, Moses became close with Confederate General Robert E. Lee, and was with him during the Battle of Gettysburg. Three of Moses’ sons fought for the Southern cause, one was killed in battle. Moses is famous for carrying out the last orders of the Confederacy, when President Jefferson Davis ordered him to keep boxes filled with $40,000 worth of gold and silver bullion and make sure it was used to help defeated returning soldiers. Traveling with armed guards after the South’s surrender, Moses took the gold and silver to Augusta, where he negotiated an agreement with a Union general, who promised to use the money to care for and feed former Confederate soldiers.

After the war, Moses returned to Columbus, where he resumed his law practice. He had suffered a financial blow during the war, having invested much of his money in slaves prior to secession. All but one of his former slaves left Esquiline after their emancipation. His net worth went from $55,000 in 1860 to $35,000 in 1870. Since he had not served in political office before the war, Moses was eligible to run. Moses served in the Georgia legislature during Reconstruction and was a fierce critic of the state’s Republican administration.

Moses was never a member of B’nai Israel, though he did have a strong identity as a Jew. When his daughter got married in 1865, he tried unsuccessfully to get a rabbi from New Orleans to perform the ceremony, which took place under a chuppah. In 1878, he backed one candidate for political office, whose opponent raised Moses’ Jewishness as a disqualifying factor. Moses responded to his critics on August 29, 1878 in the local newspaper; his assertion of Jewish pride was reprinted around the country: “I feel it an honor to be of a race whom persecution can not crush, whom prejudice has in vain endeavored to subdue.” When he ran for congress, Moses explained, “I wanted to go to congress as a Jew and because I…would have liked in a public position to confront and do my part towards breaking down the prejudice.” When Moses died in 1893, he was buried in a family cemetery on the Esquiline Plantation.

The Civil War

Columbus Jews played important roles on the Southern homefront during the Civil War. Louis and Herman Haiman were brothers from Prussia who owned a tinsmith shop and a small sword making business before the war. The demand for their swords peaked after hostilities began, and Louis bought the Muscogee Iron Works during the war. He sent his brother Elias to Europe to ensure that a ready supply of British steel got through the Northern blockade. By 1863, Haiman had 400 workers, many of whom were young boys, turning out 250 swords a day, which made them the largest sword manufacturer in the Confederacy. By the end of the war, Haiman’s factory was also making pistols, though it was soon destroyed by Northern troops. After the war, Haiman literally turned his swords into plowshares, manufacturing plows that he sold to area farmers. Two other brothers, Simon and Frank Rothschild, who had previously owned a dry goods store, started a uniform manufacturing business in Columbus, making 5000 army uniforms during the first year of the war.

Other enterprising Columbus Jews found themselves on the wrong side of the law during the war. Simeon Stern co-owned a dry goods store in Columbus with his brother Bernhardt before the war. In 1862, Simeon was arrested along with another man named Rosenberg for passing counterfeit Confederate money in exchange for cotton. Authorities found $18,000 in counterfeit bills at the Sterns’ business. At the time, there was great concern within the South that the Union was secretly using counterfeit money to undermine the economy of the Confederacy. Stern’s arrest led to suspicion being cast on L.G. Sternheimer, a mohel who also led services for the B’nai Israel congregation. A boarder who lived with the Sterns, Sternheimer also passed some counterfeit bills, though he claimed ignorance of their shady provenance. When Sternheimer was interviewing for a job with Macon’s Jewish congregation a few years later, he had to once again defend his innocence from this plot. Since he was never charged, Sternheimer was hired by the Macon congregation.

Rabbinic Leadership

During the Civil War, Columbus’ B’nai Israel sought to hire Rabbi James Gutheim, who had left his congregation in New Orleans after refusing to take a loyalty oath to the Union. Rabbi Gutheim, who had become a folk hero to Southern Jews loyal to the Confederacy, accepted a pulpit in Montgomery instead. The members of B’nai Israel were able to convince the Montgomery congregation to share Rabbi Gutheim, who traveled to Columbus once every six weeks to lead Shabbat services. A few years later, Rabbi Gutheim left for a pulpit in New York City.

For the next few decades, B’nai Israel rarely had rabbinic leadership. The congregation was still orthodox in its worship practices and its members still observed Rosh Hashanah for the traditional two days in 1866. Eventually, B’nai Israel embraced Reform Judaism, becoming a member of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations in 1875. The congregation cut back observance of Jewish holidays to one day, and incorporated more English into the service. The congregation of 36 members was desperate to hire someone who could speak German and English, lead services, and teach Hebrew to the congregation’s children. In 1886, they hired Rabbi Louis Weiss, who stayed in Columbus only two years. By 1891, they had a co-ed choir and an organ.

In 1893, B'nai Israel hired Rabbi Edward Benjamin Morris Browne, who stayed until 1901. He received his medical degree and his rabbinic ordination from Cincinnati College in 1869. In 1895, the Rabbi was invited to represent the Jewish community at the funeral of President Ulysses S. Grant. In accepting the honor, he announced that he would not require a horse or carriage for the procession, since the ceremony took place on a Saturday. In his strict observance of the day, the Rabbi walked the entire length of the funeral processional which stretched close to the entire length of Manhattan from Battery Place to 123rd street. He made a pilgrimage to Grant’s burial site every year up until 1913. His wife Sophia served as a member of the League of Women Voters. In 1922, she attended the League-sponsored Pan American Conference in 1922, the first international conference dedicated to the improvement of women’s issues around the world.

Columbus Jews played important roles on the Southern homefront during the Civil War. Louis and Herman Haiman were brothers from Prussia who owned a tinsmith shop and a small sword making business before the war. The demand for their swords peaked after hostilities began, and Louis bought the Muscogee Iron Works during the war. He sent his brother Elias to Europe to ensure that a ready supply of British steel got through the Northern blockade. By 1863, Haiman had 400 workers, many of whom were young boys, turning out 250 swords a day, which made them the largest sword manufacturer in the Confederacy. By the end of the war, Haiman’s factory was also making pistols, though it was soon destroyed by Northern troops. After the war, Haiman literally turned his swords into plowshares, manufacturing plows that he sold to area farmers. Two other brothers, Simon and Frank Rothschild, who had previously owned a dry goods store, started a uniform manufacturing business in Columbus, making 5000 army uniforms during the first year of the war.

Other enterprising Columbus Jews found themselves on the wrong side of the law during the war. Simeon Stern co-owned a dry goods store in Columbus with his brother Bernhardt before the war. In 1862, Simeon was arrested along with another man named Rosenberg for passing counterfeit Confederate money in exchange for cotton. Authorities found $18,000 in counterfeit bills at the Sterns’ business. At the time, there was great concern within the South that the Union was secretly using counterfeit money to undermine the economy of the Confederacy. Stern’s arrest led to suspicion being cast on L.G. Sternheimer, a mohel who also led services for the B’nai Israel congregation. A boarder who lived with the Sterns, Sternheimer also passed some counterfeit bills, though he claimed ignorance of their shady provenance. When Sternheimer was interviewing for a job with Macon’s Jewish congregation a few years later, he had to once again defend his innocence from this plot. Since he was never charged, Sternheimer was hired by the Macon congregation.

Rabbinic Leadership

During the Civil War, Columbus’ B’nai Israel sought to hire Rabbi James Gutheim, who had left his congregation in New Orleans after refusing to take a loyalty oath to the Union. Rabbi Gutheim, who had become a folk hero to Southern Jews loyal to the Confederacy, accepted a pulpit in Montgomery instead. The members of B’nai Israel were able to convince the Montgomery congregation to share Rabbi Gutheim, who traveled to Columbus once every six weeks to lead Shabbat services. A few years later, Rabbi Gutheim left for a pulpit in New York City.

For the next few decades, B’nai Israel rarely had rabbinic leadership. The congregation was still orthodox in its worship practices and its members still observed Rosh Hashanah for the traditional two days in 1866. Eventually, B’nai Israel embraced Reform Judaism, becoming a member of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations in 1875. The congregation cut back observance of Jewish holidays to one day, and incorporated more English into the service. The congregation of 36 members was desperate to hire someone who could speak German and English, lead services, and teach Hebrew to the congregation’s children. In 1886, they hired Rabbi Louis Weiss, who stayed in Columbus only two years. By 1891, they had a co-ed choir and an organ.

In 1893, B'nai Israel hired Rabbi Edward Benjamin Morris Browne, who stayed until 1901. He received his medical degree and his rabbinic ordination from Cincinnati College in 1869. In 1895, the Rabbi was invited to represent the Jewish community at the funeral of President Ulysses S. Grant. In accepting the honor, he announced that he would not require a horse or carriage for the procession, since the ceremony took place on a Saturday. In his strict observance of the day, the Rabbi walked the entire length of the funeral processional which stretched close to the entire length of Manhattan from Battery Place to 123rd street. He made a pilgrimage to Grant’s burial site every year up until 1913. His wife Sophia served as a member of the League of Women Voters. In 1922, she attended the League-sponsored Pan American Conference in 1922, the first international conference dedicated to the improvement of women’s issues around the world.

Temple B'nai Israel

Temple B'nai Israel

Organized Jewish Life in Columbus

In addition to B’nai Israel, Columbus Jews began to found other Jewish organizations in the years after the Civil War. In 1866, they established a local chapter of the Jewish fraternal society B’nai B’rith. In 1870, Columbus Jews founded a Jewish social organization called Columbus Concordia. Later known as the Harmony Club, the organization was create to alleviate the “monotonous evenings and Sundays in this city,” according to its minutes. The group soon rented a room and purchased twelve decks of playing cards, two sets of dominoes, one checker board, and five boxes of cigars. A purely social organization, the Harmony Club remained active for over a century. In 1874, Jewish women in Columbus founded the Daughters of Israel to provide charity and assistance to those in need. Rebecca Dessau led the organization for 15 years. The group later changed its name to the Jewish Ladies Aid Society.

In 1885, the Daughters of Israel passed a resolution calling on B’nai Israel to build a proper synagogue for the congregation, which had outgrown the house they had been using as a meeting place. Finally, in November of 1886, they broke ground on a new synagogue after moving the house to the lot next door. When the Byzantine-style synagogue was dedicated in September of 1887, the local newspaper called it “one of the most beautiful buildings in the city. It would be an ornament to a city thrice the size of Columbus.” The dedication drew a large crowd, with many non-Jews and Christian ministers in the audience. Rabbi S. Hecht from Montgomery gave the keynote address during the three-hour dedication service. Later that night, the congregation held a banquet at which Columbus’ mayor C.B Grimes was an honored guest. B’nai Israel’s president, Leopold Lowenherz, thanked the non-Jews of Columbus for helping in the effort to build the synagogue, calling it a “monument” to their “liberal sentiment, culture, generosity, and good feeling.” The editor of the Columbus Daily Enquirer had a great time at the banquet, commenting, “at a Jewish banquet they certainly know how to ‘set up’ the wine. Did you ever attend a Jewish celebration that you did not have the best time you ever had?”

The Jews who celebrated the dedication of B’nai Israel’s new temple were quite different from the ones who had formed the congregation 33 years earlier. Of the 20 Jewish families who had organized B’nai Israel, virtually none remained in Columbus in the years after the Civil War. These early Jewish settlers had been replaced by a new wave of German Jewish immigrants, such as Emmanuel Kern, who came to Columbus from Bavaria in 1867. Kern was soon followed by his brother-in-law Solomon Loeb as the two became partners in a dry goods store. Later, they opened a wholesale grocery business. After Kern died, it became known as the Sol Loeb Wholesale Grocery Company, which remained in business, run by Sol’s descendants, until recently. In the late 19th century, Columbus Jews continued to be concentrated in retail trade. According to the local newspaper, in 1891, more than 50 Jewish-owned stores closed on Yom Kippur. In 1907, the newspaper reported that it “looked odd to see so many stores closed on Monday” and that the number of closed businesses on the Jewish holiday reflected “how prominently the Jews are identified with the city’s business life.”

Despite this growth in Columbus’ Jewish population, B’nai Israel soon found itself in financial trouble along with much of the rest of the country in the 1890s. They were having a hard time paying the mortgage on their new synagogue. In response, the Jewish Ladies Aid Society wrote to the widow of the great French Jewish philanthropist Baron DeHirsch to ask for financial help. The Baroness DeHirsch responded to this plea, sending almost $2000 to the congregation, which was enough to pay off the remaining debt on the synagogue. The congregation installed a memorial window in honor of the Baron and his wife and began to read the DeHirsch’s names during the Yizkor service on Yom Kippur, a practice they continue to this day.

The Ladies Aid Society

The Ladies Aid Society of B’nai Israel had other creative methods of raising money for the congregation. In 1886, as B’nai Israel was working to raise the funds for a new synagogue, the Ladies Aid Society held a week-long Jewish Fair, at which they sold food and various merchandise. Held in an empty store the week before Christmas, the fair offered “a nice line of Christmas goods, quilts, curtains, lace goods and many other articles” including cigars and donated goods. Fair goers could also have a session with a fortune teller, played by a member of the Ladies Aid Society. The local newspaper covered the fair in detail and urged its readers to support it, writing that Columbus Jews are “ever ready to extend a helping hand to others. Now…once in a lifetime, they ask the public to help them build a new synagogue, and we hope the citizens will respond liberally.” The 1886 Jewish Fair was very successful and the Ladies Aid Society was able to make a substantial donation to B’nai Israel’s building fund.

Over the years, as the need arose, the Ladies Aid Society would hold additional fairs. In 1903, the fair helped to raise money to refurbish the temple’s vestry rooms. The temple suffered a fire in 1907, which destroyed much of its interior. In 1908, the Ladies Aid Society held an elaborate bazaar that sold furniture, dry goods, jewelry, cut glass, and candy, in addition to running a restaurant and Japanese tea garden in the store. Columbus’ mayor formally opened the bazaar that year. The restaurant was open from 10 am to 11 pm each day and specialized in oysters, “which are served in as many varieties as a gentleman has quarter dollars.” The Ladies Aid Society Bazaar looked a lot like the department stores members’ husbands owned, though most of their merchandise was donated and their enterprise was only open for a week. These temporary stores were a lot of work for the women, but they could be quite successful. In 1908, the Ladies Aid Society raised over $1500 from the bazaar. Other bazaars were held in 1910 and 1916.

In addition to B’nai Israel, Columbus Jews began to found other Jewish organizations in the years after the Civil War. In 1866, they established a local chapter of the Jewish fraternal society B’nai B’rith. In 1870, Columbus Jews founded a Jewish social organization called Columbus Concordia. Later known as the Harmony Club, the organization was create to alleviate the “monotonous evenings and Sundays in this city,” according to its minutes. The group soon rented a room and purchased twelve decks of playing cards, two sets of dominoes, one checker board, and five boxes of cigars. A purely social organization, the Harmony Club remained active for over a century. In 1874, Jewish women in Columbus founded the Daughters of Israel to provide charity and assistance to those in need. Rebecca Dessau led the organization for 15 years. The group later changed its name to the Jewish Ladies Aid Society.

In 1885, the Daughters of Israel passed a resolution calling on B’nai Israel to build a proper synagogue for the congregation, which had outgrown the house they had been using as a meeting place. Finally, in November of 1886, they broke ground on a new synagogue after moving the house to the lot next door. When the Byzantine-style synagogue was dedicated in September of 1887, the local newspaper called it “one of the most beautiful buildings in the city. It would be an ornament to a city thrice the size of Columbus.” The dedication drew a large crowd, with many non-Jews and Christian ministers in the audience. Rabbi S. Hecht from Montgomery gave the keynote address during the three-hour dedication service. Later that night, the congregation held a banquet at which Columbus’ mayor C.B Grimes was an honored guest. B’nai Israel’s president, Leopold Lowenherz, thanked the non-Jews of Columbus for helping in the effort to build the synagogue, calling it a “monument” to their “liberal sentiment, culture, generosity, and good feeling.” The editor of the Columbus Daily Enquirer had a great time at the banquet, commenting, “at a Jewish banquet they certainly know how to ‘set up’ the wine. Did you ever attend a Jewish celebration that you did not have the best time you ever had?”

The Jews who celebrated the dedication of B’nai Israel’s new temple were quite different from the ones who had formed the congregation 33 years earlier. Of the 20 Jewish families who had organized B’nai Israel, virtually none remained in Columbus in the years after the Civil War. These early Jewish settlers had been replaced by a new wave of German Jewish immigrants, such as Emmanuel Kern, who came to Columbus from Bavaria in 1867. Kern was soon followed by his brother-in-law Solomon Loeb as the two became partners in a dry goods store. Later, they opened a wholesale grocery business. After Kern died, it became known as the Sol Loeb Wholesale Grocery Company, which remained in business, run by Sol’s descendants, until recently. In the late 19th century, Columbus Jews continued to be concentrated in retail trade. According to the local newspaper, in 1891, more than 50 Jewish-owned stores closed on Yom Kippur. In 1907, the newspaper reported that it “looked odd to see so many stores closed on Monday” and that the number of closed businesses on the Jewish holiday reflected “how prominently the Jews are identified with the city’s business life.”

Despite this growth in Columbus’ Jewish population, B’nai Israel soon found itself in financial trouble along with much of the rest of the country in the 1890s. They were having a hard time paying the mortgage on their new synagogue. In response, the Jewish Ladies Aid Society wrote to the widow of the great French Jewish philanthropist Baron DeHirsch to ask for financial help. The Baroness DeHirsch responded to this plea, sending almost $2000 to the congregation, which was enough to pay off the remaining debt on the synagogue. The congregation installed a memorial window in honor of the Baron and his wife and began to read the DeHirsch’s names during the Yizkor service on Yom Kippur, a practice they continue to this day.

The Ladies Aid Society

The Ladies Aid Society of B’nai Israel had other creative methods of raising money for the congregation. In 1886, as B’nai Israel was working to raise the funds for a new synagogue, the Ladies Aid Society held a week-long Jewish Fair, at which they sold food and various merchandise. Held in an empty store the week before Christmas, the fair offered “a nice line of Christmas goods, quilts, curtains, lace goods and many other articles” including cigars and donated goods. Fair goers could also have a session with a fortune teller, played by a member of the Ladies Aid Society. The local newspaper covered the fair in detail and urged its readers to support it, writing that Columbus Jews are “ever ready to extend a helping hand to others. Now…once in a lifetime, they ask the public to help them build a new synagogue, and we hope the citizens will respond liberally.” The 1886 Jewish Fair was very successful and the Ladies Aid Society was able to make a substantial donation to B’nai Israel’s building fund.

Over the years, as the need arose, the Ladies Aid Society would hold additional fairs. In 1903, the fair helped to raise money to refurbish the temple’s vestry rooms. The temple suffered a fire in 1907, which destroyed much of its interior. In 1908, the Ladies Aid Society held an elaborate bazaar that sold furniture, dry goods, jewelry, cut glass, and candy, in addition to running a restaurant and Japanese tea garden in the store. Columbus’ mayor formally opened the bazaar that year. The restaurant was open from 10 am to 11 pm each day and specialized in oysters, “which are served in as many varieties as a gentleman has quarter dollars.” The Ladies Aid Society Bazaar looked a lot like the department stores members’ husbands owned, though most of their merchandise was donated and their enterprise was only open for a week. These temporary stores were a lot of work for the women, but they could be quite successful. In 1908, the Ladies Aid Society raised over $1500 from the bazaar. Other bazaars were held in 1910 and 1916.

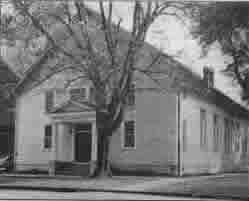

Chevra Sharis Israel's first synagogue

Chevra Sharis Israel's first synagogue

A Diverse Community

By the 1890s, increasing numbers of Jews from Eastern Europe began to settle in Columbus. These Jewish immigrants did not feel comfortable in the Reform temple of B’nai Israel and, in 1892, 15 of them organized their own Orthodox congregation, Chevra Sharis Israel. They first met on the second floor of a downtown building and later in the local Odd Fellows Hall. The small congregation did not have a rabbi in its early years. In 1915, a group of members each paid $100 to buy land at the corner of 1st Avenue and 7th Street for a permanent synagogue for the congregation. Of the 11 men who pitched in to buy the land, ten were Russian-born immigrants. Nine had come to the United States after 1897. The 40 members of Chevra Sharis Israel dedicated their congregation’s first synagogue in September of 1915. With a stucco exterior, the building could seat 500 people, including a balcony designed for the women of the congregation. They were able to get an ark from the small Jewish community of Eufaula, Alabama, who did not have a synagogue. Most members of the congregation lived in the area around the new synagogue.

Soon after dedicating the synagogue, Chevra Sharis Israel hired it first rabbi, Joseph Werbin, who had immigrated to the United States from Russia in 1906. Rabbi Werbin also served as a shochet (kosher butcher) and mohel (ritual circumciser) for the congregation, until he left in 1922. Sharis Israel had a great deal of rabbinic turnover during this period, with four different rabbis leading the congregation during the eight years after Werbin left. Despite this leadership instability, the congregation grew quickly after it dedicated its building, with its membership doubling. In 1919, they had 50 students in their religious school, which met every day after school. In 1909, 17 female members of Sharis Israel founded the Jewish Ladies Relief Society, which later became the congregation’s Sisterhood. This organization raised money to support the synagogue and Jewish charities.

By the 1890s, increasing numbers of Jews from Eastern Europe began to settle in Columbus. These Jewish immigrants did not feel comfortable in the Reform temple of B’nai Israel and, in 1892, 15 of them organized their own Orthodox congregation, Chevra Sharis Israel. They first met on the second floor of a downtown building and later in the local Odd Fellows Hall. The small congregation did not have a rabbi in its early years. In 1915, a group of members each paid $100 to buy land at the corner of 1st Avenue and 7th Street for a permanent synagogue for the congregation. Of the 11 men who pitched in to buy the land, ten were Russian-born immigrants. Nine had come to the United States after 1897. The 40 members of Chevra Sharis Israel dedicated their congregation’s first synagogue in September of 1915. With a stucco exterior, the building could seat 500 people, including a balcony designed for the women of the congregation. They were able to get an ark from the small Jewish community of Eufaula, Alabama, who did not have a synagogue. Most members of the congregation lived in the area around the new synagogue.

Soon after dedicating the synagogue, Chevra Sharis Israel hired it first rabbi, Joseph Werbin, who had immigrated to the United States from Russia in 1906. Rabbi Werbin also served as a shochet (kosher butcher) and mohel (ritual circumciser) for the congregation, until he left in 1922. Sharis Israel had a great deal of rabbinic turnover during this period, with four different rabbis leading the congregation during the eight years after Werbin left. Despite this leadership instability, the congregation grew quickly after it dedicated its building, with its membership doubling. In 1919, they had 50 students in their religious school, which met every day after school. In 1909, 17 female members of Sharis Israel founded the Jewish Ladies Relief Society, which later became the congregation’s Sisterhood. This organization raised money to support the synagogue and Jewish charities.

Rabbi Frank Rosenthal

Rabbi Frank Rosenthal

If Sharis Israel became the home of Columbus’s Russian Jewish immigrants, B’nai Israel remained the center of the city’s native-born and German Jews. Of eleven members of the 1904 confirmation class, nine were born in Georgia. Of their parents, 36% were native born, while 55% were born in Germany. Most of these immigrant parents had been in the United States for a long time by 1904. The congregation grew as well, from 48 members in 1905 to 85 in 1925. A big reason for this growth was Rabbi Frank Rosenthal who came to Columbus from Baton Rouge in 1907. Rosenthal led the effort to rebuild the synagogue after it was damaged by a fire at the end of 1907. He became very involved with local civic organizations, becoming a charter member of the Kiwanis Club and an active member of the Masons and the Woodmen of the World. Rabbi Rosenthal was also a leader of the local B’nai B’rith and helped to push for the construction of the B’nai B’rith Hospital in Hot Springs, Arkansas. Rosenthal served as the spiritual leader of B’nai Israel for 33 years.

The Early 20th Century

The Jewish population of Columbus grew from 300 Jews in the late 19th century to 735 in 1937. Most concentrated in retail trade, but a handful got involved with Columbus’ bustling industrial economy. For instance in 1886, David and Gerson Rothschild opened a dry goods business which is still in existence today as a manufacturer of upholstery fabric. In 1919, Jewish-owned stores dotted downtown Columbus, including the Emporium, Ed Cohn’s Store, Loewenherz Brothers, and the Leader. Abe Straus started with the John Archer Mitchell Hosiery Mill as secretary/treasurer in 1920. By 1923, Straus had become the president of one of the largest manufacturing concerns in Columbus. Five years later, he bought the company and built a big new factory on Talbotton Road. Simon Schwob, a Jewish tailor from Alsace, moved to Columbus in 1912, opening a clothing store in downtown called the Standard Tailoring Company. Schwob soon started to make the suits that he sold in his store. From this modest start, Schwob built a large clothing manufacturing business in Columbus. When Simon died in 1954, his widow Ruth took over the company. In 1976, the family sold the business. While no Schwobs remain in Columbus today, the legacy of the family’s philanthropy lives on with the Schwob Library and Schwob School of Music at Columbus State University.

The Early 20th Century

The Jewish population of Columbus grew from 300 Jews in the late 19th century to 735 in 1937. Most concentrated in retail trade, but a handful got involved with Columbus’ bustling industrial economy. For instance in 1886, David and Gerson Rothschild opened a dry goods business which is still in existence today as a manufacturer of upholstery fabric. In 1919, Jewish-owned stores dotted downtown Columbus, including the Emporium, Ed Cohn’s Store, Loewenherz Brothers, and the Leader. Abe Straus started with the John Archer Mitchell Hosiery Mill as secretary/treasurer in 1920. By 1923, Straus had become the president of one of the largest manufacturing concerns in Columbus. Five years later, he bought the company and built a big new factory on Talbotton Road. Simon Schwob, a Jewish tailor from Alsace, moved to Columbus in 1912, opening a clothing store in downtown called the Standard Tailoring Company. Schwob soon started to make the suits that he sold in his store. From this modest start, Schwob built a large clothing manufacturing business in Columbus. When Simon died in 1954, his widow Ruth took over the company. In 1976, the family sold the business. While no Schwobs remain in Columbus today, the legacy of the family’s philanthropy lives on with the Schwob Library and Schwob School of Music at Columbus State University.

Jewish stores lined the streets of downtown Columbus

Jewish stores lined the streets of downtown Columbus

The World Wars

Manufacturing businesses thrived during wartime as the world wars helped to transform the city of Columbus. In 1918, the US War Department created Camp Benning just outside of Columbus to provide basic training for new soldiers. Made permanent in 1922, Fort Benning eventually grew into one of the largest military bases in the country. Rabbi Rosenthal led services for soldiers at Fort Benning and served as president of the Jewish Welfare Board during the Great War. Many Columbus Jews hosted Jewish soldiers in their homes during the war. Local Jews would provide various entertainment programs for the soldiers, including parties at the Harmony Club. When large numbers of Jewish soldiers were stationed at Fort Benning in World War II, Columbus Jews responded with hospitality once again. The local Junior Hadassah Chapter hosted Friday night receptions each week at Fort Benning, while the Harmony Club hosted mid-week dances for the soldiers.

Columbus Jews also took part in national fundraising campaigns to help suffering Jews in Europe during World War I. In 1918, Rabbi Rosenthal, Leopold Loewenherz, and Morris Loeb headed the local Jewish War Relief Fund campaign, which aimed to raise $20,000 in Columbus. Seeking to solicit contributions from the Gentile community, they asked prominent local businessman J. Homer Dimon to be chairman of the committee. Several other non-Jews, including Christian ministers, served on neighborhood committees for the relief drive. In a letter published in the local newspaper, the committee stated that while Columbus Jews would take the lead, “we request every citizen of the county to assist in this crying need.” The local newspaper editor endorsed the 1920 Jewish War Relief Campaign, which was kicked off at a mass meeting held at the First Baptist Church, by writing that since Columbus Jews had always given to local causes, that non-Jews in Columbus should support this worthwhile cause. Local Gentiles donated over $1000 to the Jewish War Relief Fund in 1920.

Zionism in Columbus

Some Columbus Jews saw a Jewish homeland as the solution to the plight of Europe’s Jews. Noted Zionist Bella Pevsner came to Columbus in 1918, speaking to a capacity crowd at Temple B’nai Israel. Leopold Loewenherz, the former president of the Reform congregation, introduced Pevsner. The following year, another Zionist organizer, Samuel Blitz, came to Columbus and spoke at a mass meeting at a local auditorium. According to the Columbus Daily Enquirer, “a large number of Jews and Gentiles were present and listened with deep interest to the speaker.” In an effort to signal that Zionism was not incompatible with American patriotism, the meeting opened with the singing of the “Star-Spangled Banner.” During his speech, Blitz lived up to his name, excoriating Jewish opponents of Zionism as “traitors to the Jewish people.” The day after Blitz’s speech, Columbus Jews founded a local Zionist district affiliated with the Zionist Organization of America.

In many other Southern cities, Reform Jews tended to oppose Zionism, but in Columbus, B’nai Israel’s Rabbi Rosenthal gave the invocation before Blitz’s speech. Still, most members of the new Zionist organization were immigrants from Russia and Poland and members of Sharis Israel. In 1945, Sharis Israel held a special service in honor of the 28th anniversary of the Balfour Declaration, which was Great Britain’s expression of support for a Jewish homeland in Palestine. That same year, Columbus women formed a chapter of Hadassah, with the wife of Sharis Israel’s Rabbi Aaron Funk serving as president. Though it was started relatively late, Columbus’ Hadassah chapter eventually became the largest Jewish women’s organization in the city, attracting members from both congregations. It raised money for the Hadassah Hospital in Israel as well as local causes. They would hold annual musical theater productions as fundraisers. The Columbus Hadassah chapter later funded the library at the local Ronald McDonald House.

Manufacturing businesses thrived during wartime as the world wars helped to transform the city of Columbus. In 1918, the US War Department created Camp Benning just outside of Columbus to provide basic training for new soldiers. Made permanent in 1922, Fort Benning eventually grew into one of the largest military bases in the country. Rabbi Rosenthal led services for soldiers at Fort Benning and served as president of the Jewish Welfare Board during the Great War. Many Columbus Jews hosted Jewish soldiers in their homes during the war. Local Jews would provide various entertainment programs for the soldiers, including parties at the Harmony Club. When large numbers of Jewish soldiers were stationed at Fort Benning in World War II, Columbus Jews responded with hospitality once again. The local Junior Hadassah Chapter hosted Friday night receptions each week at Fort Benning, while the Harmony Club hosted mid-week dances for the soldiers.

Columbus Jews also took part in national fundraising campaigns to help suffering Jews in Europe during World War I. In 1918, Rabbi Rosenthal, Leopold Loewenherz, and Morris Loeb headed the local Jewish War Relief Fund campaign, which aimed to raise $20,000 in Columbus. Seeking to solicit contributions from the Gentile community, they asked prominent local businessman J. Homer Dimon to be chairman of the committee. Several other non-Jews, including Christian ministers, served on neighborhood committees for the relief drive. In a letter published in the local newspaper, the committee stated that while Columbus Jews would take the lead, “we request every citizen of the county to assist in this crying need.” The local newspaper editor endorsed the 1920 Jewish War Relief Campaign, which was kicked off at a mass meeting held at the First Baptist Church, by writing that since Columbus Jews had always given to local causes, that non-Jews in Columbus should support this worthwhile cause. Local Gentiles donated over $1000 to the Jewish War Relief Fund in 1920.

Zionism in Columbus

Some Columbus Jews saw a Jewish homeland as the solution to the plight of Europe’s Jews. Noted Zionist Bella Pevsner came to Columbus in 1918, speaking to a capacity crowd at Temple B’nai Israel. Leopold Loewenherz, the former president of the Reform congregation, introduced Pevsner. The following year, another Zionist organizer, Samuel Blitz, came to Columbus and spoke at a mass meeting at a local auditorium. According to the Columbus Daily Enquirer, “a large number of Jews and Gentiles were present and listened with deep interest to the speaker.” In an effort to signal that Zionism was not incompatible with American patriotism, the meeting opened with the singing of the “Star-Spangled Banner.” During his speech, Blitz lived up to his name, excoriating Jewish opponents of Zionism as “traitors to the Jewish people.” The day after Blitz’s speech, Columbus Jews founded a local Zionist district affiliated with the Zionist Organization of America.

In many other Southern cities, Reform Jews tended to oppose Zionism, but in Columbus, B’nai Israel’s Rabbi Rosenthal gave the invocation before Blitz’s speech. Still, most members of the new Zionist organization were immigrants from Russia and Poland and members of Sharis Israel. In 1945, Sharis Israel held a special service in honor of the 28th anniversary of the Balfour Declaration, which was Great Britain’s expression of support for a Jewish homeland in Palestine. That same year, Columbus women formed a chapter of Hadassah, with the wife of Sharis Israel’s Rabbi Aaron Funk serving as president. Though it was started relatively late, Columbus’ Hadassah chapter eventually became the largest Jewish women’s organization in the city, attracting members from both congregations. It raised money for the Hadassah Hospital in Israel as well as local causes. They would hold annual musical theater productions as fundraisers. The Columbus Hadassah chapter later funded the library at the local Ronald McDonald House.

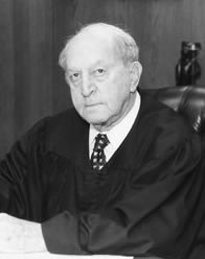

Judge Aaron Cohn

Judge Aaron Cohn

Civic Engagement

Hadassah’s local charitable activity is part of a long tradition of Jews being active in civic life in Columbus. In the 1880s, Issac Isaiah Moses was a major advocate for Columbus’ public school system, serving as superintendent and securing funding from the Peabody Foundation for local schools. When he died, the local newspaper wrote that Moses had done “more than any single individual in this section” for public education. In 1925, Laura Rosenberg created the Milk Fund, which gave free milk to needy students at nine different schools in Columbus. Rosenberg remained the head of the fund until her death in 1950. Rosenberg was involved in several other local causes related to children. In 1931, she was named the outstanding citizen in Columbus by the Lion’s Club. Sidney Goldberg Simons served on the Metro Planning Commission, the board of the local medical center, and on many other local boards. When he died in 1968, the city named Simons Plaza after him. Maurice Rothschild served on the local school board in 1949; the city honored his service by naming a junior high school after him.

No Columbus Jew was more involved with children’s issues than Aaron Cohn, who served as a juvenile justice judge for 46 years. Cohn served as an officer under General Patton during World War II, helping to liberate the Ebensee Concentration Camp. First appointed in 1964, Cohn won multiple honors for his service to the community. In 2003, he became the longest sitting juvenile court judge in the country. Cohn was on the bench helping to guide the lives of troubled children until 10 months before his death in 2012, at the age of 96.

Hadassah’s local charitable activity is part of a long tradition of Jews being active in civic life in Columbus. In the 1880s, Issac Isaiah Moses was a major advocate for Columbus’ public school system, serving as superintendent and securing funding from the Peabody Foundation for local schools. When he died, the local newspaper wrote that Moses had done “more than any single individual in this section” for public education. In 1925, Laura Rosenberg created the Milk Fund, which gave free milk to needy students at nine different schools in Columbus. Rosenberg remained the head of the fund until her death in 1950. Rosenberg was involved in several other local causes related to children. In 1931, she was named the outstanding citizen in Columbus by the Lion’s Club. Sidney Goldberg Simons served on the Metro Planning Commission, the board of the local medical center, and on many other local boards. When he died in 1968, the city named Simons Plaza after him. Maurice Rothschild served on the local school board in 1949; the city honored his service by naming a junior high school after him.

No Columbus Jew was more involved with children’s issues than Aaron Cohn, who served as a juvenile justice judge for 46 years. Cohn served as an officer under General Patton during World War II, helping to liberate the Ebensee Concentration Camp. First appointed in 1964, Cohn won multiple honors for his service to the community. In 2003, he became the longest sitting juvenile court judge in the country. Cohn was on the bench helping to guide the lives of troubled children until 10 months before his death in 2012, at the age of 96.

Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler

Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler

The Community Thrives

Both of Columbus’ congregations thrived in the years after World War II. By the 1940s, Sharis Israel, soon to be renamed Shearith Israel Synagogue, had 100 members and a full-time rabbi and shochet. After the congregation’s post-war growth spurt, they had outgrown their building. The religious school couldn’t fit into the available classrooms, and classes started to meet in different corners of the sanctuary. Finally, under the leadership of board chairman Sol Singer, Shearith Israel, now numbering 124 member households, raised money for a new $150,000 building on Wynnton Road. The new sanctuary could seat 300 people; the synagogue also included a smaller chapel, a social room, a kitchen, and six classrooms. When Shearith Israel dedicated their new synagogue in February of 1951, Columbus Mayor B.F. Register cut the ribbon and Rabbi Alfred Goodman of B’nai Israel gave the opening prayer. Rabbi Jacob Agus of Baltimore gave the keynote address in a ceremony that included the singing of both “America” and “Hatikvah,” the Israeli national anthem.

As Shearith Israel moved into their new building, they also moved away from Orthodox Judaism. Through the 1940s, Shearith Israel was still Orthodox, with separate seating for men and women in the sanctuary and a mikvah (Jewish ritual bath). Many members still walked to shul. In 1949, the congregation celebrated its first bat mitzvah ceremony, in which a 13-year-old girl celebrated the coming of age ritual traditionally performed by boys. In 1950, their new rabbi, Emanuel Bennet, instituted mixed-gender seating and introduced some English into the Shabbat service. In 1952, under the leadership of newly hired Rabbi Kassel Abelson, Shearith Israel officially joined the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism. That same year, the congregation celebrated its first confirmation ceremony. Although Shearith Israel had officially become Conservative, the congregation still maintained some traditional practices, including daily minyans and a strictly kosher kitchen. Each male member was assigned monthly minyan duty, in which he would be responsible for getting ten men to attend that day’s prayer meeting. In 1974, under the leadership of Rabbi Theodore Feldman, Shearith Israel granted full equality to female members, allowing them to receive Torah honors and count towards the minyan. In the 1980s, Shearith Israel reached a peak of 150 families and continued to hold daily minyans. The congregation also had a kosher meat co-op, in which 30 members banded together to order kosher meat from Chicago and Atlanta several times a year.

B’nai Israel, now known as Temple Israel, also thrived in the years after World War II. In 1940, 80 families belonged to the Reform congregation; this figure grew to 119 in 1962 and peaked at 182 in 1982. Like Shearith Israel, Temple Israel outgrew its building. Just as they had done in 1885, the women of the congregation led the way: in 1952, the Jewish Ladies Aid Society passed a resolution labeling their current temple inadequate and calling for the construction of a new synagogue. Finally, in 1957, Temple Israel broke ground on a new synagogue on Wildwood Avenue. When they dedicated the building the following year, they led a procession with the Torahs from the old temple to the new one. Rabbi William Silverman from Nashville’s Ohabai Sholom congregation was the keynote speaker during the dedication which drew 350 people. This move to their new home took place during the long tenure of Rabbi Alfred Goodman, who led Temple Israel from 1950 to 1983.

While the Columbus Jewish community remained divided into two congregations, they united to help Jews in need. In 1939, Columbus Jews worked to bring in Jewish refugees from Germany. Victor Kiralfy was chairman of a coordinating committee that tried to bring a refugee family to Columbus every month, until the war made it impossible. Simon and Ruth Schwob also played a leading role in these efforts. Simon Schwob led the way in organizing the Columbus Jewish Welfare Federation in 1944. Their organizing meeting was held in Schwob’s office, and the clothing manufacturer served as the federation’s first president. During Israel’s 1967 War, the federation conducted an emergency fund drive which raised $110,000 for the Jewish state. When Israel was attacked on Yom Kippur in 1973, the Columbus Jewish Welfare Federation raised $170,000 for the Israeli war effort. In the 1960s, Shearith Israel started a nursery school for the children of the congregation. Later, the school became a Jewish community nursery school under the auspices of the Jewish Welfare Federation. The school closed in 1989.

Both of Columbus’ congregations thrived in the years after World War II. By the 1940s, Sharis Israel, soon to be renamed Shearith Israel Synagogue, had 100 members and a full-time rabbi and shochet. After the congregation’s post-war growth spurt, they had outgrown their building. The religious school couldn’t fit into the available classrooms, and classes started to meet in different corners of the sanctuary. Finally, under the leadership of board chairman Sol Singer, Shearith Israel, now numbering 124 member households, raised money for a new $150,000 building on Wynnton Road. The new sanctuary could seat 300 people; the synagogue also included a smaller chapel, a social room, a kitchen, and six classrooms. When Shearith Israel dedicated their new synagogue in February of 1951, Columbus Mayor B.F. Register cut the ribbon and Rabbi Alfred Goodman of B’nai Israel gave the opening prayer. Rabbi Jacob Agus of Baltimore gave the keynote address in a ceremony that included the singing of both “America” and “Hatikvah,” the Israeli national anthem.

As Shearith Israel moved into their new building, they also moved away from Orthodox Judaism. Through the 1940s, Shearith Israel was still Orthodox, with separate seating for men and women in the sanctuary and a mikvah (Jewish ritual bath). Many members still walked to shul. In 1949, the congregation celebrated its first bat mitzvah ceremony, in which a 13-year-old girl celebrated the coming of age ritual traditionally performed by boys. In 1950, their new rabbi, Emanuel Bennet, instituted mixed-gender seating and introduced some English into the Shabbat service. In 1952, under the leadership of newly hired Rabbi Kassel Abelson, Shearith Israel officially joined the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism. That same year, the congregation celebrated its first confirmation ceremony. Although Shearith Israel had officially become Conservative, the congregation still maintained some traditional practices, including daily minyans and a strictly kosher kitchen. Each male member was assigned monthly minyan duty, in which he would be responsible for getting ten men to attend that day’s prayer meeting. In 1974, under the leadership of Rabbi Theodore Feldman, Shearith Israel granted full equality to female members, allowing them to receive Torah honors and count towards the minyan. In the 1980s, Shearith Israel reached a peak of 150 families and continued to hold daily minyans. The congregation also had a kosher meat co-op, in which 30 members banded together to order kosher meat from Chicago and Atlanta several times a year.

B’nai Israel, now known as Temple Israel, also thrived in the years after World War II. In 1940, 80 families belonged to the Reform congregation; this figure grew to 119 in 1962 and peaked at 182 in 1982. Like Shearith Israel, Temple Israel outgrew its building. Just as they had done in 1885, the women of the congregation led the way: in 1952, the Jewish Ladies Aid Society passed a resolution labeling their current temple inadequate and calling for the construction of a new synagogue. Finally, in 1957, Temple Israel broke ground on a new synagogue on Wildwood Avenue. When they dedicated the building the following year, they led a procession with the Torahs from the old temple to the new one. Rabbi William Silverman from Nashville’s Ohabai Sholom congregation was the keynote speaker during the dedication which drew 350 people. This move to their new home took place during the long tenure of Rabbi Alfred Goodman, who led Temple Israel from 1950 to 1983.

While the Columbus Jewish community remained divided into two congregations, they united to help Jews in need. In 1939, Columbus Jews worked to bring in Jewish refugees from Germany. Victor Kiralfy was chairman of a coordinating committee that tried to bring a refugee family to Columbus every month, until the war made it impossible. Simon and Ruth Schwob also played a leading role in these efforts. Simon Schwob led the way in organizing the Columbus Jewish Welfare Federation in 1944. Their organizing meeting was held in Schwob’s office, and the clothing manufacturer served as the federation’s first president. During Israel’s 1967 War, the federation conducted an emergency fund drive which raised $110,000 for the Jewish state. When Israel was attacked on Yom Kippur in 1973, the Columbus Jewish Welfare Federation raised $170,000 for the Israeli war effort. In the 1960s, Shearith Israel started a nursery school for the children of the congregation. Later, the school became a Jewish community nursery school under the auspices of the Jewish Welfare Federation. The school closed in 1989.

Temple Israel Religious School

Temple Israel Religious School

Working Together

While Shearith Israel and Temple Israel remain separate viable congregations, they have often worked together for the betterment of local Jews and the larger community. They both joined the Wynnton Neighborhood Network, an association of six area churches that worked to help the needy. In 1984, Temple Israel established a food bank with St. Thomas Episcopal Church. After a year at Temple Israel, the project moved to the church, which had more room. In 1977, the two Jewish congregations merged their 8th, 9th, and 10th grade religious school classes. Rabbi Goodman of Temple Israel and Rabbi Feldman of Shearith Israel worked together to teach these classes along with members of both congregations. In the early 1990s, both religious schools were shrinking, and they decided to merge them completely. According to Jean Kiralfy Kent, a member of Temple Israel, “the path has not always been smooth, but the school has endured for the betterment of our children.”

Initially, this merger was a great success, as the total enrollment in the school increased. But soon this cooperation failed, and the schools split apart in 2004, as both congregations have suffered declining membership. In 2008, there were 45 children in Temple Israel's Sunday School, while Shearith Israel did not have a religious school. In 2009, Temple Israel was down to 115 families while Shearith Israel had started taking out ads in the Atlanta Jewish Times newspaper inviting unaffiliated Jews in the region to spend the High Holidays in Columbus. In 2009, Shearith Israel sold its building to a local church since its mostly elderly membership could not use the building, which was not accessible to people with disabilities. After the sale, the remaining 80 members met in the chapel at Temple Israel and began looking for a new permanent home. In 2010, Shearith Israel remodeled their parsonage house into a small synagogue and hired Rabbi Brian Glusman to be their part-time spiritual leader. In 2011, about 60 households belonged to the Conservative congregation.

While Shearith Israel and Temple Israel remain separate viable congregations, they have often worked together for the betterment of local Jews and the larger community. They both joined the Wynnton Neighborhood Network, an association of six area churches that worked to help the needy. In 1984, Temple Israel established a food bank with St. Thomas Episcopal Church. After a year at Temple Israel, the project moved to the church, which had more room. In 1977, the two Jewish congregations merged their 8th, 9th, and 10th grade religious school classes. Rabbi Goodman of Temple Israel and Rabbi Feldman of Shearith Israel worked together to teach these classes along with members of both congregations. In the early 1990s, both religious schools were shrinking, and they decided to merge them completely. According to Jean Kiralfy Kent, a member of Temple Israel, “the path has not always been smooth, but the school has endured for the betterment of our children.”

Initially, this merger was a great success, as the total enrollment in the school increased. But soon this cooperation failed, and the schools split apart in 2004, as both congregations have suffered declining membership. In 2008, there were 45 children in Temple Israel's Sunday School, while Shearith Israel did not have a religious school. In 2009, Temple Israel was down to 115 families while Shearith Israel had started taking out ads in the Atlanta Jewish Times newspaper inviting unaffiliated Jews in the region to spend the High Holidays in Columbus. In 2009, Shearith Israel sold its building to a local church since its mostly elderly membership could not use the building, which was not accessible to people with disabilities. After the sale, the remaining 80 members met in the chapel at Temple Israel and began looking for a new permanent home. In 2010, Shearith Israel remodeled their parsonage house into a small synagogue and hired Rabbi Brian Glusman to be their part-time spiritual leader. In 2011, about 60 households belonged to the Conservative congregation.

The Jewish Community in Columbus Today

The Jewish population of Columbus declined from approximately 1,000 people in 1984 to 750 in 2001. The numbers are likely lower today. While Columbus has long been overshadowed by the surging Jewish metropolis of Atlanta, it remains a historic and active center of Jewish life in Georgia.