Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Helena, Arkansas

Overview

Helena, Arkansas, grew up next to the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Crowley’s Ridge in Phillips County. The town dates to 1820, and it incorporated under the name “Helena” in 1833. As settlers and enslaved workers drained and cleared nearby lowlands for cotton production, Helena became a significant steamboat stop and trading hub. The town grew during the late 19th century, and an adjacent municipality, West Helena, incorporated along the railroad tracks in 1917. The two cities eventually merged to create Helena-West Helena in 2006.

Jewish settlers arrived in the Helena area in the 1840s, and an organized Jewish community emerged in the 1860s. A number of Jewish individuals and families became prominent among the town’s economic and civic elite, and local Jews enjoyed a relatively high level of acceptance in white, Christian society. The overall population in and around Helena began a long decline around 1950, however, and the local Jewish community dwindled to a handful of residents by the early 21st century.

Jewish settlers arrived in the Helena area in the 1840s, and an organized Jewish community emerged in the 1860s. A number of Jewish individuals and families became prominent among the town’s economic and civic elite, and local Jews enjoyed a relatively high level of acceptance in white, Christian society. The overall population in and around Helena began a long decline around 1950, however, and the local Jewish community dwindled to a handful of residents by the early 21st century.

Early Jewish Settlers

A small community of Jews migrants had made homes in Helena and the surrounding area by the mid-1840s; they even borrowed a Torah scroll from Congregation B’nai Israel in Cincinnati in order to hold high holiday services in 1846. Although details about these earliest arrivals are scarce, they likely fit the pattern of other Jews who settled along the Mississippi River and its tributaries: immigrants from Central Europe who made their living as traders in emerging market towns. Few, if any, of the Jewish residents from the 1840s made permanent homes in Helena, reflecting the high level of Jewish mobility in frontier communities.

Phillips County grew considerably during the 1850s as property owners imported a large population of enslaved Black workers to clear land and grow cotton. The county population stood at nearly 15,000 individuals by 1860, a majority of whom were enslaved. That agricultural growth fueled Helena’s development as a trading center and set the stage for an increase in Jewish settlers in subsequent decades.

A nucleus of more permanent Jewish residents arrived in Helena in the 1860s. These newcomers primarily came from Prussia or the German states, and they initially made their livings in trade. Henry Fink, for example, was born in Prussia (likely the town of Miłosław, now in Poland) around 1831 and emigrated at a young age. After spending time in New Jersey and St. Louis, Fink opened a mercantile business in Helena during the Civil War, reportedly in 1862. The Jewish community established a burial site around the time of Fink’s arrival but did not found a synagogue until after the end of the war. By the end of the decade, Jewish businesses played a significant role in local commercial life, and several long-term Jewish families—the Mundts, Solomons, and Triebers, in addition to the Finks—had settled in Helena.

Phillips County grew considerably during the 1850s as property owners imported a large population of enslaved Black workers to clear land and grow cotton. The county population stood at nearly 15,000 individuals by 1860, a majority of whom were enslaved. That agricultural growth fueled Helena’s development as a trading center and set the stage for an increase in Jewish settlers in subsequent decades.

A nucleus of more permanent Jewish residents arrived in Helena in the 1860s. These newcomers primarily came from Prussia or the German states, and they initially made their livings in trade. Henry Fink, for example, was born in Prussia (likely the town of Miłosław, now in Poland) around 1831 and emigrated at a young age. After spending time in New Jersey and St. Louis, Fink opened a mercantile business in Helena during the Civil War, reportedly in 1862. The Jewish community established a burial site around the time of Fink’s arrival but did not found a synagogue until after the end of the war. By the end of the decade, Jewish businesses played a significant role in local commercial life, and several long-term Jewish families—the Mundts, Solomons, and Triebers, in addition to the Finks—had settled in Helena.

Organized Jewish Life

Jewish congregational life in Helena officially commenced in 1866, when 65 Jewish men established the United Hebrew Congregation. The group drew members from beyond Helena and included households in Lee and Munrow Counties (north and northwest of Phillips County). Whereas the congregation initially intended to conduct services “in the Polish orthodox style,” local resident L. Selig (himself a native of Poland) prevailed in convincing the membership to adopt Minhag America, the Reform prayer book developed by Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise.

The United Hebrew Congregation initially worshiped in members’ homes, and they later rented space in a storeroom on Ohio Street and then in a former church. By 1875, the congregation became known as Beth El. They officially joined the Reform movement and established a new cemetery that year, as well. (The congregation moved several of the earlier burials to the new site, and the exact location of the original cemetery is unknown.)

As the congregation grew, they began to consider building a synagogue. They shared a building for a time with a Methodist congregation under the leadership of Reverend L. Garrison, who took it upon himself to recruit ten of Helena’s unaffiliated Jewish men to Beth El. (There were reportedly 41 Jewish men in town at the time, only 21 of whom belonged to Beth El before Garrison’s membership push.) Congregants reportedly committed themselves to the construction of their own building in January 1880 at the wedding of Charlie Meyers and Celia Weinlaub. They dedicated a brick building at the corner of Perry and Pecan Streets that October. Rabbi Max Samfield from Memphis’s Temple Israel was the featured guest, reflecting strong connections between Memphis and many of the small, nearby communities in Arkansas and other states. Reverend Garrison also attended the dedication ceremony; although Beth El invited several local ministers, he was the only Christian clergy to attend.

The United Hebrew Congregation initially worshiped in members’ homes, and they later rented space in a storeroom on Ohio Street and then in a former church. By 1875, the congregation became known as Beth El. They officially joined the Reform movement and established a new cemetery that year, as well. (The congregation moved several of the earlier burials to the new site, and the exact location of the original cemetery is unknown.)

As the congregation grew, they began to consider building a synagogue. They shared a building for a time with a Methodist congregation under the leadership of Reverend L. Garrison, who took it upon himself to recruit ten of Helena’s unaffiliated Jewish men to Beth El. (There were reportedly 41 Jewish men in town at the time, only 21 of whom belonged to Beth El before Garrison’s membership push.) Congregants reportedly committed themselves to the construction of their own building in January 1880 at the wedding of Charlie Meyers and Celia Weinlaub. They dedicated a brick building at the corner of Perry and Pecan Streets that October. Rabbi Max Samfield from Memphis’s Temple Israel was the featured guest, reflecting strong connections between Memphis and many of the small, nearby communities in Arkansas and other states. Reverend Garrison also attended the dedication ceremony; although Beth El invited several local ministers, he was the only Christian clergy to attend.

As the congregation moved into its first synagogue, it also sought to hire its first clergy. Reverend Dr. Abraham Myer (or Meyers) held the position for a short stint that ended in 1881. (American Jewish clergy often used the title of “reverend” at the time.) The search for stable rabbinical services remained a challenge for Beth El well into the 20th century, and the community employed 21 rabbis between approximately 1880 and 1960. While Myers apparently left the rabbinate at the conclusion of his employment in Helena, other local rabbis often arrived fresh out of rabbinical school and soon departed for more prominent pulpits. Whenever Beth El found itself without a rabbi, the congregation relied on visiting clergy from nearby towns and cities or student rabbis from Hebrew Union College.

In addition to Beth El, local Jewish men established a chapter of the national fraternal organization B’nai B’rith in 1871. The community briefly supported a Young Men’s Hebrew Association and established a longer lasting social organization known as the Lotus Club by 1895. Although Helena Jews enjoyed a relatively high level of acceptance in white, Christian society, they maintained the Lotus Club as a primarily Jewish social space until at least the 1940s. The women of Beth El founded a Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Association in 1875, which played a major role in the development of the congregation in addition to offering philanthropic support to a variety of causes.

In addition to Beth El, local Jewish men established a chapter of the national fraternal organization B’nai B’rith in 1871. The community briefly supported a Young Men’s Hebrew Association and established a longer lasting social organization known as the Lotus Club by 1895. Although Helena Jews enjoyed a relatively high level of acceptance in white, Christian society, they maintained the Lotus Club as a primarily Jewish social space until at least the 1940s. The women of Beth El founded a Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Association in 1875, which played a major role in the development of the congregation in addition to offering philanthropic support to a variety of causes.

Civic and Social Life

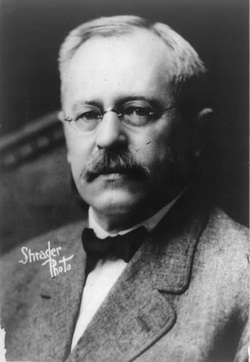

Judge Jacob Trieber.

Judge Jacob Trieber.

The founding and development of Beth El coincided with a period of significant growth in Helena and Phillips County. As the community grew, several Jewish families became prominent leaders in business and civic affairs. Aaron Meyers, for instance served the city as tax collector, treasurer and, from 1878 to 1880, mayor. Henry Fink’s son Jacob served as a mayor, judge, and school board member in the early 20th century.

Helena’s most notable Jewish officeholder was Jacob Trieber, the first Jew ever appointed as a federal judge in the United States. Born in 1853 in the small town of Raszków in Polish Prussia, Trieber first settled in Helena in 1868, where he initially worked as a clerk in a retail store. Over time he became a well-respected lawyer and civic leader, serving as a city councilman and county treasurer. He moved to Little Rock in 1897 after earning an appointment as a U.S. district attorney, and in 1900 President William McKinley named him a federal court judge.

Moses (sometimes Charles) Solomon arrived in or around 1863. He was a native of Hamberg. In 1866 he married Pauline Potsdamer, who was born in Lissa, Prussia (eventually Leszno, Poland). Moses and Pauline raised eight children in Helena. Joseph Solomon started in the grocery business and later entered the cotton industry; Philip Solomon co-founded a dry goods store that grew into the largest department store in town; and David Solomon ran a clothing store known as The Leader and operated a wholesale business with their brother Lafe. The Solomons were also related by marriage to other local Jewish families, including the Weinlaubs and the Meyerses.

Oral histories and other records indicate that Helena Jews experienced minimal antisemitism, and a variety of evidence supports that generalization. In 1903, the local newspaper described Helena’s Jews, writing: “in character, in wealth, and in influence, the Hebrews of Helena will compare favorably with those of any other city, large or small, in this country...they are almost to a man valuable citizens and upright gentlemen.”Jewish officeholders in the early 20th century included David Solomon, who served on the school board and even defeated a Ku Klux Klan-backed challenger during the 1920s, peak years for Klan power in Arkansas and across the country. Additionally, the local country club accepted Jewish members from the time of its inception in 1909. Despite a general atmosphere of acceptance and social integration, elite high school fraternities and sororities did exclude Jewish youth during the early 20th century.

Helena’s most notable Jewish officeholder was Jacob Trieber, the first Jew ever appointed as a federal judge in the United States. Born in 1853 in the small town of Raszków in Polish Prussia, Trieber first settled in Helena in 1868, where he initially worked as a clerk in a retail store. Over time he became a well-respected lawyer and civic leader, serving as a city councilman and county treasurer. He moved to Little Rock in 1897 after earning an appointment as a U.S. district attorney, and in 1900 President William McKinley named him a federal court judge.

Moses (sometimes Charles) Solomon arrived in or around 1863. He was a native of Hamberg. In 1866 he married Pauline Potsdamer, who was born in Lissa, Prussia (eventually Leszno, Poland). Moses and Pauline raised eight children in Helena. Joseph Solomon started in the grocery business and later entered the cotton industry; Philip Solomon co-founded a dry goods store that grew into the largest department store in town; and David Solomon ran a clothing store known as The Leader and operated a wholesale business with their brother Lafe. The Solomons were also related by marriage to other local Jewish families, including the Weinlaubs and the Meyerses.

Oral histories and other records indicate that Helena Jews experienced minimal antisemitism, and a variety of evidence supports that generalization. In 1903, the local newspaper described Helena’s Jews, writing: “in character, in wealth, and in influence, the Hebrews of Helena will compare favorably with those of any other city, large or small, in this country...they are almost to a man valuable citizens and upright gentlemen.”Jewish officeholders in the early 20th century included David Solomon, who served on the school board and even defeated a Ku Klux Klan-backed challenger during the 1920s, peak years for Klan power in Arkansas and across the country. Additionally, the local country club accepted Jewish members from the time of its inception in 1909. Despite a general atmosphere of acceptance and social integration, elite high school fraternities and sororities did exclude Jewish youth during the early 20th century.

As accepted members of white society, Helena Jews both participated in and benefitted from the racial hierarchy that structured local life. Like their white, non-Jewish peers, middle-class Jewish households employed Black domestic workers as cooks, maids, and chauffeurs, and Jewish-owned stores hired Black workers for menial jobs. Jewish landowners and cotton traders profited from the labor of sharecroppers and tenant farmers in a system that provided few opportunities for Black workers to earn middle class livings.

The aftermath of the 1919 Elaine Massacre, in which white vigilantes and federal troops killed an unknown number of Black residents of Phillips County, provides the most explicit example of Jewish complicity in the white supremacist system. While none of the white attackers faced legal consequences for their actions, local officials prosecuted twelve Black men for allegedly organizing a Black labor uprising. Former mayor and Helena lawyer Jacob Fink served as the court-appointed defense attorney for Frank Hicks, one of the “Elaine Twelve,” but Fink failed to offer even an anemic defense. He did not challenge any of the (all white) jurors, did not call any witnesses, and did not offer a closing argument. As part of the local white elite, his role was merely to ensure that Hicks (like the other accused men) received a guilty verdict and a death sentence.

Whereas Jacob Fink seems to have identified thoroughly with the cause of white supremacy, other Helena Jews held progressive views on race. Most significantly, former Helena resident Judge Jacob Trieber issued several rulings that affirmed Black civil and economic rights, and he publicly promoted suffrage for Black citizens and women alike. When the Elaine Massacre case came before his court in 1921, Trieber recused himself based on his personal connection to Helena, but not before offering a crucial stay of execution that allowed the defendants’ appeal to receive a federal hearing. Trieber also connected his views on anti-Black racism to his childhood experiences in Prussia, where he witnessed anti-Jewish discrimination firsthand.

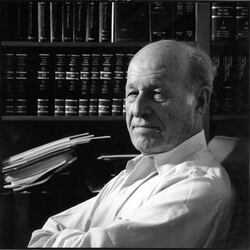

Judge Trieber was not the only Jewish resident of Helena to exhibit progressive views on race, although his actions were more public. From the mid-20th century until the early 21st, David and Miriam Solomon maintained their family’s philanthropic and civic legacy, and quietly supported several causes related to Black advancement. Miriam, for example, served on the board of the Eastern Arkansas Regional Mental Health Center, one of the first local community organizations to draw together an integrated board.

The aftermath of the 1919 Elaine Massacre, in which white vigilantes and federal troops killed an unknown number of Black residents of Phillips County, provides the most explicit example of Jewish complicity in the white supremacist system. While none of the white attackers faced legal consequences for their actions, local officials prosecuted twelve Black men for allegedly organizing a Black labor uprising. Former mayor and Helena lawyer Jacob Fink served as the court-appointed defense attorney for Frank Hicks, one of the “Elaine Twelve,” but Fink failed to offer even an anemic defense. He did not challenge any of the (all white) jurors, did not call any witnesses, and did not offer a closing argument. As part of the local white elite, his role was merely to ensure that Hicks (like the other accused men) received a guilty verdict and a death sentence.

Whereas Jacob Fink seems to have identified thoroughly with the cause of white supremacy, other Helena Jews held progressive views on race. Most significantly, former Helena resident Judge Jacob Trieber issued several rulings that affirmed Black civil and economic rights, and he publicly promoted suffrage for Black citizens and women alike. When the Elaine Massacre case came before his court in 1921, Trieber recused himself based on his personal connection to Helena, but not before offering a crucial stay of execution that allowed the defendants’ appeal to receive a federal hearing. Trieber also connected his views on anti-Black racism to his childhood experiences in Prussia, where he witnessed anti-Jewish discrimination firsthand.

Judge Trieber was not the only Jewish resident of Helena to exhibit progressive views on race, although his actions were more public. From the mid-20th century until the early 21st, David and Miriam Solomon maintained their family’s philanthropic and civic legacy, and quietly supported several causes related to Black advancement. Miriam, for example, served on the board of the Eastern Arkansas Regional Mental Health Center, one of the first local community organizations to draw together an integrated board.

Jewish Life in the 20th Century

Attorney David Solomon, c. 1990. Photograph by Bill Aron.

Attorney David Solomon, c. 1990. Photograph by Bill Aron.

Helena continued to attract Jewish migrants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including new arrivals with roots in Eastern Europe. Brothers Joe and Sam Ciener, for example, came from Hungary, and Sam became a successful men’s clothier as the owner of The Stag. He also served on the local school board for twelve years. Barnett (Barney) and Rose Cohen both came from Russia and had settled in Arkansas by about 1904. Their path to Helena included stopovers in London and Little Rock, and in Helena they ran a produce business. Between longstanding families and newcomers, Helena boasted 22 Jewish owned businesses in 1909, a significant number for a community of under 9,000 residents.

Temple Beth El (as the congregation was known by the 1890s) grew with the local population, but retaining full-time clergy continued to prove difficult. In 1900 they hired Rabbi Abram Brill, a recent graduate of Hebrew Union College (HUC), to be their full-time rabbi for $1,500 a year. Rabbi Brill was quite popular, and he was unanimously reelected by the congregation in 1901. The following year, however, he accepted an invitation to assume the pulpit at the much larger congregation in Greenville, Mississippi. Rabbi Brill did help the congregation to hire a fresh HUC graduate to replace him—a challenging task, since the graduating class at HUC in those days was usually ten men. This national shortage of qualified clergy contributed to frequent turnover at Temple Beth El.

Jewish lay people in Helena seem to have retained a notable level of control over religious ritual, perhaps due to the rabbinical revolving door at Temple Beth El. When Rabbi Aaron Weinstein arrived in 1909, just after his ordination, he was informed by the temple’s Ritual Committee that his sermons could not exceed fifteen minutes. Apparently, he followed these orders, as he became quite popular with the congregation. Temple Beth El extended his contract and increased his salary in 1912, but he resigned to take another pulpit just a few months later. When his replacement, Rabbi Samuel Peiper requested that the full congregation rise together for the Kaddish, the prayer for mourning the dead, they refused to change their ritual practice.

Temple Beth El (as the congregation was known by the 1890s) grew with the local population, but retaining full-time clergy continued to prove difficult. In 1900 they hired Rabbi Abram Brill, a recent graduate of Hebrew Union College (HUC), to be their full-time rabbi for $1,500 a year. Rabbi Brill was quite popular, and he was unanimously reelected by the congregation in 1901. The following year, however, he accepted an invitation to assume the pulpit at the much larger congregation in Greenville, Mississippi. Rabbi Brill did help the congregation to hire a fresh HUC graduate to replace him—a challenging task, since the graduating class at HUC in those days was usually ten men. This national shortage of qualified clergy contributed to frequent turnover at Temple Beth El.

Jewish lay people in Helena seem to have retained a notable level of control over religious ritual, perhaps due to the rabbinical revolving door at Temple Beth El. When Rabbi Aaron Weinstein arrived in 1909, just after his ordination, he was informed by the temple’s Ritual Committee that his sermons could not exceed fifteen minutes. Apparently, he followed these orders, as he became quite popular with the congregation. Temple Beth El extended his contract and increased his salary in 1912, but he resigned to take another pulpit just a few months later. When his replacement, Rabbi Samuel Peiper requested that the full congregation rise together for the Kaddish, the prayer for mourning the dead, they refused to change their ritual practice.

In 1916, the congregation completed work on its second and final building, which featured a $4,000 organ paid for by the congregation’s Ladies Benevolent Association. The association had long played an important role in supporting Temple Beth El. In 1904, they paid to add indoor toilets to the synagogue. The next year, when the temple needed a new roof, the Ladies’ Benevolent Association paid for it themselves. When Beth El moved to their new synagogue in 1916, a significant portion of the cost was borne by the Ladies Association.

In addition to serving Jews in Helena, Beth El was a regional congregation that attracted Jews from such smaller towns as Marianna, Marvell, Holly Grove, Trenton, and West Helena. In 1904, Jews in Marianna asked whether Beth El’s rabbi could lead services there once a month; the temple board agreed as long as they became dues-paying members of Beth El, which they did. This regional nature of the congregation is apparent in the window memorials in the main sanctuary. One was donated by the Jewish citizens of Marianna, one by those in Marvell, and another by a member who lived in Marks, Mississippi.

In addition to serving Jews in Helena, Beth El was a regional congregation that attracted Jews from such smaller towns as Marianna, Marvell, Holly Grove, Trenton, and West Helena. In 1904, Jews in Marianna asked whether Beth El’s rabbi could lead services there once a month; the temple board agreed as long as they became dues-paying members of Beth El, which they did. This regional nature of the congregation is apparent in the window memorials in the main sanctuary. One was donated by the Jewish citizens of Marianna, one by those in Marvell, and another by a member who lived in Marks, Mississippi.

The Decline of Jewish Helena

Helena was never a large Jewish community. Four hundred Jews reportedly lived there in 1927, but that number (which may have been exaggerated) declined in subsequent decades. At the time of Temple Beth El’s centennial in 1967, the congregation claimed 68 households represented by 109 adult members. Despite the challenges of a shrinking Jewish community, the congregation remained active throughout the twentieth century. Latvian-born Rabbi Samuel Shillman assumed the pulpit in 1960 after serving a handful of other southern congregations, and he became Helena’s final (and possibly longest tenured) full-time rabbi by remaining until his death in 1977. Rabbi James Wax, retired from Temple Israel in Memphis, subsequently provided monthly visits until 1989.

The fate of Jewish Helena mirrored that of similar small-town communities in and beyond the South. As the cotton economy changed in the early and mid-20th century, local agricultural workers migrated to larger cities to seek industrial employment, which led the Phillips County population to a long period of decline around 1950. Jewish families continued to own a number of significant businesses into the 1970s and 1980s, but Jewish children raised in the area tended to leave for college and did not return.

By the early 20th century, Temple Beth El’s local membership had fallen to fewer than twenty. (Some former Helena residents maintained memberships after relocating.) In 2006, 139 years after the congregation’s founding, Temple Beth El’s remaining members came to the difficult decision to close their building. Many of the artifacts from Temple Beth El went to the recently formed Congregation Etz Chaim in Bentonville, Arkansas, and the pulpit furnishings went to Temple Israel in Memphis for use at their cemetery chapel. They donated the Temple El building, which was the oldest Arkansas synagogue still in use at that time, to the state for use as a community arts center.

The fate of Jewish Helena mirrored that of similar small-town communities in and beyond the South. As the cotton economy changed in the early and mid-20th century, local agricultural workers migrated to larger cities to seek industrial employment, which led the Phillips County population to a long period of decline around 1950. Jewish families continued to own a number of significant businesses into the 1970s and 1980s, but Jewish children raised in the area tended to leave for college and did not return.

By the early 20th century, Temple Beth El’s local membership had fallen to fewer than twenty. (Some former Helena residents maintained memberships after relocating.) In 2006, 139 years after the congregation’s founding, Temple Beth El’s remaining members came to the difficult decision to close their building. Many of the artifacts from Temple Beth El went to the recently formed Congregation Etz Chaim in Bentonville, Arkansas, and the pulpit furnishings went to Temple Israel in Memphis for use at their cemetery chapel. They donated the Temple El building, which was the oldest Arkansas synagogue still in use at that time, to the state for use as a community arts center.

Updated March 2024.