Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Texarkana, Texas

Historical Overview

Just south of where the Red River crosses from northeast Texas into southwest Arkansas sits Texarkana, a city split by the state line. Texarkana was established in 1873 at the junction of the Cairo and Fulton Railroad, which crossed through Arkansas, and the Texas and Pacific Railway, which ran east-west through Texas. Although the city actually consists of two municipalities, the two sides of Texarkana share a water system, a criminal justice building, and a common history. From its beginning as a small rail hub, Texarkana developed quickly during the 1890s, when each section installed water, gas, and electrical facilities and industry sprung up on both sides of the state line. Until the Great Depression, jobs with the railroads or in the agricultural processing industries attracted workers to Texarkana.

The Jewish community in Texarkana formed shortly after the city’s founding and proved instrumental in the town’s development and growth. Jewish residents began to meet together for prayer services during the 1870s, and Jewish institutions took root the following decade. While the Jewish community grew during the early 20th century and thrived in the aftermath of World War II, the city’s Jewish population declined in the late 20th century. Texarkana’s historical Reform congregation, Mount Sinai, closed its doors in 2015.

The Jewish community in Texarkana formed shortly after the city’s founding and proved instrumental in the town’s development and growth. Jewish residents began to meet together for prayer services during the 1870s, and Jewish institutions took root the following decade. While the Jewish community grew during the early 20th century and thrived in the aftermath of World War II, the city’s Jewish population declined in the late 20th century. Texarkana’s historical Reform congregation, Mount Sinai, closed its doors in 2015.

Early Jewish Settlers

In the last quarter of the 19th century, Jews began to settle in the newly formed Texarkana. Joseph Deutschmann, who was born in Poland according to the 1880 census, arrived in the early 1870s and made his living in real estate. He helped the development of water and gas companies in Texarkana, owned a stake in the city’s first streetcars, and developed housing in the growing town. When a flood in 1874 destroyed an African American residential area he had built, Deutschmann constructed a drainage system known as “Deutschmann’s Canal.”

The majority of Jewish migrants worked in retail selling dry goods and clothing. Abram Erber and Abram Goldberg, both born in Poland, and Russian-immigrant Solomon Davidson owned dry goods stores. Abraham J. Hoffman, born in Austria, was a clothes merchant, and by 1883 Marks Kosminsky, born in Russia, owned and ran a general store with his brother Joseph. Other prominent early Jews included clothing merchant Sam Heilbron, bankers Joseph Marx and Leon Rosenberg, Confederate Army veteran Bero Berlinger, and café owner Martin Levy.

The majority of Jewish migrants worked in retail selling dry goods and clothing. Abram Erber and Abram Goldberg, both born in Poland, and Russian-immigrant Solomon Davidson owned dry goods stores. Abraham J. Hoffman, born in Austria, was a clothes merchant, and by 1883 Marks Kosminsky, born in Russia, owned and ran a general store with his brother Joseph. Other prominent early Jews included clothing merchant Sam Heilbron, bankers Joseph Marx and Leon Rosenberg, Confederate Army veteran Bero Berlinger, and café owner Martin Levy.

Upon visiting Texarkana in 1879, Jewish newspaper editor Charles Wessolowsky found ten Jewish families, around 75 people, who had little organization and a curious situation regarding their spiritual leadership. Reverend Charles Goldberg, pastor of a local church, was trained as a rabbi in Germany but became an ordained minister after falling ill and being nursed back to health by a Presbyterian family in Missouri in the 1840s. Without a qualified leader for the 1876 High Holiday services, Texarkana’s Jews asked Reverend Goldberg to officiate. Goldberg must have continued performing the High Holiday services through the late 1870s as, in 1879, Wessolowsky described Goldberg as a “hypocrite” with “hidden selfish motives,” though Goldberg never attempted to convert Texarkana’s Jews to Christianity. On his deathbed, Goldberg asked for a rabbi and even requested that he be buried in the Jewish cemetery.

Organized Jewish Life

Other than the High Holiday services conducted by Reverend Goldberg and reported on by Wessolowsky, the early record of Jewish celebrations is sparse; Texarkana’s newspaper records only date back to 1884. The earliest documented High Holiday services in Texarkana were held in 1885, though services most likely took place through the early 1880s as well, probably in Kosminsky Hall, the Masonic Hall built above one of Marks Kosminsky’s store houses. Rabbi Friedman of Camden, Arkansas, presided over services in 1885 with help from Marks Kosminsky. That year the Daily Texarkana Independent wrote: “Tomorrow is the Jewish New Year, and all our citizens of that faith will close their business houses from 6 o’clock this evening until 6pm tomorrow.”

Although the exact timing is unclear, records suggest that Mount Sinai Congregation was formed around 1885, and a Jewish cemetery, Mount Sinai Memorial Park, was likely purchased that same year. An April 1885 newspaper announced monthly meetings of the Texarkana Hebrew Benevolent Association in Kosminsky Hall, with Joseph Deutschmann serving as president. By July 1886 meetings were held twice a month. In 1888 the women of the community established the Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Society, which gave charity to those in need and maintained the cemetery. In 1900, the society had 21 members. Later, the group became the Mount Sinai Sisterhood and remained extremely active in the congregation for years to come.

Although the exact timing is unclear, records suggest that Mount Sinai Congregation was formed around 1885, and a Jewish cemetery, Mount Sinai Memorial Park, was likely purchased that same year. An April 1885 newspaper announced monthly meetings of the Texarkana Hebrew Benevolent Association in Kosminsky Hall, with Joseph Deutschmann serving as president. By July 1886 meetings were held twice a month. In 1888 the women of the community established the Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Society, which gave charity to those in need and maintained the cemetery. In 1900, the society had 21 members. Later, the group became the Mount Sinai Sisterhood and remained extremely active in the congregation for years to come.

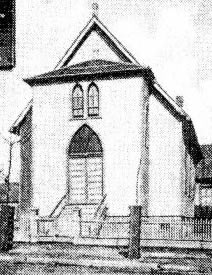

Mount Sinai's second synagogue, dedicated in 1894.

Mount Sinai's second synagogue, dedicated in 1894.

After Mount Sinai Congregation was founded in the mid-1880s, the congregation’s president, Joseph Deutschmann, sought to acquire a synagogue building. An Episcopal Church was for sale and Deutschmann—with the help of his non-Jewish friend Fred Offenhauser—purchased it, had it moved to Eighth Street and State Line Avenue on the Arkansas side of Texarkana, and remodeled it into a synagogue. Misfortune struck in 1892 when a grocery store adjacent to the synagogue caught fire and the congregation’s new home burned down. The congregation dedicated a new synagogue 1894, however, built at Fourth and Walnut Streets in Arkansas. In October 1893 Mount Sinai’s thirty members (adult men) adopted a constitution for the congregation. Around the same time, the congregation hired its first rabbi, A. Shriber. As of 1900, a Rabbi Kaiser led the congregation. The city’s overall population rose from 14,000 in 1896 to around 21,000 in 1925, and Mount Sinai’s membership grew as well. The congregation claimed 50 households in 1917.

With its English name and use of English prayers, Mount Sinai Congregation was Reform from its founding, though it did not consistently affiliate with the Reform Movement. In 1907, Mount Sinai belonged to the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (UAHC, later the Union for Reform Judaism), though this membership was short-lived. Most likely, the congregation’s decision to disaffiliate was due to economic rather than religious or ideological reasons. In 1939 Mount Sinai officially rejoined the UAHC.

While some of Texarkana’s Jews were Orthodox in their traditions, their numbers were too small to form a separate congregation. Instead, they held their own separate Orthodox minyan early on Saturday mornings. Since the Orthodox group was so small, some Reform members attended the traditional service to help them have the ten men required for a minyan. By the 1940s, this Orthodox group had dwindled and the separate services were discontinued.

In addition to Mount Sinai Congregation, Texarkana Jews established other Jewish organizations. In 1901, they founded a B’nai B’rith Lodge for men; in 1947, Jewish women in Texarkana started a chapter of B’nai B’rith Women. Other early 20th century Jewish organizations in Texarkana include a Zionist association, founded in 1917, and the Jewish Charity Chest, founded in 1931 to help those in need during the Great Depression.

With its English name and use of English prayers, Mount Sinai Congregation was Reform from its founding, though it did not consistently affiliate with the Reform Movement. In 1907, Mount Sinai belonged to the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (UAHC, later the Union for Reform Judaism), though this membership was short-lived. Most likely, the congregation’s decision to disaffiliate was due to economic rather than religious or ideological reasons. In 1939 Mount Sinai officially rejoined the UAHC.

While some of Texarkana’s Jews were Orthodox in their traditions, their numbers were too small to form a separate congregation. Instead, they held their own separate Orthodox minyan early on Saturday mornings. Since the Orthodox group was so small, some Reform members attended the traditional service to help them have the ten men required for a minyan. By the 1940s, this Orthodox group had dwindled and the separate services were discontinued.

In addition to Mount Sinai Congregation, Texarkana Jews established other Jewish organizations. In 1901, they founded a B’nai B’rith Lodge for men; in 1947, Jewish women in Texarkana started a chapter of B’nai B’rith Women. Other early 20th century Jewish organizations in Texarkana include a Zionist association, founded in 1917, and the Jewish Charity Chest, founded in 1931 to help those in need during the Great Depression.

Civic and Economic Life

Simon Ehrlich

Simon Ehrlich

Several Jewish Texarkana residents became notable leaders in the local business community as Jewish owned establishments proliferated on East and West Broad Street in downtown Texarkana. Many Jews, such as Adolph and Morris Sandberger and Isaac Schwartz, ran dry goods stores. Gus Zimmerman, Sol Danziger, Benjamin Fane, and the Scherer brothers all made their livings in clothing retail or tailoring. Other Jewish businesses included Heilbron Jewelry and Leo Krouse’s Texarkana Casket Co.. A small number of Texarkana Jews worked in the professions. For example, Marks Kominsky’s son Leonce worked as a physician by 1910.

Texarkana Jews matched their involvement in economic life with civic service. Leo Krouse, born in Austria-Hungary, served as the president of the congregation as well as the local Board of Trade and ran war relief fundraising efforts during World War I. Theater owners Simon and Harry Ehrlich lived in Texarkana in the late 19th century before moving to Shreveport. They maintained an interest in Texarkana, however, operating a theater there and contributing to local philanthropies. East Prussia native and Spanish-American War veteran Louis Josephs was a successful local attorney. Joseph was elected to represent Miller County in the state legislature three times, beginning in 1913; later, he served as a Texarkana Municipal Court judge from 1925 to 1935.

Texarkana Jews matched their involvement in economic life with civic service. Leo Krouse, born in Austria-Hungary, served as the president of the congregation as well as the local Board of Trade and ran war relief fundraising efforts during World War I. Theater owners Simon and Harry Ehrlich lived in Texarkana in the late 19th century before moving to Shreveport. They maintained an interest in Texarkana, however, operating a theater there and contributing to local philanthropies. East Prussia native and Spanish-American War veteran Louis Josephs was a successful local attorney. Joseph was elected to represent Miller County in the state legislature three times, beginning in 1913; later, he served as a Texarkana Municipal Court judge from 1925 to 1935.

The Jewish Community in the 20th Century

Blessed with a strong membership base, Mount Sinai Congregation decided to enlarge its synagogue in the 1930s. Recent renovations had improved their building, but the growing community needed additional space. Economic conditions made this endeavor difficult, as even successful families found themselves unable to make large donations. Thanks to the zeal and generosity of Simon Ehrlich, however, Mount Sinai Congregation dedicated a newly constructed education building in his honor in 1935, the year of the congregation’s 50th anniversary.

The new addition proved well timed. Mount Sinai Congregation grew from approximately 40 families in 1940 to around 50 households at the end of the war. The upward trend resulted from the construction of the Lone Star Army Ammunition Plant and the Red River Army Depot just outside the city, which drew hundreds of new servicemembers to the area and provided an economic boost to the city as a whole. The newcomers included Jewish military personnel, as well, and Texarkana Jews—organized through the Jewish Welfare Board—hosted Jewish soldiers for holidays, Shabbat meals, and social occasions. The congregation invited servicemen, both Jewish and non-Jewish, to Friday night services and the social hour which followed. A few soldiers married young Jewish women from Texarkana and settled there after the war.

The new addition proved well timed. Mount Sinai Congregation grew from approximately 40 families in 1940 to around 50 households at the end of the war. The upward trend resulted from the construction of the Lone Star Army Ammunition Plant and the Red River Army Depot just outside the city, which drew hundreds of new servicemembers to the area and provided an economic boost to the city as a whole. The newcomers included Jewish military personnel, as well, and Texarkana Jews—organized through the Jewish Welfare Board—hosted Jewish soldiers for holidays, Shabbat meals, and social occasions. The congregation invited servicemen, both Jewish and non-Jewish, to Friday night services and the social hour which followed. A few soldiers married young Jewish women from Texarkana and settled there after the war.

Leo Walkow

Leo Walkow

Mount Sinai thrived in the early post-war era, when the area’s overall population surpassed 40,000 people. The congregation sold its 1894 building in 1946 and met at the Miller County Courthouse on Friday nights until the new facility was completed. They used the Congregational Church for high holiday services during that period. The congregation adopted a new constitution in 1948 and dedicated their new building (on the Texas side of the city) a year later. The Texarkana Gazette referred to the ceremony as one of “beauty, dignity, and prayer.” Jewish community leaders addressed the attendees, as did the president of the Texarkana Ministerial Alliance. The new facility featured a social hall, kitchen, rabbinical study, classroom, a 90-seat sanctuary.

The growing Jewish community included a number of newcomers. Leo and Madelyn Walkow, for instance, owned a dress shop and were active on the synagogue and sisterhood boards. Leo prepared many Jewish children for b’nai mitzvah over the years, and the congregation renamed its social hall in his honor in 1981. Congregants also came from small towns in the area; Jake and Hannah Meyers lived in Atlanta, Texas, while Ellen and Henry Kaufman lived in Ashdown, Arkansas.

The growing Jewish community included a number of newcomers. Leo and Madelyn Walkow, for instance, owned a dress shop and were active on the synagogue and sisterhood boards. Leo prepared many Jewish children for b’nai mitzvah over the years, and the congregation renamed its social hall in his honor in 1981. Congregants also came from small towns in the area; Jake and Hannah Meyers lived in Atlanta, Texas, while Ellen and Henry Kaufman lived in Ashdown, Arkansas.

Rabbi Joseph Levine

Rabbi Joseph Levine

Perhaps the most significant arrival to Mount Sinai in the mid-20th century was Rabbi Joseph Levine. Until the late 1950s a string of rabbis occupied the pulpit for short periods, with the longest serving clergy being Joseph Bogen (1900-1906), Rudolph Farber (1915-1922), David Alpert (1930-1935), and Moses Landau (1946-1950). Rabbi Levine, a native of McKeesport, Pennsylvania, served Mount Sinai from 1958 until 1981, however. Known for his excellent speaking skills and love of United States history, Rabbi Levine won the affection of his congregation and the respect of the wider community. He arrived during the heyday of congregational life, just two years after Mount Sinai had added three religious school classrooms to its building and a year before they installed air conditioning. In 1974 the congregation refurbished its cemetery and renamed it Mount Sinai Memorial Park. Members also established a perpetual care trust for the cemetery during this period. (Although Texarkana Jews general enjoyed a high level of acceptance and security, vandals did damage 27 monuments in 1980.)

Mt. Sinai initially thrived in the post-war era. By 1952, 40,490 people lived in Texarkana, and in the 1940s and 1950s many Jews chose to make Texarkana their new home. Among the new arrivals were Leo and Madelyn Walkow, who owned a dress shop. Both Leo and Madelyn were active in the congregation, serving on the temple and sisterhood boards. Leo prepared many of the synagogue’s youths for their b'nei mitzvah and in 1981 the social hall was renamed the Leo A. Walkow Hall in honor of his service to the congregation. The congregation also drew members from the small towns surrounding Texarkana. Jake and Hannah Meyers lived in Atlanta, Texas, while Ellen and Henry Kaufman lived in Ashdown, Arkansas.

Mt. Sinai initially thrived in the post-war era. By 1952, 40,490 people lived in Texarkana, and in the 1940s and 1950s many Jews chose to make Texarkana their new home. Among the new arrivals were Leo and Madelyn Walkow, who owned a dress shop. Both Leo and Madelyn were active in the congregation, serving on the temple and sisterhood boards. Leo prepared many of the synagogue’s youths for their b'nei mitzvah and in 1981 the social hall was renamed the Leo A. Walkow Hall in honor of his service to the congregation. The congregation also drew members from the small towns surrounding Texarkana. Jake and Hannah Meyers lived in Atlanta, Texas, while Ellen and Henry Kaufman lived in Ashdown, Arkansas.

Mount Sinai's 1949 synagogue

Mount Sinai's 1949 synagogue

Mount Sinai maintained a membership of approximately 40 households from its 75th anniversary in 1960 until the late 1980s. However, Jewish children raised in Texarkana during those decades tended to leave town for college and then settled in larger cities. Several adult members, including the Walkows, Zimmermans, and Wexlers, relocated during those years, as well, but a handful of newcomers balanced out the losses in the 1970s.

The Jewish population began to decline more precipitously by the 1990s, as Texarkana attracted few new Jewish residents and mortality and out-migration continued to take their toll. Mount Sinai’s membership fell to 35 individuals in 2011, and the synagogue closed its doors permanently in 2015. Following the closure of Mount Sinai, some of Texarkana’s few remaining Jewish residents traveled to B’nai Zion Congregation in Shreveport for holiday services.

The Jewish population began to decline more precipitously by the 1990s, as Texarkana attracted few new Jewish residents and mortality and out-migration continued to take their toll. Mount Sinai’s membership fell to 35 individuals in 2011, and the synagogue closed its doors permanently in 2015. Following the closure of Mount Sinai, some of Texarkana’s few remaining Jewish residents traveled to B’nai Zion Congregation in Shreveport for holiday services.

Updated March 2024.