Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Eudora, Arkansas

Historical Overview

Eudora, a small town in Chicot County just miles from both the Mississippi and Louisiana borders, was incorporated in 1904 with the onset of railroad development in southeast Arkansas. Named after the plantation which once occupied its land, Eudora’s economy revolved around local agriculture and the transportation of cotton and other crops from surrounding fertile farmlands to larger cities like Memphis. This town’s ideal location spurred commercial growth during the early decades of the 20th century. Following this period of rapid growth, Eudora’s economy slowed, and in the second half of the 20th century the town faced a period of decline which continues into the 21st century.

The rise and fall of Eudora’s Jewish community mirrored the fortunes of the town in general. Some Jews came to the area in the mid-nineteenth century, but most settled in Eudora proper around the turn of the century. Not long after, local Jews of Eudora established Congregation Bene Israel (the Children of Israel), which continued to be a center for cultural and religious life through the late 1930s. In the second half of the 20th century, Eudora’s Jewish population dwindled, and only one Jewish couple remained in the town by the 1990s. As of the early 21st century, there is no Jewish community in Eudora.

Early Jewish Settlers and the Local Jewish Community

In the 19th century Chicot County, home to what would become Eudora, held some of the most productive agricultural land in the state. Prior to emancipation, enslaved Black workers planted and harvested an abundance of cotton, which planters and cotton traders shipped downriver through local ports. The cotton industry’s success in Chicot County drew Jews, most of whom were peddlers, to the area starting in the early 1840s. By 1860 at least 20 Jewish men peddled their wares nearby.

Adolph Meyer (1845-1928), a Jewish immigrant from the German states, established one of the county's most active ports, Cariola Landing. After peddling goods in Louisiana, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Arkansas, he eventually saved enough money to open a mercantile store with his nephew Isaac Dreyfus at the eventual site of Grand Lake. Meyer and Dreyfus built a substantial business, and Meyer once owned some 30 thousand acres of Chicot County farmland in addition to holdings in Missouri. In collaboration with the non-Jewish planter Peter Ford, he established a shipping port on the Mississippi River near his store. The port's name, Cariola Landing, is a portmanteau of the Meyer and Ford's wives' respective names—Carrie and Eola. Meyer’s partnership with a non-Jewish planter demonstrates the ease with which some Jewish immigrants acculturated to southeast Arkansas and other southern locales.

Prior to the Meyer family’s relocation to Eudora, at least one other Jewish family had already settled within town limits. After arriving in 1866, German-Jewish brothers Herman and Ferdinand Weiss set up a mercantile business by the name of H. Weiss and Co. on Eudora’s ridge. They joined a handful of white settlers who began living in Eudora starting in the 1840s. From then until the 1890s the town’s population grew slowly, and by 1895, just four white families and a few Black families lived in Eudora.

Adolph Meyer (1845-1928), a Jewish immigrant from the German states, established one of the county's most active ports, Cariola Landing. After peddling goods in Louisiana, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Arkansas, he eventually saved enough money to open a mercantile store with his nephew Isaac Dreyfus at the eventual site of Grand Lake. Meyer and Dreyfus built a substantial business, and Meyer once owned some 30 thousand acres of Chicot County farmland in addition to holdings in Missouri. In collaboration with the non-Jewish planter Peter Ford, he established a shipping port on the Mississippi River near his store. The port's name, Cariola Landing, is a portmanteau of the Meyer and Ford's wives' respective names—Carrie and Eola. Meyer’s partnership with a non-Jewish planter demonstrates the ease with which some Jewish immigrants acculturated to southeast Arkansas and other southern locales.

Prior to the Meyer family’s relocation to Eudora, at least one other Jewish family had already settled within town limits. After arriving in 1866, German-Jewish brothers Herman and Ferdinand Weiss set up a mercantile business by the name of H. Weiss and Co. on Eudora’s ridge. They joined a handful of white settlers who began living in Eudora starting in the 1840s. From then until the 1890s the town’s population grew slowly, and by 1895, just four white families and a few Black families lived in Eudora.

Additional Jewish families joined earlier arrivals like the Meyer and Weiss families as Eudora became more established as a rail town. In 1901 the Iron Mountain Railway began a line connecting Memphis, Tennessee; Helena, Arkansas; and parts of Louisiana. By 1902, tracks had been completed in Eudora. Soon after, Eudora overtook Grand Lake as the local business hub. Between 1900 and 1920, schools (primary and secondary) and banks opened, and telephone, electric, water and sewage systems were installed. Both economic development and infrastructure improvements attracted new Jewish families to Eudora. There were seventeen Jewish families in Eudora by 1911, consisting of twenty-five adults and numerous children. This nascent community included a mix of German Jews who had migrated south from Saint Louis and Eastern European Jews who had immigrated to the United States after the turn of the century.

German Jew Jacob Rexinger, along with his wife, Theresia, moved to Eudora in 1904 to work in a store run by Adolph Feibelman. Theresia, once there was a substantial Jewish population, encouraged the community to establish an official congregation. In 1911 local Jews formed Congregation Bene Israel. Jacob Rexinger, who was well-versed in Jewish law, served as the lay leader of the congregation. Michael Cahn served as the Congregation’s first president, Morris Schwartz as its first vice president, and Sol Meyer as its first secretary. Although the congregation adopted Reform practices and used Reform prayerbooks published by the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (the Reform movement's governing body), it never became a member of the organization. Bene Israel served not just the Jews of Eudora, but Jews in the surrounding areas in southeast Arkansas and northeast Louisiana. Over the course of its existence, the congregation hosted services at a number of different locations. Originally, congregants worshiped at the Masonic Hall for Friday and High Holiday services, but eventually services moved to the Rex Hotel (the Rexinger family hotel) full time. Bene Israel had a religious school where Maurice Cohen, known as a “marvelous Hebrew educator,” taught for several years. The Congregation continued to meet for just over two decades, disbanding in the late 1930s.

German Jew Jacob Rexinger, along with his wife, Theresia, moved to Eudora in 1904 to work in a store run by Adolph Feibelman. Theresia, once there was a substantial Jewish population, encouraged the community to establish an official congregation. In 1911 local Jews formed Congregation Bene Israel. Jacob Rexinger, who was well-versed in Jewish law, served as the lay leader of the congregation. Michael Cahn served as the Congregation’s first president, Morris Schwartz as its first vice president, and Sol Meyer as its first secretary. Although the congregation adopted Reform practices and used Reform prayerbooks published by the Union of American Hebrew Congregations (the Reform movement's governing body), it never became a member of the organization. Bene Israel served not just the Jews of Eudora, but Jews in the surrounding areas in southeast Arkansas and northeast Louisiana. Over the course of its existence, the congregation hosted services at a number of different locations. Originally, congregants worshiped at the Masonic Hall for Friday and High Holiday services, but eventually services moved to the Rex Hotel (the Rexinger family hotel) full time. Bene Israel had a religious school where Maurice Cohen, known as a “marvelous Hebrew educator,” taught for several years. The Congregation continued to meet for just over two decades, disbanding in the late 1930s.

Business and Civic Life

Jews in Eudora played a significant role in supporting the local rail boom. Many opened dry goods and mercantile stores in town, and a smaller portion made their living in agriculture. At one point, Eudora’s downtown boasted more than half a dozen stores run by Eastern European Jews in addition to several more owned by German Jews. Jews were also involved in other local financial institutions. For instance, Jewish merchants including Alvin Meyer Sr., Morris Schwartz, and Abe Feibelman held senior positions at both the First National Bank of Eudora and the Merchant and Planters Bank.

As a regional rail hub, Eudora was home to a relatively diverse population; Black, Chinese, and Mexican people lived in town. Local Jews, as part of a historically oppressed group too, often empathized with racial minorities (and their maltreatment). For instance, Harold Hart recalled the relationship between Black and Jewish people in Eudora: “Both of us in the minority. Both of us traditionally second class citizens. Whether we liked it or not, it’s the truth.” However, unlike their non-white counterparts, Euro-American Jews were well integrated into white society. Jewish men and women were elected to local and civic leadership positions. Examples of Jewish participation in civic life include Ernestine Friedlander, who served as Eudora’s postmaster in the 1890s, and Carroll Meyer Sr., who served on the Eudora City Council for eighteen years.

Jewish integration into Eudora’s white protestant society also reflected their privileged status in a system of white supremacy. Harold Hart shared stories of his acceptance among his highschool classmates, noting that his popularity got him an invitation to a Ku Klux Klan meeting. When asked if his Jewishness was a problem for local Klan leadership, he explained, “I’m one of the members of the community. I was invited to attend the meeting.” He added that his father, Max Hart, had also been asked to attend Klan meetings.

As a regional rail hub, Eudora was home to a relatively diverse population; Black, Chinese, and Mexican people lived in town. Local Jews, as part of a historically oppressed group too, often empathized with racial minorities (and their maltreatment). For instance, Harold Hart recalled the relationship between Black and Jewish people in Eudora: “Both of us in the minority. Both of us traditionally second class citizens. Whether we liked it or not, it’s the truth.” However, unlike their non-white counterparts, Euro-American Jews were well integrated into white society. Jewish men and women were elected to local and civic leadership positions. Examples of Jewish participation in civic life include Ernestine Friedlander, who served as Eudora’s postmaster in the 1890s, and Carroll Meyer Sr., who served on the Eudora City Council for eighteen years.

Jewish integration into Eudora’s white protestant society also reflected their privileged status in a system of white supremacy. Harold Hart shared stories of his acceptance among his highschool classmates, noting that his popularity got him an invitation to a Ku Klux Klan meeting. When asked if his Jewishness was a problem for local Klan leadership, he explained, “I’m one of the members of the community. I was invited to attend the meeting.” He added that his father, Max Hart, had also been asked to attend Klan meetings.

The Jewish Community in Eudora Today

The Jewish community grew and declined fairly rapidly as its members moved elsewhere to seek new opportunities. In the mid-1930s, there were 36 Jews living in Eudora, but within a few years the congregation dwindled and eventually disbanded. Remaining Jews later worshiped at nearby synagogues in towns such as Pine Bluff, McGhee, and Greenville, Mississippi. In spite of the lack of Jewish institutions, Eudora’s Jews managed to maintain Jewish identity, community, and culture. In many cases, Eudora’s Jewish women played a central role in these efforts—some of which were public and others were more private. Elaine Cornblatt, one of the last Jewish graduates from Eudora’s high school, organized for Rabbi Samuel Rabinowitz of Hebrew Union Congregation in Greenville to speak at her graduation in 1946. Harold Hart also shared anecdotes about Fannie Meyer and Ella Cornblatt of Eudora as well as a “Ms. Swarts” of Greenville organizing and performing his father’s funeral rites.

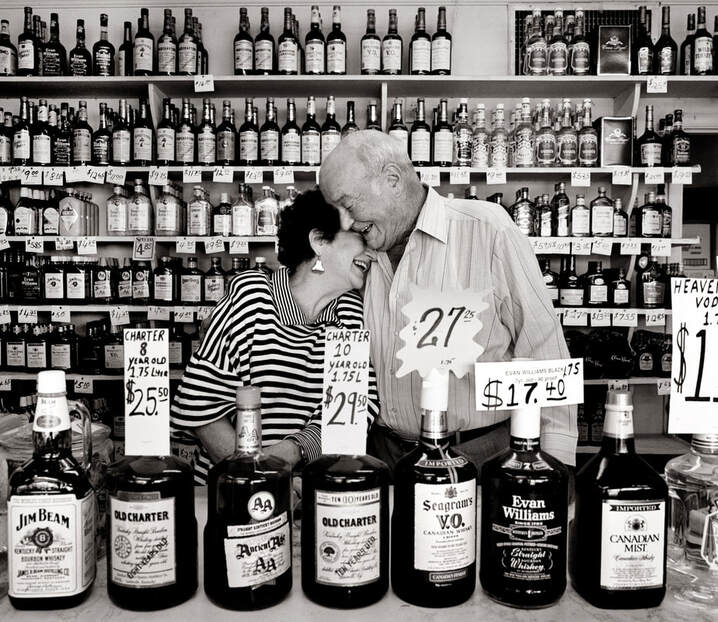

Eudora was still home to several Jewish families in the 1980s, but Jewish-owned stores had all but disappeared by that time. As of 1991 Harold Hart’s Dixie Liquor was the only Jewish-owned store left in town, and he and his wife, Lucille, were the only remaining Jews. Although Eudora’s Jews have since left, visitors can see traces of the town’s Jewish legacy in historical markers, including at Cariola Landing, the site of Adolph Meyer’s shipping port at Grand Lake.

Last updated October 2023.