Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Wynne, Arkansas

Wynne: Historical Overview

Wynne, Arkansas, may be the only American town to have literally fallen off of a train. In the early 1880s the St. Louis, Iron Mountain, and Southern Railroad laid tracks through northeastern Arkansas, crossing from Crowley’s Ridge into the flat, fertile Arkansas Delta. Soon after completion in 1882, one of their trains derailed and left behind an upended boxcar along the west slope of the ridge. Local settlers righted the boxcar and named the site “Wynne Station” after local Civil War hero Captain Jesse Wynne. Wynne Station served as a headquarters for nearby railroad construction projects, and the small settlement soon filled with railway workers, grocery stores, and saloons.

The town’s fortunes grew along with the railroads, and Wynne emerged as the largest settlement in the area by the early 20th century. Upon the completion of an east-west track in 1888, residents changed the name to “Wynne Junction,” then simplified the name and incorporated as “Wynne” later the same year. Some new residents arrived from Wittsburg, an adjacent river port rendered obsolete by more reliable rail transport. In 1903 Wynne’s accessibility and rising population earned it the title of county seat, marking its status and fueling additional growth. Some of the earliest Jewish arrivals to Arkansas settled in the area around Wynne, and the local Jewish community supported its own Jewish institutions in the early 20th century.

The town’s fortunes grew along with the railroads, and Wynne emerged as the largest settlement in the area by the early 20th century. Upon the completion of an east-west track in 1888, residents changed the name to “Wynne Junction,” then simplified the name and incorporated as “Wynne” later the same year. Some new residents arrived from Wittsburg, an adjacent river port rendered obsolete by more reliable rail transport. In 1903 Wynne’s accessibility and rising population earned it the title of county seat, marking its status and fueling additional growth. Some of the earliest Jewish arrivals to Arkansas settled in the area around Wynne, and the local Jewish community supported its own Jewish institutions in the early 20th century.

Early Jewish Settlers

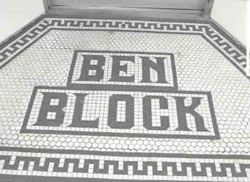

In the 1850s merchant David Block settled in Cold Water Spring, a town on Crowley’s Ridge just north of present-day Wynne. Block opened a general store and soon entered a partnership with Maurice Block, a German immigrant and merchant. While their shared surname may have inspired some feeling of kinship between the two, they were unrelated. The Block partners prospered, supplying agricultural products from the delta regions across the ridge to Memphis and other towns to the east. David Block retired in 1859 while Maurice undertook a variety of successful ventures during the Civil War. He and his wife hid cotton from Confederate troops—which they then sold for large profits—and smuggled cotton and cattle into Memphis. Provisions grew so scarce in the war-racked region that Block received high prices, selling coffee for a dollar a pound and barrels of salt for a hundred dollars.

After the war, Maurice Block moved to Wittsburg, where he and partners opened a large store, D. Block and Company. Following the decline of the river trade, Maurice Block and his family joined in the town’s relocation to Wynne. His son, Isaac, established a sawmill and cotton gin and invested in hundreds of acres of agricultural land. In 1891, Isaac helped establish the Cross County Bank, and served as its first president. Two of the other Block children established themselves in local politics; William served as deputy county clerk, deputy collector of taxes and as a justice of the peace. Another son, J.D., was elected as a state representative in 1886.

Another early Jewish settler, Shields Daltroff, relocated from Wittsburg to help build the new town of Wynne. He clerked at D. Block and Company and ultimately bought out the firm, renaming it Daltroff, Sparks, and Oliver. He moved the store to Wynne where he later served as a justice of the peace.

After the war, Maurice Block moved to Wittsburg, where he and partners opened a large store, D. Block and Company. Following the decline of the river trade, Maurice Block and his family joined in the town’s relocation to Wynne. His son, Isaac, established a sawmill and cotton gin and invested in hundreds of acres of agricultural land. In 1891, Isaac helped establish the Cross County Bank, and served as its first president. Two of the other Block children established themselves in local politics; William served as deputy county clerk, deputy collector of taxes and as a justice of the peace. Another son, J.D., was elected as a state representative in 1886.

Another early Jewish settler, Shields Daltroff, relocated from Wittsburg to help build the new town of Wynne. He clerked at D. Block and Company and ultimately bought out the firm, renaming it Daltroff, Sparks, and Oliver. He moved the store to Wynne where he later served as a justice of the peace.

The establishment of the town of Wynne coincided with a rise in Jewish migration from Eastern Europe. As a result, many new immigrants saw opportunities to “get in on the ground floor” in a growing town. Mike Drexler, an immigrant from Latvia, lived in Kentucky and Missouri before arriving in Wynne around 1905. He established a general merchandise store, and through the next three decades built his business into one of the largest on Crowley’s Ridge. In 1910, Hyman Steinberg traveled from Poland to Little Rock, where he ran a bakery offering challah bread and other traditional foods. Steinberg relocated to Wynne in 1920 where he immersed himself in a variety of business and civic ventures. Steinberg worked closely with farmers to provide equipment and market their crops. He helped found the Merchants and Farmers Gin Company, directed the Cross County Bank and financed a variety of local business ventures. Jews faced little overt prejudice in Wynne. Indeed, the Drexlers, the Steinbergs, and other Jewish families were all active members of the local country club.

Jewish Life in Wynne

The Jewish population grew as more arrivals settled in the area. By 1927, an estimated 60 Jews lived in Wynne. In 1915, Jewish residents established an Orthodox congregation named Ahavah Achim. Religiously devout and well versed in Jewish law, Drexler led the congregation and hosted services on the second floor of his store for approximately thirty families. Despite their relatively small numbers, Jewish residents of Wynne maintained an active communal life. A B’nai B’rith lodge, established in 1914, hosted picnics and events which attracted participants from around the region. Congregation Ahavah Achim continued to meet until the 1940s, when improving road conditions made traveling to services in Memphis easier.

Steinberg's, courtesy of the Cross County Historical Society.

Steinberg's, courtesy of the Cross County Historical Society.

The World War II era marked Wynne’s final days as a major railroad depot. At the height of activity, an estimated 12 troop trains passed through the town every 30 minutes. Residents provided food and provisions for the soldiers and collected their correspondence to be mailed.

During the war, Wynne and much of the region suffered from a worker shortage. In 1944, local citizens agreed to accept German prisoners of war to help alleviate the crisis. A makeshift camp eventually housed as many as 2,000 prisoners who contributed significantly to agricultural production and the infrastructure development in the region. Bette Green, an author of children’s books and a granddaughter of Hyman Steinberg, drew from her memories of the German prisoners to write her popular 1973 novel Summer of My German Soldier.

Some of the many troop trains passing through Wynne carried the town’s Jewish residents off to service, and others brought them home again once the fighting ended. The war led to a boom in Wynne’s economic fortunes as well as its Jewish community. In 1948, 132 Jews lived in town. David Drexler, Mike’s son, returned from the war to manage his restaurant, David’s. He ultimately sold the restaurant and founded the Wynne Insurance and Loan Company, Inc. He also served as president of the Wynne Federal Savings and Loan Company, directed the Cross County Bank, was a member of the Chamber of Commerce, and a chairman of the Wynne Planning Commission. Another Jewish World War II veteran, Benjamin Meyer, returned to Wynne to continue working on his cattle farm.

During the war, Wynne and much of the region suffered from a worker shortage. In 1944, local citizens agreed to accept German prisoners of war to help alleviate the crisis. A makeshift camp eventually housed as many as 2,000 prisoners who contributed significantly to agricultural production and the infrastructure development in the region. Bette Green, an author of children’s books and a granddaughter of Hyman Steinberg, drew from her memories of the German prisoners to write her popular 1973 novel Summer of My German Soldier.

Some of the many troop trains passing through Wynne carried the town’s Jewish residents off to service, and others brought them home again once the fighting ended. The war led to a boom in Wynne’s economic fortunes as well as its Jewish community. In 1948, 132 Jews lived in town. David Drexler, Mike’s son, returned from the war to manage his restaurant, David’s. He ultimately sold the restaurant and founded the Wynne Insurance and Loan Company, Inc. He also served as president of the Wynne Federal Savings and Loan Company, directed the Cross County Bank, was a member of the Chamber of Commerce, and a chairman of the Wynne Planning Commission. Another Jewish World War II veteran, Benjamin Meyer, returned to Wynne to continue working on his cattle farm.

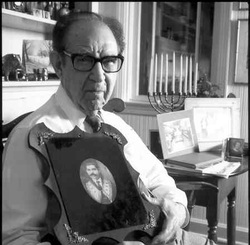

David Reagler, c. 1970s. Courtesy of the Reagler family.

David Reagler, c. 1970s. Courtesy of the Reagler family.

Hyman Steinberg’s three sons, Isadore, Morris, and Jacob all remained in Wynne and played an active role in the Jewish community and Wynne public life. Isadore, or “Izzy” as he was more commonly known, headed the Merchants and Farmers’ Cotton Gin founded by his father and served as a member of the Chamber of Commerce. All three brothers remained religious after the decline of the Ahavah Achim congregation, and they regularly traveled to Memphis and Little Rock to attend services. Upon Hyman’s passing in 1958, family members donated property to the city of Wynne for the establishment of the Hyman Steinberg Park.

Another significant Wynne Jewish family were the Reaglers, who arrived in Wynne by 1920. David Reagler, a local native, left his grandfather's dime store in the mid-1960s to found Handy Dollar Store with his wife Joanne (born in New Iberia, Lousiana). In addition to Joane’s work in the family business, she held a master's degree in psychiatric social work and earned accolades as a community activist over the course of more than four decades in Wynne. Joane and David operated Handy Dollar Store until 1998 and relocated to Hot Springs in 2006.

Another significant Wynne Jewish family were the Reaglers, who arrived in Wynne by 1920. David Reagler, a local native, left his grandfather's dime store in the mid-1960s to found Handy Dollar Store with his wife Joanne (born in New Iberia, Lousiana). In addition to Joane’s work in the family business, she held a master's degree in psychiatric social work and earned accolades as a community activist over the course of more than four decades in Wynne. Joane and David operated Handy Dollar Store until 1998 and relocated to Hot Springs in 2006.

The Decline of Wynne’s Jewish Community

Wynne grew to prominence through the growth of the railroads and the decline of river transport, but fortunately the town did not follow Wittsburg’s fate once the railroads themselves became obsolete. The last passenger train passed through Wynne in 1965, but by this point the town possessed a more diverse economy which persists into the 21st century. A number of major manufacturers operate in the area, as well as plants processing a variety of agricultural products. Village Creek State Park, one of the largest in Arkansas, brings visitors from around the country and the world to Wynne and scenic Crowley’s Ridge. Despite this overall economic growth, Wynne’s Jewish community declined in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Although Wynne does not support an organized Jewish community in the 21st century, many of its former Jewish residents participate in congregations elsewhere in Arkansas and neighboring states.

Although Wynne does not support an organized Jewish community in the 21st century, many of its former Jewish residents participate in congregations elsewhere in Arkansas and neighboring states.