Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Albany, Georgia

Albany: Historical Overview

|

Located along the Flint River in southwest Georgia, Albany was first settled by Connecticut businessman Nelson Tift in 1836, who named the future city after the capital of New York. Due to its location at the head of a navigable river and amidst fertile cotton growing land, Albany soon emerged as a regional commercial center. A handful of Jewish immigrants were soon attracted to the bustling seat of Doughtery County in the 1840s, the seeds of Jewish community that last to this day.

|

Stories of the Jewish Community in Albany

Marx Smith's home,where Albany Jews first met to pray together.

Marx Smith's home,where Albany Jews first met to pray together.

Early Settlers

Marx Smith was among the first, along with Jacob Gross and Julius Breitenbach, all of whom were immigrants from Bavaria. Smith, a general merchant, was the most successful of the three; by 1860, his net worth was $12,000. Gross owned a grocery store. Julius Breitenbach died during the 1860s, and his wife Sophia, who was also a Bavarian immigrant, became a hotel keeper to support the family. These three families formed the nucleus of Albany’s Jewish community.

B'nai Israel and its Congregants

Marx Smith's home,where Albany Jews first met to pray together. In 1854, four Jews, including Marx Smith and Jacob Gross, incorporated the United Hebrew Society of Albany, which was founded to purchase land for a cemetery and build a house of worship. In 1858, they purchased land for a cemetery. Despite this early growth, Albany Jews did not officially form congregation B’nai Israel until 1876, when an estimated 100 Jews lived in the city. Sam Mayer was elected president of the fledgling congregation, which quickly became a charter member of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations. B’nai Israel was a Reform congregation from its founding.

A list of the 41 founders of the congregation offers a clear portrait of this small Southern Jewish community. Most were young immigrants; their average age was 31 at the time of the founding. Ninety percent were foreign-born, with two-thirds from Germany and 22% from the Austro-Hungarian empire. Most were involved in commercial trade: over 60% were merchants, while another 20% were store clerks or bookkeepers.

During its early years, B’nai Israel met in the Mayer Building and later in the Welch Building in downtown Albany. In 1882, the congregation built a small synagogue on the corner of Jefferson and Broad Streets. Fourteen years later, members built a new larger temple on the corner of Jefferson and Oglethorpe. Many of the members of the congregation built houses in the area around the synagogue in the early 20th century. Despite its small size, the congregation was first able to hire a rabbi in 1885. While B’nai Israel’s first three rabbis only stayed for a year each, in 1889, they brought in F.W. Jesselson to lead the congregation, who ended up staying for nine years. In 1898, they hired a 22-year-old graduate of the Hebrew Union College, Edmund A. Landau, who would spend the next 47 years leading B’nai Israel. He married a local girl, Rosa Geiger, who had been in his first confirmation class.

Marx Smith was among the first, along with Jacob Gross and Julius Breitenbach, all of whom were immigrants from Bavaria. Smith, a general merchant, was the most successful of the three; by 1860, his net worth was $12,000. Gross owned a grocery store. Julius Breitenbach died during the 1860s, and his wife Sophia, who was also a Bavarian immigrant, became a hotel keeper to support the family. These three families formed the nucleus of Albany’s Jewish community.

B'nai Israel and its Congregants

Marx Smith's home,where Albany Jews first met to pray together. In 1854, four Jews, including Marx Smith and Jacob Gross, incorporated the United Hebrew Society of Albany, which was founded to purchase land for a cemetery and build a house of worship. In 1858, they purchased land for a cemetery. Despite this early growth, Albany Jews did not officially form congregation B’nai Israel until 1876, when an estimated 100 Jews lived in the city. Sam Mayer was elected president of the fledgling congregation, which quickly became a charter member of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations. B’nai Israel was a Reform congregation from its founding.

A list of the 41 founders of the congregation offers a clear portrait of this small Southern Jewish community. Most were young immigrants; their average age was 31 at the time of the founding. Ninety percent were foreign-born, with two-thirds from Germany and 22% from the Austro-Hungarian empire. Most were involved in commercial trade: over 60% were merchants, while another 20% were store clerks or bookkeepers.

During its early years, B’nai Israel met in the Mayer Building and later in the Welch Building in downtown Albany. In 1882, the congregation built a small synagogue on the corner of Jefferson and Broad Streets. Fourteen years later, members built a new larger temple on the corner of Jefferson and Oglethorpe. Many of the members of the congregation built houses in the area around the synagogue in the early 20th century. Despite its small size, the congregation was first able to hire a rabbi in 1885. While B’nai Israel’s first three rabbis only stayed for a year each, in 1889, they brought in F.W. Jesselson to lead the congregation, who ended up staying for nine years. In 1898, they hired a 22-year-old graduate of the Hebrew Union College, Edmund A. Landau, who would spend the next 47 years leading B’nai Israel. He married a local girl, Rosa Geiger, who had been in his first confirmation class.

Charles Wessolowsky

Charles Wessolowsky

The Wessolowsky Family

One of these founders was Charles Wessolowsky, who came to Albany from Savannah with his wife Johanna and their three children in 1869 and opened a grocery store. The Prussian-born Wesselowsky was a very gregarious and popular fellow and soon won election to the town’s board of alderman in 1870. In 1875, he was elected to the first of three terms in the state legislature. Wessolowsky also became a leader of the local Jewish community. He convinced other local Jews to form a Hebrew Benevolent Society to help those in need and founded the congregation’s religious school with his wife Johanna. Wessolowsky was active in both the Masons and the B’nai B’rith, which had been established in Albany in 1873.

Wessolowsky was more successful in politics than in business, and thus happily left the retail trade behind when he agreed to become the associate editor of the Jewish South newspaper in 1877. The paper had been founded by Rabbi E.B.M. Browne of Atlanta. Wessolowsky spent four years with the newspaper and often traveled across the South selling subscriptions to the Jewish South and organizing local chapters of B’nai B’rith. His letters to Rabbi Browne about the communities he visited were published in 1982 in the book Reflections of Southern Jewry.

One of these founders was Charles Wessolowsky, who came to Albany from Savannah with his wife Johanna and their three children in 1869 and opened a grocery store. The Prussian-born Wesselowsky was a very gregarious and popular fellow and soon won election to the town’s board of alderman in 1870. In 1875, he was elected to the first of three terms in the state legislature. Wessolowsky also became a leader of the local Jewish community. He convinced other local Jews to form a Hebrew Benevolent Society to help those in need and founded the congregation’s religious school with his wife Johanna. Wessolowsky was active in both the Masons and the B’nai B’rith, which had been established in Albany in 1873.

Wessolowsky was more successful in politics than in business, and thus happily left the retail trade behind when he agreed to become the associate editor of the Jewish South newspaper in 1877. The paper had been founded by Rabbi E.B.M. Browne of Atlanta. Wessolowsky spent four years with the newspaper and often traveled across the South selling subscriptions to the Jewish South and organizing local chapters of B’nai B’rith. His letters to Rabbi Browne about the communities he visited were published in 1982 in the book Reflections of Southern Jewry.

Samuel B. Brown

Samuel B. Brown

Jewish Civic Engagement

As early as 1871, the editor of Albany’s local newspaper noted that “no people on earth are more liberal in benevolent projects or social enterprises” than Albany Jews. Two of the most important of these civic leaders were Samuel B. Brown and Joseph Ehrlich. Samuel B. Brown was born in Atlanta in 1855 to German-Jewish parents. His family moved to Albany in 1869. As a young man, he worked as a store clerk before becoming a partner in his own firm Greenfield and Brown. He later owned a high-end men’s clothing store. According to a history of Dougherty County, Brown’s “rise in the business world was without interruption, and he finally became the leading business man of Albany.” Brown was a big local booster, helping to finance many local enterprises. Brown founded several businesses in Albany, including the Planters Oil Company, the Flint River Brick Company, the Exchange Bank, and the Albany National Bank. Brown was the longtime president of both of these banks. Brown was elected mayor in 1901 and 1902 and also served several terms on the board of aldermen. When he died in 1922, the local newspaper reported that “a wave of sorrow swept over the splendid city he had helped to build.” Brown left $5000 of his estate to the local hospital, upon whose board he had served as chairman.

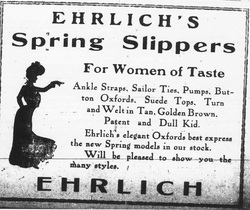

Joseph Ehrlich came to the United States from Prague in 1868. After spending some years in Connecticut, Ehrlich moved to Albany in 1875, where he opened a clothing store and tailoring business. In 1881, Ehrlich opened a shoe and hat store, which became a big success. Ehrlich was first elected to the Albany Board of Aldermen in 1888; he went on to serve as an alderman for 33 years. Ehrlich was also a longtime member of the local board of education and secretary of the local Masonic Lodge for 21 years. Both Ehrlich and Samuel Brown were also leaders of the local Jewish community. Brown served as Beth Israel’s president from 1894 until his death in 1922, whereupon Ehrlich took over the office for the next 16 years.

Perhaps because of the prominence of men like Brown and Ehrlich, Jews enjoyed tremendous acceptance in Albany. Jews were welcomed into the local country club; Brown served as its longtime president. Bertha Brown and Lily Hofmayer both served as president of the Albany Women’s Club, in which many other Jewish women were active. Several other Albany Jews served on the board of aldermen, including E.H. Kalmon and Morris Wessolowsky, Charles’ son. Jews were also actively involved in education in Albany. Henrietta Sterne, the daughter of Marx and Caroline Smith, founded a private school in 1877. She ran the school, known as the A. Sterne Institute, until she left Albany for Anniston, Alabama, in 1888. The school continued under the leadership of her sister-in-law Pauline Sterne until it closed in 1917.

Generally, it was the women who took the lead in the Albany Jewish community’s charitable efforts. In 1878, a group of 13 Jewish women founded the Hebrew Ladies Benevolent Society. Its goal was to help those in need, regardless of religion. The group furnished rooms at the local hospital and provided free lunches to poor school children. They also donated money to several local charities. For over a century, the Hebrew Ladies Benevolent Society was the charitable arm of the Albany Jewish community. The group is still active today, and remains the oldest Jewish women’s organization in Georgia. All of the society’s founders were members of B’nai Israel, and over the years there has been a great deal of overlap between the society and the congregation. In 1895, Albany women founded the Ladies’ Aid Society, which worked to support the congregation and synagogue. In 1917 it changed its name to the Temple Sisterhood. The two women’s organizations existed together for over a century, with the Benovolent Society focused on helping those outside of the congregation, while the Sisterhood supported the work of B’nai Israel. In 2006, the two organizations, which largely had the same membership, finally merged.

As early as 1871, the editor of Albany’s local newspaper noted that “no people on earth are more liberal in benevolent projects or social enterprises” than Albany Jews. Two of the most important of these civic leaders were Samuel B. Brown and Joseph Ehrlich. Samuel B. Brown was born in Atlanta in 1855 to German-Jewish parents. His family moved to Albany in 1869. As a young man, he worked as a store clerk before becoming a partner in his own firm Greenfield and Brown. He later owned a high-end men’s clothing store. According to a history of Dougherty County, Brown’s “rise in the business world was without interruption, and he finally became the leading business man of Albany.” Brown was a big local booster, helping to finance many local enterprises. Brown founded several businesses in Albany, including the Planters Oil Company, the Flint River Brick Company, the Exchange Bank, and the Albany National Bank. Brown was the longtime president of both of these banks. Brown was elected mayor in 1901 and 1902 and also served several terms on the board of aldermen. When he died in 1922, the local newspaper reported that “a wave of sorrow swept over the splendid city he had helped to build.” Brown left $5000 of his estate to the local hospital, upon whose board he had served as chairman.

Joseph Ehrlich came to the United States from Prague in 1868. After spending some years in Connecticut, Ehrlich moved to Albany in 1875, where he opened a clothing store and tailoring business. In 1881, Ehrlich opened a shoe and hat store, which became a big success. Ehrlich was first elected to the Albany Board of Aldermen in 1888; he went on to serve as an alderman for 33 years. Ehrlich was also a longtime member of the local board of education and secretary of the local Masonic Lodge for 21 years. Both Ehrlich and Samuel Brown were also leaders of the local Jewish community. Brown served as Beth Israel’s president from 1894 until his death in 1922, whereupon Ehrlich took over the office for the next 16 years.

Perhaps because of the prominence of men like Brown and Ehrlich, Jews enjoyed tremendous acceptance in Albany. Jews were welcomed into the local country club; Brown served as its longtime president. Bertha Brown and Lily Hofmayer both served as president of the Albany Women’s Club, in which many other Jewish women were active. Several other Albany Jews served on the board of aldermen, including E.H. Kalmon and Morris Wessolowsky, Charles’ son. Jews were also actively involved in education in Albany. Henrietta Sterne, the daughter of Marx and Caroline Smith, founded a private school in 1877. She ran the school, known as the A. Sterne Institute, until she left Albany for Anniston, Alabama, in 1888. The school continued under the leadership of her sister-in-law Pauline Sterne until it closed in 1917.

Generally, it was the women who took the lead in the Albany Jewish community’s charitable efforts. In 1878, a group of 13 Jewish women founded the Hebrew Ladies Benevolent Society. Its goal was to help those in need, regardless of religion. The group furnished rooms at the local hospital and provided free lunches to poor school children. They also donated money to several local charities. For over a century, the Hebrew Ladies Benevolent Society was the charitable arm of the Albany Jewish community. The group is still active today, and remains the oldest Jewish women’s organization in Georgia. All of the society’s founders were members of B’nai Israel, and over the years there has been a great deal of overlap between the society and the congregation. In 1895, Albany women founded the Ladies’ Aid Society, which worked to support the congregation and synagogue. In 1917 it changed its name to the Temple Sisterhood. The two women’s organizations existed together for over a century, with the Benovolent Society focused on helping those outside of the congregation, while the Sisterhood supported the work of B’nai Israel. In 2006, the two organizations, which largely had the same membership, finally merged.

Albany Jews During WWI

Rabbi Landau and other Albany Jews got heavily involved in local efforts during the first world war. Landau and I.J. Hofmayer were “four-minute speakers” who worked to sell war bonds. Samuel Brown was chairman of the local Red Cross chapter during the war. Although the Albany Jewish community was small, 37 Jewish men served in the military during the war. After the war, Albany Jews helped to raise money for Jews still suffering in Europe. In 1922, they raised $10,000 for the cause, much of it from local Gentiles. According to Rabbi Landau, “the result of the drive was but fresh evidence of the fine spirit of mutual understanding, sympathy, and esteem that has ever existed in Albany between Jew and Gentile.”

Rabbi Landau and other Albany Jews got heavily involved in local efforts during the first world war. Landau and I.J. Hofmayer were “four-minute speakers” who worked to sell war bonds. Samuel Brown was chairman of the local Red Cross chapter during the war. Although the Albany Jewish community was small, 37 Jewish men served in the military during the war. After the war, Albany Jews helped to raise money for Jews still suffering in Europe. In 1922, they raised $10,000 for the cause, much of it from local Gentiles. According to Rabbi Landau, “the result of the drive was but fresh evidence of the fine spirit of mutual understanding, sympathy, and esteem that has ever existed in Albany between Jew and Gentile.”

B'nai Israel's second synagogue, built in 1896

B'nai Israel's second synagogue, built in 1896

Jewish Merchants of Albany

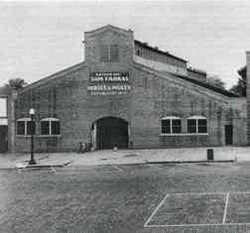

As in other Southern towns, most Albany Jews were involved in retail trade. Already by 1871, there were 22 Jewish-owned stores in Albany. During the late 19th century, Jewish immigrants continued to settle in Albany seeking economic opportunity. Sam Farkas came to Albany from Hungary in 1872. Soon, he established a horse and mule business which also sold farm equipment. He achieved great economic success, and built a barn that could hold 300 mules and horses. Jacob Rosenberg left Roumania in 1889, settling initially in New York City. In 1892, Rosenberg moved to Troy, Alabama, where he opened a store with his brothers Abraham and Isaac. After he met Annie Cohn during a visit to Albany in 1895, Jacob convinced his brothers to let him open a branch store there. After marrying Annie, Jacob Rosenberg ran the Rosenberg Brothers store in Albany for the next 42 years, until he died in 1938. In 1925, Jacob built a new store in downtown Albany, which had three stories and a basement as well as two elevators. The Rosenberg Brothers store became one of the largest and most successful in southwest Georgia. When Jacob died, every store in town closed during his funeral. The business was carried on by Jacob’s son Joseph and later his grandson Ralph Rosenberg. In 1991, the Rosenberg Brothers business finally closed due to increased competition from discount chain stores.

As in other Southern towns, most Albany Jews were involved in retail trade. Already by 1871, there were 22 Jewish-owned stores in Albany. During the late 19th century, Jewish immigrants continued to settle in Albany seeking economic opportunity. Sam Farkas came to Albany from Hungary in 1872. Soon, he established a horse and mule business which also sold farm equipment. He achieved great economic success, and built a barn that could hold 300 mules and horses. Jacob Rosenberg left Roumania in 1889, settling initially in New York City. In 1892, Rosenberg moved to Troy, Alabama, where he opened a store with his brothers Abraham and Isaac. After he met Annie Cohn during a visit to Albany in 1895, Jacob convinced his brothers to let him open a branch store there. After marrying Annie, Jacob Rosenberg ran the Rosenberg Brothers store in Albany for the next 42 years, until he died in 1938. In 1925, Jacob built a new store in downtown Albany, which had three stories and a basement as well as two elevators. The Rosenberg Brothers store became one of the largest and most successful in southwest Georgia. When Jacob died, every store in town closed during his funeral. The business was carried on by Jacob’s son Joseph and later his grandson Ralph Rosenberg. In 1991, the Rosenberg Brothers business finally closed due to increased competition from discount chain stores.

Sam Farkas' mule barn

Sam Farkas' mule barn

Morris Gortatowsky left Prussia and settled in Georgia by 1874. In 1880, he was a rag and hide dealer in Albany. During the next 20 years, Gortatowsky somehow moved from this modest business to become a significant plantation owner. His children also became important figures in the local economy. Harry Gortatowsky owned a cotton warehouse, while his brothers Adolph and Leon managed several theaters across the state, including the grand Albany Theater that had been built on the same site as Sam Farkas’ mule barn in 1927. Adolph later went into the insurance business with Edward Davis and became an important booster of the local economy. Through his lobbying efforts, Gortatowsky helped to bring Turner Air Force Field and a Marine base to the area. He also helped to bring a hosiery mill to Albany in the years before World War II. Leon’s son Maurice founded the Georgia Tire and Battery Company in the early 1950s. When he died in 1999, he left all of his $5 million estate to local charities, including over $1 million to Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College in Tifton.

Isadore Prisant left Russia in 1894 when he was only 16 years old. After spending several years in New York, Prisant settled in Albany, where he opened a dry goods store with his brother Harry who had recently joined him in America. A few years later, their older brother Lewis joined them in Albany. A watchmaker by trade, Lewis Prisant set up his own shop within the Prisant Brother store before he opened his own jewelry store next door. The Prisant Brothers store later closed, though L. Prisant Jewelers remained in business until 1985, when Lewis’ grandson Larry sold the business.

Many of these Jewish-owned businesses were centered around Broad Street in downtown Albany. In 1930, the following businesses were clustered together on just two blocks of Broad Street: Issac Minsk, New York Bargain House, Rosenberg Brothers Department Store, Prisant Brothers Department Store, Louis Prisant Jewelers, and J. Ehrlich Shoes and Hats.

Isadore Prisant left Russia in 1894 when he was only 16 years old. After spending several years in New York, Prisant settled in Albany, where he opened a dry goods store with his brother Harry who had recently joined him in America. A few years later, their older brother Lewis joined them in Albany. A watchmaker by trade, Lewis Prisant set up his own shop within the Prisant Brother store before he opened his own jewelry store next door. The Prisant Brothers store later closed, though L. Prisant Jewelers remained in business until 1985, when Lewis’ grandson Larry sold the business.

Many of these Jewish-owned businesses were centered around Broad Street in downtown Albany. In 1930, the following businesses were clustered together on just two blocks of Broad Street: Issac Minsk, New York Bargain House, Rosenberg Brothers Department Store, Prisant Brothers Department Store, Louis Prisant Jewelers, and J. Ehrlich Shoes and Hats.

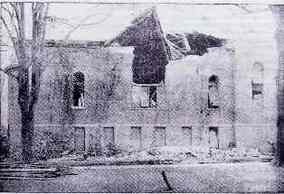

B'nai Israel after the tornado

B'nai Israel after the tornado

The Tornado of 1940

This cluster of Jewish businesses was hard hit by the tornado that devastated Albany on February 10, 1940. The Rosenberg Brothers store had to close for a while after its windows were broken and water damaged much of their merchandise. The store ran a big ad in the Albany Herald vowing to reopen soon and proclaiming “Albany has suffered almost inestimable damage, but the Spirit of Albany is unmarred.” Ten other Jewish owned-business were damaged by the tornado, including the Prisant Brothers Department Store, the Hofmayer Dry Goods Company, the Globe Department Store, Cohen Brothers Store, and the Robinson Drug Company. Since many of these business owners lived close to their stores, many of their homes were damaged as well. In a letter to the editor of the Southern Israelite newspaper, Rabbi Landau declared “there is scarcely a member of the congregation who has not suffered.”

The tornado also did serious damage to B’nai Israel’s synagogue. Part of its north wall was destroyed and the roof was damaged beyond repair. All of its windows were blown out. According to the local newspaper, B’nai Israel suffered more damage than any other house of worship in Albany. The congregation only had $15,000 in insurance and had to largely rebuild their synagogue. After the congregation was displaced by the tornado, several local churches offered their buildings to B’nai Israel as a temporary house of worship. B’nai Israel ended up meeting regularly in the local Masonic Temple while a new synagogue was built on the same site as their old one.

This cluster of Jewish businesses was hard hit by the tornado that devastated Albany on February 10, 1940. The Rosenberg Brothers store had to close for a while after its windows were broken and water damaged much of their merchandise. The store ran a big ad in the Albany Herald vowing to reopen soon and proclaiming “Albany has suffered almost inestimable damage, but the Spirit of Albany is unmarred.” Ten other Jewish owned-business were damaged by the tornado, including the Prisant Brothers Department Store, the Hofmayer Dry Goods Company, the Globe Department Store, Cohen Brothers Store, and the Robinson Drug Company. Since many of these business owners lived close to their stores, many of their homes were damaged as well. In a letter to the editor of the Southern Israelite newspaper, Rabbi Landau declared “there is scarcely a member of the congregation who has not suffered.”

The tornado also did serious damage to B’nai Israel’s synagogue. Part of its north wall was destroyed and the roof was damaged beyond repair. All of its windows were blown out. According to the local newspaper, B’nai Israel suffered more damage than any other house of worship in Albany. The congregation only had $15,000 in insurance and had to largely rebuild their synagogue. After the congregation was displaced by the tornado, several local churches offered their buildings to B’nai Israel as a temporary house of worship. B’nai Israel ended up meeting regularly in the local Masonic Temple while a new synagogue was built on the same site as their old one.

Community Growth

Albany was soon able to rebuild from the tornado with the help of World War II, which brought a lot of activity to the military bases in the area. With this wartime bustle, Albany’s Jewish community continued to grow. Albany’s Jewish population went from 290 Jews in 1937 to 475 in 1960, before peaking at 525 in 1968. B’nai Israel grew as well, from 70 members in 1940 to 150 in 1962. The 1950s and 60s were the peak years for the Albany Jewish community, as their religious school was packed with children.

Late 20th Century Decline

B'nai Israel sold its downtown building to a bank in 1995. Unfortunately, many of the children of the 50s and 60s did not stay in Albany once they grew up. Many left for larger cities like Atlanta, seeking greater economic and social opportunities. By the 1980s, the Jewish-owned stores of Albany were closing due to competition from national chain stores and the owners’ children''s lack of interest in joining the family business. Over the last few decades, Albany’s Jewish population has dropped precipitously. By 1997, only 200 Jews still lived in Albany. B’nai Israel sold their building in 1995 to a bank and built a smaller synagogue on Gillionville Road, which was dedicated in 1999. During the four years in which B’nai Israel had no home, they met at the Covenant Presbyterian Church.

While the Jewish community was shrinking, Albany Jews continued their active involvement in the town’s civic affairs. Abner Israel was a local lawyer who served as a municipal court judge in the 1950s. Joseph Rosenberg was a major economic booster, co-founding the Bank of Albany and helping to bring several industries to town. He also served as president of the Albany Board of Education. Edward Davis was a city commissioner and assistant fire chief. Marvin Lorig, who owned a successful diaper and industrial laundry service, spent 27 years on the city planning board. Harry Goldstein served on the city council in the 1970s and 80s. David Maschke, an architect who designed B’nai Israel’s new synagogue, has spent several years on the Albany School Board and was elected its chairman in 2008.

Albany was soon able to rebuild from the tornado with the help of World War II, which brought a lot of activity to the military bases in the area. With this wartime bustle, Albany’s Jewish community continued to grow. Albany’s Jewish population went from 290 Jews in 1937 to 475 in 1960, before peaking at 525 in 1968. B’nai Israel grew as well, from 70 members in 1940 to 150 in 1962. The 1950s and 60s were the peak years for the Albany Jewish community, as their religious school was packed with children.

Late 20th Century Decline

B'nai Israel sold its downtown building to a bank in 1995. Unfortunately, many of the children of the 50s and 60s did not stay in Albany once they grew up. Many left for larger cities like Atlanta, seeking greater economic and social opportunities. By the 1980s, the Jewish-owned stores of Albany were closing due to competition from national chain stores and the owners’ children''s lack of interest in joining the family business. Over the last few decades, Albany’s Jewish population has dropped precipitously. By 1997, only 200 Jews still lived in Albany. B’nai Israel sold their building in 1995 to a bank and built a smaller synagogue on Gillionville Road, which was dedicated in 1999. During the four years in which B’nai Israel had no home, they met at the Covenant Presbyterian Church.

While the Jewish community was shrinking, Albany Jews continued their active involvement in the town’s civic affairs. Abner Israel was a local lawyer who served as a municipal court judge in the 1950s. Joseph Rosenberg was a major economic booster, co-founding the Bank of Albany and helping to bring several industries to town. He also served as president of the Albany Board of Education. Edward Davis was a city commissioner and assistant fire chief. Marvin Lorig, who owned a successful diaper and industrial laundry service, spent 27 years on the city planning board. Harry Goldstein served on the city council in the 1970s and 80s. David Maschke, an architect who designed B’nai Israel’s new synagogue, has spent several years on the Albany School Board and was elected its chairman in 2008.

The Jewish Community in Albany Today

While the number of Jews in Albany has continued to decline, B’nai Israel has remained active. After Rabbi Landau’s death in 1945, the congregation had a series of rabbis, including Harry Caplan, Martin Hinchin, Joseph Freedman, Charles Lesser, David Zielonka, and William Cohen. In 1987, Rabbi Elijah Palnick came to Albany from Little Rock, serving B’nai Israel for the next 12 years. Today, the congregation has 85 member households, though most are elderly