Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Atlanta, Georgia

Atlanta: Historical Overview

|

For almost 150 years, Atlanta has symbolized a “New South,” where commerce, industry, and economic progress overshadowed the poverty and agricultural economy of much of the rest of the region. As merchants and businessmen with little interest or experience with farming, Jews have always been a good fit in Atlanta. Jews played an important role in Atlanta’s rise and development, helping to build the city and gaining remarkable acceptance. Despite this, Atlanta has also witnessed two of the most infamous incidents of anti-Semitism in American Jewish history, as Jews were targeted by forces who opposed the economic and social changes which Jews had come to symbolize. In recent decades, Atlanta has become a national center of American Jewish life as Jews have flocked to the city from smaller cities across the South and larger cities in the North.

The railroad gave birth to the city of Atlanta, and even named it. Originally founded as Marthasville in 1843, the name was too long to fit on a train ticket, which was essential as the new settlement was established as a terminus of the Georgia Railroad. Renamed Atlanta in 1845, the small town quickly became a railroad center for the southeast, growing from 500 people in 1847 to 9,500 on the eve of the Civil War. With such incredible growth, there were tremendous economic opportunities for enterprising Jewish immigrants. |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Atlanta

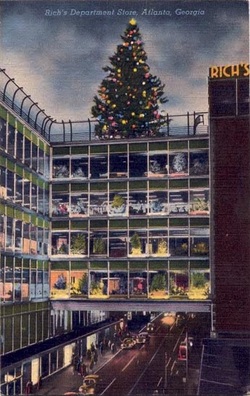

Rich's Department Store

Rich's Department Store

Early Settlers

The first two Jews to settle in Atlanta, Jacob Haas and Henry Levi, arrived in 1845. The two German Jewish immigrants went into business together in a general merchandise store. They didn't stay in Atlanta long; both were gone by 1851. Other early Jewish pioneers in Atlanta included Aaron Alexander, who opened the town’s first drug store, Moses Sternberger, Simon Frankfort, and Adolph Brady. These early settlers were heavily concentrated in retail trade, especially dry goods and clothing; by 1850, Jews owned 10% of Atlanta’s stores, many of which were located on Whitehall Street. During these early years, there was a high degree of population turnover, and most of these Jewish settlers did not stay in Atlanta. Of the 16 Jews who moved to Atlanta prior to 1850, only one couple, David and Eliza Mayer, still lived in the Gate City in 1860. David Mayer had become a very successful dry goods merchant; by 1859, he was worth $59,000 and owned six slaves.

During this early period, there was usually not ten men to make a minyan, so religious services were held only sporadically. In 1852, one of the leading rabbis in America, Isaac Leeser, came to Atlanta and led services at someone’s home. While Rabbi Leeser urged Atlanta’s small Jewish community to found a religious congregation, it was another eight years before Atlanta Jews began to establish Jewish institutions. Most likely, it was the high degree of population turnover that slowed the process of establishing a Jewish congregation in Atlanta. In 1860, Atlanta’s Jews founded the Hebrew Benevolent Society, a burial society which soon acquired six lots in the city cemetery. Not until 1862 did members of the society formally establish the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation, which had 30 founding members with many living in surrounding towns. Initially, the group worshiped in the local Masonic Hall.

The first two Jews to settle in Atlanta, Jacob Haas and Henry Levi, arrived in 1845. The two German Jewish immigrants went into business together in a general merchandise store. They didn't stay in Atlanta long; both were gone by 1851. Other early Jewish pioneers in Atlanta included Aaron Alexander, who opened the town’s first drug store, Moses Sternberger, Simon Frankfort, and Adolph Brady. These early settlers were heavily concentrated in retail trade, especially dry goods and clothing; by 1850, Jews owned 10% of Atlanta’s stores, many of which were located on Whitehall Street. During these early years, there was a high degree of population turnover, and most of these Jewish settlers did not stay in Atlanta. Of the 16 Jews who moved to Atlanta prior to 1850, only one couple, David and Eliza Mayer, still lived in the Gate City in 1860. David Mayer had become a very successful dry goods merchant; by 1859, he was worth $59,000 and owned six slaves.

During this early period, there was usually not ten men to make a minyan, so religious services were held only sporadically. In 1852, one of the leading rabbis in America, Isaac Leeser, came to Atlanta and led services at someone’s home. While Rabbi Leeser urged Atlanta’s small Jewish community to found a religious congregation, it was another eight years before Atlanta Jews began to establish Jewish institutions. Most likely, it was the high degree of population turnover that slowed the process of establishing a Jewish congregation in Atlanta. In 1860, Atlanta’s Jews founded the Hebrew Benevolent Society, a burial society which soon acquired six lots in the city cemetery. Not until 1862 did members of the society formally establish the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation, which had 30 founding members with many living in surrounding towns. Initially, the group worshiped in the local Masonic Hall.

Image courtesy of

The Temple

Image courtesy of

The Temple

The Civil War

The Hebrew Benevolent Congregation benefited from Atlanta’s extraordinary growth during the Civil War. Atlanta’s population more than doubled during the war, reaching 20,000 people as the city became an important war supply manufacturing and storage center. This role made it a target for the Union Army, which burned the city after its capture in 1864. Atlanta Jews were divided by the war. Some, like David Mayer, were strong secessionists who quickly signed up to fight for the Southern cause. Others like Leo Cahn, who worked as a clerk in Mayer’s store, had no allegiance to a land where he had just recently settled and little interest in fighting for it. Cahn left Atlanta soon after mandatory conscription was implemented. The war ended badly for Atlanta, as General Sherman and his men burned two-thirds of the city.

After the Civil War

Despite this economic blow, Atlanta and its Jewish community soon reemerged from the ashes of the city’s destruction as the Gate City became an economic center of the “New South.” It did not take Atlanta long to rebound from the war. In 1865, the city had 150 stores; by 1869 it had 875 stores. While $3 million worth of goods had been sold in Atlanta in 1859, this annual figure had risen to $35 million by 1872. By 1873, there were five different railroad lines in the city. A growing number of Jews settled in Atlanta seeking to take advantage of this remarkable growth. Their presence was hailed by civic boosters. One local newspaper declared in 1875, “nothing is so indicative of a city’s progress as to see an influx of Jews…because they are thrifty and progressive people who never fail to build up a town they settle in.”

Among these newly arriving Jews were the Rich brothers. Morris and William Rich left Hungary in 1859 as young men, settling in Cincinnati. In 1862, their brothers Daniel and Emanuel joined them. After the Civil War, the brothers moved south. William Rich opened a dry goods and clothing store in Atlanta in 1865, while David and Emanuel Rich opened a store in Albany, Georgia. Morris Rich came to Atlanta in 1867, joining his brother William who helped him establish his own dry goods store. David and Emanuel later moved to Atlanta and joined the business. The M. Rich Dry Goods store started modestly, but eventually became the hugely successful Rich’s Department Store, which was run by members of the Rich family until they sold the chain of stores in 1976.

The Hebrew Benevolent Congregation benefited from Atlanta’s extraordinary growth during the Civil War. Atlanta’s population more than doubled during the war, reaching 20,000 people as the city became an important war supply manufacturing and storage center. This role made it a target for the Union Army, which burned the city after its capture in 1864. Atlanta Jews were divided by the war. Some, like David Mayer, were strong secessionists who quickly signed up to fight for the Southern cause. Others like Leo Cahn, who worked as a clerk in Mayer’s store, had no allegiance to a land where he had just recently settled and little interest in fighting for it. Cahn left Atlanta soon after mandatory conscription was implemented. The war ended badly for Atlanta, as General Sherman and his men burned two-thirds of the city.

After the Civil War

Despite this economic blow, Atlanta and its Jewish community soon reemerged from the ashes of the city’s destruction as the Gate City became an economic center of the “New South.” It did not take Atlanta long to rebound from the war. In 1865, the city had 150 stores; by 1869 it had 875 stores. While $3 million worth of goods had been sold in Atlanta in 1859, this annual figure had risen to $35 million by 1872. By 1873, there were five different railroad lines in the city. A growing number of Jews settled in Atlanta seeking to take advantage of this remarkable growth. Their presence was hailed by civic boosters. One local newspaper declared in 1875, “nothing is so indicative of a city’s progress as to see an influx of Jews…because they are thrifty and progressive people who never fail to build up a town they settle in.”

Among these newly arriving Jews were the Rich brothers. Morris and William Rich left Hungary in 1859 as young men, settling in Cincinnati. In 1862, their brothers Daniel and Emanuel joined them. After the Civil War, the brothers moved south. William Rich opened a dry goods and clothing store in Atlanta in 1865, while David and Emanuel Rich opened a store in Albany, Georgia. Morris Rich came to Atlanta in 1867, joining his brother William who helped him establish his own dry goods store. David and Emanuel later moved to Atlanta and joined the business. The M. Rich Dry Goods store started modestly, but eventually became the hugely successful Rich’s Department Store, which was run by members of the Rich family until they sold the chain of stores in 1976.

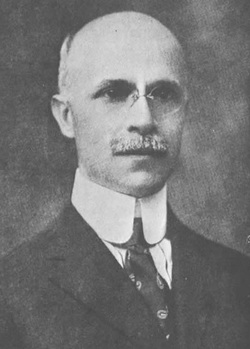

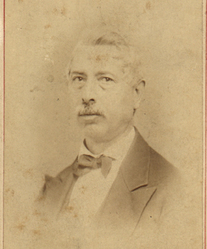

Rabbi David Marx.

Rabbi David Marx. Photo courtesy of The Temple

Jewish Businesses in Atlanta

While most Atlanta Jews did not become as successful as Morris Rich, they too concentrated in commercial trade. According to the historian Steven Hertzberg, in 1880, 71% of adult Jewish men in Atlanta worked in commercial trade; 60% were either business owners or managers. Most Atlanta Jews were in the dry goods or clothing business. One exception was Joseph Jacobs, who opened Jacobs’ Pharmacy after moving to Atlanta in 1884. Jacobs made a name for his business when he began to give pennies as change at a time when they were rare and most Atlanta businesses rounded off their prices to the nearest nickel. When his competitors tried to pressure Jacobs’ suppliers not to sell to him, Jacobs filed a number of successful anti-trust suits. He had opened 10 locations of his pharmacy in Atlanta by 1910. Jacobs was not always such an astute businessman, selling his one third interest in a new soft drink that would eventually become Coca-Cola.

In addition to retail trade, Atlanta Jews were involved in manufacturing. Jacob Elsas moved to Atlanta in 1869 and founded the Fulton Cotton Spinning Company along with three other partners. This company later became the Fulton Bag & Cotton Mill, which at one time employed more people than any other industrial firm in the city. Several other Atlanta Jews owned manufacturing companies as Atlanta transcended the agricultural economy and became a regional industrial center.

The Hebrew Benevolent Congregation

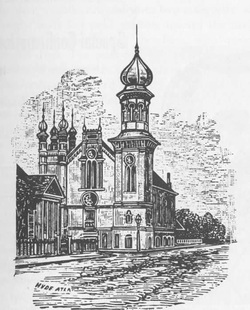

The Hebrew Benevolent Congregation was not as quick to rebound after the war as Atlanta’s economy. The congregation had become dormant during the war. In 1867, Rabbi Isaac Leeser visited Atlanta once again and convinced local Jews to revive the congregation. The group borrowed Torahs from the congregations in Savannah and Augusta and began worshiping in a series of rented halls. In 1875, they bought land on the corner of Garnett and Forsyth streets and built a Moorish-style synagogue out of brick and stone. Atlanta’s mayor and city council took part in the cornerstone laying ceremony in which a local Protestant minister gave the invocation. When completed in 1877, the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation’s synagogue was a symbol of the prominent role Jews were playing in the boom city of the New South.

Most members of the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation were immigrants from central Europe. By 1880, Atlanta had 538 Jews, most all of whom were of German or Austro-Hungarian heritage. As its membership adapted to life in Atlanta, the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation began to wrestle with the issue of how much to change its religious practices to fit its new environment. Initially, the congregation was Orthodox, with separate seating for men and women and services consisting of chanted Hebrew with no musical instruments. By the late 1860s, the congregation began to be influenced by Isaac Mayer Wise, the Cincinnati rabbi who helped establish Reform Judaism in the United States. In 1869, the congregation hired Rabbi David Burgheim, who introduced various reforms, including a mixed-gender choir, sermons in German, and Wise’s Minhag America prayer book. Though Burgheim only stayed for one year, his replacement, Benjamin Bonnheim, continued to move the congregation toward Reform, introducing the confirmation ceremony. Isaac Mayer Wise came to Atlanta himself in 1873 and convinced the congregation to dispense with the traditional second day of Jewish holiday observances. By the time of the synagogue dedication in 1877, the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation had mixed-gender seating and an organ and soon became known by the nickname “The Temple.” It also affiliated with the Union of American Hebrew Congregations.

This embrace of Reform was not a simple and straightforward process. Under the leadership of Rabbi Leo Reich, who came to Atlanta in 1888, the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation moved back toward tradition, restoring the second day of holiday observance and replacing Minhag America with the more traditional Minhag Jastrow prayer book. The congregation even withdrew from the UAHC. This retrenchment was a source of controversy within the congregation, which culminated in a tumultuous congregational meeting in 1895. The Reformers pushed for the prohibition of head coverings and tallit and advocated the use of the new Union Prayer Book, which replaced much of the traditional liturgy with English prayers. When Rabbi Reich refused to accept these changes, he was fired. By the end of the 19th century, most Temple members were native-born or had been in the U.S. for several decades; they had little interest in preserving religious traditionalism. Seeking to cement their identity as a Reform congregation, a narrow majority of the members voted to hire a recently ordained 23-year-old rabbi, David Marx, to lead them. Over his 51-year tenure, Rabbi Marx pushed The Temple further into classical Reform.

Rabbi Marx was very active in the both the Jewish and the larger Atlanta community. He helped to found the Young Men’s Hebrew Association in Atlanta, the Federation of Jewish Charities, and a local chapter of the National Council of Jewish Women. He was also closely involved in efforts to establish free kindergartens in Georgia, mandatory school attendance laws, and improved public health. Marx worked closely with prominent Christian ministers in town as he became recognized by Atlanta’s Gentiles as the leader of Atlanta’s Jewish community. The Temple quickly thrived under Marx’s leadership, growing from 169 members in 1895 to 289 in 1905. In 1902, the congregation moved to a new synagogue on the corner of Pryor and Richardson Streets. In the 1930s, the Temple moved to a grand new synagogue on Peachtree Road on the north side of the city.

While most Atlanta Jews did not become as successful as Morris Rich, they too concentrated in commercial trade. According to the historian Steven Hertzberg, in 1880, 71% of adult Jewish men in Atlanta worked in commercial trade; 60% were either business owners or managers. Most Atlanta Jews were in the dry goods or clothing business. One exception was Joseph Jacobs, who opened Jacobs’ Pharmacy after moving to Atlanta in 1884. Jacobs made a name for his business when he began to give pennies as change at a time when they were rare and most Atlanta businesses rounded off their prices to the nearest nickel. When his competitors tried to pressure Jacobs’ suppliers not to sell to him, Jacobs filed a number of successful anti-trust suits. He had opened 10 locations of his pharmacy in Atlanta by 1910. Jacobs was not always such an astute businessman, selling his one third interest in a new soft drink that would eventually become Coca-Cola.

In addition to retail trade, Atlanta Jews were involved in manufacturing. Jacob Elsas moved to Atlanta in 1869 and founded the Fulton Cotton Spinning Company along with three other partners. This company later became the Fulton Bag & Cotton Mill, which at one time employed more people than any other industrial firm in the city. Several other Atlanta Jews owned manufacturing companies as Atlanta transcended the agricultural economy and became a regional industrial center.

The Hebrew Benevolent Congregation

The Hebrew Benevolent Congregation was not as quick to rebound after the war as Atlanta’s economy. The congregation had become dormant during the war. In 1867, Rabbi Isaac Leeser visited Atlanta once again and convinced local Jews to revive the congregation. The group borrowed Torahs from the congregations in Savannah and Augusta and began worshiping in a series of rented halls. In 1875, they bought land on the corner of Garnett and Forsyth streets and built a Moorish-style synagogue out of brick and stone. Atlanta’s mayor and city council took part in the cornerstone laying ceremony in which a local Protestant minister gave the invocation. When completed in 1877, the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation’s synagogue was a symbol of the prominent role Jews were playing in the boom city of the New South.

Most members of the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation were immigrants from central Europe. By 1880, Atlanta had 538 Jews, most all of whom were of German or Austro-Hungarian heritage. As its membership adapted to life in Atlanta, the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation began to wrestle with the issue of how much to change its religious practices to fit its new environment. Initially, the congregation was Orthodox, with separate seating for men and women and services consisting of chanted Hebrew with no musical instruments. By the late 1860s, the congregation began to be influenced by Isaac Mayer Wise, the Cincinnati rabbi who helped establish Reform Judaism in the United States. In 1869, the congregation hired Rabbi David Burgheim, who introduced various reforms, including a mixed-gender choir, sermons in German, and Wise’s Minhag America prayer book. Though Burgheim only stayed for one year, his replacement, Benjamin Bonnheim, continued to move the congregation toward Reform, introducing the confirmation ceremony. Isaac Mayer Wise came to Atlanta himself in 1873 and convinced the congregation to dispense with the traditional second day of Jewish holiday observances. By the time of the synagogue dedication in 1877, the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation had mixed-gender seating and an organ and soon became known by the nickname “The Temple.” It also affiliated with the Union of American Hebrew Congregations.

This embrace of Reform was not a simple and straightforward process. Under the leadership of Rabbi Leo Reich, who came to Atlanta in 1888, the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation moved back toward tradition, restoring the second day of holiday observance and replacing Minhag America with the more traditional Minhag Jastrow prayer book. The congregation even withdrew from the UAHC. This retrenchment was a source of controversy within the congregation, which culminated in a tumultuous congregational meeting in 1895. The Reformers pushed for the prohibition of head coverings and tallit and advocated the use of the new Union Prayer Book, which replaced much of the traditional liturgy with English prayers. When Rabbi Reich refused to accept these changes, he was fired. By the end of the 19th century, most Temple members were native-born or had been in the U.S. for several decades; they had little interest in preserving religious traditionalism. Seeking to cement their identity as a Reform congregation, a narrow majority of the members voted to hire a recently ordained 23-year-old rabbi, David Marx, to lead them. Over his 51-year tenure, Rabbi Marx pushed The Temple further into classical Reform.

Rabbi Marx was very active in the both the Jewish and the larger Atlanta community. He helped to found the Young Men’s Hebrew Association in Atlanta, the Federation of Jewish Charities, and a local chapter of the National Council of Jewish Women. He was also closely involved in efforts to establish free kindergartens in Georgia, mandatory school attendance laws, and improved public health. Marx worked closely with prominent Christian ministers in town as he became recognized by Atlanta’s Gentiles as the leader of Atlanta’s Jewish community. The Temple quickly thrived under Marx’s leadership, growing from 169 members in 1895 to 289 in 1905. In 1902, the congregation moved to a new synagogue on the corner of Pryor and Richardson Streets. In the 1930s, the Temple moved to a grand new synagogue on Peachtree Road on the north side of the city.

Rabbi Tobias Geffen.

Rabbi Tobias Geffen. Photo courtesy of the The Cuba Archives of theBreman Museum.

A Diverse Jewish Community

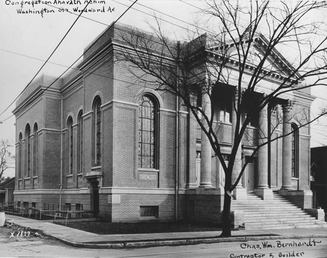

While Rabbi Marx was perceived as a spokesman for the entire Atlanta Jewish community, in reality he represented only a portion of Atlanta’s Jews. During the late 19th century, Eastern European Jews began to arrive in the Atlanta. By the early 20th century, these Yiddish immigrants and their children were a majority of the Atlanta Jewish community, outnumbering the German Jews of Rabbi Marx’s Temple. Most of these recent immigrants had little interest in the Reform worship of the Temple and as early as 1886 they were gathering together to pray on the High Holidays. In 1887, the group officially organized Congregation Ahavath Achim. For 14 years, the congregation met in various rented rooms. In 1901, Ahavath Achim built a synagogue on Piedmont Avenue and Gilmer Street, in the heart of the south side neighborhood where most Yiddish Jews lived. Only a minority of these Jewish immigrants belonged to the Orthodox congregation; most were unaffiliated, possibly because they could not afford the dues.

Ahavath Achim’s early years were often tumultuous, with several dissenting groups breaking off, though only one of these splits was permanent. This division began early. In 1890, a group of Jews from Kovno left the congregation to form B’nai Abraham, though they rejoined Ahavath Achim seven months later. They broke away again in 1897 for a brief time before going back to Ahavath Achim. Another group left in 1896 to form Congregation Chevra Kaddisha, but rejoined Ahavath Achim two years later. In 1905, 15 Ahavath Achim members left the congregation seeking changes to the traditional style of worship. Calling themselves a conservative congregation, the group founded Beth Israel. In 1907, Beth Israel held a dedication for its new synagogue on the corner of Washington and Clarke Street which ended in disaster. While Governor Hoke Smith and Atlanta’s mayor took part in the ceremony, the roof of the synagogue collapsed during a wind and rain storm. This ill-fated beginning did not bode well for Beth Israel. The congregation disbanded in 1920, with some of its members joining The Temple and the remainder rejoining Ahavath Achim.

Many of the disputes within the congregation related to religious observance, especially maintaining the Sabbath, which was often difficult for Jews who owned retail businesses. Members of Ahavath Achim who did not refrain from working on the Sabbath were still allowed Torah honors. This angered more traditional members of the congregation, who were also upset when non-ticket holders were turned away from High Holiday services. In 1902, they broke away to found Shearith Israel. Three years later, the group bought a former church and turned it into a synagogue. Unlike the other splinter groups, Shearith Israel was successful, largely due to their hiring of Tobias Geffen as their rabbi in 1910. Geffen brought tighter regulation of kosher slaughtering, improved Jewish education, and oversaw the construction of a mikvah for the community. For the next 60 years, Rabbi Geffen led Shearith Israel and Orthodox Jews across the southeast, often ruling on disputes in other Jewish communities. Most famously, Rabbi Geffen ruled that Atlanta’s most popular product, Coca-Cola, was kosher, after he was given access to the secret recipe.

While Shearith Israel remained Orthodox, Ahavath Achim, under the leadership of Rabbi Harry Epstein, gradually moved toward Conservative Judaism. Even before the congregation hired Epstein in 1928, the congregation had instituted the confirmation ceremony and Friday night services. Epstein came to Ahavath Achim seven years after the growing congregation built a large new synagogue on Washington Street. Responding to the needs of the second generation immigrants who made up a growing portion of the congregation, Rabbi Epstein gave sermons in English rather than Yiddish and added English prayers to the liturgy. He convinced the congregation to adopt mixed-gender seating and added women to the choir. In 1952, Ahavath Achim formally joined the Conservative movement, though it had been conservative in practice for a long time. Rabbi Epstein served the congregation for 54 years, until his retirement in 1982.

Atlanta received a third wave of Jewish immigrants in the early 20th century. Sephardic Jews, from Turkey and the Isle of Rhodes in particular, began to arrive in Atlanta after the turn of the century. In 1910, 40 Sephardic Jews formed their own congregation, Ahavat Shalom. The Sephardic congregation was not free from the rifts that plagued the Ashkenazic community; in 1912, a group of Turkish Jews left the congregation to form Or Hahyim. Two years later, the two Sephardic congregations merged to form Or Ve Shalom (Light and Peace) in 1914. That year, there were 150 Sephardic Jews in Atlanta, with over half of them coming from Rhodes. Or Ve Shalom dedicated its first synagogue in 1920 at Central and Woodward Avenue.

A small group of Hasidic Jews founded their own Orthodox congregation, Anshi S’fard, in 1913. With a Torah borrowed from Ahavath Achim, the group initially worshiped in the Red Men’s Hall. By the end of 1913, they had bought a building on the corner of Woodward Avenue and King Street. A few years later, the congregation moved several blocks to the west on Woodward Avenue.ants belonged to the Orthodox congregation; most were unaffiliated, possibly because they could not afford the dues.

While Rabbi Marx was perceived as a spokesman for the entire Atlanta Jewish community, in reality he represented only a portion of Atlanta’s Jews. During the late 19th century, Eastern European Jews began to arrive in the Atlanta. By the early 20th century, these Yiddish immigrants and their children were a majority of the Atlanta Jewish community, outnumbering the German Jews of Rabbi Marx’s Temple. Most of these recent immigrants had little interest in the Reform worship of the Temple and as early as 1886 they were gathering together to pray on the High Holidays. In 1887, the group officially organized Congregation Ahavath Achim. For 14 years, the congregation met in various rented rooms. In 1901, Ahavath Achim built a synagogue on Piedmont Avenue and Gilmer Street, in the heart of the south side neighborhood where most Yiddish Jews lived. Only a minority of these Jewish immigrants belonged to the Orthodox congregation; most were unaffiliated, possibly because they could not afford the dues.

Ahavath Achim’s early years were often tumultuous, with several dissenting groups breaking off, though only one of these splits was permanent. This division began early. In 1890, a group of Jews from Kovno left the congregation to form B’nai Abraham, though they rejoined Ahavath Achim seven months later. They broke away again in 1897 for a brief time before going back to Ahavath Achim. Another group left in 1896 to form Congregation Chevra Kaddisha, but rejoined Ahavath Achim two years later. In 1905, 15 Ahavath Achim members left the congregation seeking changes to the traditional style of worship. Calling themselves a conservative congregation, the group founded Beth Israel. In 1907, Beth Israel held a dedication for its new synagogue on the corner of Washington and Clarke Street which ended in disaster. While Governor Hoke Smith and Atlanta’s mayor took part in the ceremony, the roof of the synagogue collapsed during a wind and rain storm. This ill-fated beginning did not bode well for Beth Israel. The congregation disbanded in 1920, with some of its members joining The Temple and the remainder rejoining Ahavath Achim.

Many of the disputes within the congregation related to religious observance, especially maintaining the Sabbath, which was often difficult for Jews who owned retail businesses. Members of Ahavath Achim who did not refrain from working on the Sabbath were still allowed Torah honors. This angered more traditional members of the congregation, who were also upset when non-ticket holders were turned away from High Holiday services. In 1902, they broke away to found Shearith Israel. Three years later, the group bought a former church and turned it into a synagogue. Unlike the other splinter groups, Shearith Israel was successful, largely due to their hiring of Tobias Geffen as their rabbi in 1910. Geffen brought tighter regulation of kosher slaughtering, improved Jewish education, and oversaw the construction of a mikvah for the community. For the next 60 years, Rabbi Geffen led Shearith Israel and Orthodox Jews across the southeast, often ruling on disputes in other Jewish communities. Most famously, Rabbi Geffen ruled that Atlanta’s most popular product, Coca-Cola, was kosher, after he was given access to the secret recipe.

While Shearith Israel remained Orthodox, Ahavath Achim, under the leadership of Rabbi Harry Epstein, gradually moved toward Conservative Judaism. Even before the congregation hired Epstein in 1928, the congregation had instituted the confirmation ceremony and Friday night services. Epstein came to Ahavath Achim seven years after the growing congregation built a large new synagogue on Washington Street. Responding to the needs of the second generation immigrants who made up a growing portion of the congregation, Rabbi Epstein gave sermons in English rather than Yiddish and added English prayers to the liturgy. He convinced the congregation to adopt mixed-gender seating and added women to the choir. In 1952, Ahavath Achim formally joined the Conservative movement, though it had been conservative in practice for a long time. Rabbi Epstein served the congregation for 54 years, until his retirement in 1982.

Atlanta received a third wave of Jewish immigrants in the early 20th century. Sephardic Jews, from Turkey and the Isle of Rhodes in particular, began to arrive in Atlanta after the turn of the century. In 1910, 40 Sephardic Jews formed their own congregation, Ahavat Shalom. The Sephardic congregation was not free from the rifts that plagued the Ashkenazic community; in 1912, a group of Turkish Jews left the congregation to form Or Hahyim. Two years later, the two Sephardic congregations merged to form Or Ve Shalom (Light and Peace) in 1914. That year, there were 150 Sephardic Jews in Atlanta, with over half of them coming from Rhodes. Or Ve Shalom dedicated its first synagogue in 1920 at Central and Woodward Avenue.

A small group of Hasidic Jews founded their own Orthodox congregation, Anshi S’fard, in 1913. With a Torah borrowed from Ahavath Achim, the group initially worshiped in the Red Men’s Hall. By the end of 1913, they had bought a building on the corner of Woodward Avenue and King Street. A few years later, the congregation moved several blocks to the west on Woodward Avenue.ants belonged to the Orthodox congregation; most were unaffiliated, possibly because they could not afford the dues.

Ahavath Achim's 1921 synagogue.

Ahavath Achim's 1921 synagogue. Photo courtesy of the Cuba Archives of the Breman Museum.

The Early 20th Century

Atlanta’s Jewish community in the early 20th century was concentrated in business. There were 214 male members of The Temple in 1917, and 80% of them were either business owners, managers or professionals. Among business owners and managers, 43% were in commercial trade, while 39% worked in the manufacturing business. This tendency toward self-employment was even true for the poorer Eastern European Jews in Atlanta. As early as 1900, 63% of Russian-born males in Atlanta engaged in commercial trade. Many started out as peddlers and then opened small retail stores in the city. These Eastern European Jews enjoyed economic mobility, usually moving up into the middle class within one generation. Stephen Hertzberg has studied a group of 62 Yiddish Jews in Atlanta between 1896 and 1911. In 1896, 67% of these Jews had less than $50 in total wealth; by 1911, only 37% were worth less than $50, while 30% were worth over $3000. The small Sephardic community clustered in skilled manual labor, especially shoemaking. According to Hertzberg, in 1914, 67% of the employed Sephardic Jews in Atlanta were shoemakers, with most owning their own small shops. Another 20% owned restaurants, saloons, or fruit stands.

David Yampolsky’s experience was characteristic of the path of economic mobility which many Jewish immigrants traveled in Atlanta. Yampolsky had been a manual laborer in Russia and in New York, where he had lived briefly after coming to the U.S. He moved south after his uncle, who had already settled in the city, convinced him that there was more economic opportunity in Atlanta. On his first day of work in Atlanta, Yampolsky purchased merchandise from a local Jewish-owned peddler supply store, got on a random street car, rode to the end of its route, and began to go door-to-door to sell his merchandise. While he did not know much English, he memorized the names of all of the products he was selling and soon learned the meaning of the phrase, “got no money.” Nevertheless, Yampolsky made a good profit on his first day, $3, and his business career had begun. A few years later, he opened his own grocery store along with six other immigrant partners.

Atlanta’s Jewish community in the early 20th century was concentrated in business. There were 214 male members of The Temple in 1917, and 80% of them were either business owners, managers or professionals. Among business owners and managers, 43% were in commercial trade, while 39% worked in the manufacturing business. This tendency toward self-employment was even true for the poorer Eastern European Jews in Atlanta. As early as 1900, 63% of Russian-born males in Atlanta engaged in commercial trade. Many started out as peddlers and then opened small retail stores in the city. These Eastern European Jews enjoyed economic mobility, usually moving up into the middle class within one generation. Stephen Hertzberg has studied a group of 62 Yiddish Jews in Atlanta between 1896 and 1911. In 1896, 67% of these Jews had less than $50 in total wealth; by 1911, only 37% were worth less than $50, while 30% were worth over $3000. The small Sephardic community clustered in skilled manual labor, especially shoemaking. According to Hertzberg, in 1914, 67% of the employed Sephardic Jews in Atlanta were shoemakers, with most owning their own small shops. Another 20% owned restaurants, saloons, or fruit stands.

David Yampolsky’s experience was characteristic of the path of economic mobility which many Jewish immigrants traveled in Atlanta. Yampolsky had been a manual laborer in Russia and in New York, where he had lived briefly after coming to the U.S. He moved south after his uncle, who had already settled in the city, convinced him that there was more economic opportunity in Atlanta. On his first day of work in Atlanta, Yampolsky purchased merchandise from a local Jewish-owned peddler supply store, got on a random street car, rode to the end of its route, and began to go door-to-door to sell his merchandise. While he did not know much English, he memorized the names of all of the products he was selling and soon learned the meaning of the phrase, “got no money.” Nevertheless, Yampolsky made a good profit on his first day, $3, and his business career had begun. A few years later, he opened his own grocery store along with six other immigrant partners.

Spanish Ball at the Standard Club c. 1925.

Spanish Ball at the Standard Club c. 1925. Photo courtesy of the Cuba Archives of the Breman Museum

Jewish Organizations

Yiddish Jews like Yampolsky lived in an almost separate world than the “German Jews” who belonged to the Temple. While the German Jews worked to help assimilate the Eastern European immigrants who came to Atlanta, they also tended to look down on them and erected social barriers to keep them separate. The Hebrew Relief Society and the Hebrew Ladies Benevolent Society, run by German Jews, assisted those Jewish immigrants who were in need. Tensions sometimes arose between the two communities. When the Council of Jewish Women opened a Sabbath School for the immigrants, Yiddish Jews were offended. The editor of the local Jewish newspaper defended the school, claiming that these newly arrived immigrants were “ignorant” and “coarse” and that “we want to make good American citizens out of our Russian brothers.” The city’s German-Jewish elite founded the Standard Club and bought a mansion for their clubhouse. Yiddish Jews were largely excluded from the Standard Club until the hardship of the Great Depression caused them to end this discrimination. Yiddish Jews founded their own social club, the Progressive Club, in 1913. By most accounts, this social barrier between German and Yiddish Jews did not die out until World War II.

Yiddish Jews like Yampolsky lived in an almost separate world than the “German Jews” who belonged to the Temple. While the German Jews worked to help assimilate the Eastern European immigrants who came to Atlanta, they also tended to look down on them and erected social barriers to keep them separate. The Hebrew Relief Society and the Hebrew Ladies Benevolent Society, run by German Jews, assisted those Jewish immigrants who were in need. Tensions sometimes arose between the two communities. When the Council of Jewish Women opened a Sabbath School for the immigrants, Yiddish Jews were offended. The editor of the local Jewish newspaper defended the school, claiming that these newly arrived immigrants were “ignorant” and “coarse” and that “we want to make good American citizens out of our Russian brothers.” The city’s German-Jewish elite founded the Standard Club and bought a mansion for their clubhouse. Yiddish Jews were largely excluded from the Standard Club until the hardship of the Great Depression caused them to end this discrimination. Yiddish Jews founded their own social club, the Progressive Club, in 1913. By most accounts, this social barrier between German and Yiddish Jews did not die out until World War II.

David Mayer.

David Mayer. Photo courtesy of the Cuba Archives of the Breman Museum.

Despite these tensions, the German and Yiddish Jews cooperated in the creation of the Jewish Educational Alliance, which arose from a 1909 merger between the Russian-founded Hebrew Institute and the German-founded Free Kindergarten and Social Settlement. The purposes of the new institution included Americanization of recent immigrants as well as offering a place for manual training classes, Hebrew language instruction, “clean and wholesome amusement and recreation,” and meeting rooms for the city’s Jewish clubs and organizations. When the Jewish Educational Alliance (JEA) was completed in 1911, extra money raised for the project was used to endow a free health clinic in the building.

Located on Capitol Street, in the center of Atlanta’s Jewish enclave, the JEA acted as both a social settlement and a community center for local Jews. It held citizenship and English classes at night as well as cooking classes to acquaint Jewish women with the foods and cooking styles of the South. It later became more of a community center than an immigrant help center, hosting social, theatrical, and athletic events. The JEA became the center of the local Jewish community. In just one month in 1914, over 14,000 people attended some event or program in the building.

Located on Capitol Street, in the center of Atlanta’s Jewish enclave, the JEA acted as both a social settlement and a community center for local Jews. It held citizenship and English classes at night as well as cooking classes to acquaint Jewish women with the foods and cooking styles of the South. It later became more of a community center than an immigrant help center, hosting social, theatrical, and athletic events. The JEA became the center of the local Jewish community. In just one month in 1914, over 14,000 people attended some event or program in the building.

JEA Basketball team, 1935.

JEA Basketball team, 1935. Photo courtesy of the Cuba Archives of the Breman Museum.

The Atlanta Jewish community established institutions that helped fund and manage Jewish charities in the city. In 1905, Atlanta Jews founded the Federation of Jewish Charities as an umbrella organization that helped to coordinate Jewish fundraising and charity in the city. Although it has undergone several reorganizations over the years, the Atlanta Jewish Federation still serves the community today. The Jewish community also worked together to support the Hebrew Orphan’s Home in Atlanta. Founded by the District Grand Lodge of the B’nai B’rith, the home was constructed in Atlanta in 1889 after the city raised the most money to build it, beating out Richmond and Washington, D.C. Almost 400 children lived in the home during its first 25 years; two-thirds came from outside of Atlanta and most were of Eastern European background. By 1910, the home began shifting toward supporting foster care and financial support of widows. By 1930, the Hebrew Orphan’s Home was closed.

Jewish Orphan's Home

Jewish Orphan's Home

Civic Engagement

In addition to caring for their own, Atlanta Jews were also involved in the larger society. Several Jews served on the city council in the late 19th century, including Jacob Haas and Joseph Hirsch. Aaron Haas served on the city council and became the city’s first mayor pro tem in 1875. David Mayer helped to create Atlanta’s public school system and served on the board of education from 1869 until his death in 1890. Several other Jews served on the school board during the 1890s and 1900s, including Joseph Hirsch and Oscar Pappenheimer. Jacob Elsas had the idea to build a public hospital in 1888 and kicked off the fundraising effort with a $1000 contribution that helped establish the city’s Henry Grady Memorial Hospital. Joseph Hirsch served as chairman of Grady’s board and helped convince the city government to subsidize the hospital.

In addition to caring for their own, Atlanta Jews were also involved in the larger society. Several Jews served on the city council in the late 19th century, including Jacob Haas and Joseph Hirsch. Aaron Haas served on the city council and became the city’s first mayor pro tem in 1875. David Mayer helped to create Atlanta’s public school system and served on the board of education from 1869 until his death in 1890. Several other Jews served on the school board during the 1890s and 1900s, including Joseph Hirsch and Oscar Pappenheimer. Jacob Elsas had the idea to build a public hospital in 1888 and kicked off the fundraising effort with a $1000 contribution that helped establish the city’s Henry Grady Memorial Hospital. Joseph Hirsch served as chairman of Grady’s board and helped convince the city government to subsidize the hospital.

Leo Frank during the trial

Leo Frank during the trial

Anti-Semitism in Atlanta

Despite the significant contribution of Atlanta Jews to city life, according to Steven Hertzberg, anti-Semitism was on the rise in Atlanta by the turn of the century. Jewish candidates were increasingly losing local elections in the first decade of the 20th century; in several cases their opponents were explicitly anti-Semitic in their appeals. One of the major political issues of the time was alcohol prohibition; Jews were overwhelmingly on the “wet” side of the debate. Public campaigns against alcohol sometimes took an anti-Semitic tone. After the 1906 riot, in which white mobs terrorized the city’s black population, some blamed Jewish saloon keepers for serving alcohol to blacks; after the riot, several Jewish saloon owners lost their licenses.

This growing anti-Semitism would soon peak during the Leo Frank Case, which ended in violent tragedy. Raised in New York, Leo Frank moved to Atlanta as a young adult, where he worked as a superintendent at his uncle’s pencil factory. On April 26, 1913, Confederate Memorial Day, a 13-year old employee, Mary Phagan, was found murdered in the factory basement. Suspicion soon fell on Frank, who was arrested and indicted for the murder a few weeks later. The chief witness against him was Jim Conley, an African American who worked as a janitor at the factory. Conley claimed that Frank ordered him to help move Phagan’s body. It was extremely rare in Jim Crow Georgia for a white suspect to be prosecuted for a capital crime on the testimony of a black witness.

The case became a major news story in Atlanta, covered in detail by the local newspapers. Attacks on Frank, especially in populist leader Tom Watson’s Jeffersonian newspaper, often took an anti-Semitic tone. Scurrilous rumors about Frank were printed and widely discussed in the community. During the trial, Frank’s defense lawyers challenged the veracity of Conley, often in racial terms. Despite Conley’s changing story, the jury voted to convict Frank for the murder of Mary Phagan and sentenced him to death after less than four hours of deliberations. As the verdict was read, a mob outside the courthouse cheered wildly. Frank appealed the verdict all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, but was denied.

Under tremendous pressure from both sides, Governor John Slaton of Georgia studied the case in depth and found serious doubt about Frank’s guilt. In the final week of his term of office, Slaton decided to commute Frank’s sentence to life in prison, which enraged many Atlantans, who burned the governor in effigy. On August 19, 1915, a vigilante group calling itself the “Knights of Mary Phagan” kidnapped Frank from the state prison farm, took him to Marietta, a small town outside of Atlanta where Phagan was from, and lynched him. The ringleaders of the lynching were among the prominent political and business leaders in the state, including the son of a U.S. Senator who was a former mayor of Marietta. The leaders of the Knights of Mary Phagan helped to revive the Ku Klux Klan on Stone Mountain in the aftermath of the Frank lynching. National Jewish leaders, alarmed by the anti-Semitism that swirled around the case, established the Anti-Defamation League.

Atlanta Jews, especially the assimilated and successful members of the Temple, were shocked and terrorized by the lynching. Frank was an assimilated, American-born Jew who was president of the local Golden Gate Lodge of B’nai B’rith. His lynching convinced many Atlanta Jews that they would never be safe from anti-Semitism. In the decades after the lynching of Leo Frank, Atlanta Jews took a step back from the political sphere. It would be another two decades before an Atlanta Jew would run for office again. According to Steven Hertzberg, the anti-Semitism unleashed during the Frank case “demonstrated the vulnerability of Atlanta’s Jews” and “hung like a threatening cloud over the Jewish community” for several decades. Eli Evans has written that the lynching “left a deep and lasting scar on the soul of the immigrant generation.” When Warner Brothers released a movie about the Frank case in 1937, local Jewish leaders fought successfully to keep it from playing in Atlanta.

Despite the significant contribution of Atlanta Jews to city life, according to Steven Hertzberg, anti-Semitism was on the rise in Atlanta by the turn of the century. Jewish candidates were increasingly losing local elections in the first decade of the 20th century; in several cases their opponents were explicitly anti-Semitic in their appeals. One of the major political issues of the time was alcohol prohibition; Jews were overwhelmingly on the “wet” side of the debate. Public campaigns against alcohol sometimes took an anti-Semitic tone. After the 1906 riot, in which white mobs terrorized the city’s black population, some blamed Jewish saloon keepers for serving alcohol to blacks; after the riot, several Jewish saloon owners lost their licenses.

This growing anti-Semitism would soon peak during the Leo Frank Case, which ended in violent tragedy. Raised in New York, Leo Frank moved to Atlanta as a young adult, where he worked as a superintendent at his uncle’s pencil factory. On April 26, 1913, Confederate Memorial Day, a 13-year old employee, Mary Phagan, was found murdered in the factory basement. Suspicion soon fell on Frank, who was arrested and indicted for the murder a few weeks later. The chief witness against him was Jim Conley, an African American who worked as a janitor at the factory. Conley claimed that Frank ordered him to help move Phagan’s body. It was extremely rare in Jim Crow Georgia for a white suspect to be prosecuted for a capital crime on the testimony of a black witness.

The case became a major news story in Atlanta, covered in detail by the local newspapers. Attacks on Frank, especially in populist leader Tom Watson’s Jeffersonian newspaper, often took an anti-Semitic tone. Scurrilous rumors about Frank were printed and widely discussed in the community. During the trial, Frank’s defense lawyers challenged the veracity of Conley, often in racial terms. Despite Conley’s changing story, the jury voted to convict Frank for the murder of Mary Phagan and sentenced him to death after less than four hours of deliberations. As the verdict was read, a mob outside the courthouse cheered wildly. Frank appealed the verdict all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, but was denied.

Under tremendous pressure from both sides, Governor John Slaton of Georgia studied the case in depth and found serious doubt about Frank’s guilt. In the final week of his term of office, Slaton decided to commute Frank’s sentence to life in prison, which enraged many Atlantans, who burned the governor in effigy. On August 19, 1915, a vigilante group calling itself the “Knights of Mary Phagan” kidnapped Frank from the state prison farm, took him to Marietta, a small town outside of Atlanta where Phagan was from, and lynched him. The ringleaders of the lynching were among the prominent political and business leaders in the state, including the son of a U.S. Senator who was a former mayor of Marietta. The leaders of the Knights of Mary Phagan helped to revive the Ku Klux Klan on Stone Mountain in the aftermath of the Frank lynching. National Jewish leaders, alarmed by the anti-Semitism that swirled around the case, established the Anti-Defamation League.

Atlanta Jews, especially the assimilated and successful members of the Temple, were shocked and terrorized by the lynching. Frank was an assimilated, American-born Jew who was president of the local Golden Gate Lodge of B’nai B’rith. His lynching convinced many Atlanta Jews that they would never be safe from anti-Semitism. In the decades after the lynching of Leo Frank, Atlanta Jews took a step back from the political sphere. It would be another two decades before an Atlanta Jew would run for office again. According to Steven Hertzberg, the anti-Semitism unleashed during the Frank case “demonstrated the vulnerability of Atlanta’s Jews” and “hung like a threatening cloud over the Jewish community” for several decades. Eli Evans has written that the lynching “left a deep and lasting scar on the soul of the immigrant generation.” When Warner Brothers released a movie about the Frank case in 1937, local Jewish leaders fought successfully to keep it from playing in Atlanta.

Workmen's Circle School

Workmen's Circle School Photo courtesy of the Cuba Archives of the Breman Museum .

The Community Grows

Despite the fears stemming from the Frank lynching, Atlanta’s Jewish community continued to grow. In 1910 there had been 4,000 Jews, by 1937 there were 12,000. While they were still a small percentage of the city’s overall population, Jews made up over a third of Atlanta’s foreign-born population in 1920. Divisions still existed within the community, especially over the issue of Zionism. After the first Zionist congress was held in Basel, Switzerland in 1897, Atlanta Jews had very different reactions. Rabbi David Marx of the Temple led his congregation to pass a resolution opposing Zionism, arguing that the movement was anathema to Jews who wished to assimilate and live as Americans. His strong anti-Zionism was extremely influential and played a significant role in early Zionism’s failure to attract much support in Atlanta.

Around the same time as the Temple’s declaration, a group of 50 Jewish immigrants founded the Atlanta Zionist Society. The society, which met at the Orthodox synagogue Ahavath Achim, was small and not very active, though when guest speakers came through town, they could attract a large crowd. By the early 20th century, it had become inactive. Atlanta women founded the Daughters of Zion in 1905. These groups were small and went through long periods of inactivity. Zionism did not gain significant popularity in Atlanta until the 1920s. In 1920, a mass meeting to celebrate the San Remo Conference, during which the World War I allies expressed support for a Jewish homeland in Palestine, drew over 2,000 people. During the celebration, the stage was decorated with American, British, and Zionist flags and Jewish children sang both the Zionist and American national anthems. Atlanta Zionists focused largely on raising money for the Jewish settlement in Palestine. In 1916, Atlanta women founded a chapter of Hadassah; by 1927, it had 300 members.

Some Atlanta Jews were drawn to socialist groups. In 1910, a small group of socialist immigrants, who opposed the idea of a Jewish state, founded a chapter of the Arbeter Ring (Workmen's Circle), a socialist benevolent society that stressed working class politics and Yiddish language and culture. M.J. Merlin and Samuel Yampolsky were the leaders of the local chapter, which had 97 members by 1915. Few if any of the members were wage laborers; most owned small retail businesses. The group even had a Yiddish school for members' children. As elsewhere, Atlanta's Arbeter Ring membership peaked in the 1920s, shortly after the end of Jewish mass migration from Eastern Europe. Though the group began to decline in the 1930s, a local branch remained active into the 1970s. Despite the group's efforts with its school, many children of Jewish immigrants had little interest in the organization. Other Yiddish immigrants founded a chapter of the Farband, or Jewish National Workmen’s Alliance, which shared the socialist ideology of the Arbeter Ring but also supported the Zionist cause. The Farband and Arbeter Ring sometimes partnered to bring in major Jewish socialist speakers to the city, including Baruch Vladeck and Chaim Zhitlowsky.

As Atlanta’s Jewish community assimilated and prospered economically, these socialist groups largely died out. Atlanta Jews also moved from the city’s south side to nicer areas in the northern part of the city. The German Jews moved first, but were soon followed by Eastern European Jews. By the late 1920, the north side was becoming the center of the Jewish community in Atlanta. In 1945, two-thirds of Atlanta Jews lived in the northeastern part of the city, while most of those remaining on the south side planned to move north eventually. The city’s congregations followed suit. Shearith Israel moved to University Avenue in 1946 to be closer to its membership which had largely left the south side of the city. Or VeShalom moved to a larger building on North Highland Avenue in 1948. In 1958, Ahavath Achim, which had over 1500 members at the time, followed its membership and built a new synagogue in the northeast part of the city.

As Congregation Ahavath Achim began shifting towards Conservative Judaism in the late 1920s, a group of Orthodox Jews began holding High Holiday and then daily and weekly Shabbat services in private homes or storefronts in the early 1930s. In 1944, this group formally established Congregation Beth Jacob, using a remodeled apartment building as a synagogue. The sanctuary was expanded twice and an assembly hall, rabbi’s office, and classrooms were constructed soon thereafter. Beth Jacob’s second rabbi, Emanuel Feldman, arrived in 1952 and served the congregation until his retirement in 1991. He saw the temple through a period of growth followed by the construction of a new synagogue in 1956 and, with a membership of 190 households, the dedication of another new facility in 1962. Beth Jacobs’ membership reached 400 families in 1970. During the 1980s, membership reached 500 families.

Despite the fears stemming from the Frank lynching, Atlanta’s Jewish community continued to grow. In 1910 there had been 4,000 Jews, by 1937 there were 12,000. While they were still a small percentage of the city’s overall population, Jews made up over a third of Atlanta’s foreign-born population in 1920. Divisions still existed within the community, especially over the issue of Zionism. After the first Zionist congress was held in Basel, Switzerland in 1897, Atlanta Jews had very different reactions. Rabbi David Marx of the Temple led his congregation to pass a resolution opposing Zionism, arguing that the movement was anathema to Jews who wished to assimilate and live as Americans. His strong anti-Zionism was extremely influential and played a significant role in early Zionism’s failure to attract much support in Atlanta.

Around the same time as the Temple’s declaration, a group of 50 Jewish immigrants founded the Atlanta Zionist Society. The society, which met at the Orthodox synagogue Ahavath Achim, was small and not very active, though when guest speakers came through town, they could attract a large crowd. By the early 20th century, it had become inactive. Atlanta women founded the Daughters of Zion in 1905. These groups were small and went through long periods of inactivity. Zionism did not gain significant popularity in Atlanta until the 1920s. In 1920, a mass meeting to celebrate the San Remo Conference, during which the World War I allies expressed support for a Jewish homeland in Palestine, drew over 2,000 people. During the celebration, the stage was decorated with American, British, and Zionist flags and Jewish children sang both the Zionist and American national anthems. Atlanta Zionists focused largely on raising money for the Jewish settlement in Palestine. In 1916, Atlanta women founded a chapter of Hadassah; by 1927, it had 300 members.

Some Atlanta Jews were drawn to socialist groups. In 1910, a small group of socialist immigrants, who opposed the idea of a Jewish state, founded a chapter of the Arbeter Ring (Workmen's Circle), a socialist benevolent society that stressed working class politics and Yiddish language and culture. M.J. Merlin and Samuel Yampolsky were the leaders of the local chapter, which had 97 members by 1915. Few if any of the members were wage laborers; most owned small retail businesses. The group even had a Yiddish school for members' children. As elsewhere, Atlanta's Arbeter Ring membership peaked in the 1920s, shortly after the end of Jewish mass migration from Eastern Europe. Though the group began to decline in the 1930s, a local branch remained active into the 1970s. Despite the group's efforts with its school, many children of Jewish immigrants had little interest in the organization. Other Yiddish immigrants founded a chapter of the Farband, or Jewish National Workmen’s Alliance, which shared the socialist ideology of the Arbeter Ring but also supported the Zionist cause. The Farband and Arbeter Ring sometimes partnered to bring in major Jewish socialist speakers to the city, including Baruch Vladeck and Chaim Zhitlowsky.

As Atlanta’s Jewish community assimilated and prospered economically, these socialist groups largely died out. Atlanta Jews also moved from the city’s south side to nicer areas in the northern part of the city. The German Jews moved first, but were soon followed by Eastern European Jews. By the late 1920, the north side was becoming the center of the Jewish community in Atlanta. In 1945, two-thirds of Atlanta Jews lived in the northeastern part of the city, while most of those remaining on the south side planned to move north eventually. The city’s congregations followed suit. Shearith Israel moved to University Avenue in 1946 to be closer to its membership which had largely left the south side of the city. Or VeShalom moved to a larger building on North Highland Avenue in 1948. In 1958, Ahavath Achim, which had over 1500 members at the time, followed its membership and built a new synagogue in the northeast part of the city.

As Congregation Ahavath Achim began shifting towards Conservative Judaism in the late 1920s, a group of Orthodox Jews began holding High Holiday and then daily and weekly Shabbat services in private homes or storefronts in the early 1930s. In 1944, this group formally established Congregation Beth Jacob, using a remodeled apartment building as a synagogue. The sanctuary was expanded twice and an assembly hall, rabbi’s office, and classrooms were constructed soon thereafter. Beth Jacob’s second rabbi, Emanuel Feldman, arrived in 1952 and served the congregation until his retirement in 1991. He saw the temple through a period of growth followed by the construction of a new synagogue in 1956 and, with a membership of 190 households, the dedication of another new facility in 1962. Beth Jacobs’ membership reached 400 families in 1970. During the 1980s, membership reached 500 families.

Mrs. & Mr. Ben Massell with Eleanor Roosevelt at Israel Bond

Dinner, 1962.

Mrs. & Mr. Ben Massell with Eleanor Roosevelt at Israel Bond

Dinner, 1962. Photo courtesy of the Cuba Archives of the Breman Museum.

After World War II

A study of the Jewish population of Atlanta in 1947 reveals a large but stable community. An estimated 10,217 Jews lived in Atlanta just after World War II. Over half of Atlanta’s Jewish families had been living in the area for over 20 years, while 15% had been living in Atlanta for five years of less. Jews enjoyed relatively high economic status, with 54% owning their own homes, about twice as high as the overall rate in Atlanta. Over half of Atlanta Jews who worked owned their own businesses; 47% worked in retail or wholesale trade while 13% were professionals. One of the most successful businessmen in the city was Ben Massell, a real estate mogul who helped to transform the physical landscape of Atlanta. Born in Lithuania, Massell came to Atlanta as a young child with his family. Labeled by Mayor William Hartsfield as “Atlanta’s one-man boom,” Massell built over 1000 buildings in the city.

After World War II, most Atlanta Jews were active in the Jewish community. According to the 1947 population study, only 6% of Jewish adults in Atlanta did not belong to any Jewish organization. 56% belonged to a synagogue, while 40% belonged to a Zionist organization. There were six congregations in the city at the time, five of which were Orthodox. 38% belonged to one of the three Jewish social organizations in the city. 61% of adult Jews belonged to two or more Jewish organizations. Contributing to the stability of Atlanta’s Jewish community were the tenures of the three rabbis, David Marx, Tobias Geffen, and Harry Epstein, who led the three largest congregations in the city for a combined 165 years.

A study of the Jewish population of Atlanta in 1947 reveals a large but stable community. An estimated 10,217 Jews lived in Atlanta just after World War II. Over half of Atlanta’s Jewish families had been living in the area for over 20 years, while 15% had been living in Atlanta for five years of less. Jews enjoyed relatively high economic status, with 54% owning their own homes, about twice as high as the overall rate in Atlanta. Over half of Atlanta Jews who worked owned their own businesses; 47% worked in retail or wholesale trade while 13% were professionals. One of the most successful businessmen in the city was Ben Massell, a real estate mogul who helped to transform the physical landscape of Atlanta. Born in Lithuania, Massell came to Atlanta as a young child with his family. Labeled by Mayor William Hartsfield as “Atlanta’s one-man boom,” Massell built over 1000 buildings in the city.

After World War II, most Atlanta Jews were active in the Jewish community. According to the 1947 population study, only 6% of Jewish adults in Atlanta did not belong to any Jewish organization. 56% belonged to a synagogue, while 40% belonged to a Zionist organization. There were six congregations in the city at the time, five of which were Orthodox. 38% belonged to one of the three Jewish social organizations in the city. 61% of adult Jews belonged to two or more Jewish organizations. Contributing to the stability of Atlanta’s Jewish community were the tenures of the three rabbis, David Marx, Tobias Geffen, and Harry Epstein, who led the three largest congregations in the city for a combined 165 years.

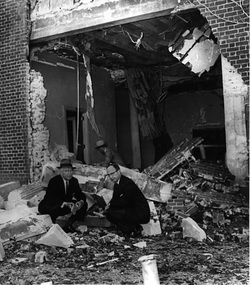

Mayor Hartsfield with Rabbi Rothschild after bombing. Photo

courtesy of The Temple

Mayor Hartsfield with Rabbi Rothschild after bombing. Photo

courtesy of The Temple

Civil Rights and White Supremacist Terror

Rabbi Marx was succeeded by Jacob Rothschild, who came to The Temple in 1946. Rothschild quickly became a critic of Southern segregation. After the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education ruling in 1954, Rothschild called on the state of Georgia to abide by the decision and integrate the public schools. As Rothschild became increasingly outspoken on the issue of civil rights, an underground group of white supremacists began a campaign of terror against Jewish communities across the South. Unexploded dynamite was found in synagogues in Charlotte and Gastonia, North Carolina, and Birmingham, Alabama. Racists bombed a synagogue in Miami and the Jewish Community Center in Nashville.

On October 12, 1958, a group of white supremacists calling themselves the “Confederate Underground” bombed The Temple in Atlanta. Although no one was hurt, the bomb caused over $100,000 in damage. Mayor William Hartsfield denounced the attack, which had shocked many Atlantans who did not want their city associated with hatred and violence. Ralph McGill, the editor of the Atlanta Journal Constitution, condemned the attack in a Pulitzer Prize winning editorial in which he blamed the bombing on a climate of racial hatred that white Atlanta had allowed to fester. Many in the Christian community expressed solidarity with the Temple, several made donations to the congregation to help them rebuild, even though the Temple did not ask for financial support since the damage was covered by insurance.

In contrast to the lynching of Leo Frank, the Temple bombing did not scare Atlanta Jews away from the public sphere. During the first Shabbat service after the bombing, Rabbi Rothschild gave a sermon entitled “And None Shall Make Them Afraid.” Instead of being silenced, Rothschild became more outspoken on civil rights. He publicly supported the work of Martin Luther King Jr., even befriending the minister after he moved to Atlanta in 1960. Temple members who had been uncomfortable with Rothschild’s activism rallied behind their rabbi after the bombing. The outpouring of support from the larger community comforted Atlanta Jews. Rabbi Rothschild’s wife Janice called it “the bomb that healed.”

Rabbi Marx was succeeded by Jacob Rothschild, who came to The Temple in 1946. Rothschild quickly became a critic of Southern segregation. After the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education ruling in 1954, Rothschild called on the state of Georgia to abide by the decision and integrate the public schools. As Rothschild became increasingly outspoken on the issue of civil rights, an underground group of white supremacists began a campaign of terror against Jewish communities across the South. Unexploded dynamite was found in synagogues in Charlotte and Gastonia, North Carolina, and Birmingham, Alabama. Racists bombed a synagogue in Miami and the Jewish Community Center in Nashville.

On October 12, 1958, a group of white supremacists calling themselves the “Confederate Underground” bombed The Temple in Atlanta. Although no one was hurt, the bomb caused over $100,000 in damage. Mayor William Hartsfield denounced the attack, which had shocked many Atlantans who did not want their city associated with hatred and violence. Ralph McGill, the editor of the Atlanta Journal Constitution, condemned the attack in a Pulitzer Prize winning editorial in which he blamed the bombing on a climate of racial hatred that white Atlanta had allowed to fester. Many in the Christian community expressed solidarity with the Temple, several made donations to the congregation to help them rebuild, even though the Temple did not ask for financial support since the damage was covered by insurance.

In contrast to the lynching of Leo Frank, the Temple bombing did not scare Atlanta Jews away from the public sphere. During the first Shabbat service after the bombing, Rabbi Rothschild gave a sermon entitled “And None Shall Make Them Afraid.” Instead of being silenced, Rothschild became more outspoken on civil rights. He publicly supported the work of Martin Luther King Jr., even befriending the minister after he moved to Atlanta in 1960. Temple members who had been uncomfortable with Rothschild’s activism rallied behind their rabbi after the bombing. The outpouring of support from the larger community comforted Atlanta Jews. Rabbi Rothschild’s wife Janice called it “the bomb that healed.”

Sam Massell

Sam Massell

Jewish Political Involvement

In the aftermath of the bombing, Jews became active once again in local politics.Sam Massell was elected vice mayor in 1961. Four years later, he was re-elected with 72% of the vote. In 1969, he ran for mayor in a bitter campaign in which Massell accused his political opponents of anti-Semitism. Massell ran against the downtown interests and the city’s “old boy” power structure. He won the election with 90% of the black vote and only 25% of the white vote. In 1973, Massell was challenged by the African American vice mayor, Maynard Jackson. After a racially charged campaign, Massell was defeated by Jackson, who became Atlanta’s first black mayor. In 1974, attorney Elliott Levitas, who had served nine years in the Georgia legislature, was elected to his first of five terms in the U.S. House of Representatives from Atlanta. When Georgia Governor Jimmy Carter won the presidency in 1976, he took several Jewish advisors from Atlanta with him to Washington, including Robert Lipshutz, who was White House Counsel, and Stuart Eizenstat, who was his Chief Domestic Policy Advisor.

In the aftermath of the bombing, Jews became active once again in local politics.Sam Massell was elected vice mayor in 1961. Four years later, he was re-elected with 72% of the vote. In 1969, he ran for mayor in a bitter campaign in which Massell accused his political opponents of anti-Semitism. Massell ran against the downtown interests and the city’s “old boy” power structure. He won the election with 90% of the black vote and only 25% of the white vote. In 1973, Massell was challenged by the African American vice mayor, Maynard Jackson. After a racially charged campaign, Massell was defeated by Jackson, who became Atlanta’s first black mayor. In 1974, attorney Elliott Levitas, who had served nine years in the Georgia legislature, was elected to his first of five terms in the U.S. House of Representatives from Atlanta. When Georgia Governor Jimmy Carter won the presidency in 1976, he took several Jewish advisors from Atlanta with him to Washington, including Robert Lipshutz, who was White House Counsel, and Stuart Eizenstat, who was his Chief Domestic Policy Advisor.

The Jewish Community in Atlanta Today

In recent years, Jews have remained active in Atlanta Metropolitan Area. Sam Olens is a prominent Georgia politician. As chairman of the Cobb County Commission, Olens worked to pass two bond referendums for county parks and convinced voters to pass a sales tax increase to improve local roads. In 2004, Olens was reelected with over 80% of the vote and ran unopposed in 2008. Building on this local success, Olens was sworn in as Attorney General in 2011. Olens’ political success is especially interesting considering he represents Marietta, the site of Leo Frank’s lynching in 1915.

Olens is part of large wave of Northern-born Jews who have transformed the Atlanta Jewish community over the last few decades. Jewish Atlanta has grown along with the city itself. The Atlanta metropolitan area grew from 726,789 people in 1950 to 4,247,981 in 2000. Atlanta remains one of the fastest growing cities in America, with its metro area growing 38% between 1990 and 2000. The Jewish community of Atlanta has grown at an even faster pace than the city itself. According to estimates in the American Jewish Year Book, Atlanta had 14,500 Jews in 1960 and 27,500 by 1980. Since then, the Jewish population has exploded, increasing over 300% to 86,000 in 2000. A population survey by the Atlanta Jewish Federation found that there were 120,000 Jews in the Atlanta metropolitan area in 2006.

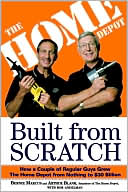

This growth has occurred due to Atlanta’s emergence as a corporate center. Atlanta’s position as a vital transportation hub, combined with the city’s temperate climate, has prompted many corporations to locate their headquarters in the city. Atlanta has grown from a regional to an international business center. This status is reflected in the rise of CNN as an international news organization and by the city’s hosting of the 1996 Summer Olympics. By the end of 2004, 700 of the “Fortune 1000” firms had offices in Atlanta. One of these was Home Depot, founded in 1978 in Marietta by New Jersey-born Bernie Marcus and native New Yorker Arthur Blank. Both Blank and Marcus have become important philanthropists in both the Jewish and larger community. Atlanta’s rise as a corporate center occurred as southern Jews entered the corporate world in larger numbers. While only 13% of working Atlanta Jews were professionals in 1946, by 1984, this figure had risen to 57%. The growth of Atlanta’s Jewish community and the decline of small town communities since World War II reflects the movement of southern Jews away from retail business ownership and toward corporate and professional occupations.

Olens is part of large wave of Northern-born Jews who have transformed the Atlanta Jewish community over the last few decades. Jewish Atlanta has grown along with the city itself. The Atlanta metropolitan area grew from 726,789 people in 1950 to 4,247,981 in 2000. Atlanta remains one of the fastest growing cities in America, with its metro area growing 38% between 1990 and 2000. The Jewish community of Atlanta has grown at an even faster pace than the city itself. According to estimates in the American Jewish Year Book, Atlanta had 14,500 Jews in 1960 and 27,500 by 1980. Since then, the Jewish population has exploded, increasing over 300% to 86,000 in 2000. A population survey by the Atlanta Jewish Federation found that there were 120,000 Jews in the Atlanta metropolitan area in 2006.

This growth has occurred due to Atlanta’s emergence as a corporate center. Atlanta’s position as a vital transportation hub, combined with the city’s temperate climate, has prompted many corporations to locate their headquarters in the city. Atlanta has grown from a regional to an international business center. This status is reflected in the rise of CNN as an international news organization and by the city’s hosting of the 1996 Summer Olympics. By the end of 2004, 700 of the “Fortune 1000” firms had offices in Atlanta. One of these was Home Depot, founded in 1978 in Marietta by New Jersey-born Bernie Marcus and native New Yorker Arthur Blank. Both Blank and Marcus have become important philanthropists in both the Jewish and larger community. Atlanta’s rise as a corporate center occurred as southern Jews entered the corporate world in larger numbers. While only 13% of working Atlanta Jews were professionals in 1946, by 1984, this figure had risen to 57%. The growth of Atlanta’s Jewish community and the decline of small town communities since World War II reflects the movement of southern Jews away from retail business ownership and toward corporate and professional occupations.

Arthur Blank & Bernie Marcus

Arthur Blank & Bernie Marcus

This amazing growth in the Atlanta Jewish community can be seen in the increasing number of Jewish congregations in the city. In 1947, there were six Jewish congregations in Atlanta. By 2004, there were 38 congregations in Metropolitan Atlanta. Of these 38, 33 were founded after 1968. These new congregations are concentrated in suburbs like Marietta, Dunwoody, and Alpharetta, where Jews are seeking places to worship close to home, a process influenced by Atlanta’s notorious traffic problems. This movement to the suburbs began as far back as 1946, when the local Jewish Welfare Board found that “the trend of [general] population is from the central area of the city towards the outskirts and the suburbs.” By 1984, 70% of Atlanta’s Jewish population lived outside of the city limits. In the late 1990s, the Jewish Community Center followed the city’s Jewish population, moving to the northern suburb of Dunwoody.