Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Augusta, Georgia

Historical Overview

|

Best known to many as the home of the Masters Golf Tournament, Augusta is the second oldest city in Georgia and boasts a history that goes back to the mid-18th century. James Oglethrope, the founder of the Georgia colony, created Augusta on the banks of the Savannah River in 1736. Originally a trading outpost, Augusta became the capital of the new state of Georgia from 1785 to 1795. The town began to boom with the arrival of cotton as a regional cash crop around the turn of the 19th century. Augusta became the commercial market for the expanding Georgia back country, as farmers shipped their crops to the growing town due to its location on the river. Augusta made an early transition to the railroad age when the town was linked to Charleston by rail in 1833; the 136-mile line is believed to have been the longest in the world at the time. The Augusta Canal, completed in 1845, harnessed the power of the river enabling Augusta to become an industrial center in the South. By the 1930s, Augusta had several textile mills and cottonseed oil factories in addition to a thriving brick industry based on the local red clay.

Just as Augusta’s history begins earlier than most other Southern towns, the same is true for its Jewish history. Jews arrived in Augusta in the early 19th century, starting a community that lasts today. |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Augusta

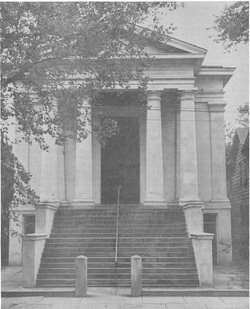

Children of Israel's first synagogue

Children of Israel's first synagogue

Early Settlers

The first recorded Jew in Augusta was Isaac Hendricks, who left Charleston and settled in the Georgia town in 1802 to trade with the Native Americans in the area. In the 1820s, Hendricks was joined by a handful of other Jews, including Isaac and Jacob Moise. Despite these early arrivals, an organized Jewish community didn’t develop in Augusta until the 1840s, when German immigrants began to arrive.

B'nai Israel

By 1845, there were five or six Jewish families in Augusta who banded together to form a religious school to teach their children about Judaism. Eleven children were in the school during its first year. A year later, the group formally founded Georgia’s second Jewish congregation, which they named “B’nai Israel” (Children of Israel). Its founding charter stated that the congregation was made up of “the scattered Israelites” of Augusta, Georgia, and Hamburg, South Carolina, which was located just across the river from Augusta. Its official purpose was communal worship and charity “toward our needy brethren.” Of the 20 charter members, about two-thirds came from Augusta and Hamburg, while the remainder came from surrounding towns. John J. Cohen was the first president of the congregation, which initially met in a rented room in Augusta. They later rented a building at the corner of 8th and Greene. Soon after the congregation was founded, the city gave them a plot of land in Magnolia Cemetery. Fittingly, the first person to be buried in this Jewish section was Isaac Hendricks.

In 1846, Jacob Moise reported on the success of the new congregation in the pages of the Occident, a Jewish newspaper edited by Rabbi Isaac Leeser in Philadelphia. Moise praised the work of the congregation, of which he was a member, crediting it with bolstering Judaism in Augusta. According to Moise, previously Jews in the area had mingled with Gentiles and “their identity as a religious sect has been entirely destroyed.” A later report from Moise proved the existence of intermarriage, as he detailed the circumcision of three young boys, aged 13, 10, and 9, who had been born to a Jewish mother and Christian father. The boys had been attending the Jewish religious school in Augusta and decided on their own to formally, if painfully, join the Jewish community. According to Moise, they endured the ceremony stoically, with one of the boys declaring afterward, “if God requires it, I will go through it again.”

B’nai Israel, though officially traditional in worship style, exhibited Reform tendencies from its founding. Their early services included some English prayers as well as a mixed-gender choir. They also began referring to the congregation by its English name, Children of Israel, rather than the Hebrew. But members still kept kosher, as evidenced by their advertising for a service leader (chazzan) and kosher butcher (shochet) in the Occident in 1851. The congregation hired Mr. Marcusson as their chazzan/shochet soon after. Isaac Leeser, an outspoken advocate for traditional Judaism, was no doubt lobbying the congregation to remain within the Orthodox fold when he came to speak in Augusta in 1852. Indeed, readers of Leeser’s Occident in Philadelphia donated money to the Augusta congregation in 1852 to help them purchase a Torah scroll.

Despite Leeser’s efforts and support, Children of Israel soon drifted toward the nascent movement of Reform Judaism. In 1869, when the congregation laid the cornerstone for its first synagogue, they brought down Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, the father of Reform Judaism in America, to give the keynote address. The synagogue had family pews for mixed-gender seating, a space for a choir, and an organ, clear evidence of its embrace of religious reform. When Rabbi Wise founded the Union of American Hebrew Congregations in 1873, Children of Israel was one of its first members.

The new synagogue, located on Telfair Street, cost $15,000 to build. For its dedication, there was a procession from their old rented building to the new synagogue. Members of the congregation led the parade, followed by the mayor and city council members, as well as members of the Masons and Odd Fellows lodge. By the time of the dedication in 1869, the largely immigrant membership of the congregation was well established in Augusta. Of the 44 members of Children of Israel, only 6% were native born. 75% were from Prussia while less than 10% were from Poland or Russia. Their average age was 41 years. The vast majority, 87%, were merchants, mostly in dry goods or clothing. Only one, a shoemaker, was a skilled laborer. According to the economic worth estimates included in the 1870 census, some members had managed to amass large fortunes through their business. Abraham Levy, a clothing merchant, owned $20,000 worth of real estate and $15,000 worth of personal estate in 1870. Others like Morris Harris, who only had $150 worth of personal estate, were of much more modest means. Despite these variations in members’ net worth, it is quite remarkable that almost 90% of members owned their own businesses.

The first recorded Jew in Augusta was Isaac Hendricks, who left Charleston and settled in the Georgia town in 1802 to trade with the Native Americans in the area. In the 1820s, Hendricks was joined by a handful of other Jews, including Isaac and Jacob Moise. Despite these early arrivals, an organized Jewish community didn’t develop in Augusta until the 1840s, when German immigrants began to arrive.

B'nai Israel

By 1845, there were five or six Jewish families in Augusta who banded together to form a religious school to teach their children about Judaism. Eleven children were in the school during its first year. A year later, the group formally founded Georgia’s second Jewish congregation, which they named “B’nai Israel” (Children of Israel). Its founding charter stated that the congregation was made up of “the scattered Israelites” of Augusta, Georgia, and Hamburg, South Carolina, which was located just across the river from Augusta. Its official purpose was communal worship and charity “toward our needy brethren.” Of the 20 charter members, about two-thirds came from Augusta and Hamburg, while the remainder came from surrounding towns. John J. Cohen was the first president of the congregation, which initially met in a rented room in Augusta. They later rented a building at the corner of 8th and Greene. Soon after the congregation was founded, the city gave them a plot of land in Magnolia Cemetery. Fittingly, the first person to be buried in this Jewish section was Isaac Hendricks.

In 1846, Jacob Moise reported on the success of the new congregation in the pages of the Occident, a Jewish newspaper edited by Rabbi Isaac Leeser in Philadelphia. Moise praised the work of the congregation, of which he was a member, crediting it with bolstering Judaism in Augusta. According to Moise, previously Jews in the area had mingled with Gentiles and “their identity as a religious sect has been entirely destroyed.” A later report from Moise proved the existence of intermarriage, as he detailed the circumcision of three young boys, aged 13, 10, and 9, who had been born to a Jewish mother and Christian father. The boys had been attending the Jewish religious school in Augusta and decided on their own to formally, if painfully, join the Jewish community. According to Moise, they endured the ceremony stoically, with one of the boys declaring afterward, “if God requires it, I will go through it again.”

B’nai Israel, though officially traditional in worship style, exhibited Reform tendencies from its founding. Their early services included some English prayers as well as a mixed-gender choir. They also began referring to the congregation by its English name, Children of Israel, rather than the Hebrew. But members still kept kosher, as evidenced by their advertising for a service leader (chazzan) and kosher butcher (shochet) in the Occident in 1851. The congregation hired Mr. Marcusson as their chazzan/shochet soon after. Isaac Leeser, an outspoken advocate for traditional Judaism, was no doubt lobbying the congregation to remain within the Orthodox fold when he came to speak in Augusta in 1852. Indeed, readers of Leeser’s Occident in Philadelphia donated money to the Augusta congregation in 1852 to help them purchase a Torah scroll.

Despite Leeser’s efforts and support, Children of Israel soon drifted toward the nascent movement of Reform Judaism. In 1869, when the congregation laid the cornerstone for its first synagogue, they brought down Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, the father of Reform Judaism in America, to give the keynote address. The synagogue had family pews for mixed-gender seating, a space for a choir, and an organ, clear evidence of its embrace of religious reform. When Rabbi Wise founded the Union of American Hebrew Congregations in 1873, Children of Israel was one of its first members.

The new synagogue, located on Telfair Street, cost $15,000 to build. For its dedication, there was a procession from their old rented building to the new synagogue. Members of the congregation led the parade, followed by the mayor and city council members, as well as members of the Masons and Odd Fellows lodge. By the time of the dedication in 1869, the largely immigrant membership of the congregation was well established in Augusta. Of the 44 members of Children of Israel, only 6% were native born. 75% were from Prussia while less than 10% were from Poland or Russia. Their average age was 41 years. The vast majority, 87%, were merchants, mostly in dry goods or clothing. Only one, a shoemaker, was a skilled laborer. According to the economic worth estimates included in the 1870 census, some members had managed to amass large fortunes through their business. Abraham Levy, a clothing merchant, owned $20,000 worth of real estate and $15,000 worth of personal estate in 1870. Others like Morris Harris, who only had $150 worth of personal estate, were of much more modest means. Despite these variations in members’ net worth, it is quite remarkable that almost 90% of members owned their own businesses.

Jewish Business in Augusta

Most Augusta Jews were concentrated in retail and wholesale trade. Joseph Meyers left Prussia in 1850 and soon started peddling in rural Georgia. He later opened a store in Crawfordville. After the Civil War, Meyers moved to Augusta, where he went into the wholesale dry goods business with another Jewish immigrant, Solomon Marcus. Meyers & Marcus became very successful, doing $1 million of business a year. Meyers was one of the only Jewish men in Augusta who kept his business closed on Saturdays, the Jewish Sabbath. As a wholesale firm, this was less of an economic sacrifice than it would be for a retail store owner, for whom Saturday was usually the busiest day of the week. Meyers was also very involved in local politics, serving two terms on the city council.

Prussian-born Simon Lesser became a cotton factor in Augusta, and was already worth $4000 by the time he was 22 years old. He came to own several cotton farms in the area and later served as a director of the National Exchange Bank. Other Jews were able to use their manual skills to became successful businessmen. David Slusky came to Augusta from Russia in 1881. In Russia, he had trained as a coppersmith, and first worked as a roofer when he got to Georgia. Eventually, Slusky bought $60 worth of tinner’s tools from Tom Watson, who would later go on to fame as a Populist leader and U.S. senator. In 1886, Slusky opened his own iron shop, which grew into a very successful business selling stoves, furnaces, galvanized iron, and cornices. Slusky’s metal work was used in buildings across the state. In 1891, he built a three-story building on Broad Street to house his business. His son Moses joined the firm in 1919, which later became a builders’ supply company. David Slusky was an important leader of the local Jewish community, serving as president of Children of Israel and co-founder of the Young Men’s Hebrew Association. Slusky was also the vice president of the Jewish Orphanage in Atlanta.

In addition to merchants and businessmen, several Augusta Jews were lawyers, and a few became local judges. Samuel Levy, who married Isaac Hendricks’ daughter and often led services for Children of Israel during their early years, was an elected judge in Augusta and also served on the city council. C. Henry Cohen served as the solicitor general of the superior court from 1877 to 1901. Isaac Levy, a South Carolina native, was Augusta’s sheriff for many years before his death in 1871. Louis Brooks and Samuel Meyers were also lawyers in the late 19th century, foreshadowing the rise of Jewish professionals in the South in the second half of the 20th century.

Most Augusta Jews were concentrated in retail and wholesale trade. Joseph Meyers left Prussia in 1850 and soon started peddling in rural Georgia. He later opened a store in Crawfordville. After the Civil War, Meyers moved to Augusta, where he went into the wholesale dry goods business with another Jewish immigrant, Solomon Marcus. Meyers & Marcus became very successful, doing $1 million of business a year. Meyers was one of the only Jewish men in Augusta who kept his business closed on Saturdays, the Jewish Sabbath. As a wholesale firm, this was less of an economic sacrifice than it would be for a retail store owner, for whom Saturday was usually the busiest day of the week. Meyers was also very involved in local politics, serving two terms on the city council.

Prussian-born Simon Lesser became a cotton factor in Augusta, and was already worth $4000 by the time he was 22 years old. He came to own several cotton farms in the area and later served as a director of the National Exchange Bank. Other Jews were able to use their manual skills to became successful businessmen. David Slusky came to Augusta from Russia in 1881. In Russia, he had trained as a coppersmith, and first worked as a roofer when he got to Georgia. Eventually, Slusky bought $60 worth of tinner’s tools from Tom Watson, who would later go on to fame as a Populist leader and U.S. senator. In 1886, Slusky opened his own iron shop, which grew into a very successful business selling stoves, furnaces, galvanized iron, and cornices. Slusky’s metal work was used in buildings across the state. In 1891, he built a three-story building on Broad Street to house his business. His son Moses joined the firm in 1919, which later became a builders’ supply company. David Slusky was an important leader of the local Jewish community, serving as president of Children of Israel and co-founder of the Young Men’s Hebrew Association. Slusky was also the vice president of the Jewish Orphanage in Atlanta.

In addition to merchants and businessmen, several Augusta Jews were lawyers, and a few became local judges. Samuel Levy, who married Isaac Hendricks’ daughter and often led services for Children of Israel during their early years, was an elected judge in Augusta and also served on the city council. C. Henry Cohen served as the solicitor general of the superior court from 1877 to 1901. Isaac Levy, a South Carolina native, was Augusta’s sheriff for many years before his death in 1871. Louis Brooks and Samuel Meyers were also lawyers in the late 19th century, foreshadowing the rise of Jewish professionals in the South in the second half of the 20th century.

Aaron Tanenbaum

Aaron Tanenbaum

Jewish Organizations in Augusta

In addition to the Children of Israel, Augusta Jews founded various other organizations in the late 19th century. In 1869, men founded a local chapter of the national Jewish fraternal society, B’nai B’rith. In 1879, women founded the Hebrew Ladies Aid Society, which later became the Sisterhood of Children of Israel. The society ran the congregation’s religious school, oversaw the choir, and managed the synagogue building. Simon Lesser’s wife Annie was one of the founders of the Ladies Aid Society and was later president of the local chapter of the Council of Jewish Women. In the late 19th century, Augusta Jews founded the Standard Club, an exclusively social institution. Its clubhouse featured a swimming pool and a billiard room.

Orthodox Jews in Augusta

The late 19th century also saw the arrival of growing numbers of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. A handful came from the town of Kobren, located in the Russian Pale. In 1889, five of these immigrant families in Augusta formed a small minyan in 1889 that met in Morris Steinberg’s apartment over his store. Steinberg had come to Augusta from Russia in 1886, when he was 23 years old. He became the leader of this small minyan, which adhered to Orthodox Judaism, in contrast to the Reform practices of Children of Israel. Soon, the group brought in a shochet, Abram Poliakoff, to supply them with kosher meat. The minyan grew quickly, reaching 100 Jews, many of whom were single men.

As the minyan grew, divisions developed over Jewish practices. Some of the members did not keep their stores closed on Saturdays, which upset other members of the minyan. In 1890, a disgruntled faction broke away to form a new minyan, which they called the “Keep Saturday Society.” Soon after, Jake Edelstein, who had been one of the original founders of the Orthodox minyan, broke away to form yet another group. In 1891, these three competing groups merged to form Congregation Adas Jeshurun. Jacob Tanenbaum was the first president of the congregation, which initially met in a building on Market Street. The Orthodox congregation grew quickly, and in 1895 it purchased land for a synagogue. Each of the 60 members pledged money to the building fund, and Adas Yeshurun soon built a modest synagogue for $1800, which included classrooms and a mikvah (Jewish ritual bath) in the basement.

In addition to the Children of Israel, Augusta Jews founded various other organizations in the late 19th century. In 1869, men founded a local chapter of the national Jewish fraternal society, B’nai B’rith. In 1879, women founded the Hebrew Ladies Aid Society, which later became the Sisterhood of Children of Israel. The society ran the congregation’s religious school, oversaw the choir, and managed the synagogue building. Simon Lesser’s wife Annie was one of the founders of the Ladies Aid Society and was later president of the local chapter of the Council of Jewish Women. In the late 19th century, Augusta Jews founded the Standard Club, an exclusively social institution. Its clubhouse featured a swimming pool and a billiard room.

Orthodox Jews in Augusta

The late 19th century also saw the arrival of growing numbers of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. A handful came from the town of Kobren, located in the Russian Pale. In 1889, five of these immigrant families in Augusta formed a small minyan in 1889 that met in Morris Steinberg’s apartment over his store. Steinberg had come to Augusta from Russia in 1886, when he was 23 years old. He became the leader of this small minyan, which adhered to Orthodox Judaism, in contrast to the Reform practices of Children of Israel. Soon, the group brought in a shochet, Abram Poliakoff, to supply them with kosher meat. The minyan grew quickly, reaching 100 Jews, many of whom were single men.

As the minyan grew, divisions developed over Jewish practices. Some of the members did not keep their stores closed on Saturdays, which upset other members of the minyan. In 1890, a disgruntled faction broke away to form a new minyan, which they called the “Keep Saturday Society.” Soon after, Jake Edelstein, who had been one of the original founders of the Orthodox minyan, broke away to form yet another group. In 1891, these three competing groups merged to form Congregation Adas Jeshurun. Jacob Tanenbaum was the first president of the congregation, which initially met in a building on Market Street. The Orthodox congregation grew quickly, and in 1895 it purchased land for a synagogue. Each of the 60 members pledged money to the building fund, and Adas Yeshurun soon built a modest synagogue for $1800, which included classrooms and a mikvah (Jewish ritual bath) in the basement.

Despite their new home, Augusta’s Orthodox Jews had not quelled all of their divisions. In 1902, Adas Yeshurun split over a dispute regarding the shochet. When the congregation hired a new kosher butcher, the old shochet, Abram Poliakoff led a breakaway group that prayed together on Reynolds Street. After three years, the two groups reunited as Adas Yeshurun and employed both shochets. Both butchers were kept busy as Augusta’s population of Orthodox Jewish immigrants continued to grow. By 1907, about 500 Jews lived in the city. The Orthodox Adas Yeshurun had 65 member households while the Reform Children of Israel had only 42. In 1909, the women of Adas Yeshurun founded the Daughters of Israel, which raised charity for needy Jews. Later, the group focused their charitable efforts on the synagogue and Hebrew School. By 1915, Adas Yeshurun had outgrown its synagogue, and purchased a former church on Ellis Street to use as their new home. True to their Orthodox practices, the old church was outfitted with a balcony for female worshipers and a mikvah.

Over the years, the members of Adas Yeshurun made some cultural accommodations and religious innovations while remaining true to Orthodox Judaism. In 1930, the board, most of whom had been raised in the United States, voted to change the language of the annual meetings and minutes from Yiddish to English. Also, members were no longer satisfied with a chazzan/shochet as service leader, and hired their first ordained rabbi, Henry Goldberger, in 1944. Rabbi Goldberger introduced some changes, including a Friday night service, a mixed-gender confirmation class, and a Sunday morning minyan club for post-bar mitzvah boys. Despite these innovations, the congregation remained committed to Orthodox Judaism, which was explicitly written into their 1949 constitution. According to this constitution, “the Rabbi must be an ordained Orthodox Rabbi.” The congregation continued to hold minyans twice daily and still employed a shochet.

Among the Orthodox shul’s leaders was Aaron Tanenbaum, who became one of the foremost Zionists in the South. Sixteen-year-old Tanenbaum left Poland for the United States in 1889 to join his father Jacob, who had settled in Augusta after peddling for two years in Georgia. Aaron peddled as well during his first two years in Georgia, after which he and his father had saved enough money to bring over the rest of the family from Poland. Aaron had been a Yeshiva student in Poland before he left. While studying Talmud was a far cry from peddling in rural Georgia, Aaron continued his studies informally. Tanenbaum was an early ardent Zionist, forming Augusta’s Lovers of Zion, the first Zionist organization in the Southeast, around the turn of the century. In 1901, Tanenbaum traveled as a delegate to the World Zionist Congress in London. Over the years, he attended several other Zionist conventions. Tanenbaum was unwilling to compromise his religious practices, and decided to buy a dairy farm so he could more easily observe the Jewish Sabbath and other rituals. By 1907, Augusta had two Zionist societies: the Lovers of Zion and the Daughters of Zion. There was also a chapter of the Jewish Socialist-Territorialist Labor Party in Augusta, one of only two in the entire South at the time.

Over the years, the members of Adas Yeshurun made some cultural accommodations and religious innovations while remaining true to Orthodox Judaism. In 1930, the board, most of whom had been raised in the United States, voted to change the language of the annual meetings and minutes from Yiddish to English. Also, members were no longer satisfied with a chazzan/shochet as service leader, and hired their first ordained rabbi, Henry Goldberger, in 1944. Rabbi Goldberger introduced some changes, including a Friday night service, a mixed-gender confirmation class, and a Sunday morning minyan club for post-bar mitzvah boys. Despite these innovations, the congregation remained committed to Orthodox Judaism, which was explicitly written into their 1949 constitution. According to this constitution, “the Rabbi must be an ordained Orthodox Rabbi.” The congregation continued to hold minyans twice daily and still employed a shochet.

Among the Orthodox shul’s leaders was Aaron Tanenbaum, who became one of the foremost Zionists in the South. Sixteen-year-old Tanenbaum left Poland for the United States in 1889 to join his father Jacob, who had settled in Augusta after peddling for two years in Georgia. Aaron peddled as well during his first two years in Georgia, after which he and his father had saved enough money to bring over the rest of the family from Poland. Aaron had been a Yeshiva student in Poland before he left. While studying Talmud was a far cry from peddling in rural Georgia, Aaron continued his studies informally. Tanenbaum was an early ardent Zionist, forming Augusta’s Lovers of Zion, the first Zionist organization in the Southeast, around the turn of the century. In 1901, Tanenbaum traveled as a delegate to the World Zionist Congress in London. Over the years, he attended several other Zionist conventions. Tanenbaum was unwilling to compromise his religious practices, and decided to buy a dairy farm so he could more easily observe the Jewish Sabbath and other rituals. By 1907, Augusta had two Zionist societies: the Lovers of Zion and the Daughters of Zion. There was also a chapter of the Jewish Socialist-Territorialist Labor Party in Augusta, one of only two in the entire South at the time.

Rabbi Sylvan Schwartzman

Rabbi Sylvan Schwartzman

The Early 20th Century

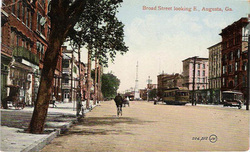

While Tanenbaum worked as a dairy farmer, most other Augusta Jews remained concentrated in commercial trade. Jewish-owned stores lined Broad Street in downtown Augusta. Brothers Jake and Charles Schneider owned a large department store in the first half of the 20th century. In 1894, Henry Simowitz and his large family left Hungary for the United States. After spending several years in Cincinnati, the family moved to Augusta, where Henry opened a clothing store. Henry and his wife Annie had eleven children; of their six sons, five remained in Augusta and owned a variety of businesses. Sam and Joe Simowitz opened the S&J Shoe Store; their younger brother Bernard later became a partner in the business. Harry Simowitz owned the Augusta Trading Company, while Louis owned a store that sold electric victrolas.

The YMHA

Although Augusta’s Jewish community remained divided into two different congregations, they came together in 1935 to create the Young Men’s Hebrew Association (YMHA). The founding meeting was held at Adas Yeshurun, though members of Children of Israel played a crucial role in its founding and success. One of these leaders was Nathan Jolles, a local attorney who had served as president of Adas Yeshurun and vice president of Children of Israel. In 1935, the YMHA dedicated its first building on Greene Street, which became a social center and meeting place for the entire Augusta Jewish community in addition to offering athletic and theatrical programs. Augusta Mayor Richard Allen took part in the building dedication. During World War II, the YMHA building was used as a USO club for Jewish soldiers stationed at nearby Camp Gordon. In the 1950s, the YMHA moved to a new property on Sibley Road and became known as the Jewish Community Center. In 1998 the JCC built a new facility on Weinberger Way.

While Tanenbaum worked as a dairy farmer, most other Augusta Jews remained concentrated in commercial trade. Jewish-owned stores lined Broad Street in downtown Augusta. Brothers Jake and Charles Schneider owned a large department store in the first half of the 20th century. In 1894, Henry Simowitz and his large family left Hungary for the United States. After spending several years in Cincinnati, the family moved to Augusta, where Henry opened a clothing store. Henry and his wife Annie had eleven children; of their six sons, five remained in Augusta and owned a variety of businesses. Sam and Joe Simowitz opened the S&J Shoe Store; their younger brother Bernard later became a partner in the business. Harry Simowitz owned the Augusta Trading Company, while Louis owned a store that sold electric victrolas.

The YMHA

Although Augusta’s Jewish community remained divided into two different congregations, they came together in 1935 to create the Young Men’s Hebrew Association (YMHA). The founding meeting was held at Adas Yeshurun, though members of Children of Israel played a crucial role in its founding and success. One of these leaders was Nathan Jolles, a local attorney who had served as president of Adas Yeshurun and vice president of Children of Israel. In 1935, the YMHA dedicated its first building on Greene Street, which became a social center and meeting place for the entire Augusta Jewish community in addition to offering athletic and theatrical programs. Augusta Mayor Richard Allen took part in the building dedication. During World War II, the YMHA building was used as a USO club for Jewish soldiers stationed at nearby Camp Gordon. In the 1950s, the YMHA moved to a new property on Sibley Road and became known as the Jewish Community Center. In 1998 the JCC built a new facility on Weinberger Way.

Children of Israel. Photo courtesy of

Julian Preisler

Children of Israel. Photo courtesy of

Julian Preisler

Augusta Congregations the 20th Century

Throughout its history, Children of Israel has had numerous rabbis, with most only staying a few years. For one-third of its first 100 years, the congregation did not have rabbinic leadership; during the other 67 years, they employed 25 different rabbis. A few stayed several years: Rabbi H. Cert Strauss led the congregation from 1920 to 1927, while Joseph Leiser served as rabbi from 1930 to 1939. In 1941, a young Hebrew Union College graduate, Sylvan Schwartzman, took over the pulpit at Children of Israel. Although he only stayed for six years, Rabbi Schwartzman had a profound impact on the congregation. When he arrived, Children of Israel had only approximately 60 member families. Five years later, it had 105 families. Rabbi Schwartzman brought a new energy to the congregation, leading a popular adult education class and starting a regular interfaith community forum. During the war, he led services at the local military base. Rabbi Schwartzman was not afraid to push the congregation to take political stands. In 1945, the congregation sent a letter to the US Secretary of State urging his support for the plan to create a United Nations. Rabbi Schwartzman also raised money for the Haganah, the group fighting for Jewish independence in Palestine.

Rabbi Schwartzman also led the way in convincing the congregation that it needed a new building, which could no longer hold its growing number of families. At Children of Israel’s centennial celebration in 1945, members voted to build a new synagogue. In 1946, they appointed a building committee, headed by Mose Slusky, that acquired a lot on the corner of Walton Way and Bransford Road. While it took several more years to raise the necessary money, Children of Israel finally dedicated its new synagogue in 1951. Rabbi Sylvan Schwartzman, who had left Augusta in 1947, came back to give the dedication address. Reverend J. Hambry Barton of the Trinity on the Hill Methodist Church gave the invocation during the ceremony. For the six months before they moved into their new home, the congregation had met at Rev. Barton’s church. According to the local newspaper, “the symbols of both religions remained on the same altar during this entire period in a perfect example of religious brotherhood.”

Rabbi Norman Goldburg arrived in 1949 and led the congregation for the next 19 years before becoming rabbi emeritus. Under Rabbi Goldburg’s leadership, Children of Israel continued to grow, reaching 142 families by 1955. By 1963, the congregation had 103 children in its religious school, which was run by the rabbi’s wife Rose Goldburg. By 1964, Children of Israel had outgrown its sanctuary, and members voted to build a new one along with a new kitchen and social hall, just 13 years after they had dedicated their current synagogue. Abe Friedman, a longtime board member of the congregation who served several terms as president, headed the effort to raise money for the addition. The local First Baptist Church made a donation to the building fund. In 1967, they dedicated the new sanctuary in a ceremony that drew Augusta’s mayor and several local ministers and featured the theme of interfaith harmony. The old sanctuary was converted into an auditorium for the religious school. Children of Israel thrived in their revamped building. By 1976, the congregation had 161 member families and 61 children in its religious school. By the mid 1990s, Augusta’s Reform congregation had reached 197 member families.

Throughout its history, Children of Israel has had numerous rabbis, with most only staying a few years. For one-third of its first 100 years, the congregation did not have rabbinic leadership; during the other 67 years, they employed 25 different rabbis. A few stayed several years: Rabbi H. Cert Strauss led the congregation from 1920 to 1927, while Joseph Leiser served as rabbi from 1930 to 1939. In 1941, a young Hebrew Union College graduate, Sylvan Schwartzman, took over the pulpit at Children of Israel. Although he only stayed for six years, Rabbi Schwartzman had a profound impact on the congregation. When he arrived, Children of Israel had only approximately 60 member families. Five years later, it had 105 families. Rabbi Schwartzman brought a new energy to the congregation, leading a popular adult education class and starting a regular interfaith community forum. During the war, he led services at the local military base. Rabbi Schwartzman was not afraid to push the congregation to take political stands. In 1945, the congregation sent a letter to the US Secretary of State urging his support for the plan to create a United Nations. Rabbi Schwartzman also raised money for the Haganah, the group fighting for Jewish independence in Palestine.

Rabbi Schwartzman also led the way in convincing the congregation that it needed a new building, which could no longer hold its growing number of families. At Children of Israel’s centennial celebration in 1945, members voted to build a new synagogue. In 1946, they appointed a building committee, headed by Mose Slusky, that acquired a lot on the corner of Walton Way and Bransford Road. While it took several more years to raise the necessary money, Children of Israel finally dedicated its new synagogue in 1951. Rabbi Sylvan Schwartzman, who had left Augusta in 1947, came back to give the dedication address. Reverend J. Hambry Barton of the Trinity on the Hill Methodist Church gave the invocation during the ceremony. For the six months before they moved into their new home, the congregation had met at Rev. Barton’s church. According to the local newspaper, “the symbols of both religions remained on the same altar during this entire period in a perfect example of religious brotherhood.”

Rabbi Norman Goldburg arrived in 1949 and led the congregation for the next 19 years before becoming rabbi emeritus. Under Rabbi Goldburg’s leadership, Children of Israel continued to grow, reaching 142 families by 1955. By 1963, the congregation had 103 children in its religious school, which was run by the rabbi’s wife Rose Goldburg. By 1964, Children of Israel had outgrown its sanctuary, and members voted to build a new one along with a new kitchen and social hall, just 13 years after they had dedicated their current synagogue. Abe Friedman, a longtime board member of the congregation who served several terms as president, headed the effort to raise money for the addition. The local First Baptist Church made a donation to the building fund. In 1967, they dedicated the new sanctuary in a ceremony that drew Augusta’s mayor and several local ministers and featured the theme of interfaith harmony. The old sanctuary was converted into an auditorium for the religious school. Children of Israel thrived in their revamped building. By 1976, the congregation had 161 member families and 61 children in its religious school. By the mid 1990s, Augusta’s Reform congregation had reached 197 member families.

Adas Yeshurun. Photo courtesy of

Julian Preisler

Adas Yeshurun. Photo courtesy of

Julian Preisler

Adas Yeshurun grew over the years as well. In 1944, members decided they had outgrown their old and deteriorating building. Led by William Estroff, the congregation quickly raised $70,000 for the building fund. But soon this effort stalled after the deaths of both Estroff and Rabbi Goldberger along with growing disagreement over where to build the new synagogue. While Adas Yeshurun had always been in downtown Augusta, the vast majority of members now lived in the Hill neighborhood. While most wanted to build it there, a strong faction lobbied to keep the shul downtown. Adas Yeshurun found a creative if untenable way to bridge this divide. One member, Pincus Silver, bought a big house and property on Johns Road, which was converted into a satellite site of the congregation. Separate High Holiday services were held at the Johns Road house with a visiting rabbi for those who preferred the residential location over the downtown synagogue. The Johns Road house even had an optional “family seating” section where husbands and wives could sit together if they wished.

Maintaining two synagogues was not a viable long-term solution, and Silver soon sold the Johns Road property to the congregation, which had finally decided to move from its old building. In 1953, they broke ground on a new synagogue on the property, finishing it the following year. At the time of the dedication, Adas Yeshurun had 200 member families. Despite this move, Adas Yeshurun remained an Orthodox congregation, building a new modern mikvah in the late 1960s. When Adas Yeshurun celebrated its 75th anniversary in 1965, the rabbi from the Orthodox Baron Hirsch Congregation in Memphis took part in the ceremony. In 1970, Adas Yeshurun dedicated a new education building; Senator Herman Talmadge was the keynote speaker at the dedication.

As reflected in the steady growth of both congregations, Augusta’s Jewish community peaked in the years after World War II. While 950 Jews lived in Augusta in 1937, 1500 did by 1980. As the number of Jewish merchants has declined, as it has throughout the rest of the South, growing numbers of Jewish professionals have settled in Augusta. Dr. Robert Greenblatt moved to Augusta in the 1930s and became a renowned endocrinologist, writing several books on the subject. Dr. Sumner Fishbein came to Augusta by the 1970s, and became very active at Children of Israel, serving on the board, teaching religious school, and blowing shofar on the High Holidays. With this rising number of professionals, Augusta managed to avoid the sharp population declines that affected other Southern Jewish communities.

Maintaining two synagogues was not a viable long-term solution, and Silver soon sold the Johns Road property to the congregation, which had finally decided to move from its old building. In 1953, they broke ground on a new synagogue on the property, finishing it the following year. At the time of the dedication, Adas Yeshurun had 200 member families. Despite this move, Adas Yeshurun remained an Orthodox congregation, building a new modern mikvah in the late 1960s. When Adas Yeshurun celebrated its 75th anniversary in 1965, the rabbi from the Orthodox Baron Hirsch Congregation in Memphis took part in the ceremony. In 1970, Adas Yeshurun dedicated a new education building; Senator Herman Talmadge was the keynote speaker at the dedication.

As reflected in the steady growth of both congregations, Augusta’s Jewish community peaked in the years after World War II. While 950 Jews lived in Augusta in 1937, 1500 did by 1980. As the number of Jewish merchants has declined, as it has throughout the rest of the South, growing numbers of Jewish professionals have settled in Augusta. Dr. Robert Greenblatt moved to Augusta in the 1930s and became a renowned endocrinologist, writing several books on the subject. Dr. Sumner Fishbein came to Augusta by the 1970s, and became very active at Children of Israel, serving on the board, teaching religious school, and blowing shofar on the High Holidays. With this rising number of professionals, Augusta managed to avoid the sharp population declines that affected other Southern Jewish communities.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Augusta Today

The former JCC in Augusta

The former JCC in Augusta

The Jewish community of Augusta did decrease in size at the end of the 20th century, declining to 1,300 people in 2003. As of 2021, Augusta still supports two active congregations with full-time rabbis and a local Jewish Federation. Some local Jews also attend services in nearby Aiken, South Carolina. In 1995, Adas Yeshurun officially became a Conservative congregation, joining the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism. Seeing an opportunity to serve Orthodox Jews, Chabad opened a house in Augusta in 1996. In recent years, as the number of children in the community has declined, the two congregations have merged their religious schools, creating the Augusta Jewish Community Sunday School. It had 45 students in 2009. That same year, Children of Israel had 157 members while Adas Yeshurun had 170.

Two notable changes took place in the Augusta Jewish community in 2021. First, the Augusta Jewish Community Center (AJCC) downsized and sold the large complex that had opened in 1998. In 2022 the AJCC merged with the Augusta Jewish Federation to form the Jewish Community Center and Federation of Augusta, which serves the Augusta-Aiken area. Second, the Augusta Jewish Museum opened in an 1860 county court building, adjacent to the original Children of Israel building—the oldest standing synagogue in Georgia. The city had planned to demolish both structures in 2015, but an alliance of community groups fought to save the buildings. The renovated courthouse opened in summer 2021 and includes an exhibit on local Jewish history. As of 2022, an anticipated renovation of the synagogue will transform it into an event space. While the original synagogue building serves as a testament to the Augusta Jewish community’s long history, local Jews’ involvement in its preservation and rehabilitation demonstrate their ongoing importance in the broader community.

Two notable changes took place in the Augusta Jewish community in 2021. First, the Augusta Jewish Community Center (AJCC) downsized and sold the large complex that had opened in 1998. In 2022 the AJCC merged with the Augusta Jewish Federation to form the Jewish Community Center and Federation of Augusta, which serves the Augusta-Aiken area. Second, the Augusta Jewish Museum opened in an 1860 county court building, adjacent to the original Children of Israel building—the oldest standing synagogue in Georgia. The city had planned to demolish both structures in 2015, but an alliance of community groups fought to save the buildings. The renovated courthouse opened in summer 2021 and includes an exhibit on local Jewish history. As of 2022, an anticipated renovation of the synagogue will transform it into an event space. While the original synagogue building serves as a testament to the Augusta Jewish community’s long history, local Jews’ involvement in its preservation and rehabilitation demonstrate their ongoing importance in the broader community.