Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Dalton, Georgia

Dalton: Historical Overview

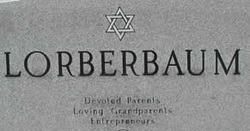

In the Blue Ridge Mountains of northwest Georgia is a Jewish cemetery overlooking the misty hills of Appalachia. In the back of the graveyard, one finds the shared gravestone of Alan and Shirley Lorberbaum, “Devoted parents, loving grandparents and entrepreneurs.” It may seem strange to place a term like “entrepreneur” on a tombstone, but it is not surprising that a Jewish resident would find pride in being forever remembered as “entrepreneur” in Dalton, the “carpet capital of the world.” Today, Dalton and surrounding areas produce 90% of the functional carpet worldwide. Jewish Daltonians played a crucial role in making the town a prominent industrial center in the United States. Their presence has left a permanent imprint on the commercial, cultural, and social character of the Dalton community.

The area that became Dalton was first inhabited by Creek Indians. The Cherokees displaced them in the mid-18th century, only to be forced west in 1838 under President Andrew Jackson’s removal policy. By 1847, settlement by white Americans led to the establishment of the township of Dalton, named by New York merchant Edward White after his maternal grandfather, Senator Tristam Dalton of Massachusetts. The same year the village gained its name, it also witnessed a development that would have crucial importance in years to come: the Western and Atlantic Railroad. Connecting the town to Chattanooga, Tennessee in 1850, the Western and Atlantic Railroad, in addition to being the first rail system west of Appalachia, ended Dalton’s economic seclusion that was characteristic of many mountain communities in the US Southeast. In 1851, Dalton was named the government seat of Whitfield County, marking its commercial significance in northwest Georgia.

On the eve of the Civil War, Dalton, like many hilly areas of the South that did not rely on cotton and slavery, was a pro-Union enclave. This did not spare it from the destruction of Sherman’s March.

Antebellum Dalton had few if any Jews to speak of. Though more commercially open and successful than towns like it, Dalton was still emblematic of what historian Douglas Flamming called “hilly upcountry,” marked by “its self-sufficient yeoman farmers and its economic isolation.” Unlike many areas of the antebellum South that grew tremendously wealthy from slavery and cotton production, the prominent business of antebellum Dalton was Prater’s Mill, which offered “various milling services, a wool carder, cotton gin, a general store and a blacksmith shop.” The relative simplicity of Dalton’s emerging market activity may have been an insufficient pull for immigrant Jews that were beginning to settle in the South during the mid-19th century. It was only with the advent of the industrial New South that a Jewish presence developed in Dalton.

The area that became Dalton was first inhabited by Creek Indians. The Cherokees displaced them in the mid-18th century, only to be forced west in 1838 under President Andrew Jackson’s removal policy. By 1847, settlement by white Americans led to the establishment of the township of Dalton, named by New York merchant Edward White after his maternal grandfather, Senator Tristam Dalton of Massachusetts. The same year the village gained its name, it also witnessed a development that would have crucial importance in years to come: the Western and Atlantic Railroad. Connecting the town to Chattanooga, Tennessee in 1850, the Western and Atlantic Railroad, in addition to being the first rail system west of Appalachia, ended Dalton’s economic seclusion that was characteristic of many mountain communities in the US Southeast. In 1851, Dalton was named the government seat of Whitfield County, marking its commercial significance in northwest Georgia.

On the eve of the Civil War, Dalton, like many hilly areas of the South that did not rely on cotton and slavery, was a pro-Union enclave. This did not spare it from the destruction of Sherman’s March.

Antebellum Dalton had few if any Jews to speak of. Though more commercially open and successful than towns like it, Dalton was still emblematic of what historian Douglas Flamming called “hilly upcountry,” marked by “its self-sufficient yeoman farmers and its economic isolation.” Unlike many areas of the antebellum South that grew tremendously wealthy from slavery and cotton production, the prominent business of antebellum Dalton was Prater’s Mill, which offered “various milling services, a wool carder, cotton gin, a general store and a blacksmith shop.” The relative simplicity of Dalton’s emerging market activity may have been an insufficient pull for immigrant Jews that were beginning to settle in the South during the mid-19th century. It was only with the advent of the industrial New South that a Jewish presence developed in Dalton.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Dalton

Early Jewish Settlers

The roots of Dalton’s Jewish community were nourished by the fertile commercial and industrial potential of the town in the late 19th century. According to Flamming, “nothing so clearly dominated the landscape of the post-Civil War South as the region’s cotton textile mills.” As imposing visual markers of the New South, their rise mirrored that of the Jewish population in Dalton. The first recorded Jewish settler in the town arrived in 1880, a florist named Mr. Hirsch. In 1884, the Crown Cotton Mill opened in Dalton, the first large-scale manufacturing plant in northwest Georgia. As Dalton underwent industrialization, the original Jewish settlers became established in the community. D.R. Loveman (originally Liebman) emigrated from Hungary in the late 19th century, operating a clothing store in Dalton. One of his four children, Robert Loveman became a famous poet, writing his most famous poem, “The Rain Song,” in 1899. Another of his compositions, “Georgia,” was the state’s official song until 1979. Ivan Millender, a current Daltonian, writes that the original Jewish residents enjoyed mercantile success and middle class comfort.

The roots of Dalton’s Jewish community were nourished by the fertile commercial and industrial potential of the town in the late 19th century. According to Flamming, “nothing so clearly dominated the landscape of the post-Civil War South as the region’s cotton textile mills.” As imposing visual markers of the New South, their rise mirrored that of the Jewish population in Dalton. The first recorded Jewish settler in the town arrived in 1880, a florist named Mr. Hirsch. In 1884, the Crown Cotton Mill opened in Dalton, the first large-scale manufacturing plant in northwest Georgia. As Dalton underwent industrialization, the original Jewish settlers became established in the community. D.R. Loveman (originally Liebman) emigrated from Hungary in the late 19th century, operating a clothing store in Dalton. One of his four children, Robert Loveman became a famous poet, writing his most famous poem, “The Rain Song,” in 1899. Another of his compositions, “Georgia,” was the state’s official song until 1979. Ivan Millender, a current Daltonian, writes that the original Jewish residents enjoyed mercantile success and middle class comfort.

The Bedspread Industry

The bedspread industry was the first to take off. A native of Dalton, Catherine Evans Whitener popularized a tufting technique known as “candlewick embroidery” in the beginning of the 20th century. She and other women of Dalton would sell their bedspreads along U.S. Highway 41, which ran between Copper Harbor, Michigan, and Miami, Florida, a parkway dubbed “bedspread” or “chenille alley.” The introduction of automobiles to the highway gave birth to a successful bedspread cottage industry in Dalton. As demand grew, Whitener and her brother began the Evans Manufacturing Company. The emergence of widespread manufacturing employment proved a watershed for Dalton, altering the social composition of the town and attracted the small city’s prominent Jewish families.

As the bedspread industry became established, the population of both Dalton and its Jewish community grew significantly. In 1930, there were six Jewish families in Dalton; by the 1960s, there were between 50 and 60. Many of the Jewish arrivals were entrepreneurs. Sam Millender opened the clothing store Millender’s. Several merchants arrived from Chattanooga, such as the Stock, Dubrof, Koplan, Morris, and Solomon families. Others came from Atlanta, like the Tenenbaums, the Levin/Bravers, the Sauls, the Mendels, the Franks, and the Golds. Abe Tenenbaum operated a retail store, while Jack Braver ran Braver’s Department Store. A survey of the city directories through the middle decades of the 20th century reveals an entrepreneurial spirit among the Jewish population, sustained by the manufacturing base of Dalton.

The bedspread industry was the first to take off. A native of Dalton, Catherine Evans Whitener popularized a tufting technique known as “candlewick embroidery” in the beginning of the 20th century. She and other women of Dalton would sell their bedspreads along U.S. Highway 41, which ran between Copper Harbor, Michigan, and Miami, Florida, a parkway dubbed “bedspread” or “chenille alley.” The introduction of automobiles to the highway gave birth to a successful bedspread cottage industry in Dalton. As demand grew, Whitener and her brother began the Evans Manufacturing Company. The emergence of widespread manufacturing employment proved a watershed for Dalton, altering the social composition of the town and attracted the small city’s prominent Jewish families.

As the bedspread industry became established, the population of both Dalton and its Jewish community grew significantly. In 1930, there were six Jewish families in Dalton; by the 1960s, there were between 50 and 60. Many of the Jewish arrivals were entrepreneurs. Sam Millender opened the clothing store Millender’s. Several merchants arrived from Chattanooga, such as the Stock, Dubrof, Koplan, Morris, and Solomon families. Others came from Atlanta, like the Tenenbaums, the Levin/Bravers, the Sauls, the Mendels, the Franks, and the Golds. Abe Tenenbaum operated a retail store, while Jack Braver ran Braver’s Department Store. A survey of the city directories through the middle decades of the 20th century reveals an entrepreneurial spirit among the Jewish population, sustained by the manufacturing base of Dalton.

Temple Beth El

Temple Beth El

Organized Jewish Life in Dalton

The industrial boom of Dalton made it ripe for a flourishing Jewish community to emerge. By 1937, the Jewish population of 40 residents formed the origin of a future congregation. A year later, several prominent Jews of Dalton formed the “Friendly Alliance,” organized to host minyans and High Holiday services in the Loveman Library. This first Jewish organization in Dalton history soon pushed for the construction of a Jewish house of worship in the town. In May of 1941 at a meeting in Simon Mendel’s Café, the preliminary president of the congregation, Sam Hurowitz, was joined by other elected officers as the organization came up with a platform to establish a synagogue. The council vowed to establish a constitution for a congregation, secure a rabbi for services, and explore the possibility of purchasing land to construct a synagogue. Shortly after, a Sisterhood was formed in the home of Mrs. Ella Hurowitz and duly undertook measures to aid in the construction of the temple. A vote of the Jewish community in Dalton was taken on June 24th, 1941, unanimously approving the construction of a synagogue; a month later, a constitution was ratified for Temple Beth El.

World War II

The formation of a Jewish congregation coincided with the US entry into World War II. The war was a crucial event in world Jewry, notably for the reason that America became the epicenter of Jewish civilization following the extermination of much of European Jewish life. In many ways, Dalton illustrated this “Golden Age” of Jews in the United States. The establishment of Temple Beth El in Dalton exemplifies the ways in which Jews became fully assimilated into American life. In the middle of construction of the temple, the War Production Board froze civilian purchase of building materials. The founders of the temple agreed to shift construction funds to purchase War Bonds and aid the war effort. The Sisterhood of Temple Beth El also sacrificed, donating medical supplies, canned goods, and money from fundraisers to various charities helping those affected by the war’s dislocations, as well as purchasing War Bonds. These charitable activities served as a precursor to future organizations such as The Dalton Jewish Welfare Fund, which became the Dalton United Jewish Appeal. These developments were not only formative experiences for the Dalton Jewish community but evidence that Jews had become interwoven into the fabric of mainstream American life.

After World War II

The post-World War II economic boom immensely benefited Dalton’s factories. Beginning in the 1940s, the manufacturing techniques used for bedspread production were reoriented towards a host of new consumer products, such as carpets and chenille rugs and robes. The subsequent economic and demographic expansion spurred the arrival of new Jewish residents, many from New York and outside the US. In fact, as Flamming argues, “this industrial expansion was led in large part by a small but economically influential Jewish community the members of which had migrated to Dalton from the northeast.” Thus Jewish settlement became integrally tied to the fundamental manufacturing character of Dalton.

A prime example is Ira Nochumson, a businessman from Chicago who became a respected commercial leader in the community. Arriving around the time of the carpet boom in the 1950s, Nochumson became president of the Tufted Textile Manufacturers’ Association, an organization designed to lobby for chenille and carpet interests. Though this new crop of Jewish management was met with a degree of reservation from the established business leaders of thoroughly Southern ancestry, these “non-Protestant Yankees” worked to assimilate themselves into the local culture. Nochumson became a leader in the Elks, the Masons, the Lions Club and the Community Chest. By 1953, when Nochumson was elected president of the Tufted Textile Manufacturer’s Association, a local paper described the new head as “a member of the Jewish families of Dalton [who] has done much not only for his nationality, but for all groups in the county.” Nochumson was one of several Jews who gained local prominence in the town’s manufacturing base. Jerry Gold, owner of Gold and Company Manufacturers of Rugs and Bath Mat Sets, became another important business leader in Dalton. As Flamming states, “many Chenille manufacturers were still Dalton natives, but Nochumson and his fellow Jewish industrialists, such as Harry Saul and Arthur Richman, represented a new line of business leaders in Dalton, and their presence reflected the tentative beginnings of a more diverse and fluid southern society.”

The industrial boom of Dalton made it ripe for a flourishing Jewish community to emerge. By 1937, the Jewish population of 40 residents formed the origin of a future congregation. A year later, several prominent Jews of Dalton formed the “Friendly Alliance,” organized to host minyans and High Holiday services in the Loveman Library. This first Jewish organization in Dalton history soon pushed for the construction of a Jewish house of worship in the town. In May of 1941 at a meeting in Simon Mendel’s Café, the preliminary president of the congregation, Sam Hurowitz, was joined by other elected officers as the organization came up with a platform to establish a synagogue. The council vowed to establish a constitution for a congregation, secure a rabbi for services, and explore the possibility of purchasing land to construct a synagogue. Shortly after, a Sisterhood was formed in the home of Mrs. Ella Hurowitz and duly undertook measures to aid in the construction of the temple. A vote of the Jewish community in Dalton was taken on June 24th, 1941, unanimously approving the construction of a synagogue; a month later, a constitution was ratified for Temple Beth El.

World War II

The formation of a Jewish congregation coincided with the US entry into World War II. The war was a crucial event in world Jewry, notably for the reason that America became the epicenter of Jewish civilization following the extermination of much of European Jewish life. In many ways, Dalton illustrated this “Golden Age” of Jews in the United States. The establishment of Temple Beth El in Dalton exemplifies the ways in which Jews became fully assimilated into American life. In the middle of construction of the temple, the War Production Board froze civilian purchase of building materials. The founders of the temple agreed to shift construction funds to purchase War Bonds and aid the war effort. The Sisterhood of Temple Beth El also sacrificed, donating medical supplies, canned goods, and money from fundraisers to various charities helping those affected by the war’s dislocations, as well as purchasing War Bonds. These charitable activities served as a precursor to future organizations such as The Dalton Jewish Welfare Fund, which became the Dalton United Jewish Appeal. These developments were not only formative experiences for the Dalton Jewish community but evidence that Jews had become interwoven into the fabric of mainstream American life.

After World War II

The post-World War II economic boom immensely benefited Dalton’s factories. Beginning in the 1940s, the manufacturing techniques used for bedspread production were reoriented towards a host of new consumer products, such as carpets and chenille rugs and robes. The subsequent economic and demographic expansion spurred the arrival of new Jewish residents, many from New York and outside the US. In fact, as Flamming argues, “this industrial expansion was led in large part by a small but economically influential Jewish community the members of which had migrated to Dalton from the northeast.” Thus Jewish settlement became integrally tied to the fundamental manufacturing character of Dalton.

A prime example is Ira Nochumson, a businessman from Chicago who became a respected commercial leader in the community. Arriving around the time of the carpet boom in the 1950s, Nochumson became president of the Tufted Textile Manufacturers’ Association, an organization designed to lobby for chenille and carpet interests. Though this new crop of Jewish management was met with a degree of reservation from the established business leaders of thoroughly Southern ancestry, these “non-Protestant Yankees” worked to assimilate themselves into the local culture. Nochumson became a leader in the Elks, the Masons, the Lions Club and the Community Chest. By 1953, when Nochumson was elected president of the Tufted Textile Manufacturer’s Association, a local paper described the new head as “a member of the Jewish families of Dalton [who] has done much not only for his nationality, but for all groups in the county.” Nochumson was one of several Jews who gained local prominence in the town’s manufacturing base. Jerry Gold, owner of Gold and Company Manufacturers of Rugs and Bath Mat Sets, became another important business leader in Dalton. As Flamming states, “many Chenille manufacturers were still Dalton natives, but Nochumson and his fellow Jewish industrialists, such as Harry Saul and Arthur Richman, represented a new line of business leaders in Dalton, and their presence reflected the tentative beginnings of a more diverse and fluid southern society.”

Beth El Celebrates its 40th anniversary in 1980.

Beth El Celebrates its 40th anniversary in 1980.

Temple Beth El

Following the War, construction of the Temple Beth El synagogue continued. Progress on the building encountered several problems, namely acquiring supplies during the post-war material shortages, flooding, and unforeseen expenses that led to a second mortgage. In the end, building Temple Beth El cost between $80,000 and $90,000, a testament to the resolve of Dalton’s Jews to establish a temple for themselves and their children. On March 9th, 1947, Temple Beth El was formally dedicated in a public ceremony.

The synagogue has been a Conservative congregation since its inception. In large part, this reflects the background of many of its founding members who did not originate from the South but grew up in Jewish enclaves of large cities, such Ira Nochumson from Chicago, Gerald Spiegel from London, and others. In 1962, Temple Beth El became affiliated with the United Synagogue of America, an association of Conservative congregations. The synagogue has had a host of rabbis who have conducted Sunday school along with laypeople of the congregation, notable Francine Lumiere. In 1950, the temple had its first bar mitzvah, Lewis Millender, and in 1953 its first wedding, that of Myra Stein and Harold Shapiro. In 1956, a plot was purchased which became the Dalton Cemetery’s Jewish burial ground. By the 1960s, the Sunday school enjoyed regular attendance from the Jewish children of Dalton and the congregation reached a height of 63 families. In the 1980s, the female members of the synagogue successfully lobbied to have gender equality at all levels of congregational activity and later the first female president, Ellen Richman, was elected to head the temple. Over these decades, the congregation thrived and even welcomed new Jewish families. In 1990, Temple Beth El celebrated its 50th anniversary, receiving dedications from the mayor of Dalton, Georgia Governor Joe Frank Harris, US Senator Wyche Fowler and even President George H.W. Bush.

Following the War, construction of the Temple Beth El synagogue continued. Progress on the building encountered several problems, namely acquiring supplies during the post-war material shortages, flooding, and unforeseen expenses that led to a second mortgage. In the end, building Temple Beth El cost between $80,000 and $90,000, a testament to the resolve of Dalton’s Jews to establish a temple for themselves and their children. On March 9th, 1947, Temple Beth El was formally dedicated in a public ceremony.

The synagogue has been a Conservative congregation since its inception. In large part, this reflects the background of many of its founding members who did not originate from the South but grew up in Jewish enclaves of large cities, such Ira Nochumson from Chicago, Gerald Spiegel from London, and others. In 1962, Temple Beth El became affiliated with the United Synagogue of America, an association of Conservative congregations. The synagogue has had a host of rabbis who have conducted Sunday school along with laypeople of the congregation, notable Francine Lumiere. In 1950, the temple had its first bar mitzvah, Lewis Millender, and in 1953 its first wedding, that of Myra Stein and Harold Shapiro. In 1956, a plot was purchased which became the Dalton Cemetery’s Jewish burial ground. By the 1960s, the Sunday school enjoyed regular attendance from the Jewish children of Dalton and the congregation reached a height of 63 families. In the 1980s, the female members of the synagogue successfully lobbied to have gender equality at all levels of congregational activity and later the first female president, Ellen Richman, was elected to head the temple. Over these decades, the congregation thrived and even welcomed new Jewish families. In 1990, Temple Beth El celebrated its 50th anniversary, receiving dedications from the mayor of Dalton, Georgia Governor Joe Frank Harris, US Senator Wyche Fowler and even President George H.W. Bush.

However, this period proved to be the summit before the Jewish community began its demographic decline. Beginning in the 1980s, many of the original congregants and temple leaders passed away, including Mr. and Mrs. Ben Winkler and four past presidents – Leo Koplan, Sam Millender, Joseph Ginsberg, and Lester Goldberg. Throughout the 1990s, elderly members retired and many moved to Florida. While the older population disappeared, younger Jews who grew up in Dalton went off to college and did not return. Julian Saul, whose father Harry Saul was one of the founders of Temple Beth El, mentions how his sons went off to universities and have relocated to major cities, one working for Senator Orrin Hatch in Washington D.C. and the other working for the William Morris Talent Agency in Los Angeles. Much of this population decline is a product of transitions in Dalton’s economy. Large retailers such as Wal-Mart have overtaken local markets as small retailers traditionally owned by Jewish businessmen have merged, gone public, or closed.

The Jewish Community in Dalton Today

The longevity of Temple Beth El was sustained by the fact that many Jews in Dalton did not work as store owners but as managers in the local manufacturing industry. The recent Southern-wide shift of Jews into professional careers as well as to large metropolitan areas with higher density Jewish populations has not left Dalton unscathed. The religious school as of 2008 had only a handful of pupils and the congregants of Temple Beth El are considering selling their synagogue.

However, Mr. Saul says that he and the rest of the Jewish community of Dalton will follow the advice of Allan Finkel, a former congregation officer and for many years “the real backbone” of Temple Beth El, to “keep the doors open ‘til the last person leaves.” Such sentiment is understandable considering the lovely edifice that is Temple Beth El. The striking exterior is matched by the beauty of its interior, with its stained-glass windows, mahogany seats, and the artwork that decorates the basement of the synagogue. The building is a worthy testament to the dedication of the Jewish community, both past and present, and its immense contribution to the commercial and spiritual development of Dalton.

However, Mr. Saul says that he and the rest of the Jewish community of Dalton will follow the advice of Allan Finkel, a former congregation officer and for many years “the real backbone” of Temple Beth El, to “keep the doors open ‘til the last person leaves.” Such sentiment is understandable considering the lovely edifice that is Temple Beth El. The striking exterior is matched by the beauty of its interior, with its stained-glass windows, mahogany seats, and the artwork that decorates the basement of the synagogue. The building is a worthy testament to the dedication of the Jewish community, both past and present, and its immense contribution to the commercial and spiritual development of Dalton.