Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Fitzgerald, Georgia

Fitzgerald: Historical Overview

As you drive through downtown Fitzgerald, you might notice something strange. Along with street names honoring Confederate heroes like Robert E. Lee and James Longstreet, one also finds streets honoring Ulysses S. Grant and even the bete noire of the Southern lost cause, William Tecumseh Sherman. Touted as the “City where American Reunited,” Fitzgerald was founded in 1896 as a colony for Civil War veterans of both sides by Philander Fitzgerald, a newspaper editor from Indianapolis. Georgia’s governor wanted to settle Georgia’s sparsely populated wiregrass region and backed Fitzgerald’s colonization plan. The town soon grew, and became the seat of the new Ben Hill County in 1906. Along with the streets named for heroes of both sides of the war, the local grand hotel was named the “Lee-Grant.” Fitzgerald was also home to regular unity parades in which both Union and Confederate veterans would march together through downtown.

If Fitzgerald helped to unite North and South, its Jewish community and congregation tied together a Jewish population spread throughout the small towns of south central Georgia. Jews came to the area relatively late, in the early years of the 20th century. The community remains today.

If Fitzgerald helped to unite North and South, its Jewish community and congregation tied together a Jewish population spread throughout the small towns of south central Georgia. Jews came to the area relatively late, in the early years of the 20th century. The community remains today.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Fitzgerald

The Big Store in Tifton

The Big Store in Tifton

Early Settlers

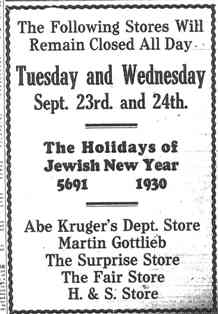

One of the first Jews to settle in town was Isadore Goldenberg, who came to the United States from Romania in 1888. By 1900, he was living in Fitzgerald with his new bride Bessie and owned a dry goods store. By 1910, Goldenberg had two other Jewish immigrants as partners, Joseph Kassewitz and Sam Abram. Abram was also from Romania and lived with Goldenberg as a boarder. A handful of other Jewish immigrants lived in Fitzgerald at the time; most were in the dry goods business. In 1910, they held services for Yom Kippur at a local hall. According to the Fitzgerald newspaper, the town’s Jewish-owned stores were all closed for the religious holiday. Jewish immigrants continued to settle in the area. In 1920, the Russian-born Harry Garber lived in Fitzgerald and owned a dry goods business called the Surprise Store. His wife Sadie, who had been born in New York, worked in the store with her husband and took care of four Jewish boarders who lived with them. The Garbers opened another branch of their store in Thomasville in 1920. Jake Tatel, who came from Russia in 1909, eventually settled in Fitzgerald, where he opened the Farmers’ Dry Goods Company. Abe Kruger, who would go on to be a longtime leader of the local Jewish community, came to the U.S. in 1911 from Russia and by 1920 owned a dry goods store in Fitzgerald.

Jewish immigrants also settled in the small towns around Fitzgerald. Abraham Harris, who was born in Odessa, Russia, came to Oscilla, Georgia, in 1906, and opened a store that became the town’s largest retail emporium. Ike Perlis came over from Russia with his family and opened a dry goods store in Cordele, Georgia. His son Isadore eventually took over the business. Isadore and his sons built a chain of clothing stores around the area, including the Big Store in Tifton, run by Marvin and Lynette Perlis. The Perlis brothers later branched out into real estate development. Today, Marvin and Lynette’s son, Philip Perlis, and his wife Susan run the store in Tifton, marking the fourth generation of south Georgia retail merchants in the Perlis family. Other Jews owned stores in the Georgia towns of Nashville, Dublin, Hawkinsville, Alamo, and Eastman.

One of the first Jews to settle in town was Isadore Goldenberg, who came to the United States from Romania in 1888. By 1900, he was living in Fitzgerald with his new bride Bessie and owned a dry goods store. By 1910, Goldenberg had two other Jewish immigrants as partners, Joseph Kassewitz and Sam Abram. Abram was also from Romania and lived with Goldenberg as a boarder. A handful of other Jewish immigrants lived in Fitzgerald at the time; most were in the dry goods business. In 1910, they held services for Yom Kippur at a local hall. According to the Fitzgerald newspaper, the town’s Jewish-owned stores were all closed for the religious holiday. Jewish immigrants continued to settle in the area. In 1920, the Russian-born Harry Garber lived in Fitzgerald and owned a dry goods business called the Surprise Store. His wife Sadie, who had been born in New York, worked in the store with her husband and took care of four Jewish boarders who lived with them. The Garbers opened another branch of their store in Thomasville in 1920. Jake Tatel, who came from Russia in 1909, eventually settled in Fitzgerald, where he opened the Farmers’ Dry Goods Company. Abe Kruger, who would go on to be a longtime leader of the local Jewish community, came to the U.S. in 1911 from Russia and by 1920 owned a dry goods store in Fitzgerald.

Jewish immigrants also settled in the small towns around Fitzgerald. Abraham Harris, who was born in Odessa, Russia, came to Oscilla, Georgia, in 1906, and opened a store that became the town’s largest retail emporium. Ike Perlis came over from Russia with his family and opened a dry goods store in Cordele, Georgia. His son Isadore eventually took over the business. Isadore and his sons built a chain of clothing stores around the area, including the Big Store in Tifton, run by Marvin and Lynette Perlis. The Perlis brothers later branched out into real estate development. Today, Marvin and Lynette’s son, Philip Perlis, and his wife Susan run the store in Tifton, marking the fourth generation of south Georgia retail merchants in the Perlis family. Other Jews owned stores in the Georgia towns of Nashville, Dublin, Hawkinsville, Alamo, and Eastman.

Though they had not yet formed a congregation,

Though they had not yet formed a congregation, Fitzgerald Jews observed the high holidays in 1930

The Great Depression and the Hebrew Commercial Alliance

Though they had not yet formed a congregation, Fitzgerald Jews observed the High Holidays in 1930.

Facing a credit crunch during the early years of the Great Depression, these Jewish store owners banded together in 1929 to form the Hebrew Commercial Alliance. Using the combined financial leverage of its members, the Alliance secured capital from local banks, and lent the money to Jewish businesses that did not have the cash on hand to pay their suppliers. Starting with just 18 members and $7,500, the Fitzgerald-based Alliance had 75 members from 15 different south Georgia counties by 1932. At their annual meeting in 1935, the Alliance’s president, Phillip Halperin, a Fitzgerald merchant, reported that it had 147 members, some in neighboring states, and $77,500 in capital. The previous year, the Alliance had made loans totaling $347,000, all of which were paid back. The Alliance soon set up a wholesale operation, which supplied dry goods to its members from a warehouse in Fitzgerald. By 1953, the Alliance was loaning out almost $1 million a year to its members. This was not a free loan society; interest rates could be steep. Jewish merchants usually turned to the Alliance as a last resort. The organization continued into the 1960s, although it eventually disbanded since so many Jewish owned stores had gone out of business.

Although the Hebrew Commercial Alliance was an economic organization, it had a strong Jewish identity. It was only open to Jewish merchants and helped to support an area Jewish Sunday school and later the Fitzgerald Jewish Congregation. In 1948, the group ended its annual meeting with the singing of the Zionist anthem “Hatikvah” and bought Israel bonds to support the fledgling Jewish state.

Jewish Industrialists

While the Hebrew Commercial Alliance focused on retail stores, especially dry goods, Jews in and around Fitzgerald played a leading role in the area’s industrial growth. South Georgia became a regional center for the garment industry as northern companies headed south in search of cheaper labor costs. Many Southern towns offered economic incentives to these companies to relocate their operations. In 1936, the New York-based Lucky Strike Silk Stocking Company, headed by Arthur Hirsch, moved its mill to Fitzgerald after the city offered them a free building and a five-year tax exemption. H.R. “Dick” Kaminsky came to Georgia from Brooklyn, opening the Perfect Pants Manufacturing Company in Ashburn in 1934. Two years later, he moved the business to Fitzgerald, and eventually changed its name to H.R. Kaminsky & Sons, Inc., which made pants for men and boys. Over the years, Kaminsky’s business grew from only a few employees to almost 650 when they doubled the size of their plant in 1963. Over the years, the business has shrunk somewhat, but still had 255 employees and three factories as late as 1988. H.R. Kaminsky & Sons is still in business today. Other Jewish industrialists included Max Heller, who started in Fitzgerald as a dry goods merchant before opening a children’s clothing manufacturing business in Oscilla.

Though they had not yet formed a congregation, Fitzgerald Jews observed the High Holidays in 1930.

Facing a credit crunch during the early years of the Great Depression, these Jewish store owners banded together in 1929 to form the Hebrew Commercial Alliance. Using the combined financial leverage of its members, the Alliance secured capital from local banks, and lent the money to Jewish businesses that did not have the cash on hand to pay their suppliers. Starting with just 18 members and $7,500, the Fitzgerald-based Alliance had 75 members from 15 different south Georgia counties by 1932. At their annual meeting in 1935, the Alliance’s president, Phillip Halperin, a Fitzgerald merchant, reported that it had 147 members, some in neighboring states, and $77,500 in capital. The previous year, the Alliance had made loans totaling $347,000, all of which were paid back. The Alliance soon set up a wholesale operation, which supplied dry goods to its members from a warehouse in Fitzgerald. By 1953, the Alliance was loaning out almost $1 million a year to its members. This was not a free loan society; interest rates could be steep. Jewish merchants usually turned to the Alliance as a last resort. The organization continued into the 1960s, although it eventually disbanded since so many Jewish owned stores had gone out of business.

Although the Hebrew Commercial Alliance was an economic organization, it had a strong Jewish identity. It was only open to Jewish merchants and helped to support an area Jewish Sunday school and later the Fitzgerald Jewish Congregation. In 1948, the group ended its annual meeting with the singing of the Zionist anthem “Hatikvah” and bought Israel bonds to support the fledgling Jewish state.

Jewish Industrialists

While the Hebrew Commercial Alliance focused on retail stores, especially dry goods, Jews in and around Fitzgerald played a leading role in the area’s industrial growth. South Georgia became a regional center for the garment industry as northern companies headed south in search of cheaper labor costs. Many Southern towns offered economic incentives to these companies to relocate their operations. In 1936, the New York-based Lucky Strike Silk Stocking Company, headed by Arthur Hirsch, moved its mill to Fitzgerald after the city offered them a free building and a five-year tax exemption. H.R. “Dick” Kaminsky came to Georgia from Brooklyn, opening the Perfect Pants Manufacturing Company in Ashburn in 1934. Two years later, he moved the business to Fitzgerald, and eventually changed its name to H.R. Kaminsky & Sons, Inc., which made pants for men and boys. Over the years, Kaminsky’s business grew from only a few employees to almost 650 when they doubled the size of their plant in 1963. Over the years, the business has shrunk somewhat, but still had 255 employees and three factories as late as 1988. H.R. Kaminsky & Sons is still in business today. Other Jewish industrialists included Max Heller, who started in Fitzgerald as a dry goods merchant before opening a children’s clothing manufacturing business in Oscilla.

The Fitzgerald Hebrew Congregation

In 1947, the Fitzgerald Hebrew Congregation hired its first full-time rabbi, Nathan Kohen. Despite his Orthodox training, Rabbi Kohen introduced some religious innovations, including the confirmation ritual. The Fitzgerald Hebrew Congregation was essentially Conservative, rather than Orthodox; they would only hold Shabbat services on Friday nights since so many members had to work in their stores on Saturday mornings. Kohen was very involved in the larger community, and often spoke to groups like the Rotary & Kiwanis Clubs in area towns. His wife Bea ran the congregation’s religious school and would stage elaborate annual Hannukah Programs, with songs and dramatic scenes acted out by the children. In 1954, the congregation added an education annex to their building. Rabbi Kohen served the Fitzgerald Hebrew Congregation for 28 years, until his death in 1975. He remains the only full-time rabbi ever to serve the congregation.

The Fitzgerald synagogue was the center of a truly regional congregation. In 1968, the congregation’s 14 board members came from 10 different towns. In the early 1950s, they held auxiliary, lay-led services on Friday nights in Dublin, which was 75 miles away. By 1956, they had opened a branch of the religious school in Tifton with 12 students; Rabbi Kohen would lead the classes on Tuesday evenings.

The congregation’s newsletter in the 1950s and 1960s was like a small-town newspaper, with lots of social news about its members. Congregants could learn who was traveling where, who was sick, as well as the various accomplishments of the members and their children. The long social news column, put together by the rebbitzen Bea Kohen, helped to bind together this dispersed group into one community.

In 1947, the Fitzgerald Hebrew Congregation hired its first full-time rabbi, Nathan Kohen. Despite his Orthodox training, Rabbi Kohen introduced some religious innovations, including the confirmation ritual. The Fitzgerald Hebrew Congregation was essentially Conservative, rather than Orthodox; they would only hold Shabbat services on Friday nights since so many members had to work in their stores on Saturday mornings. Kohen was very involved in the larger community, and often spoke to groups like the Rotary & Kiwanis Clubs in area towns. His wife Bea ran the congregation’s religious school and would stage elaborate annual Hannukah Programs, with songs and dramatic scenes acted out by the children. In 1954, the congregation added an education annex to their building. Rabbi Kohen served the Fitzgerald Hebrew Congregation for 28 years, until his death in 1975. He remains the only full-time rabbi ever to serve the congregation.

The Fitzgerald synagogue was the center of a truly regional congregation. In 1968, the congregation’s 14 board members came from 10 different towns. In the early 1950s, they held auxiliary, lay-led services on Friday nights in Dublin, which was 75 miles away. By 1956, they had opened a branch of the religious school in Tifton with 12 students; Rabbi Kohen would lead the classes on Tuesday evenings.

The congregation’s newsletter in the 1950s and 1960s was like a small-town newspaper, with lots of social news about its members. Congregants could learn who was traveling where, who was sick, as well as the various accomplishments of the members and their children. The long social news column, put together by the rebbitzen Bea Kohen, helped to bind together this dispersed group into one community.

Molly Picon with members of the Fitzgerald Hebrew Congregation

Molly Picon with members of the Fitzgerald Hebrew Congregation

Special events also brought the congregation together. In 1953, famed Yiddish actress Molly Picon came to Fitzgerald to help raise money for the state of Israel. Three years later, actor Zero Mostel headlined an Israel Bonds gala that raised over $30,000 for the fledgling Jewish state. The Hebrew Commercial Alliance purchased $4000 worth of bonds. The Sisterhood also helped to unite the congregation. The group held monthly programs with guest speakers and helped to run the religious school. Today, the Sisterhood members oversee the synagogue’s kosher kitchen and send out the congregation’s monthly newsletter.

Civic Engagement

Jews in Fitzgerald and its surrounding towns were deeply engaged in civic affairs. Fitzgerald merchant Martin Gottlieb left the city a large bequest that was to be used to purchase Christmas gifts for needy children. In Fitzgerald, it was said that Santa Claus was Jewish! In addition to leading the local Jewish congregation, Abe Kruger was also a leader in local government. After he sold his dry goods store to the Belk chain in 1954, he decided to turn his attention to local politics. As he wrote in his first campaign ad for city council, “since I am no longer actively engaged in business, I am going to make the progress of Fitzgerald my business if I am elected.” Despite his Yiddish accent, Kruger served many years on the Fitzgerald City Council; for several years he was mayor pro tem as a result of being the top vote-getter among all city council candidates. When he ran for re-election in 1964, he won over 80% of the vote. Kruger did not try to hide his Jewishness in his campaign ads, which mentioned his longtime leadership of the Fitzgerald Hebrew Congregation. Kruger also served as a director of the local chamber of commerce and headed the local Red Cross chapter.

Civic Engagement

Jews in Fitzgerald and its surrounding towns were deeply engaged in civic affairs. Fitzgerald merchant Martin Gottlieb left the city a large bequest that was to be used to purchase Christmas gifts for needy children. In Fitzgerald, it was said that Santa Claus was Jewish! In addition to leading the local Jewish congregation, Abe Kruger was also a leader in local government. After he sold his dry goods store to the Belk chain in 1954, he decided to turn his attention to local politics. As he wrote in his first campaign ad for city council, “since I am no longer actively engaged in business, I am going to make the progress of Fitzgerald my business if I am elected.” Despite his Yiddish accent, Kruger served many years on the Fitzgerald City Council; for several years he was mayor pro tem as a result of being the top vote-getter among all city council candidates. When he ran for re-election in 1964, he won over 80% of the vote. Kruger did not try to hide his Jewishness in his campaign ads, which mentioned his longtime leadership of the Fitzgerald Hebrew Congregation. Kruger also served as a director of the local chamber of commerce and headed the local Red Cross chapter.

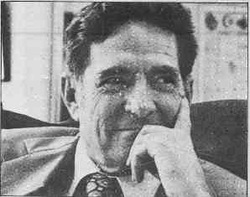

Morris Abram

Morris Abram

Perhaps the most notable civic leader to come from Fitzgerald was Morris Abram, who became an influential American legal and political figure as well as a national Jewish leader. The son of merchant Sam Abram, Morris was born in Fitzgerald in 1918. After serving in World War II and winning a Rhodes Scholarship, Abram became a lawyer in Atlanta. Abram challenged the state’s “county unit rule,” which gave each county the same political weight despite their population. He eventually took the case to the U.S. Supreme Court which threw out the county unit rule in 1963, establishing the constitutional principle of “one man, one vote.” Abram was later appointed to be the US representative to the United Nations Commission on Human Rights and served as general counsel to the Peace Corps. Abram was also the longtime chairman of the United Negro College Fund, and served as president of Brandeis University for a few years. Abram became a leader of the national Jewish community, serving as president of the American Jewish Committee and the Conference of Presidents of Major Jewish American Organizations.

The Jewish Community in Fitzgerald Today

According to the American Jewish Year Book, in 1937 about 250 Jews lived in the small towns in and around Fitzgerald. By the 1960s, these small Jewish communities were shrinking as the retail business changed and young people moved to larger cities in search of greater opportunity. Jewish-owned stores, which once lined Grant and Pine streets in downtown Fitzgerald, began to close. Today, there are no Jewish-owned stores in Fitzgerald. The Big Store in Tifton, now run by Philip and Susan Perlis, remains one of the last vestiges of the Jewish-owned stores that were once omnipresent in the small towns of south Georgia.

Despite this decline in the number of Jews, the Fitzgerald Hebrew Congregation remains active. Since the death of Rabbi Kohen in 1975, the congregation has brought in student rabbis from the Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary in New York. The small numbers of remaining members are close-knit; they usually have dinner together once a month in conjunction with Friday night services. The congregation remains in close contact with those families and children who have moved away. In 1992, they had a large 50th anniversary homecoming event. On Rosh Hashanah, many of the people who were raised in Fitzgerald but moved away to places like Atlanta, come back for services. The congregation can draw as many as 150 people for Rosh Hashanah services.

Despite this decline in the number of Jews, the Fitzgerald Hebrew Congregation remains active. Since the death of Rabbi Kohen in 1975, the congregation has brought in student rabbis from the Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary in New York. The small numbers of remaining members are close-knit; they usually have dinner together once a month in conjunction with Friday night services. The congregation remains in close contact with those families and children who have moved away. In 1992, they had a large 50th anniversary homecoming event. On Rosh Hashanah, many of the people who were raised in Fitzgerald but moved away to places like Atlanta, come back for services. The congregation can draw as many as 150 people for Rosh Hashanah services.