Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Rome, Georgia

Rome: Historical Overview

|

Rome, Georgia, sits in the southern foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. Indeed, it was Rome’s seven hills that served as the inspiration for the town’s name, when the town’s founders likened its topography to the historic city in Italy. This connection was strengthened in 1929 when Italy’s leader, Benito Mussolini, donated a replica of Rome’s famous statue of Romulus and Remus nursing from a wolf to the Georgia town.

Rome was originally in the heart of Cherokee territory. After the forced removal of the tribe, white settlers began to arrive. The city was officially founded in 1834 at the spot where the Etowah and Oostanaula Rivers converge into the Coosa River. It was Rome’s location on the river that led to its initial development as a cotton trading town. It was soon linked by rail to larger cities in the region. After the Civil War, Rome became a regional industrial center, with metal stove factories and textile mills moving to the area. Jews have been part of the city's history since the 19th century. |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Rome

Early Settlers

It’s unclear when the first Jews came to Rome. According to some local Jewish histories, a man named Mordecai Myers lived in Rome in 1833, and a O.A. Myers owned a newspaper in town in 1850, but there is no evidence that these men were Jewish. By the time of the Civil War, a handful of Jews had settled in Rome, including Joseph J. Cohen, a native of Bremen, who owned a store on Broad Street in the 1850s. Cohen achieved rather quick success, owning $4000 in real estate by 1860. He also had $30,000 in personal property, including six slaves. Cohen was not the only Jewish slave owner in Rome. Morris Marks was a Prussian immigrant who had settled in Rome in the years before the Civil War. By 1860, he was a successful merchant and owned two slaves. According to the historian Bertram Korn, Southern Jews were just as likely to own slaves as non-Jews who lived in cities in the antebellum South. Since both Marks and Cohen owned retail businesses, their slaves were most likely household servants. In 1870, both men had black servants living with their families.

The Civil War

During the Civil War, Rome Jews identified with the Southern cause. Several fought for the Confederacy, including the Prussian-born Philip Cohen, who was a successful 29-year-old merchant when the war broke out. Jewish women in Rome became active in the local Ladies Aid Society, which made clothes and blankets for the Southern soldiers. Rachel Cohen, Jacob’s wife, and Susan Marks, Morris’ wife, were among the Jewish members of the society, which also nursed sick and wounded soldiers. Another member of the Rome Jewish community, a Dr. Fox, was in charge of Rome’s first hospital which was built during the war to treat the wounded. Rome’s Jewish community suffered from General William Tecumseh Sherman’s occupation of the city, as several of their businesses were burned by the Northern army. David Meyerhardt who owned a storehouse on Broad Street, saw it destroyed in the fires that engulfed the downtown district.

It’s unclear when the first Jews came to Rome. According to some local Jewish histories, a man named Mordecai Myers lived in Rome in 1833, and a O.A. Myers owned a newspaper in town in 1850, but there is no evidence that these men were Jewish. By the time of the Civil War, a handful of Jews had settled in Rome, including Joseph J. Cohen, a native of Bremen, who owned a store on Broad Street in the 1850s. Cohen achieved rather quick success, owning $4000 in real estate by 1860. He also had $30,000 in personal property, including six slaves. Cohen was not the only Jewish slave owner in Rome. Morris Marks was a Prussian immigrant who had settled in Rome in the years before the Civil War. By 1860, he was a successful merchant and owned two slaves. According to the historian Bertram Korn, Southern Jews were just as likely to own slaves as non-Jews who lived in cities in the antebellum South. Since both Marks and Cohen owned retail businesses, their slaves were most likely household servants. In 1870, both men had black servants living with their families.

The Civil War

During the Civil War, Rome Jews identified with the Southern cause. Several fought for the Confederacy, including the Prussian-born Philip Cohen, who was a successful 29-year-old merchant when the war broke out. Jewish women in Rome became active in the local Ladies Aid Society, which made clothes and blankets for the Southern soldiers. Rachel Cohen, Jacob’s wife, and Susan Marks, Morris’ wife, were among the Jewish members of the society, which also nursed sick and wounded soldiers. Another member of the Rome Jewish community, a Dr. Fox, was in charge of Rome’s first hospital which was built during the war to treat the wounded. Rome’s Jewish community suffered from General William Tecumseh Sherman’s occupation of the city, as several of their businesses were burned by the Northern army. David Meyerhardt who owned a storehouse on Broad Street, saw it destroyed in the fires that engulfed the downtown district.

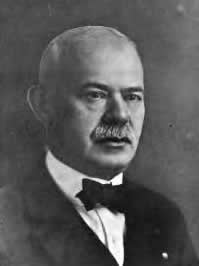

Issac May

Issac May

After the Civil War

Like Rome itself, the city’s Jewish community rose from these ashes after the war. By 1870, Jacob Cohen, Morris Marks, and David Meyerhardt were still flourishing merchants in Rome; in fact, the value of their real estate holdings had increased significantly during the turbulent decade. After the war, Rome’s Jewish population grew. Prussian-born Jacob Kuttner moved to Rome from New York in 1871, opening a dry goods store. Kuttner’s sons, Max and Sam, took over the business after he died in 1905. Jacob Kuttner’s daughter Hilda married a young Alsatian immigrant named Isaac May, who had come to Rome in the early 1880s from Muncie, Indiana, where he had worked as a store clerk. May became a longtime dry goods merchant in Rome and a leading member of the local Jewish community.

Rodeph Sholom

In 1875, the growing number of Jews in Rome, led by David Meyerhardt, organized a congregation, Rodeph Sholom. Its name, which means “Pursuers of Peace,” was certainly salient in a region still working to recover from the Civil War and Reconstruction. Soon after, Jacob Cohen donated land to the congregation on Mount Aventine for use as a cemetery. Initially, the group met in private homes, though by 1890 they were meeting on the second floor of the local Masonic Temple, which remained the congregations home for the next 50 years. The congregation founded a religious school which also met at the Masonic Temple. The congregation was led by the same family for its first 60 years. Philip Cohen was the first president of Rodeph Shalom, serving for ten years. He was succeeded in 1885 by his brother-in-law, Jacob Kuttner, who led the congregation until his death in 1905. Kuttner’s son-in-law, Isaac May, then took over the reins, serving as president until 1938.

The Early 20th Century

In the early 20th century, an influx of Jewish immigrants from the Russian empire began to arrive in Rome. Jacob Mendelson left Russia in 1896, and settled in Rome by 1905, where he opened a dry goods store. Two brothers, Pressley and Joe Esserman, left Russia in 1891; by 1896, they had settled in Rome and opened Esserman’s Store, which remained in business for almost a century. According to family lore, Pressley learned English by going to the local Baptist Church, where he heard them read the Old Testament, which he could translate into Hebrew. After a few years in business in Rome, the brothers were able to bring over the rest of their family, including their parents, David and Lena Esserman, and four younger brothers in 1898. Initially, the entire family lived together above the store on Broad Street.

This wave of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe pushed Rome’s Jewish community from 104 Jews in 1907 to a peak of 250 Jews in 1919. Most of these were concentrated in retail trade, and Jewish-owned businesses lined the streets of Rome’s downtown. The community was made up of large families; in 1922, almost 60 children were in the Rodeph Sholom religious school.

David Esserman was a rabbi by training, and became the spiritual leader of Rodeph Sholom until his death in 1917. He brought a Torah with him to Rome that was used by the congregation. Rodeph Sholom was an Orthodox congregation, with services exclusively in Hebrew, although they did not have daily minyan services. A few years after Rabbi Esserman died, despite the small size of the congregation, Rodeph Sholom was able to hire another full-time rabbi, Morris Miller, who stayed in Rome for six years. While there were a few years when the congregation did not have a rabbi, Rodeph Sholom was largely able to maintain a full-time rabbi until 1956.

Like Rome itself, the city’s Jewish community rose from these ashes after the war. By 1870, Jacob Cohen, Morris Marks, and David Meyerhardt were still flourishing merchants in Rome; in fact, the value of their real estate holdings had increased significantly during the turbulent decade. After the war, Rome’s Jewish population grew. Prussian-born Jacob Kuttner moved to Rome from New York in 1871, opening a dry goods store. Kuttner’s sons, Max and Sam, took over the business after he died in 1905. Jacob Kuttner’s daughter Hilda married a young Alsatian immigrant named Isaac May, who had come to Rome in the early 1880s from Muncie, Indiana, where he had worked as a store clerk. May became a longtime dry goods merchant in Rome and a leading member of the local Jewish community.

Rodeph Sholom

In 1875, the growing number of Jews in Rome, led by David Meyerhardt, organized a congregation, Rodeph Sholom. Its name, which means “Pursuers of Peace,” was certainly salient in a region still working to recover from the Civil War and Reconstruction. Soon after, Jacob Cohen donated land to the congregation on Mount Aventine for use as a cemetery. Initially, the group met in private homes, though by 1890 they were meeting on the second floor of the local Masonic Temple, which remained the congregations home for the next 50 years. The congregation founded a religious school which also met at the Masonic Temple. The congregation was led by the same family for its first 60 years. Philip Cohen was the first president of Rodeph Shalom, serving for ten years. He was succeeded in 1885 by his brother-in-law, Jacob Kuttner, who led the congregation until his death in 1905. Kuttner’s son-in-law, Isaac May, then took over the reins, serving as president until 1938.

The Early 20th Century

In the early 20th century, an influx of Jewish immigrants from the Russian empire began to arrive in Rome. Jacob Mendelson left Russia in 1896, and settled in Rome by 1905, where he opened a dry goods store. Two brothers, Pressley and Joe Esserman, left Russia in 1891; by 1896, they had settled in Rome and opened Esserman’s Store, which remained in business for almost a century. According to family lore, Pressley learned English by going to the local Baptist Church, where he heard them read the Old Testament, which he could translate into Hebrew. After a few years in business in Rome, the brothers were able to bring over the rest of their family, including their parents, David and Lena Esserman, and four younger brothers in 1898. Initially, the entire family lived together above the store on Broad Street.

This wave of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe pushed Rome’s Jewish community from 104 Jews in 1907 to a peak of 250 Jews in 1919. Most of these were concentrated in retail trade, and Jewish-owned businesses lined the streets of Rome’s downtown. The community was made up of large families; in 1922, almost 60 children were in the Rodeph Sholom religious school.

David Esserman was a rabbi by training, and became the spiritual leader of Rodeph Sholom until his death in 1917. He brought a Torah with him to Rome that was used by the congregation. Rodeph Sholom was an Orthodox congregation, with services exclusively in Hebrew, although they did not have daily minyan services. A few years after Rabbi Esserman died, despite the small size of the congregation, Rodeph Sholom was able to hire another full-time rabbi, Morris Miller, who stayed in Rome for six years. While there were a few years when the congregation did not have a rabbi, Rodeph Sholom was largely able to maintain a full-time rabbi until 1956.

Rodeph Sholom

Rodeph Sholom

Rodeph Sholom in the 20th Century

By the 1930s, the congregation began to discuss building a permanent synagogue, which it had not done in the six decades of its existence. In 1937, member Abe Abramson, who was a farmer in nearby Adairsville, left a large bequest to Rodeph Sholom, which became the foundation of a building fund. The congregation purchased land on East First Street from St. Peter’s Episcopal Church, which was located next door. In March of 1938, they dedicated a small, unassuming building on the site, which cost $15,600, and could seat 200 people in its sanctuary. According to the local newspaper, “it was the generous support of the many friends…of Jewish, Protestant, and Catholic faith that made possible the erection of the house of worship.” At the dedication, Rabbi Harry Epstein of Atlanta’s Ahavath Achim congregation led the service and was the keynote speaker. The pastor of the local First Baptist Church also spoke during the dedication ceremony, as did the editor of the local newspaper, who called the synagogue a “splendid contribution to the moral and spiritual progress of the city.”

During the 1930s and 1940s, the congregation was slowly moving toward Reform Judaism. In 1931, Rodeph Sholom held its first confirmation ceremony, with the assistance of Rabbi Benjamin Parker from Chattanooga’s Reform congregation. During the ceremony, each of the seven confirmants gave a speech before the service closed with the singing of “America.” A congregation Sisterhood was founded in 1937 and affiliated with the Reform National Federation of Temple Sisterhoods. In 1950, the congregation used the Reform Union Prayer Book, but still held services on the traditional two days for Rosh Hashanah. The congregation voted to limit Rosh Hashanah observance to one day in 1965. Finally, the congregation officially joined the Reform Union of American Hebrew Congregations in 1955. Some members were upset at the change, and at least one quit the congregation, but Rodeph Sholom ultimately benefited from the affiliation. As members of the UAHC, they were now able to bring down student rabbis from the Reform seminary, Hebrew Union College. From 1956 to 1995, Rodeph Sholom received regular visits from HUC rabbinic students. In 1966, Rodeph Sholom continued their movement away from traditional Judaism when members voted to stop maintaining a kosher kitchen in the synagogue, though they agreed “no hog meat would be brought into the kitchen.”

By the 1930s, the congregation began to discuss building a permanent synagogue, which it had not done in the six decades of its existence. In 1937, member Abe Abramson, who was a farmer in nearby Adairsville, left a large bequest to Rodeph Sholom, which became the foundation of a building fund. The congregation purchased land on East First Street from St. Peter’s Episcopal Church, which was located next door. In March of 1938, they dedicated a small, unassuming building on the site, which cost $15,600, and could seat 200 people in its sanctuary. According to the local newspaper, “it was the generous support of the many friends…of Jewish, Protestant, and Catholic faith that made possible the erection of the house of worship.” At the dedication, Rabbi Harry Epstein of Atlanta’s Ahavath Achim congregation led the service and was the keynote speaker. The pastor of the local First Baptist Church also spoke during the dedication ceremony, as did the editor of the local newspaper, who called the synagogue a “splendid contribution to the moral and spiritual progress of the city.”

During the 1930s and 1940s, the congregation was slowly moving toward Reform Judaism. In 1931, Rodeph Sholom held its first confirmation ceremony, with the assistance of Rabbi Benjamin Parker from Chattanooga’s Reform congregation. During the ceremony, each of the seven confirmants gave a speech before the service closed with the singing of “America.” A congregation Sisterhood was founded in 1937 and affiliated with the Reform National Federation of Temple Sisterhoods. In 1950, the congregation used the Reform Union Prayer Book, but still held services on the traditional two days for Rosh Hashanah. The congregation voted to limit Rosh Hashanah observance to one day in 1965. Finally, the congregation officially joined the Reform Union of American Hebrew Congregations in 1955. Some members were upset at the change, and at least one quit the congregation, but Rodeph Sholom ultimately benefited from the affiliation. As members of the UAHC, they were now able to bring down student rabbis from the Reform seminary, Hebrew Union College. From 1956 to 1995, Rodeph Sholom received regular visits from HUC rabbinic students. In 1966, Rodeph Sholom continued their movement away from traditional Judaism when members voted to stop maintaining a kosher kitchen in the synagogue, though they agreed “no hog meat would be brought into the kitchen.”

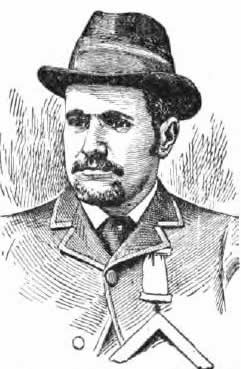

Max Meyerhardt

Max Meyerhardt

Civic Engagement

Over the years, Rome Jews have become important leaders in the larger community. Isaac May spent several years on the city council in the 1910s and 1920s. For a time, he was chairman of the Rome City Council. Perhaps the most prominent member of the Jewish community was Max Meyerhardt. Born in Prussia in 1855, Max came to Rome with his parents, David and Esther, as a young boy. Max became a prominent local lawyer, and served as a city judge from 1879 to 1891. He later served as the city attorney. Meyerhardt was a fierce advocate for public education and helped to found Rome's public school system in 1884; he served on the Rome School Board for 25 years. He was also dedicated to the idea of public libraries and was a founder of the local Young Men’s Library Association. He brought Rabbi E.B.M. Browne to Rome in 1899 for a series of lectures to raise money for the library fund. Finally, Meyerhardt convinced the city council to raise the matching money required to apply for a Carnegie Library Grant. Thanks to Meyerhardt’s leadership, Rome’s Carnegie Library opened in 1911. Meyerhardt was also very active in the Masons, and spent seven years as the Grand Worshipful Master of Masonry for the entire State of Georgia. Max Meyerhardt was also a leader of the Rome Jewish community. His passion for education inspired him to found Rodeph Sholom’s religious school, which he ran for almost 50 years. During World War I, Meyerhardt led the campaign for Jewish war relief in Europe, using the social connections he gained through the Masons to raise money from non-Jews across the state.

World War II

During World War II, 27 men from Rodeph Sholom served in the military; one, Solomon Bredosky, died during the D-Day invasion. Those who remained on the homefront also did their part for the war effort. The Jewish Welfare Board was in charge of the USO in Rome during the war. Members of Rodeph Sholom served as USO hostesses and helped the wounded soldiers at the local army hospital. The congregation lent a Torah that was used for Friday night services at the hospital’s chapel, while the Rodeph Sholom Sisterhood hosted weekly oneg receptions there. In addition to their wartime work, the Sisterhood also raised money to support the congregation and its new synagogue and oversaw the religious school. The Sisterhood was also affiliated with Hadassah.

Around the time of World War II, Rome increasingly attracted industry, including carpet factories and a rayon plant. Charles Heyman, who had started as an office boy at the Fox Manufacturing Company in Atlanta in 1920, eventually bought the company and moved its operations to Rome in 1936. The company manufactured furniture that was sold in stores around the country. Heyman moved his family to Rome two years later. His son Lyons Heyman joined the company as one of 30 traveling salesmen in 1948, and later became president in 1965. In 1980, he sold the company.

Over the years, Rome Jews have become important leaders in the larger community. Isaac May spent several years on the city council in the 1910s and 1920s. For a time, he was chairman of the Rome City Council. Perhaps the most prominent member of the Jewish community was Max Meyerhardt. Born in Prussia in 1855, Max came to Rome with his parents, David and Esther, as a young boy. Max became a prominent local lawyer, and served as a city judge from 1879 to 1891. He later served as the city attorney. Meyerhardt was a fierce advocate for public education and helped to found Rome's public school system in 1884; he served on the Rome School Board for 25 years. He was also dedicated to the idea of public libraries and was a founder of the local Young Men’s Library Association. He brought Rabbi E.B.M. Browne to Rome in 1899 for a series of lectures to raise money for the library fund. Finally, Meyerhardt convinced the city council to raise the matching money required to apply for a Carnegie Library Grant. Thanks to Meyerhardt’s leadership, Rome’s Carnegie Library opened in 1911. Meyerhardt was also very active in the Masons, and spent seven years as the Grand Worshipful Master of Masonry for the entire State of Georgia. Max Meyerhardt was also a leader of the Rome Jewish community. His passion for education inspired him to found Rodeph Sholom’s religious school, which he ran for almost 50 years. During World War I, Meyerhardt led the campaign for Jewish war relief in Europe, using the social connections he gained through the Masons to raise money from non-Jews across the state.

World War II

During World War II, 27 men from Rodeph Sholom served in the military; one, Solomon Bredosky, died during the D-Day invasion. Those who remained on the homefront also did their part for the war effort. The Jewish Welfare Board was in charge of the USO in Rome during the war. Members of Rodeph Sholom served as USO hostesses and helped the wounded soldiers at the local army hospital. The congregation lent a Torah that was used for Friday night services at the hospital’s chapel, while the Rodeph Sholom Sisterhood hosted weekly oneg receptions there. In addition to their wartime work, the Sisterhood also raised money to support the congregation and its new synagogue and oversaw the religious school. The Sisterhood was also affiliated with Hadassah.

Around the time of World War II, Rome increasingly attracted industry, including carpet factories and a rayon plant. Charles Heyman, who had started as an office boy at the Fox Manufacturing Company in Atlanta in 1920, eventually bought the company and moved its operations to Rome in 1936. The company manufactured furniture that was sold in stores around the country. Heyman moved his family to Rome two years later. His son Lyons Heyman joined the company as one of 30 traveling salesmen in 1948, and later became president in 1965. In 1980, he sold the company.

The Civil Rights Era

During the civil rights era, some Rome Jews worked to achieve the peaceful integration of the city. Jule Levin had come to Rome in 1940 and married Rose Esserman, the daughter of Pressley and Annie Esserman. He worked at Esserman’s Department Store, which was among the first in Rome to treat their black customers with terms of respect, calling them “Mr.” and “Mrs.” It was also the first store in downtown Rome that employed black salespeople to wait on both white and black customers. Levin was president of the Rome Chamber of Commerce when black activists began to sit-in and protest segregation at the city’s downtown stores. He worked to convince other business owners that integration was in their best interest so Rome could avoid the violence that plagued other Southern cities. During a series of lunch counter sit-ins by local black students in 1963, Levin helped to negotiate a peaceful settlement. Jule’s wife Rose was active in the pro-civil rights Georgia Council of Human Relations and fought against public school closings during the struggle over integration. To honor her parents’ commitment to building a more just society, Ann Levin and her husband Larry Beeferman created the Rose Esserman Levin and Jule Gordon Levin Fund for Social Justice in 1993. The fund gives an award each year to the high school senior in Rome whose actions best exemplify the ideal of social justice.

During the civil rights era, some Rome Jews worked to achieve the peaceful integration of the city. Jule Levin had come to Rome in 1940 and married Rose Esserman, the daughter of Pressley and Annie Esserman. He worked at Esserman’s Department Store, which was among the first in Rome to treat their black customers with terms of respect, calling them “Mr.” and “Mrs.” It was also the first store in downtown Rome that employed black salespeople to wait on both white and black customers. Levin was president of the Rome Chamber of Commerce when black activists began to sit-in and protest segregation at the city’s downtown stores. He worked to convince other business owners that integration was in their best interest so Rome could avoid the violence that plagued other Southern cities. During a series of lunch counter sit-ins by local black students in 1963, Levin helped to negotiate a peaceful settlement. Jule’s wife Rose was active in the pro-civil rights Georgia Council of Human Relations and fought against public school closings during the struggle over integration. To honor her parents’ commitment to building a more just society, Ann Levin and her husband Larry Beeferman created the Rose Esserman Levin and Jule Gordon Levin Fund for Social Justice in 1993. The fund gives an award each year to the high school senior in Rome whose actions best exemplify the ideal of social justice.

Late 20th Century Changes

For much of the twentieth century, most Roman Jews engaged in retail trade. Esserman’s Department Store remained a fixture on Broad Street; a cousin, Joseph Esserman, owned the Lad & Lassie children’s clothing store. Isadore Levenson owned The Vogue, a ladies dress store. Louis Gavant, who moved to Rome from Atlanta in 1939, opened the National Jewelry and Loan Company. By the 1980s, many of these businesses had started to close. Esserman’s store finally closed around 1990, just short of reaching its 100th anniversary.

These closings were a result of larger changes in the retail industry as well as Jewish children who chose to pursue professional occupations rather than working in the family store. These trends took their toll on the Rome Jewish community, which shrank from 200 Jews in 1937 to fewer than 100 by the end of the 1970s. Rodeph Sholom had 46 member families in 1966; by 1979, they only had 33 members, and were struggling to afford the expense of a student rabbi. By the early 1970s, only four children were in the religious school, and Rodeph Sholom seemed to be a congregation headed for extinction.

Despite these challenges, Rodeph Sholom has thrived in recent decades, as an influx of Jewish professionals has helped offset the disappearance of the town’s Jewish merchants. One of the earliest was Murray Stein, a dentist, who came to Rome in 1951. Stein became a leader of the local Jewish community, heading the campaign that raised $10,000 for the UJA Emergency Fund during Israel’s 1967 War. He was one of the first white dentists to treat African American patients during the civil rights era. In recent decades, increasing numbers of Jewish professionals have come to work at Rome’s growing medical center or to teach at Berry College.

For much of the twentieth century, most Roman Jews engaged in retail trade. Esserman’s Department Store remained a fixture on Broad Street; a cousin, Joseph Esserman, owned the Lad & Lassie children’s clothing store. Isadore Levenson owned The Vogue, a ladies dress store. Louis Gavant, who moved to Rome from Atlanta in 1939, opened the National Jewelry and Loan Company. By the 1980s, many of these businesses had started to close. Esserman’s store finally closed around 1990, just short of reaching its 100th anniversary.

These closings were a result of larger changes in the retail industry as well as Jewish children who chose to pursue professional occupations rather than working in the family store. These trends took their toll on the Rome Jewish community, which shrank from 200 Jews in 1937 to fewer than 100 by the end of the 1970s. Rodeph Sholom had 46 member families in 1966; by 1979, they only had 33 members, and were struggling to afford the expense of a student rabbi. By the early 1970s, only four children were in the religious school, and Rodeph Sholom seemed to be a congregation headed for extinction.

Despite these challenges, Rodeph Sholom has thrived in recent decades, as an influx of Jewish professionals has helped offset the disappearance of the town’s Jewish merchants. One of the earliest was Murray Stein, a dentist, who came to Rome in 1951. Stein became a leader of the local Jewish community, heading the campaign that raised $10,000 for the UJA Emergency Fund during Israel’s 1967 War. He was one of the first white dentists to treat African American patients during the civil rights era. In recent decades, increasing numbers of Jewish professionals have come to work at Rome’s growing medical center or to teach at Berry College.

The Jewish Community in Rome Today

This small wave of Jewish professionals has bolstered Rodeph Sholom. In 1991, they were able to acquire a lot next to the synagogue to use for parking. In 1995, they ended their longtime relationship with Hebrew Union College and hired Rabbi Scott Saulson of Atlanta to lead services in Rome once a month. Rabbi Saulson served as visiting rabbi at Rodeph Sholom for ten years. Currently, Rabbi Judith Beiner of Atlanta travels once a month to Rome to lead services and Torah study and work with the religious school. In 2008, they undertook a $350,000 renovation to their building. While Rodeph Sholom remains small, it continues to be an active and vibrant congregation.