Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Congregations - Alexandria, Louisiana

Jews did not wait long after their arrival in Alexandria and Rapides Parish to come together and organize a congregation. Under the leadership of Isaac Levy, Henry Greenwood, and Julius Levin, a small group of families formed Congregation Gemiluth Chassodim, known then as the Hebrew Benevolent Society of Rapides Parish, in early October, 1859. The congregation, as its first order of business, purchased a cemetery owned by a small group of Jewish families across the Red River in Pineville. Several explanations exist as to why a Jewish cemetery predated the organization of Gemiluth Chassodim. One belief is that certain families bought a burial ground when a small outbreak of yellow fever claimed six Jewish lives in the early 1850s; another explanation proposed by Rabbi Martin Hinchin is that these families had been hurriedly formed to arrange for the burial of a “strange and unknown Jew” that arrived in Alexandria.

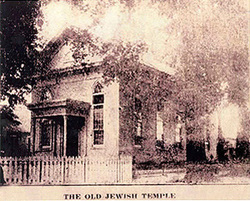

Soon thereafter, the Jewish women of Alexandria assembled to found the Ladies’ Hebrew Benevolent Society to raise money to buy real estate on which a temple could be built. The Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Society eventually changed its name to the Temple Sisterhood and, in 1869, held a fundraising ball to raise money to build a temple downtown at the corner of Third and Fiske Streets. Construction of the temple concluded in 1871 and two years later, the congregation joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations and hired Rabbi Marx Klein as its first full-time spiritual leader. During Rabbi Klein’s six-year tenure at Gemiluth Chassodim, the congregation grew to forty-two members, organized a religious school of thirty students, and increased its operating budget to eleven hundred dollars. Rabbi Klein resigned as rabbi in 1879 and in later years served other growing congregations in Louisiana, including Temple Sinai in Saint Francisville and Bikur Cholim in Donaldsonville.

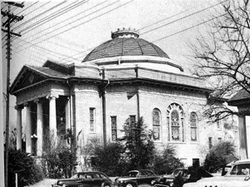

By the first decade of the twentieth century, Gemiluth Chassodim had developed into one of the largest congregations in Louisiana. Records from 1908 indicate that the congregation boasted a membership of sixty-eight families, services on Shabbat and holidays in the evening and morning, a budget that had grown twofold in thirty years, and a large Sunday school with six teachers and fifty-eight students. The sisterhood planned an active social calendar for the congregation’s members, including annual Purim masquerade balls, Simchat Torah balls, Children’s masquerades, and Hanukah festivals of which, according to lifelong Alexandrian Joan Pressburg, “even gentile friends were a bit jealous.” In 1908, the congregation built a new synagogue with a sanctuary that could seat 450 people.

By the first decade of the twentieth century, Gemiluth Chassodim had developed into one of the largest congregations in Louisiana. Records from 1908 indicate that the congregation boasted a membership of sixty-eight families, services on Shabbat and holidays in the evening and morning, a budget that had grown twofold in thirty years, and a large Sunday school with six teachers and fifty-eight students. The sisterhood planned an active social calendar for the congregation’s members, including annual Purim masquerade balls, Simchat Torah balls, Children’s masquerades, and Hanukah festivals of which, according to lifelong Alexandrian Joan Pressburg, “even gentile friends were a bit jealous.” In 1908, the congregation built a new synagogue with a sanctuary that could seat 450 people.

While the congregation was stronger than ever before, two issues concerned members of Gemiluth Chassodim. First, rabbis experienced short tenures in Alexandria. There is no evidence to support the presence of bureaucratic disputes over rabbis, but between Rabbi Klein’s departure in 1879 and the arrival of Rabbi Leonard Rothstein in 1907, nine rabbis served Gemiluth Chassodim. Rabbi Rothstein remained in Alexandria until the end of the First World War.

Second, the more devout members, many of them Russian and Polish immigrants who had arrived in Alexandria since 1885, found that the congregation wasn’t fulfilling their religious needs. In response, these members left Gemiluth Chassodim in 1913 to found B’nai Israel, an orthodox synagogue. Their first synagogue was located at Fourth and Lee Streets. Ten years after B’nai Israel’s foundation, the congregation had twenty members, the full-time services of Rabbi Jacob Aronson, weekly services, and an intensive religious school program that met three times per week. The religious school soon thereafter met six days per week that “provided instruction in Hebrew language, history, and the Bible.” Already by 1924, as an article on Alexandria’s Jewish Community in the Jewish Ledger of New Orleans notes, B’nai Israel thrived despite being the smaller and newer congregation in the city: “The Orthodox congregation of the city worships in a separate synagogue. With a membership of only twenty [families] they maintain a Rabbi and a Hebrew School.” By 1940, the congregation had its own building and a small cemetery just north of the city. It is important to note, however, that these two congregations coexisted peacefully despite differences in religious observance and doctrine. “No friction between the two elements exists,” the article asserted. “In fact, quite a number of Jews in Alexandria belong to both, Congregation Gemiluth Chassodim and Congregation B’nai Israel.”

Second, the more devout members, many of them Russian and Polish immigrants who had arrived in Alexandria since 1885, found that the congregation wasn’t fulfilling their religious needs. In response, these members left Gemiluth Chassodim in 1913 to found B’nai Israel, an orthodox synagogue. Their first synagogue was located at Fourth and Lee Streets. Ten years after B’nai Israel’s foundation, the congregation had twenty members, the full-time services of Rabbi Jacob Aronson, weekly services, and an intensive religious school program that met three times per week. The religious school soon thereafter met six days per week that “provided instruction in Hebrew language, history, and the Bible.” Already by 1924, as an article on Alexandria’s Jewish Community in the Jewish Ledger of New Orleans notes, B’nai Israel thrived despite being the smaller and newer congregation in the city: “The Orthodox congregation of the city worships in a separate synagogue. With a membership of only twenty [families] they maintain a Rabbi and a Hebrew School.” By 1940, the congregation had its own building and a small cemetery just north of the city. It is important to note, however, that these two congregations coexisted peacefully despite differences in religious observance and doctrine. “No friction between the two elements exists,” the article asserted. “In fact, quite a number of Jews in Alexandria belong to both, Congregation Gemiluth Chassodim and Congregation B’nai Israel.”

Both the reform and orthodox congregations in Alexandria grew in the mid-twentieth century. Gemiluth Chassodim experienced a rapid increase in its membership, from 123 families in 1925, to 154 families in 1930 and 203 families in 1945. Rabbi Albert Baum, who had led the congregation during this period of growth, resigned in 1942 to enlist in the United States Navy and fight in World War II. Unfortunately, the synagogue, which had been praised for its exceptional architecture, burned down in 1956. With amazing foresight, however, the congregation had already built another temple before the fire and moved swiftly into this new building. This third temple building, while not as ornate as the second, proved much more accessible to an older Jewish population who were attending services. In 1958, Rabbi Martin Hinchin arrived in Alexandria and led the congregation for thirty-one years. He researched the history of Alexandria’s Jewish community extensively and wrote a local history entitled Fourscore and Eleven: A History of the Jews of Rapides Parish, 1828-1919.

In the early and mid twentieth century, B’nai Israel also experienced an increase in its membership, which enabled them to build a new synagogue in 1932 located only two blocks away from Gemiluth Chassodim. Religious school met six times per week in the synagogue, providing instruction in Hebrew, Jewish history, and Torah. The members of B’nai Israel, however, were unable to hire a rabbi after the end of the Second World War. By 1980, the Kaplan family coordinated the congregation, which had recently changed its affiliation from orthodox to conservative. Most members of B’nai Israel today are also members of Gemiluth Chassodim, known colloquially as “the temple,” and there are often joint services on various holidays and festivals. On High Holidays, a chazzan travels from Dallas to Alexandria and officiates their services. Their membership numbers have declined in recent years, but those who remain have demonstrated their constant devotion to maintaining the congregation and its religious practices.

In the early and mid twentieth century, B’nai Israel also experienced an increase in its membership, which enabled them to build a new synagogue in 1932 located only two blocks away from Gemiluth Chassodim. Religious school met six times per week in the synagogue, providing instruction in Hebrew, Jewish history, and Torah. The members of B’nai Israel, however, were unable to hire a rabbi after the end of the Second World War. By 1980, the Kaplan family coordinated the congregation, which had recently changed its affiliation from orthodox to conservative. Most members of B’nai Israel today are also members of Gemiluth Chassodim, known colloquially as “the temple,” and there are often joint services on various holidays and festivals. On High Holidays, a chazzan travels from Dallas to Alexandria and officiates their services. Their membership numbers have declined in recent years, but those who remain have demonstrated their constant devotion to maintaining the congregation and its religious practices.

In the last twenty years, Gemiluth Chassodim has also experienced a decline in membership. While the congregation boasted 161 families in 1985 and even two rabbis in 1995, only 110 families belong today. Although its membership numbers are decreasing, the congregation, under the leadership of Rabbi Arnie Task, has emerged as a regional hub, attracting Jewish families from throughout central and southern Louisiana. On many weekends, families commute from Lafayette, Leesville, Natchitoches, and Winnfield to Alexandria for services or religious school. One family even commutes over two hours from Sulphur each week. The congregation continues to thrive today as its members demonstrate an unwavering commitment to maintaining a strong Jewish presence in Alexandria.