Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Congregation Agudath Achim - Shreveport , Louisiana

As early as 1884, Orthodox Jews were praying together informally in Shreveport. During the closing decades of the 19th century, increasing numbers of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe settled in Shreveport. For the most part, these arrivals adhered more strictly to traditional Jewish practices, and by the turn of the century, two separate groups were holding regular Orthodox services.

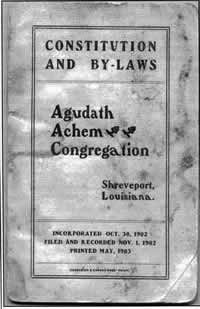

Sam Willer came to the United States from Russia in 1888, settling in Bossier Parish. In Shreveport, he found five practicing Orthodox families. Willer joined this small group, which called themselves Beth El (House of God), helping them to achieve a minyan. Henry Goldman, a Russian-born dry goods merchant who had recently moved to Shreveport from Texas, served as lay leader of the small congregation. They met in various buildings on Texas Street, including Bogel’s Hall. Beth El members bought land for a cemetery on Walnut Street through their burial group, Chessed Shel Emeth. Around the same time, Levi Groner was president of another small Orthodox congregation in Shreveport named Beth Joseph. Realizing that they needed to band together to survive, the two congregations merged and adopted the name Agudath Achim (Society of Brothers) in 1902. The new combined congregation, which totaled 58 original members, assumed ownership of the Orthodox burial grounds, which became known as Agudath Achim Cemetery, or Orthodox Hebrew Rest.

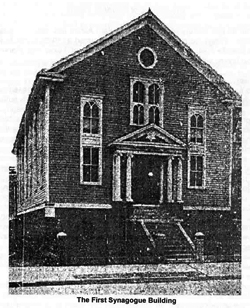

In 1904, the congregation began construction of a new synagogue, but work was soon halted due to one of the outbreaks of yellow fever that frequently plagued the city. The strain of the epidemic posed a serious challenge to the new congregation’s synagogue construction project. At the height of the epidemic, trains were forbidden to enter or leave the city, and health officials fumigated every home in the town. The small community lost members, and those remaining lacked the funds to continue the synagogue construction project.

Sam Willer came to the United States from Russia in 1888, settling in Bossier Parish. In Shreveport, he found five practicing Orthodox families. Willer joined this small group, which called themselves Beth El (House of God), helping them to achieve a minyan. Henry Goldman, a Russian-born dry goods merchant who had recently moved to Shreveport from Texas, served as lay leader of the small congregation. They met in various buildings on Texas Street, including Bogel’s Hall. Beth El members bought land for a cemetery on Walnut Street through their burial group, Chessed Shel Emeth. Around the same time, Levi Groner was president of another small Orthodox congregation in Shreveport named Beth Joseph. Realizing that they needed to band together to survive, the two congregations merged and adopted the name Agudath Achim (Society of Brothers) in 1902. The new combined congregation, which totaled 58 original members, assumed ownership of the Orthodox burial grounds, which became known as Agudath Achim Cemetery, or Orthodox Hebrew Rest.

In 1904, the congregation began construction of a new synagogue, but work was soon halted due to one of the outbreaks of yellow fever that frequently plagued the city. The strain of the epidemic posed a serious challenge to the new congregation’s synagogue construction project. At the height of the epidemic, trains were forbidden to enter or leave the city, and health officials fumigated every home in the town. The small community lost members, and those remaining lacked the funds to continue the synagogue construction project.

In this period of great trial, the citizens of Shreveport exemplified the spirit of solidarity and friendship that often arises from adversity. When news spread of Agudath Achim’s setbacks, Jews and Christians from across the city stepped forward to provide the needed funds. On September 8, 1905, much of the town crowded into Agudath Achim’s “magnificent edifice” to participate in the new synagogue’s consecration service. Speakers included Agudath Achim’s Rabbi H. Wolenski and Shreveport Mayor Andrew Querbes. The crowd also included city council members, members of the Reform B’nai Zion Congregation, the Catholic chief of the Shreveport Fire Department, and many prominent local figures.

Members of Agudath Achim sought opportunities to reciprocate the kindness shown them by their neighbors. In 1905, Agudath Achim’s, Rabbi Getzler organized a Hebrew School which, in addition to instructing young congregation members, was opened to anyone in the Shreveport community interested in learning Hebrew. The congregation also created a weekly Sunday School. By 1907, Agudath Achim had 65 members and an annual income of $2500. They held a daily minyan in Hebrew every morning.

Although the congregation was nominally Orthodox, Agudath Achim began to introduce changes in their traditional worship early in their history. They started to hold additional services on Friday night with sermons from the rabbi in Yiddish and later English. Their first synagogue had been built with a balcony for women to sit apart from the men. But in 1919, women were allowed to sit on the ground floor with men except on the high holidays. Eventually, the congregation allowed mixed gender seating for all services.

Members of Agudath Achim sought opportunities to reciprocate the kindness shown them by their neighbors. In 1905, Agudath Achim’s, Rabbi Getzler organized a Hebrew School which, in addition to instructing young congregation members, was opened to anyone in the Shreveport community interested in learning Hebrew. The congregation also created a weekly Sunday School. By 1907, Agudath Achim had 65 members and an annual income of $2500. They held a daily minyan in Hebrew every morning.

Although the congregation was nominally Orthodox, Agudath Achim began to introduce changes in their traditional worship early in their history. They started to hold additional services on Friday night with sermons from the rabbi in Yiddish and later English. Their first synagogue had been built with a balcony for women to sit apart from the men. But in 1919, women were allowed to sit on the ground floor with men except on the high holidays. Eventually, the congregation allowed mixed gender seating for all services.

The congregation grew quickly, and by 1925, members already began looking for a site to build a larger synagogue. Although the congregation purchased a site the following year at the corner of Line Avenue and Herndon Street, construction did not begin until 1938. The cornerstone laying ceremony once again attracted a broad cross-section of the Shreveport citizenry, including the Mayor Sam Caldwell, B’nai Zion’s Rabbi Abram Brill, the leaders of many churches, and local business figures. In 1950, the congregation added a large community center in the back of the synagogue, including space for a gymnasium/social hall, classrooms, a small chapel, and a mikveh.

In 1966, the congregation decided to buy property for a new synagogue. But since the Jewish community of Shreveport was declining, some questioned the wisdom of building a new house of worship. In 1955, there had been 286 member families at Agudath Achim; by 1968, membership was down to 200, and would continue to decline. In 1974, they refurbished their old building, but they finally decided that the upkeep on their old, large building was too much, and that most members had moved to other parts of town. In 1981, they completed work on the new synagogue on Village Green Drive, which remains Agudath Achim’s home today.

Over the years, Agudath Achim has had eighteen rabbis, most of whom have stayed only a few years. Leo Brener was the great exception, leading the congregation for forty years, from 1934 to 1974. Born in New Orleans to Polish immigrant parents, Rabbi Brener received both a secular and a religious education, earning a master’s degree from the University of Chicago before being ordained by the Hebrew Theological College. Agudath Achim was the first and only pulpit he held during his career. When other congregations tried to lure Rabbi Brener away, he would decline their offers, writing in one instance, “I find in Shreveport a fruitful field. I believe I have the opportunity to help build and strengthen Jewish life in this community.” Rabbi Brener was active in the local Zionist District and served on the national board of Young Judea. After he retired in 1974, he remained as rabbi emeritus until his death in 1989.

In 1966, the congregation decided to buy property for a new synagogue. But since the Jewish community of Shreveport was declining, some questioned the wisdom of building a new house of worship. In 1955, there had been 286 member families at Agudath Achim; by 1968, membership was down to 200, and would continue to decline. In 1974, they refurbished their old building, but they finally decided that the upkeep on their old, large building was too much, and that most members had moved to other parts of town. In 1981, they completed work on the new synagogue on Village Green Drive, which remains Agudath Achim’s home today.

Over the years, Agudath Achim has had eighteen rabbis, most of whom have stayed only a few years. Leo Brener was the great exception, leading the congregation for forty years, from 1934 to 1974. Born in New Orleans to Polish immigrant parents, Rabbi Brener received both a secular and a religious education, earning a master’s degree from the University of Chicago before being ordained by the Hebrew Theological College. Agudath Achim was the first and only pulpit he held during his career. When other congregations tried to lure Rabbi Brener away, he would decline their offers, writing in one instance, “I find in Shreveport a fruitful field. I believe I have the opportunity to help build and strengthen Jewish life in this community.” Rabbi Brener was active in the local Zionist District and served on the national board of Young Judea. After he retired in 1974, he remained as rabbi emeritus until his death in 1989.

During its early decades, Agudath Achim also employed a kosher butcher, or shochet. The shochet often doubled as a cantor, chanting prayers during religious services. In some cases, he also served the congregation as a mohel, performing circumcisions on newborn boys. That this new congregation felt committed to hiring a kosher butcher reflected the members’ desire to maintain traditional Jewish worship in a city that lacked the religious resources of many larger communities. In 1920, they paid their shochet-cantor $1800 a year, which, coupled with the $2400 they were paying their rabbi, reflected the financial strength of the congregation. The appropriately named Jacob Cantor served as the shochet-cantor from 1920 to 1933. Dues-paying members of Agudas Achim did not have to pay for the shochet’s services; non-members were assessed a monthly fee. The congregation’s Kashrut Committee would set the prices for kosher meat; the shochet would often petition the committee for the right to raise his prices. In 1927, Cantor resigned as shochet so he could have control over the prices in his butcher shop, although the board convinced him to slaughter members’ animals for free in return for a small monthly salary.

Elias Atlas replaced Cantor in 1934. Atlas started out working at the local Piggly Wiggly grocery store, but soon established his own kosher meat market and delicatessen, though it was supervised and its prices set by the congregation’s Kashrut Committee. When Atlas moved to Tyler, Texas in 1943, he would still come back to Shreveport periodically to slaughter animals for Agudas Achim members. The congregation’s monthly bulletin would list the schecting hours and locations. In 1955, when there was no longer a kosher butcher in town, the congregation made an arrangement with a local grocery store to bring in a shochet from Dallas twice a month. Members were told to plan ahead and get several weeks worth of poultry and meat when it was available. By 1970, there was no longer any kosher meat slaughtered in Shreveport as stores did not find it profitable to carry kosher meat anymore. While Agudath Achim continued to hire cantors, they no longer doubled as kosher butchers.

This gradual drift away from Orthodox practice was made official in 1965 when the congregation voted to join the Conservative Movement. Agudath Achim evolved along with the Conservative Movement on gender issues. In 1977, they allowed women to be called up for torah prayers (aliyah), and in 1981, they decided to count women towards the minyan, as long as there were at least six men in the group. In 1993, they removed any gender restrictions from the minyan.

Elias Atlas replaced Cantor in 1934. Atlas started out working at the local Piggly Wiggly grocery store, but soon established his own kosher meat market and delicatessen, though it was supervised and its prices set by the congregation’s Kashrut Committee. When Atlas moved to Tyler, Texas in 1943, he would still come back to Shreveport periodically to slaughter animals for Agudas Achim members. The congregation’s monthly bulletin would list the schecting hours and locations. In 1955, when there was no longer a kosher butcher in town, the congregation made an arrangement with a local grocery store to bring in a shochet from Dallas twice a month. Members were told to plan ahead and get several weeks worth of poultry and meat when it was available. By 1970, there was no longer any kosher meat slaughtered in Shreveport as stores did not find it profitable to carry kosher meat anymore. While Agudath Achim continued to hire cantors, they no longer doubled as kosher butchers.

This gradual drift away from Orthodox practice was made official in 1965 when the congregation voted to join the Conservative Movement. Agudath Achim evolved along with the Conservative Movement on gender issues. In 1977, they allowed women to be called up for torah prayers (aliyah), and in 1981, they decided to count women towards the minyan, as long as there were at least six men in the group. In 1993, they removed any gender restrictions from the minyan.

Even when they couldn’t be counted for a minyan, women played an important role in the development of Agudath Achim. In 1916, the women of the congregation founded the Ladies Auxiliary, which held monthly meetings featuring educational lectures and entertainment programs. Since most early members had grown up when Orthodox women received little formal Jewish education, the Ladies Auxiliary was very active in offering Jewish education to its membership. In the late 1940s and 1950s, it held regular classes, led by the wife of Rabbi Brener, on conversational Hebrew, Jewish history, and the Bible. The group also held numerous fundraisers to help support the synagogue. In 1959, the Ladies Auxiliary changed its name to the Sisterhood, and joined the Women’s League of United Synagogue, the national organization of Conservative sisterhoods. Interestingly, this was six years before the congregation itself decided to join the Conservative Movement.

By 1946, the congregation began to have a hard time finding ten men to make up the daily minyan, so they instituted a draft whereby other members would be assigned each week to make the minyan. Members were promised that they would not be drafted for more than two or three weeks each year. This draft continued well into the 1960s. By the 1970s, they were having attendance problems during Shabbat services. The board decided to institute a new draft system: members with last names beginning with A-F were expected to attend a service during the first weekend of the month; those with names beginning with letters G-L were supposed to attend a service during the second weekend, and so on.

These attendance problems were a product of a shrinking membership. While it was once a large congregation, by 1999, only about 100 families were members of Agudath Achim. Shreveport’s Reform congregation, B’nai Zion, experienced a similar decline during the last decades of the 20th century, and the two congregations merged their religious schools in the early 21st century. As of 2023 Agudath Achim no longer belongs to the Conservative Movement and does not employ a full-time rabbi. Nevertheless, the congregants of Agudath Achim continue to preserve a vibrant and visible Jewish presence in the city of Shreveport.

By 1946, the congregation began to have a hard time finding ten men to make up the daily minyan, so they instituted a draft whereby other members would be assigned each week to make the minyan. Members were promised that they would not be drafted for more than two or three weeks each year. This draft continued well into the 1960s. By the 1970s, they were having attendance problems during Shabbat services. The board decided to institute a new draft system: members with last names beginning with A-F were expected to attend a service during the first weekend of the month; those with names beginning with letters G-L were supposed to attend a service during the second weekend, and so on.

These attendance problems were a product of a shrinking membership. While it was once a large congregation, by 1999, only about 100 families were members of Agudath Achim. Shreveport’s Reform congregation, B’nai Zion, experienced a similar decline during the last decades of the 20th century, and the two congregations merged their religious schools in the early 21st century. As of 2023 Agudath Achim no longer belongs to the Conservative Movement and does not employ a full-time rabbi. Nevertheless, the congregants of Agudath Achim continue to preserve a vibrant and visible Jewish presence in the city of Shreveport.