Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Aberdeen, Mississippi

Overview >> Mississippi >> Aberdeen

Overview

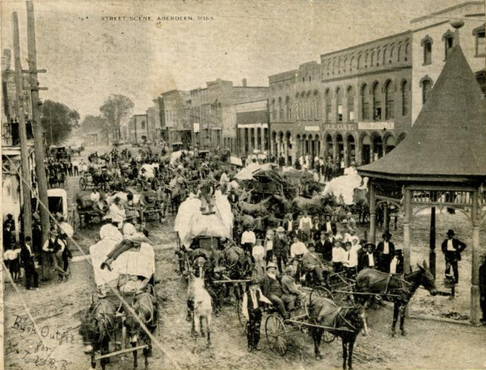

"Street scene, Aberdeen, Miss.," early 20th century.

Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Cooper Postcard Collection.

"Street scene, Aberdeen, Miss.," early 20th century.

Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Cooper Postcard Collection.

Aberdeen, located on the Tombigbee River in Northeast Mississippi, is the seat of Monroe County. Humans have inhabited the area for approximately 10,000 years, and Monroe County is home to the oldest archaeological findings in the state. When European settlers arrived, the territory was home to the Chickasaw Nation, and it remained so until Removal in the 1830s . After the state of Mississippi established Monroe County in 1821, the area attracted increasing numbers of white settlers, who imported enslaved Black workers to work in agricultural labor camps.

As the local population grew in the mid-19th century, a handful of Jewish families found their way to Aberdeen and surrounding towns, where they made their livings primarily in trade. While Aberdeen’s small Jewish community never established its own congregation or other Jewish institutions, a number of these families established successful businesses and diversified their interests to include real estate, farming, and wholesale businesses. By 1904 a number of Aberdeen Jews joined B’nai Israel in Columbus, and they played a significant role in the congregation for much of the 20th century. The local Jewish population entered a phase of decline by the mid-century, however, and the last of the longstanding Jewish families left Aberdeen in 1996.

As the local population grew in the mid-19th century, a handful of Jewish families found their way to Aberdeen and surrounding towns, where they made their livings primarily in trade. While Aberdeen’s small Jewish community never established its own congregation or other Jewish institutions, a number of these families established successful businesses and diversified their interests to include real estate, farming, and wholesale businesses. By 1904 a number of Aberdeen Jews joined B’nai Israel in Columbus, and they played a significant role in the congregation for much of the 20th century. The local Jewish population entered a phase of decline by the mid-century, however, and the last of the longstanding Jewish families left Aberdeen in 1996.

The Mid-to-Late 19th Century

The population of Monroe County more than doubled between 1840 and 1860, and this growth attracted the area’s first known Jewish residents. Marks Weiler, a native of Bavaria, lived near Aberdeen by the time of the 1850 U.S. Census. Ten years later he was a well established merchant in the town and had married a fellow Bavarian, Dorothy Haas Weiler. The couple had two children at that time (out of an eventual six), and the 1860 census indicates that they enslaved one Black worker, a 15-year-old girl. The household also included Dorothy’s brother, Samuel Haas, and two American-born nephews from the Weiler side of the family, Abram (Abe) and Leopold Kraus. Samuel Haas became a partner in the store before the Civil War, at which point he served four years in the Confederate Army. Afterward, the Kraus brothers joined the business, which took the name Weiler, Haas & Kraus. Samuel Kraus also bought at least 18 farms by the end of the 1870s. In 1880 the four owners sold their mercantile business to brothers Anton and Morris Stern (likely relatives of Abe and Leopold Kraus), and they relocated to New York City. When Samuel Haas died in 1920, the local paper carried news of his death and recalled his “enviable record for business integrity and upright enterprising citizenship.”

By the time that the Weiler, Haas, and Kraus families departed, a number of additional Jewish families had become prominent local figures. Another pair of German-Jewish brothers, Morris and Jacob (Jake) Gattman, arrived by 1855, along with a young nephew, Myer Gattman. Like Samuel Haas, Jake Gattman served in the Confederate Army. He and his brother operated separate retail businesses for a time before uniting their businesses after the Civil War. They become successful enough that they opened the Gattman & Co. bank in 1874, which included Myer as an owner. Jacob and Morris proved especially popular in town, and their business interests included farming and real estate. In the mid-1880s the Gattman’s invested in a development project about 20 miles east of Aberdeen, near the Alabama border, and the newly established town, Gattman, was named for the family. Within a few years, however, they were bankrupt, after Myer Gattman allegedly lost most of the bank’s deposits in cotton futures speculation. When the bank failed in 1888 Myer fled town and Jacob attempted suicide. The entire family relocated within a short time.

Most Jewish migrants to the Aberdeen area began their careers in retail. Abe and Julius Rubel, for example, came from Germany to the United States and opened a store in Aberdeen in 1890. Newspaper editor and native Kentuckian Sydney Jonas was an exception to the general trend; he first came to the area as a civil engineer, and after reaching the rank of major in the Confederate Army he became the longtime publisher and editor of the weekly Aberdeen Examiner. Jonas also gained recognition for his poem “The Confederate Note,” an early expression of “Lost Cause” ideology. Although Jonas came from a Jewish family, it is not apparent that he maintained Jewish practice in adulthood, and a Methodist pastor officiated his funeral. Following Jonas’s death in 1915, the local chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy erected a memorial in his honor.

By the time that the Weiler, Haas, and Kraus families departed, a number of additional Jewish families had become prominent local figures. Another pair of German-Jewish brothers, Morris and Jacob (Jake) Gattman, arrived by 1855, along with a young nephew, Myer Gattman. Like Samuel Haas, Jake Gattman served in the Confederate Army. He and his brother operated separate retail businesses for a time before uniting their businesses after the Civil War. They become successful enough that they opened the Gattman & Co. bank in 1874, which included Myer as an owner. Jacob and Morris proved especially popular in town, and their business interests included farming and real estate. In the mid-1880s the Gattman’s invested in a development project about 20 miles east of Aberdeen, near the Alabama border, and the newly established town, Gattman, was named for the family. Within a few years, however, they were bankrupt, after Myer Gattman allegedly lost most of the bank’s deposits in cotton futures speculation. When the bank failed in 1888 Myer fled town and Jacob attempted suicide. The entire family relocated within a short time.

Most Jewish migrants to the Aberdeen area began their careers in retail. Abe and Julius Rubel, for example, came from Germany to the United States and opened a store in Aberdeen in 1890. Newspaper editor and native Kentuckian Sydney Jonas was an exception to the general trend; he first came to the area as a civil engineer, and after reaching the rank of major in the Confederate Army he became the longtime publisher and editor of the weekly Aberdeen Examiner. Jonas also gained recognition for his poem “The Confederate Note,” an early expression of “Lost Cause” ideology. Although Jonas came from a Jewish family, it is not apparent that he maintained Jewish practice in adulthood, and a Methodist pastor officiated his funeral. Following Jonas’s death in 1915, the local chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy erected a memorial in his honor.

The 20th Century

A handful of Jewish families continued to make their homes in Aberdeen during the 20th century. Descendants of the Rubel family continued to live in the area, and they had connections to relatives in nearby Okolona and Columbus (where Aberdeen Jews attended services and religious school), as well as Corinth, Mississippi, near the Tennessee border. In the late 1930s the Rubel family aided German relatives in escaping Nazi Germany. Else and Rudolph Rubel arrived with their children, Ruth and Werner, in 1938, and they initially lived with Rudolph’s brother Jake. Other local Jewish families, including the Bergmans, Solomons, and Lanskys, helped the newcomers to acclimate.

As the 20th century continued, the local Jewish population declined, as it did in nearby small towns. The Lasky’s, who owned retail businesses in Aberdeen for more than a century, were the last Jewish family in town. In the 1960s Bernard Lasky operated Lasky’s, which specialized in women’s and children’s clothing. Lasky, a local native, was popular in town and served as the president of the Rotary Club in the 1950s. His wife Dorothy was also a popular figure in town. In addition to local civic and social organizations, they participated in B’nai Israel congregation in Columbus, where Bernard served as president. Despite the couple’s popularity, they ran afoul of local segregationists during the 1960s. After local Black activists organized a boycott of white-owned downtown businesses to protest the police department’s use of Confederate flag patches on their uniforms, Bernard suggested that the city meet the boycotters’ demand in order to resume normal business. As a result, segregationists burned a cross in front of the Lasky’s home. Despite the volatility of the era, the family continued to do business in Aberdeen for decades. When Bernard retired around 1990 his son Paul took over the store, which had locations in Aberdeen and West Point. When Paul closed the business in 1996 and moved to Columbus, his departure marked the end of Aberdeen’s Jewish community.

As the 20th century continued, the local Jewish population declined, as it did in nearby small towns. The Lasky’s, who owned retail businesses in Aberdeen for more than a century, were the last Jewish family in town. In the 1960s Bernard Lasky operated Lasky’s, which specialized in women’s and children’s clothing. Lasky, a local native, was popular in town and served as the president of the Rotary Club in the 1950s. His wife Dorothy was also a popular figure in town. In addition to local civic and social organizations, they participated in B’nai Israel congregation in Columbus, where Bernard served as president. Despite the couple’s popularity, they ran afoul of local segregationists during the 1960s. After local Black activists organized a boycott of white-owned downtown businesses to protest the police department’s use of Confederate flag patches on their uniforms, Bernard suggested that the city meet the boycotters’ demand in order to resume normal business. As a result, segregationists burned a cross in front of the Lasky’s home. Despite the volatility of the era, the family continued to do business in Aberdeen for decades. When Bernard retired around 1990 his son Paul took over the store, which had locations in Aberdeen and West Point. When Paul closed the business in 1996 and moved to Columbus, his departure marked the end of Aberdeen’s Jewish community.

Updated August 2022

Selected Bibliography

Paul Lasky, oral history interview, July 10, 2011, Institute of Southern Jewish Life Oral History Collection.

Robert N. Rosen, The Jewish Confederates, (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2000).

Paul Lasky, oral history interview, July 10, 2011, Institute of Southern Jewish Life Oral History Collection.

Robert N. Rosen, The Jewish Confederates, (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2000).