Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Grand Gulf, Mississippi

Overview >> Mississippi >> Grand Gulf

Overview

Located below the juncture of the Mississippi and Big Black Rivers in the northwest corner of Claiborne County, Grand Gulf was once a bustling river port. French settlers established the town in the early 18th century. The area passed to United States control in 1798, and the town emerged as a trading hub for the local agricultural economy in subsequent decades. By 1860, Claiborne County was home to approximately sixteen thousand people, two-thirds of whom were enslaved Black workers who primarily labored on large cotton plantations. Much of the area’s cotton passed through Grand Gulf on its way to textile mills in the urban North. A rail line connected the port town to the larger market town of Port Gibson in the 1830s, and in a typical week, over 20 steamboats would stop in Grand Gulf to trade and to restock. These boats carried not only goods but also new arrivals, including young Jewish merchants. Jews lived in Grand Gulf in the 19th century until the eventual decline and demise of the town.

Jewish Grand Gulf

Jewish peddlers likely settled in Grand Gulf after travels on the Mississippi River, attracted by business opportunities away from the larger port of New Orleans. J.L. and H.P. Levy established a business there by 1838. Census records do not indicate that J.L. Levy lived there, but H.P. Levy remained in Grand Gulf at least until 1850. He was a native of South Carolina and made his living as a merchant. The records also show that Levy household enslaved five Black women and girls in 1840 and three in 1850. The presence of a small number of enslaved workers at the Levy home was consistent with patterns among southern Jews at the time, who tended to use slave labor for domestic work or assistance in a shop and rarely owned large plantations.

As in other small towns, Jewish businesses in Grand Gulf specialized in dry goods and groceries. One such enterprise was Reynolds, Abraham and Company. Although no record exists of a Jewish congregation in Grand Gulf, Jews typically involved themselves in the Jewish communities of neighboring towns. Grand Gulf Jews had family connections to coreligionists in Port Gibson, Lorman, Fayette, and Natchez, and they helped to start Congregation Gemiluth Chassed in Port Gibson in 1859.

While Grand Gulf showed a great deal of promise in the 1830s and 1840s, multiple events eventually led to its demise. Between 1840 and 1860, several bouts of yellow fever afflicted the Claiborne County area and decimated Grand Gulf’s population. In the 1850s, not only did a tornado destroy some of the town, but the Mississippi River began to change course, which destroyed much of the port town’s business district. While natural disasters and disease reduced the population of Grand Gulf to a few hundred individuals, the town’s end came about during the Civil War. During 1862 and 1863, the Union and Confederate militaries fought for control of the area, which held strategic value in the contest over the control of the Mississippi River. Civilians fled the town, and fire destroyed some or all of the remaining buildings. Some Jews may have lived in Grand Gulf or the vicinity in the postwar years, but the town never recovered and was ultimately abandoned.

Among the Confederate troops who fought at Grand Gulf was a Jewish servicemember, Samuel L. Benjamin. An immigrant from Alsace-Lorraine, Benjamin had settled in New Orleans and later in Natchez, where he entered the Confederate Army in 1862. Hismilitary duties ended a year later due to his capture at Grand Gulf.

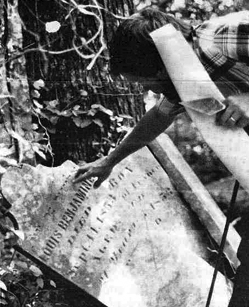

A Discovery of Jewish History in Grand Gulf

More than a century after the abandonment of Grand Gulf, new evidence of the town’s Jewish past resurfaced. In 1988, researchers found nine gravestones partially inscribed in Hebrew, which date back as early as 1853. These nine Jews were French and German immigrants who likely intended to settle elsewhere, but who ended up dying in Grand Gulf, probably due to yellow fever outbreaks. The burial site’s century of obscurity, like the abandoned port town’s brief period of Jewish settlement, reflect the transience of Jewish life in the 19th-century United States. The Grand Gulf Military Monument Park, where the Jewish grave sites are preserved, is the only vestige of the once-prosperous town.