Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Chickasha, Oklahoma

Chickasha: Historical Overview

Named for the Chickasaw Indians in the language of the Choctaw tribe, Chickasha was established in 1892 when the Chicago, Rock Island, and Pacific Railroad built a line through the area. Chickasha quickly became the area’s major exporting point for cattle and crops, which are still among its main industries. Ten years later, the growing town was formally incorporated, and soon afterward Oklahoma joined the United States. By the time Oklahoma became a state in 1907, downtown Chickasha had already been shaped by a small but influential Jewish population.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Chickasha

Early Settlers

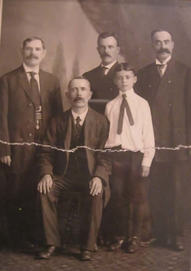

As immigrants from Russia, the Jews of Chickasha followed a path similar to their contemporaries throughout the South, opening shops and founding community organizations. In the years just before statehood, Abraham Belk and his wife Sadie moved to Chicaksha and opened a junk business. Herman Kohn owned a dry goods store in town by 1906, while Benjamin Lubman had a jewelry store. Lubman, a Russian native, moved to Chickasha from Kansas City in 1902 to open his jewelry store, which also sold optical goods and gentleman’s furnishings. Leopold Wohlgemuth, a native of Germany, moved to Chickasha from Illinois to open the People’s Store, a general dry goods store, in the first decade of the 20th century. His son-in-law, Louis Erlich, co-owned the business while his daughter Florence worked as a clerk. In 1910, the two families lived together. By 1930, the store was gone, and the Erlich and Wohlgemuth families had left Chickasha.

By far the most prominent and long lasting Jewish business in Chickasha was the Dixie Store, owned by friends and distant cousins Charles I. Miller and Ben Levine. Opened in 1919 on the premises of the recently closed Dugan Department Store, the Dixie was one of six department stores owned by the Miller Family around southwestern Oklahoma.

As immigrants from Russia, the Jews of Chickasha followed a path similar to their contemporaries throughout the South, opening shops and founding community organizations. In the years just before statehood, Abraham Belk and his wife Sadie moved to Chicaksha and opened a junk business. Herman Kohn owned a dry goods store in town by 1906, while Benjamin Lubman had a jewelry store. Lubman, a Russian native, moved to Chickasha from Kansas City in 1902 to open his jewelry store, which also sold optical goods and gentleman’s furnishings. Leopold Wohlgemuth, a native of Germany, moved to Chickasha from Illinois to open the People’s Store, a general dry goods store, in the first decade of the 20th century. His son-in-law, Louis Erlich, co-owned the business while his daughter Florence worked as a clerk. In 1910, the two families lived together. By 1930, the store was gone, and the Erlich and Wohlgemuth families had left Chickasha.

By far the most prominent and long lasting Jewish business in Chickasha was the Dixie Store, owned by friends and distant cousins Charles I. Miller and Ben Levine. Opened in 1919 on the premises of the recently closed Dugan Department Store, the Dixie was one of six department stores owned by the Miller Family around southwestern Oklahoma.

A newspaper advertisement from March of that year read “If you want nifty stuff, wait till the Dixie opens up.” As Eleanor Miller, the daughter-in-law of Charles Miller, put it, “every cousin that came over from the old country had a store”—and department store dynasties overlapped; Ben Levine’s wife Henrietta came from the Katz family of Ada, who had a chain of family stores of their own. The Dixie in Chickasha, which lasted the longest, was not like the other family stores. Charles and Ben became icons in the Chickasha community, running a newspaper ad for their department store every day for over 50 years. They hosted yearly Dixie Days during which Charles, buyer of boys’ and men’s clothing, had shoes and live turkeys thrown from the store windows as a promotion. Ben, who bought ladies’ wear and piece goods, supplied Chickasha with rationed hosiery during World War II, and the long lines that snaked from the store were evidence both of the community’s dependence on the Dixie and Ben and Charlie’s commitment to their customers.

|

Organized Jewish Life in Chickasha

By the late teens, Chickasha’s Jewish population appears to have reached its peak; according to the 1919 American Jewish Year Book, the small town had approximately 125 Jews. With this growth in the Jewish community, Chickasha Jews founded the short-lived B’nai Abraham congregation in 1915. By 1919, Samuel Goldsmith, a Polish-born dry goods merchant in town, was leading services for the congregation. Since these services were in Hebrew, the congregation was most likely Orthodox. L. Gasper was president of the congregation in 1919 while Louis Erlich was the secretary-treasurer. They would bring in visiting spiritual leaders to lead High Holiday services. In 1919, David Harris, leader of the Orthodox synagogue in Oklahoma City, led Rosh Hashanah services for B’nai Abraham, which were held at the local Masonic Temple since there was no synagogue in town. The group continued to meet for High Holiday services at the Masonic Temple in the early 1920s, though the congregation soon became inactive. It’s unclear precisely when B’nai Abraham disbanded, but the congregation had been largely forgotten by local Jewish residents by the 1950s. Chickasha Jews did later establish the Southwest Oklahoma Lodge of B’nai B’rith, which also had members in Anadarko and Lawton. |

Multimedia: Originally from St. Louis, Eleanor Miller moved to Chickasha in 1958 after marrying her husband Bill. In this clip from her 2012 interview with the ISJL Oral History Program, she talks about raising Jewish children and maintaining a kosher kitchen in small-town Oklahoma.

|

Aaron Slutzky, a young Polish Jew, came through Ellis Island in 1920. He was planning to meet his father, who had immigrated ten years earlier, in Shawnee, Oklahoma. Aaron’s father had first settled in Oklahoma City. A farmer by trade and trained as a cantor, Aaron’s father was informed by the Oklahoma City rabbi that the congregation in Shawnee needed a cantor, and that a farmer would have few work options in a city. After joining his father in Shawnee and attending high school, Aaron obtained a degree in Pharmacology from Oklahoma State University. Aaron heard about a pharmacy for sale in Chickasha and bought it, living above the shop for 35 years. Although there was no longer an active congregation in Chickasha, Slutzky was active in the Jewish community, serving as treasurer of the Southwest Oklahoma B’nai B’rith lodge in 1942.

Although they had no formal congregation or synagogue, some Chickasha Jews worked to maintain traditional religious practices. Most traveled to Oklahoma City, 40 miles away, for services, usually at the more traditional Emanuel Synagogue. Bill Miller, Charles’ son, traveled all the way to St. Louis in search of a Jewish wife. There he met and married Eleanor Bleiweiss. Back in Chickasha, Bill and Eleanor kept a kosher home, having kosher meat shipped in from Chicago, Denver, or Saint Louis.

Although they had no formal congregation or synagogue, some Chickasha Jews worked to maintain traditional religious practices. Most traveled to Oklahoma City, 40 miles away, for services, usually at the more traditional Emanuel Synagogue. Bill Miller, Charles’ son, traveled all the way to St. Louis in search of a Jewish wife. There he met and married Eleanor Bleiweiss. Back in Chickasha, Bill and Eleanor kept a kosher home, having kosher meat shipped in from Chicago, Denver, or Saint Louis.

A Declining Community

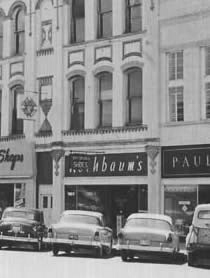

By 1937, 58 Jews lived in Chickasha, though this number would continue to decline during the post-war years. The late 1950s and 1960s saw the closing of many Jewish-owned businesses, including the Singer’s scrap metal business, the Rothbaum Shoe Store, and William Magid’s jewelry shop. The Chickasha B’nai B’rith chapter, which had been quite active during the war, also closed around this time. Eleanor and Bill Miller, who had been active members of the organization, could no longer devote their Sunday afternoons to meetings; they needed the time to drive their children to Sunday school in Oklahoma City. By the 1970s, the Millers were the only Jewish family with children still living in Chickasha. In subsequent years, Eleanor reports, Chickasha Jewish life was mostly social, with most local Jews driving to Oklahoma City for services.

Despite this decline, the Dixie remained in business. Bill Miller had started working at the store when he returned from the army in the mid-1950s. Ben Levine’s son, Stanley, had been working there since college, and he and Bill took over the store when Ben died and Charlie Miller retired. Bill and Stanley ran the business for the next several decades, with Eleanor Miller also working in the store. The Millers were very active in the local community. Bill served as president of the Chamber of Commerce and the Rotary Club while Eleanor was named Businesswoman of the Year by the Chamber of Commerce. Finally, on December 17, 1994, “a day that will live in infamy,” according to Eleanor Miller, they decided to close the Dixie Store. The partners felt that they were simply too old to keep running the business, and none of their children wanted to take it over.

By 1937, 58 Jews lived in Chickasha, though this number would continue to decline during the post-war years. The late 1950s and 1960s saw the closing of many Jewish-owned businesses, including the Singer’s scrap metal business, the Rothbaum Shoe Store, and William Magid’s jewelry shop. The Chickasha B’nai B’rith chapter, which had been quite active during the war, also closed around this time. Eleanor and Bill Miller, who had been active members of the organization, could no longer devote their Sunday afternoons to meetings; they needed the time to drive their children to Sunday school in Oklahoma City. By the 1970s, the Millers were the only Jewish family with children still living in Chickasha. In subsequent years, Eleanor reports, Chickasha Jewish life was mostly social, with most local Jews driving to Oklahoma City for services.

Despite this decline, the Dixie remained in business. Bill Miller had started working at the store when he returned from the army in the mid-1950s. Ben Levine’s son, Stanley, had been working there since college, and he and Bill took over the store when Ben died and Charlie Miller retired. Bill and Stanley ran the business for the next several decades, with Eleanor Miller also working in the store. The Millers were very active in the local community. Bill served as president of the Chamber of Commerce and the Rotary Club while Eleanor was named Businesswoman of the Year by the Chamber of Commerce. Finally, on December 17, 1994, “a day that will live in infamy,” according to Eleanor Miller, they decided to close the Dixie Store. The partners felt that they were simply too old to keep running the business, and none of their children wanted to take it over.

The Jewish Community in Chickasha Today

Over the years, the Jewish community of Chickasha has dwindled. Many passed away or moved to Oklahoma City. After Bill Miller died in 2011, his wife Eleanor became the last Jew in town. She still keeps kosher, though she doesn’t eat meat as much as she used to. When she wants some, she makes the three-and-a-half-hour drive to Dallas. A local auditorium bears her name. She still holds Passover seders at her home, which attract many of her Christian friends. Today, there is no building marking the synagogue she arrived too late to be a part of, and no Jewish cemetery where she can visit the dead. Nevertheless, the Dixie Store remains a fixture of downtown Chickasha, serving as the home of the Grady County Historical Museum. One day, the only vestiges of this once flourishing Jewish community will reside within its walls.