Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Guthrie, Oklahoma

Guthrie: Historical Overview

Downtown Guthrie, c. 1895.

Downtown Guthrie, c. 1895. Photo courtesy of Oklahoma Territorial Museum.

It would be an exaggeration to say that Guthrie, Oklahoma, popped up overnight, but only because it happened in the daytime. Between noon and 6 pm on April 22, 1889, about 10,000 people descended in a “land run” on the dusty railroad stop, which congress had ruled eligible for settlement only weeks earlier, and which by the end of the day had become the largest city in the Oklahoma territory. The thousands of tents hastily pitched by the ‘89ers broke up the long view to the horizon over the flat Oklahoma plains. One land runner, Moses Weinberger, made his tent from the canvas top of the covered wagon in which he had followed pioneer trails to Kansas several years before, now the first Jew to arrive in Guthrie. Beginning with Weiberger's arrival, Jews would play a part in the development of Guthrie.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Guthrie

Moses Weinberger (center) in front of his saloon.

Moses Weinberger (center) in front of his saloon. Photo courtesy of Oklahoma Territorial Museum.

Moses Weinberger

Arriving by train to Guthrie was only the most recent leg of a journey that had begun when Moses Weinberger was 18 years old. As soon as he reached adulthood, Weinberger left his Orthodox Jewish parents’ 32-acre farm in rural Hungary and took a steamship to America. After three years of working as a butcher boy in New York, Weinberger had saved enough money to visit his parents back in Europe, but when he got there he was conscripted into the Austrian army. After six months of good behavior while stationed in Vienna, Weinberger went AWOL on his furlough, catching a ship back to New York from a port in Germany. When he arrived back in the U.S., he started the naturalization process immediately.

Once he had his citizenship, Weinberger followed the trails of wagon trains west to Wichita, Kansas, where he got involved in wholesale fruit shipping. It was from Kansas, over acres of prairie, that Weinberger travelled by rail to Guthrie aboard the second-ever passenger train to enter Oklahoma territory. By nightfall on April 22, 1889, the new American had secured a plot in the land run. The process for formalizing a claim involved standing in line at the land office, which was itself only a tent. Because leaving the line meant losing a spot, the ‘89ers, who were nearly all men, stood for hours, often without anything to eat.

With an immigrant’s ingenuity, Weinberger wired the Bryan Brothers Fruit Company, where he’d worked back in Wichita, and had them express ship a huge load of bananas to Guthrie. The next morning he picked them up at the train station, and proceeded to peddle the fruit up and down the land-claim line. Weinberger’s banana sales were so successful that he soon purchased a cart and mules and began peddling fruit in the booming town. In 1890, Weinberger bought a house, and brought his family down from Wichita. He soon deemed Guthrie too wild for his wife and children, so he staked a new claim northwest of town, in Chandler, and settled them there. While pursuing business interests in Guthrie, Weinberger rode out to see his family about once a week.

If Guthrie was a lawless Wild West town, full of guns and brothels, Chandler’s muddy roads were treacherous and riddled with rattlesnakes. The lack of plumbing and sanitation in the countryside meant that illness spread quickly, and after several of Weinberger’s children contracted malaria, he moved them back to Guthrie, where running water, electricity, and a public school system had all been installed by the end of 1889. Around the same time, a number of U.S. troops were sent to keep order in the unincorporated town, which at the time was under the jurisdiction of four different provisional governments. The short story writer O. Henry characterized the bursting energy of the era, writing that “when the Oklahoma country was in the middle of its first bloom, Guthrie was rising in the middle of it like a lump of self-rising dough.”

In such an environment, an ambitious man like Moses Weinberger couldn’t help but prosper, even with a family to take care of. By erecting a cardboard house and leasing out rooms to real estate agents, Moses both promoted and capitalized on Guthrie’s burgeoning commerce. After opening a permanent fruit stand on West Oklahoma Street, Weinberger obtained the first liquor license in Guthrie and opened its first legal saloon. He called it “The Same Old Moses,” which is how he introduced himself to old friends from Kansas. Within 60 days of the saloon’s opening, 44 others had opened up in Guthrie. The flagrant alcohol consumption in Guthrie offended famous prohibitionist Carry Nation, who settled there in order to advocate for the abolition of “demon rum,” and to shame those who sold and consumed it. In a publicity stunt, Weinberger invited her to speak in his saloon, provided that she not wield the infamous bar-bashing axe after which her temperance newsletter, The Hatchet, was named. Carry kept her promise only until the end of her speech, at which point she hacked into Moses’ mahogany bar, removing a chunk of it. She was promptly thrown from the saloon, and the patrons of The Same Old Moses adopted the habit of banging their empty beer mugs on the busted bar when they wanted another round. Weinberger, meanwhile, hung a sign outside the saloon reading “All nations welcomed except Carry,” and over the course of the next decade opened six more saloons in town. The best known of these was the White Star Tavern, which was run by his sons David and Jacob, while his son Harry operated a cigar shop.

Arriving by train to Guthrie was only the most recent leg of a journey that had begun when Moses Weinberger was 18 years old. As soon as he reached adulthood, Weinberger left his Orthodox Jewish parents’ 32-acre farm in rural Hungary and took a steamship to America. After three years of working as a butcher boy in New York, Weinberger had saved enough money to visit his parents back in Europe, but when he got there he was conscripted into the Austrian army. After six months of good behavior while stationed in Vienna, Weinberger went AWOL on his furlough, catching a ship back to New York from a port in Germany. When he arrived back in the U.S., he started the naturalization process immediately.

Once he had his citizenship, Weinberger followed the trails of wagon trains west to Wichita, Kansas, where he got involved in wholesale fruit shipping. It was from Kansas, over acres of prairie, that Weinberger travelled by rail to Guthrie aboard the second-ever passenger train to enter Oklahoma territory. By nightfall on April 22, 1889, the new American had secured a plot in the land run. The process for formalizing a claim involved standing in line at the land office, which was itself only a tent. Because leaving the line meant losing a spot, the ‘89ers, who were nearly all men, stood for hours, often without anything to eat.

With an immigrant’s ingenuity, Weinberger wired the Bryan Brothers Fruit Company, where he’d worked back in Wichita, and had them express ship a huge load of bananas to Guthrie. The next morning he picked them up at the train station, and proceeded to peddle the fruit up and down the land-claim line. Weinberger’s banana sales were so successful that he soon purchased a cart and mules and began peddling fruit in the booming town. In 1890, Weinberger bought a house, and brought his family down from Wichita. He soon deemed Guthrie too wild for his wife and children, so he staked a new claim northwest of town, in Chandler, and settled them there. While pursuing business interests in Guthrie, Weinberger rode out to see his family about once a week.

If Guthrie was a lawless Wild West town, full of guns and brothels, Chandler’s muddy roads were treacherous and riddled with rattlesnakes. The lack of plumbing and sanitation in the countryside meant that illness spread quickly, and after several of Weinberger’s children contracted malaria, he moved them back to Guthrie, where running water, electricity, and a public school system had all been installed by the end of 1889. Around the same time, a number of U.S. troops were sent to keep order in the unincorporated town, which at the time was under the jurisdiction of four different provisional governments. The short story writer O. Henry characterized the bursting energy of the era, writing that “when the Oklahoma country was in the middle of its first bloom, Guthrie was rising in the middle of it like a lump of self-rising dough.”

In such an environment, an ambitious man like Moses Weinberger couldn’t help but prosper, even with a family to take care of. By erecting a cardboard house and leasing out rooms to real estate agents, Moses both promoted and capitalized on Guthrie’s burgeoning commerce. After opening a permanent fruit stand on West Oklahoma Street, Weinberger obtained the first liquor license in Guthrie and opened its first legal saloon. He called it “The Same Old Moses,” which is how he introduced himself to old friends from Kansas. Within 60 days of the saloon’s opening, 44 others had opened up in Guthrie. The flagrant alcohol consumption in Guthrie offended famous prohibitionist Carry Nation, who settled there in order to advocate for the abolition of “demon rum,” and to shame those who sold and consumed it. In a publicity stunt, Weinberger invited her to speak in his saloon, provided that she not wield the infamous bar-bashing axe after which her temperance newsletter, The Hatchet, was named. Carry kept her promise only until the end of her speech, at which point she hacked into Moses’ mahogany bar, removing a chunk of it. She was promptly thrown from the saloon, and the patrons of The Same Old Moses adopted the habit of banging their empty beer mugs on the busted bar when they wanted another round. Weinberger, meanwhile, hung a sign outside the saloon reading “All nations welcomed except Carry,” and over the course of the next decade opened six more saloons in town. The best known of these was the White Star Tavern, which was run by his sons David and Jacob, while his son Harry operated a cigar shop.

Leo Meyer

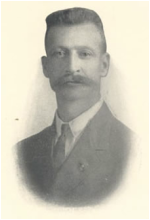

Leo Meyer

A Community Forms

After Guthrie was named the capital of the Oklahoma Territory in 1890, other Jewish immigrants were drawn to the bustling city. By 1893, German-born Felix Adler had secured Oklahoma Territory’s first wholesale liquor license, and in the next year the Oklahoma Illustrated wrote that “[f]ew establishments in Guthrie have done a more profitable business…and few men have given more liberally toward building up the town than Felix Adler.” Guthrie’s downtown streets were lined with stores like H.L. Cohen’s tailor shop and Samuel Goldstein’s Goldstein & Sons ready-to-wear clothing. Leo Meyer moved to Guthrie in 1907 when he was appointed Assistant Secretary of State. He owned a local baseball team in Guthrie and became president of the Western Association baseball league in 1909. In 1910, Meyer was elected as State Auditor, though he would arouse controversy in Guthrie over his support for moving the state capital to Oklahoma City. According to a 1905 survey by the Industrial Removal Office in New York on “Conditions of Jewish Life in small American Cities,” there were only 11 Jewish families in Guthrie at the time. Despite their small numbers, the interests of the Jews were so tied to the interests of Guthrie as a whole that in the same year, the Guthrie Daily Leader devoted front page coverage to pogroms in Poland and anti-Semitic conflicts in Vienna.

After Guthrie was named the capital of the Oklahoma Territory in 1890, other Jewish immigrants were drawn to the bustling city. By 1893, German-born Felix Adler had secured Oklahoma Territory’s first wholesale liquor license, and in the next year the Oklahoma Illustrated wrote that “[f]ew establishments in Guthrie have done a more profitable business…and few men have given more liberally toward building up the town than Felix Adler.” Guthrie’s downtown streets were lined with stores like H.L. Cohen’s tailor shop and Samuel Goldstein’s Goldstein & Sons ready-to-wear clothing. Leo Meyer moved to Guthrie in 1907 when he was appointed Assistant Secretary of State. He owned a local baseball team in Guthrie and became president of the Western Association baseball league in 1909. In 1910, Meyer was elected as State Auditor, though he would arouse controversy in Guthrie over his support for moving the state capital to Oklahoma City. According to a 1905 survey by the Industrial Removal Office in New York on “Conditions of Jewish Life in small American Cities,” there were only 11 Jewish families in Guthrie at the time. Despite their small numbers, the interests of the Jews were so tied to the interests of Guthrie as a whole that in the same year, the Guthrie Daily Leader devoted front page coverage to pogroms in Poland and anti-Semitic conflicts in Vienna.

Organized Jewish Life in Guthrie

After having helped build up their town, Guthrie’s Jews became interested in establishing Jewish institutions. Some time after 1892, Moses Weinberger leased the third floor of the building that housed his saloon to the International Order of Odd Fellows, with the provision that Guthrie’s Jewish population be allowed to use the meeting hall for holiday services, though this arrangement lasted for only a few years. By 1900, Guthrie Jews were meeting together for High Holiday services. As Oklahoma moved toward statehood and with Guthrie as its capital, the city’s Jews anticipated a growing congregation that would need a permanent place of worship. Especially after Moses Weinberger’s discoveries of oil and mineral water, the Jewish community was flush, and it devised a plan to build a grand synagogue with its wealth. In 1906, the Muskogee Times-Democrat ran a story announcing that Guthrie’s “Hebrews recently effected an organization for the purpose of building a $25,000 temple, with Moses Weinberger as president, I.B. Levy treasurer and Morris [sic] Behr secretary.” The fledgling congregation had about ten families.

After having helped build up their town, Guthrie’s Jews became interested in establishing Jewish institutions. Some time after 1892, Moses Weinberger leased the third floor of the building that housed his saloon to the International Order of Odd Fellows, with the provision that Guthrie’s Jewish population be allowed to use the meeting hall for holiday services, though this arrangement lasted for only a few years. By 1900, Guthrie Jews were meeting together for High Holiday services. As Oklahoma moved toward statehood and with Guthrie as its capital, the city’s Jews anticipated a growing congregation that would need a permanent place of worship. Especially after Moses Weinberger’s discoveries of oil and mineral water, the Jewish community was flush, and it devised a plan to build a grand synagogue with its wealth. In 1906, the Muskogee Times-Democrat ran a story announcing that Guthrie’s “Hebrews recently effected an organization for the purpose of building a $25,000 temple, with Moses Weinberger as president, I.B. Levy treasurer and Morris [sic] Behr secretary.” The fledgling congregation had about ten families.

No Longer the Capital

Despite these grandiose synagogue plans, the temple was never built, and the congregation soon dissolved. In 1907, Oklahoma won statehood, and with it came prohibition. Weinberger, the saloon tycoon and a major source of funding for Guthrie’s Jewish community, had to sell his supplies and equipment, and he soon after went into the shipping and transport business. Then, three years later, Guthrie took another hit. In 1910, the state of Oklahoma held a vote to decide whether its capital would remain in Guthrie, or move to either Oklahoma City or Shawnee. Oklahoma City, which was by far the largest of the three cities, won the vote. The day after the vote, the Assistant Secretary of State, Leo Meyer, took the official state seal from the capitol building in Guthrie and moved it to Oklahoma City under cover of night.

The loss of the capital was devastating to Guthrie’s economy. The previously growing population stagnated at around 12,000, where it remains today. The city lost workers, investors, and priority on the rail lines, and many residents with the means to do so moved to nearby Oklahoma City. Two such defectors were charter members of the unrealized temple: Isaac Levy, proprietor of The Bee Hive Clothing House and first president of the Oklahoma State Bank; and Mortiz Behr of The Parisian. While Moses Weinberger remained in Guthrie, neither his transport business nor a subsequent ladies’ ready-to-wear shop were particularly successful.

Despite these grandiose synagogue plans, the temple was never built, and the congregation soon dissolved. In 1907, Oklahoma won statehood, and with it came prohibition. Weinberger, the saloon tycoon and a major source of funding for Guthrie’s Jewish community, had to sell his supplies and equipment, and he soon after went into the shipping and transport business. Then, three years later, Guthrie took another hit. In 1910, the state of Oklahoma held a vote to decide whether its capital would remain in Guthrie, or move to either Oklahoma City or Shawnee. Oklahoma City, which was by far the largest of the three cities, won the vote. The day after the vote, the Assistant Secretary of State, Leo Meyer, took the official state seal from the capitol building in Guthrie and moved it to Oklahoma City under cover of night.

The loss of the capital was devastating to Guthrie’s economy. The previously growing population stagnated at around 12,000, where it remains today. The city lost workers, investors, and priority on the rail lines, and many residents with the means to do so moved to nearby Oklahoma City. Two such defectors were charter members of the unrealized temple: Isaac Levy, proprietor of The Bee Hive Clothing House and first president of the Oklahoma State Bank; and Mortiz Behr of The Parisian. While Moses Weinberger remained in Guthrie, neither his transport business nor a subsequent ladies’ ready-to-wear shop were particularly successful.

Guthrie's newspaper scapegoats

Guthrie's newspaper scapegoats Jews for the loss of the state capital.

Levy and Behr’s relocation may have had as much to do with the concentration of Jewish life in the new state capital as anything else, but their perceived disloyalty to Guthrie made Jews a perfect scapegoat for the city’s rage at being slighted. Groundbreaking on the Oklahoma City capitol building did not begin until 1914, and in 1912 Guthrie revived the fight. On November 1, the Guthrie Daily Leader ran a front-page banner headline announcing that “Shylocks of Oklahoma City Have State by the Throat,” and the sub-header promised to reveal the “Unparalleled Conspiracy on the Part of Jews and Gentiles of a Rotten Town to Loot the State for Twenty-Five Years.” As Henry Tobias writes in The Jews of Oklahoma, the long piece that followed “stress[ed] the role of Jewish landlords and resort[ed] to parodied Yiddish accents to describe the dialogue of the miscreants…hop[ing] to destroy Oklahoma City’s hold by revealing a dishonest plot.” Isaac Levy and his brothers in particular were accused of having betrayed their city by contributing $10,000 to Oklahoma City’s capital campaign.

Rabbi Joseph Blatt of Temple B’nai Israel in Oklahoma City wrote powerfully in response to the Leader’s slander, defending the Levys and declaring the article a lie and “a disgrace to the civilization of our state.” He then appealed for support against religious prejudice which, if not contested, would become the norm. Rabbi Blatt’s bold defense of the Jews from the Leader’s attacks demonstrates the strong connection between the Jewish communities of Guthrie and Oklahoma City, where Isaac Levy ended up settling. The Leader’s efforts to blame the Jews and to reclaim Guthrie’s status as the state capital failed, and were soon forgotten.

Rabbi Joseph Blatt of Temple B’nai Israel in Oklahoma City wrote powerfully in response to the Leader’s slander, defending the Levys and declaring the article a lie and “a disgrace to the civilization of our state.” He then appealed for support against religious prejudice which, if not contested, would become the norm. Rabbi Blatt’s bold defense of the Jews from the Leader’s attacks demonstrates the strong connection between the Jewish communities of Guthrie and Oklahoma City, where Isaac Levy ended up settling. The Leader’s efforts to blame the Jews and to reclaim Guthrie’s status as the state capital failed, and were soon forgotten.

The Jewish Community in Guthrie Today

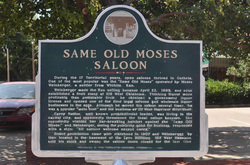

Historical Marker that stands at the

Historical Marker that stands at the location of Moses Weinberger's saloon.

The Jewish presence in Guthrie was forgotten almost as fast as the libelous article in the Leader. By 1937, only 17 Jews lived in town. Dreams of a congregation and a synagogue disappeared, as most of the town’s Jews had moved 30 miles south to Oklahoma City along with the state capital. The last record of Jewish life in Guthrie was in 1937, when Ruth E. Woon interviewed Moses Weinberger for the Indian-Pioneer History Project for Oklahoma, a WPA-sponsored oral history project that collected people’s stories about living in pre-statehood Oklahoma. Among the first to arrive in Guthrie, Weinberger refused to go anywhere else. In 1940, census records show him living on West Oklahoma Avenue with several of his children. He was 80 years old at the time, and he died later that year. He was buried in the local cemetery, next to his wife Rose and several of their children. Theirs are the only Jewish graves in Guthrie.

Moses Weinberger’s name can also be found on a plaque on Harrison Avenue where The Same Old Moses used to stand. The plaque tells the story of his confrontation with Carry Nation; their conflict, between debaucherous independence and regulated morality, typifies Oklahoma’s early history. Although its Jewish community is long gone, downtown Guthrie, restored to the way it once looked by preservationists in the 1980s, still evokes a time when the Jewish community was central to the city’s existence.

Moses Weinberger’s name can also be found on a plaque on Harrison Avenue where The Same Old Moses used to stand. The plaque tells the story of his confrontation with Carry Nation; their conflict, between debaucherous independence and regulated morality, typifies Oklahoma’s early history. Although its Jewish community is long gone, downtown Guthrie, restored to the way it once looked by preservationists in the 1980s, still evokes a time when the Jewish community was central to the city’s existence.