Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Okmulgee/Henryetta, Oklahoma

Okmulgee/Henryetta: Historical Overview

Okmulgee began as the capital of the Creek Nation, who built their seat of government there in 1868. It was not until the railroad was built through the town in 1900 that significant numbers of outside settlers moved to the area. By 1907, when Okmulgee was named the seat of Okmulgee County, 2,322 people lived in the growing town. The discovery of oil nearby that same year led to a huge boom in the local economy. By the mid-1920s, Okmulgee had five oil refineries and an estimated population of 35,000, making it the fourth largest city in Oklahoma. It was during these boom years that Jews first settled in Okmulgee.

Stories of the Jewish Communities in Okmulgee and Henryetta

1925 ad for Dave Franke's store

1925 ad for Dave Franke's store

Early Jewish Residents

Most early Jewish settlers in Okmulgee were merchants who did not stay in town very long. By 1909, Jacob Goldstein, A.J. Wigransky, and Harry Merson all owned clothing stores in Okmulgee. None of these merchants lived in Okmulgee in 1907, and all of them were gone by 1916, reflecting the temporary, unsettled nature of the early Jewish community.

As the city grew during the oil boom, a small group of Jewish families set down roots in Okmulgee. Born in Austria, Joseph Siegel came to the U.S. in 1905. By 1916, he and his wife Jennie had moved to Okmulgee, where they opened a store selling women’s and children’s clothing. Siegel’s remained in business until 1954, when Joseph died. Jennie Siegel had passed away 14 years earlier. Romanian-born Shy Mayer opened the Union Clothing Company in Okmulgee by 1916, which remained in business for several decades. Dave Franke, who was born in Virginia, opened a men’s clothing store in Okmulgee by 1918. In 1924, Franke created an annual award to go to a local citizen who had made a significant contribution to the city. Charles Peller opened Knight’s Ladies Wear by 1922, the height of the oil boom. The store remained in business until Peller died in 1952. Martin Brenner started a men’s wear and luggage store in Okmulgee in 1924 which remained in business for 32 years.

A few Okmulgee Jews got involved in the scrap metal and oil field supply business. Joe Erdberg, who came to the U.S. from Poland in 1905, moved to Okmulgee in 1919. By 1921, he had started his own oil field scrap metal company. Erdberg Junk & Supply remained in business for over 40 years. When Erdberg died in 1947, his wife Rosie took over the business. Later, their son Ollie ran Erdberg Junk & Supply, before closing it in 1963. Louis Stekoll, a native of Latvia, moved to Okmulgee in the 1920s and opened an oil well supply company. His two sons, Raymond and Marrion, also worked in the business.

Most early Jewish settlers in Okmulgee were merchants who did not stay in town very long. By 1909, Jacob Goldstein, A.J. Wigransky, and Harry Merson all owned clothing stores in Okmulgee. None of these merchants lived in Okmulgee in 1907, and all of them were gone by 1916, reflecting the temporary, unsettled nature of the early Jewish community.

As the city grew during the oil boom, a small group of Jewish families set down roots in Okmulgee. Born in Austria, Joseph Siegel came to the U.S. in 1905. By 1916, he and his wife Jennie had moved to Okmulgee, where they opened a store selling women’s and children’s clothing. Siegel’s remained in business until 1954, when Joseph died. Jennie Siegel had passed away 14 years earlier. Romanian-born Shy Mayer opened the Union Clothing Company in Okmulgee by 1916, which remained in business for several decades. Dave Franke, who was born in Virginia, opened a men’s clothing store in Okmulgee by 1918. In 1924, Franke created an annual award to go to a local citizen who had made a significant contribution to the city. Charles Peller opened Knight’s Ladies Wear by 1922, the height of the oil boom. The store remained in business until Peller died in 1952. Martin Brenner started a men’s wear and luggage store in Okmulgee in 1924 which remained in business for 32 years.

A few Okmulgee Jews got involved in the scrap metal and oil field supply business. Joe Erdberg, who came to the U.S. from Poland in 1905, moved to Okmulgee in 1919. By 1921, he had started his own oil field scrap metal company. Erdberg Junk & Supply remained in business for over 40 years. When Erdberg died in 1947, his wife Rosie took over the business. Later, their son Ollie ran Erdberg Junk & Supply, before closing it in 1963. Louis Stekoll, a native of Latvia, moved to Okmulgee in the 1920s and opened an oil well supply company. His two sons, Raymond and Marrion, also worked in the business.

Herman Sanditen

Herman Sanditen

Brothers Sam, Maurice, and Herman Sanditen left Lithuania for the United States, eventually settling in Okmulgee by the 1910s, where they also entered the scrap metal business. In 1918, they opened an automobile supply store called Oklahoma Tire and Supply Company, later known as OTASCO. In 1922, they opened a second location in Henryetta, and soon expanded across the state. In 1925, the Sanditens moved the business headquarters and their families to Tulsa, where they became important leaders of the local Jewish community.

In nearby Henryetta, a small number of Jews also concentrated in retail trade. Isaac Cutler, who lived in Henryetta by 1907, opened the Globe Store soon after arriving. During World War I, his brother-in-law, Max Reinberg, came to the area to run a branch of the clothing store in the small town of Kusa. When Cutler died of a heart condition in 1921, Reinberg moved to Henryetta to run the Globe Store. Reinberg stayed in Henryetta until his death in 1936, when the Globe Store closed. German-born Moses Kauffman lived in Ohio before moving to Henryetta and opening a clothing store by 1917. By 1938, his son Paul, who had married Isaac Cutler’s daughter Corrine, had joined him in the business; Paul later ran it himself. Kauffman’s Dry Goods finally closed in 1953 when Paul Kauffman died. In 1922, there were at least eight Jewish-owned stores in Henryetta. This number would soon drop; by 1938, only three Jewish-owned stores remained. The last such store in Henryetta was Ginsberg’s Department Store, which was run for decades by Leon Ginsberg until he sold the business in 1972. Oklahoma civil rights leader Clara Luper recalls that Ginsberg's was the only store in Henryetta that allowed blacks to try on shoes during the 1950s.

In nearby Henryetta, a small number of Jews also concentrated in retail trade. Isaac Cutler, who lived in Henryetta by 1907, opened the Globe Store soon after arriving. During World War I, his brother-in-law, Max Reinberg, came to the area to run a branch of the clothing store in the small town of Kusa. When Cutler died of a heart condition in 1921, Reinberg moved to Henryetta to run the Globe Store. Reinberg stayed in Henryetta until his death in 1936, when the Globe Store closed. German-born Moses Kauffman lived in Ohio before moving to Henryetta and opening a clothing store by 1917. By 1938, his son Paul, who had married Isaac Cutler’s daughter Corrine, had joined him in the business; Paul later ran it himself. Kauffman’s Dry Goods finally closed in 1953 when Paul Kauffman died. In 1922, there were at least eight Jewish-owned stores in Henryetta. This number would soon drop; by 1938, only three Jewish-owned stores remained. The last such store in Henryetta was Ginsberg’s Department Store, which was run for decades by Leon Ginsberg until he sold the business in 1972. Oklahoma civil rights leader Clara Luper recalls that Ginsberg's was the only store in Henryetta that allowed blacks to try on shoes during the 1950s.

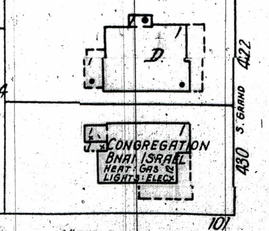

B'nai Israel on a 1949 map of Okmulgee

B'nai Israel on a 1949 map of Okmulgee

Organized Jewish Life in Okmulgee and Henryetta

By the second decade of the 20th century, the growing number of Jews in Okmulgee and Henryetta began to organize. Their first priority was to teach Judaism to their children. Sometime in the 1910s, women founded a Ladies Aid Society, which created and oversaw a religious school. Early attempts to create a formal congregation were unsuccessful. Gershon Fenster, who worked with the Sanditens, led services occasionally during these early years. Finally, in 1923, the Jews of Okmulgee and Henryetta came together to establish Congregation B’nai Israel. It was very small at first, numbering only 14 members. Charles Goodman was its first president. Though the congregation’s initial focus was on the religious school, Fenster, who had moved to Tulsa with OTASCO in 1925, would come back to Okmulgee to lead services once a month.

In early 1925, the members of B’nai Israel began raising money for a permanent home for the congregation. About 30 Jewish families lived in the area at the time. This effort began with women in the congregation serving a turkey dinner and then auctioning a number of gifts that had been donated. This event brought in $500 toward the cause, which inspired the members to continue the fundraising effort. Later in the year, they purchased a house on the corner of S. Grand and W. 10th streets, converting it into a small synagogue with a sanctuary and religious school rooms. Joseph Steinholtz, who owned a clothing store in Okmulgee, was B’nai Israel’s president when they acquired the synagogue. Elizabeth Brenner ran the Sunday school in 1925. The congregation never acquired land for a cemetery as most Jews in the area were buried 40 miles north in Tulsa. Okmulgee Jews also established a chapter of B’nai B’rith, which flourished during the early 1940s. Charles Peller was its president in 1942.

The members of B’nai Israel were relatively assimilated. Of nine officers and board members in 1925, four were born in the U.S. Five were immigrants, mostly from the Russian empire; one was from Austria. All of the immigrants had been in the U.S. for at least 19 years by the time they acquired the synagogue in 1925. Their average year of immigration was 1902. The group was young; their average age was just 36. Of the eight board members with occupations, three owned a retail store, while two were store clerks. Two owned oil field supply businesses, while one had a tailoring shop.

By the second decade of the 20th century, the growing number of Jews in Okmulgee and Henryetta began to organize. Their first priority was to teach Judaism to their children. Sometime in the 1910s, women founded a Ladies Aid Society, which created and oversaw a religious school. Early attempts to create a formal congregation were unsuccessful. Gershon Fenster, who worked with the Sanditens, led services occasionally during these early years. Finally, in 1923, the Jews of Okmulgee and Henryetta came together to establish Congregation B’nai Israel. It was very small at first, numbering only 14 members. Charles Goodman was its first president. Though the congregation’s initial focus was on the religious school, Fenster, who had moved to Tulsa with OTASCO in 1925, would come back to Okmulgee to lead services once a month.

In early 1925, the members of B’nai Israel began raising money for a permanent home for the congregation. About 30 Jewish families lived in the area at the time. This effort began with women in the congregation serving a turkey dinner and then auctioning a number of gifts that had been donated. This event brought in $500 toward the cause, which inspired the members to continue the fundraising effort. Later in the year, they purchased a house on the corner of S. Grand and W. 10th streets, converting it into a small synagogue with a sanctuary and religious school rooms. Joseph Steinholtz, who owned a clothing store in Okmulgee, was B’nai Israel’s president when they acquired the synagogue. Elizabeth Brenner ran the Sunday school in 1925. The congregation never acquired land for a cemetery as most Jews in the area were buried 40 miles north in Tulsa. Okmulgee Jews also established a chapter of B’nai B’rith, which flourished during the early 1940s. Charles Peller was its president in 1942.

The members of B’nai Israel were relatively assimilated. Of nine officers and board members in 1925, four were born in the U.S. Five were immigrants, mostly from the Russian empire; one was from Austria. All of the immigrants had been in the U.S. for at least 19 years by the time they acquired the synagogue in 1925. Their average year of immigration was 1902. The group was young; their average age was just 36. Of the eight board members with occupations, three owned a retail store, while two were store clerks. Two owned oil field supply businesses, while one had a tailoring shop.

B'nai Israel brought in an

B'nai Israel brought in an Orthodox rabbinic student in 1934 to lead

Rosh Hashanah services.

B'nai Israel brought in an Orthodox rabbinic student in 1934 to lead Rosh Hashanah services. B’nai Israel had a mix of Reform and traditional members. Some closed their businesses for one day at Rosh Hashanah, while others for the traditional two days. On the High Holidays, they would hold additional services to accommodate both groups. According to the local newspaper in 1934, “due to the fact there are both Reform and Orthodox here, [Rosh Hashanah] services will be held for both.” On the first day of Rosh Hashanah, they would hold an all-Hebrew service at 8 am, followed by an English service at 10 am. They would have an additional Hebrew service on the second day of Rosh Hashanah for Orthodox members. B’nai Israel would bring in visiting or students rabbis to lead High Holiday services. In 1930, Rabbi S. Tofilovsky led the services while in 1934 they brought rabbinic student Irving Klibansky from the Orthodox Hebrew Theological College in Chicago. Over time, B’nai Israel became more Reform, bringing in student rabbis from Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. In the late 1940s, Rabbi Morton Fierman of the Reform Temple Israel in Tulsa would visit Okmulgee periodically to lead services at B’nai Israel.

The Community Declines

In 1925, the Jewish Monitor and Jewish Weekly newspaper, published in Fort Worth, declared that “the Okmulgee Jewish community is bound to enlarge.” By 1927, 125 Jews lived in Okmulgee, though these numbers would soon decline with the rest of the town. By the end of the decade, the oil boom had gone bust, as Okmulgee began to shrink in population, dropping in half to only 17,000 people by 1930. Since then, the town has slowly declined, with only 13,000 people living in Okmulgee in 2000. This decline affected the Jewish community, which had dropped to 100 Jews by 1937. By 1946, B’nai Israel had about twenty families; its religious school had been discontinued and the group only met for the High Holidays. Nevertheless, they still brought in student rabbis from HUC to lead the holiday services. The decline continued, and by the mid-1950s, B’nai Israel became inactive. Not coincidentally, many of the long-term Jewish-owned stores in town closed in the 1950s as their owners died or retired and did not have children who wanted to continue the business. In 1963, only a few Jews remained in town, and there were no more Jewish-owned stores in Okmulgee. A few years later, the synagogue was sold and once again became a house.

The Community Declines

In 1925, the Jewish Monitor and Jewish Weekly newspaper, published in Fort Worth, declared that “the Okmulgee Jewish community is bound to enlarge.” By 1927, 125 Jews lived in Okmulgee, though these numbers would soon decline with the rest of the town. By the end of the decade, the oil boom had gone bust, as Okmulgee began to shrink in population, dropping in half to only 17,000 people by 1930. Since then, the town has slowly declined, with only 13,000 people living in Okmulgee in 2000. This decline affected the Jewish community, which had dropped to 100 Jews by 1937. By 1946, B’nai Israel had about twenty families; its religious school had been discontinued and the group only met for the High Holidays. Nevertheless, they still brought in student rabbis from HUC to lead the holiday services. The decline continued, and by the mid-1950s, B’nai Israel became inactive. Not coincidentally, many of the long-term Jewish-owned stores in town closed in the 1950s as their owners died or retired and did not have children who wanted to continue the business. In 1963, only a few Jews remained in town, and there were no more Jewish-owned stores in Okmulgee. A few years later, the synagogue was sold and once again became a house.

Ben Colchensky

Ben Colchensky

Although B’nai Israel was defunct by the 1960s, Jews continued to live in Okmulgee. Most notable was Ben Colchensky, who came to town in 1919 with his wife Minnie after spending a few years working for Sam Miller’s oilfield pipe and supply company in Tulsa. Colchensky started his own business called the Okmulgee Supply Company. Jacob Roberts later joined the business, and eventually took it over after Colchensky retired in 1958. Colchensky was very involved in civic life in Okmulgee. An active member of the Masons and the Rotary Club, he spent eight years as Director of Civil Defense for the city and served on the first board of the Okmulgee Memorial Hospital. After his retirement, Colchensky wrote a weekly column for the local newspaper called “Ben Sez” in which he shared his unique perspective on life and Okmulgee. In a 1973 article about him in the local paper, Colchensky declared, “if I had my life to live over again, I would join the same lodge, marry the same girl, and live in the same town.”

The Jewish Community in Okmulgee/Henryetta Today

Today, there are few vestiges of the small Jewish community that once lived in Okmulgee and Henryetta. B’nai Israel, which served the community for over 30 years, has been largely overlooked in many of the published sources on Oklahoma Jewish history. While the Jews of Okmulgee and Henryetta have passed away or moved on, they played a vital role in the development of their towns during the first half of the 20th century.