Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Tulsa, Oklahoma

Tulsa: Historical Overview

|

Though Tulsa was founded in 1882, it did not achieve prominence until oil was discovered in the area in 1901. This discovery transformed Tulsa from a sleepy town of 1,390 people in 1900 to a bustling city of 18,000 people a decade later. The boom times lasted for decades as the city’s population quadrupled in the 1910s, and reached 131,000 people by 1930. If oil gave birth to the city of Tulsa, it also profoundly shaped its small but significant Jewish community.

|

Stories of the Jewish Community in Tulsa

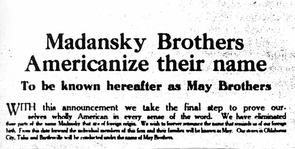

Ad run by the Madansky brothers announcing their name change

Ad run by the Madansky brothers announcing their name change

Jewish Businesses in Tulsa

For some Jews, Tulsa’s growth offered an economic opportunity. As early as 1902, Jews settled in Tulsa, often opening retail stores catering to the burgeoning population. Simon Jankowsky came to Tulsa from McAlester, Oklahoma, in 1904, opening a store called Palace Clothiers. The business thrived and Jankowsky built a grand new five-story building to house the store in 1912. Sig Werner came in 1905, and opened two general merchandise stores that remained in business for several decades. Max and Harry Madansky were drawn to Tulsa from Illinois in 1908. The Russian-born brothers rented a space on South Main Street and opened a men’s clothing store. When the Tulsa store was successful, their parents and other brothers moved to Oklahoma, where they opened branches of the store in Bartlesville, Muskogee, and Oklahoma City.

In 1921, the Madansky brothers changed the name of their stores and themselves, taking out a full-page ad in newspapers across the state to announce their decision. Now known as the May Brothers, they explained that the change was “the final step to prove ourselves wholly American in every sense of the word. We have eliminated those parts of the name Madansky that are of foreign origin. We wish to forever renounce the name that reminds us of our foreign birth.” At that time in America, nativists were calling for immigration restriction and questioning those who did not seem to be “100% American.” By changing their name and making such a public show of it, the Madansky brothers were seeking to avoid such charges and ensure that their business was not targeted by such groups as the Ku Klux Klan, which was rather prominent in Oklahoma in the 1920s. While the May Brothers store in Tulsa survived the Klan, it could not overcome the Great Depression. Max May built a new five-story building to house the expanding business just before the Depression hit. When business tailed off, the store was unable to pay its debts. Wracked with guilt over his poor business decision, Max May killed himself in 1931. His brother Harry continued to run the store until he closed it in 1934.

While the May Brothers chain was beset by tragedy, the one started by the Sanditen brothers was a huge success. Brothers Sam, Maurice, and Herman Sanditen opened a tire and auto supply store in Okmulgee, Oklahoma in 1918. They soon expanded the business, opening new locations of Oklahoma Tire & Supply across the state. In 1925, they moved the company headquarters to Tulsa. By 1943, there were 83 OTASCO stores in Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri, and Arkansas. The Sanditen brothers sold the business in 1960.

Sam Renberg, who came to the U.S. from Germany in 1889, moved to Tulsa from Enid, Oklahoma, in 1913 and opened a clothing store. Renberg’s Clothiers remained in business on Main Street for the next 80 years. Sam’s son George later took over the business, building it into a local institution while opening new locations in suburban shopping centers. The last Renberg store closed in 1999. Michael Froug, whose father Abraham had built the city's first brick two-story building in 1904, opened Froug's Department store with his cousin Ohren Smulian in 1929. Froug's eventually grew to become a chain of 17 stores before the family sold the business in 1980.

For some Jews, Tulsa’s growth offered an economic opportunity. As early as 1902, Jews settled in Tulsa, often opening retail stores catering to the burgeoning population. Simon Jankowsky came to Tulsa from McAlester, Oklahoma, in 1904, opening a store called Palace Clothiers. The business thrived and Jankowsky built a grand new five-story building to house the store in 1912. Sig Werner came in 1905, and opened two general merchandise stores that remained in business for several decades. Max and Harry Madansky were drawn to Tulsa from Illinois in 1908. The Russian-born brothers rented a space on South Main Street and opened a men’s clothing store. When the Tulsa store was successful, their parents and other brothers moved to Oklahoma, where they opened branches of the store in Bartlesville, Muskogee, and Oklahoma City.

In 1921, the Madansky brothers changed the name of their stores and themselves, taking out a full-page ad in newspapers across the state to announce their decision. Now known as the May Brothers, they explained that the change was “the final step to prove ourselves wholly American in every sense of the word. We have eliminated those parts of the name Madansky that are of foreign origin. We wish to forever renounce the name that reminds us of our foreign birth.” At that time in America, nativists were calling for immigration restriction and questioning those who did not seem to be “100% American.” By changing their name and making such a public show of it, the Madansky brothers were seeking to avoid such charges and ensure that their business was not targeted by such groups as the Ku Klux Klan, which was rather prominent in Oklahoma in the 1920s. While the May Brothers store in Tulsa survived the Klan, it could not overcome the Great Depression. Max May built a new five-story building to house the expanding business just before the Depression hit. When business tailed off, the store was unable to pay its debts. Wracked with guilt over his poor business decision, Max May killed himself in 1931. His brother Harry continued to run the store until he closed it in 1934.

While the May Brothers chain was beset by tragedy, the one started by the Sanditen brothers was a huge success. Brothers Sam, Maurice, and Herman Sanditen opened a tire and auto supply store in Okmulgee, Oklahoma in 1918. They soon expanded the business, opening new locations of Oklahoma Tire & Supply across the state. In 1925, they moved the company headquarters to Tulsa. By 1943, there were 83 OTASCO stores in Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri, and Arkansas. The Sanditen brothers sold the business in 1960.

Sam Renberg, who came to the U.S. from Germany in 1889, moved to Tulsa from Enid, Oklahoma, in 1913 and opened a clothing store. Renberg’s Clothiers remained in business on Main Street for the next 80 years. Sam’s son George later took over the business, building it into a local institution while opening new locations in suburban shopping centers. The last Renberg store closed in 1999. Michael Froug, whose father Abraham had built the city's first brick two-story building in 1904, opened Froug's Department store with his cousin Ohren Smulian in 1929. Froug's eventually grew to become a chain of 17 stores before the family sold the business in 1980.

Sylvan Goldman

Sylvan Goldman

Several of the Jews who settled in Tulsa during the early 20th century entered the grocery business. Nathan Gens moved to Tulsa in 1917 and opened a small grocery store. His brother-in-law, Herman Barall, soon joined him in the business, and the two began to open additional grocery stores called the Gens Cash Stores. The chain grew to 56 stores before they sold it to a large company in 1928. In 1918, the Jewish grocers of Tulsa established the Buyers Cooperative of Jewish Grocers to keep their wholesale costs down. At first only Jews were able to join, but it began allowing non-Jewish grocers in 1928. Changing its name to Associated Grocers, it soon became the largest association of independent grocers in the state. Sylvan Goldman moved to Tulsa from Ardmore in 1920 and opened the city’s first supermarket grocery store. Working with his brother Alfred, they opened 21 Sun Grocery Markets across Oklahoma by 1921. They sold the chain to Safeway in 1929, but later bought the Humpty-Dumpty grocery chain. Goldman achieved fame and lasting wealth when he invented the shopping cart in 1936. He started the Folding Basket Carrier Company to manufacture and sell them, and later developed the personal airport luggage cart. Goldman was inducted into the Oklahoma Hall of Fame in 1971.

Mansion built by David Travis now houses

Mansion built by David Travis now houses the Tulsa Historical Society Museum.

A number of Tulsa Jews, many of them recent immigrants, found tremendous wealth in the oil business. Lionel Aaronson was born in Poland and lived in New York before moving to Tulsa. In 1908, he started the Pure Oil Company with Russian immigrant Sam Rabinowitz, whose brother David also joined the business. The Rabinowitz brothers changed their last name to Travis and later built twin Italian revival mansions on adjoining lots in Tulsa. Each house had a large swimming pool, tennis court, as well as a mikvah (ritual bath) so the families could observe the traditional Jewish practices of purification. The brothers did not live in the grand mansions for very long as they had to sell them after oil prices collapsed in the early 1920s. David’s home later became the Tulsa Garden Center, while Sam’s house became the museum of the Tulsa Historical Society. Both Sam and David Travis later moved to Israel, where they are buried on Mount Scopus. Lionel Aaronson’s son, Alfred, later took over the oil company, and became one of the city’s most prominent businessmen. In 1965, he led the way in constructing a new public library for the city, which named its auditorium after Aaronson.

Several Tulsa Jews entered the oil business through the traditional Jewish field of scrap metal. In Tulsa, scrap metal often meant buying up used pipe and metal from oil rigs. Lithuanian-born Sam Miller came to Tulsa in 1916 and started an oil field scrap metal business. By 1930, he had become a “wildcatter,” prospecting for oil in the area around Tulsa. After striking oil, Miller became a major philanthropist, supporting Jewish institutions across the country. Isadore Nadel came to Tulsa initially as a kosher butcher. Later, he opened a small grocery store. He later got into the oil business and became one of the wealthiest Jews in the state. Joe Davis and N.C. Livingston also became successful oilmen.

Several Tulsa Jews entered the oil business through the traditional Jewish field of scrap metal. In Tulsa, scrap metal often meant buying up used pipe and metal from oil rigs. Lithuanian-born Sam Miller came to Tulsa in 1916 and started an oil field scrap metal business. By 1930, he had become a “wildcatter,” prospecting for oil in the area around Tulsa. After striking oil, Miller became a major philanthropist, supporting Jewish institutions across the country. Isadore Nadel came to Tulsa initially as a kosher butcher. Later, he opened a small grocery store. He later got into the oil business and became one of the wealthiest Jews in the state. Joe Davis and N.C. Livingston also became successful oilmen.

Rev. Max Himmelstein

Rev. Max Himmelstein

Organized Jewish Life in Tulsa

Like the Travis brothers, many Jewish oilmen were religiously observant. Indeed, most of the earliest Jewish settlers in Tulsa, many of whom were from Varklan, Latvia, were Orthodox; they organized a minyan by 1903. A rabbi from South Africa, I. Kuperstein, led the small group in its early years. In 1905, the group, numbering 12 families, brought in a Mr. Racow to lead services and slaughter kosher meat. Rev. Max Himmelstein served this role starting in 1908. After meeting in private homes, the group started holding services in a special room on the second floor of the Producers Supply Building, which was owned by N.C. Livingston, the unofficial leader of the group. After Rabbi Kuperstein left in 1911, Rev. Himmelstein became the spiritual leader, holding the daily minyans in his home. In 1912, the group bought land for a cemetery and established a chevra kadisha to ensure that Jews were buried according to Orthodox practice. By 1914, there were around 75 Orthodox families in Tulsa, who had two different kosher meat markets to choose from.

In 1915, the group was officially chartered as Congregation B’nai Emunah, with Marion Travis as its first president. The congregation bought land on S. Cheyenne Street and built a small synagogue that could seat 250 people, which also included a mikvah and a separate seating gallery for women. The congregation was Orthodox, with its founding constitution declaring that all prayers must be read in Hebrew and that “members who shall act contrary to [Orthodox practices] or try to introduce reform measures shall…be suspended or expelled.” Yet the fact that the constitution was written in English, not Yiddish, was an indication that the members of B’nai Emunah had already began the process of assimilation, which would eventually lead the congregation away from strict Orthodoxy.

Although it was an Orthodox congregation, B’nai Emunah hired Rabbi Morris Teller, a graduate of the Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary, in 1916. There were often disputes within the young congregation. When Rabbi Teller introduced a Friday night service in 1922, the traditionalists balked and prevented Rev. Himmelstein from chanting at the service. That same year, a dispute over shochets led a more traditional faction, led by Sam and David Travis, to leave B’nai Emunah and form a new congregation, Ohel Jacob. The group soon rejoined B’nai Emunah, and David Travis even became president of the unified congregation in 1925. Lionel Aaronson remained a member of B’nai Emunah, but built a chapel in his house and held regular services there. Claiming that his house was too far from the synagogue to walk on the Sabbath, Aaronson’s minyan even hired its own cantor and shochet,

Like the Travis brothers, many Jewish oilmen were religiously observant. Indeed, most of the earliest Jewish settlers in Tulsa, many of whom were from Varklan, Latvia, were Orthodox; they organized a minyan by 1903. A rabbi from South Africa, I. Kuperstein, led the small group in its early years. In 1905, the group, numbering 12 families, brought in a Mr. Racow to lead services and slaughter kosher meat. Rev. Max Himmelstein served this role starting in 1908. After meeting in private homes, the group started holding services in a special room on the second floor of the Producers Supply Building, which was owned by N.C. Livingston, the unofficial leader of the group. After Rabbi Kuperstein left in 1911, Rev. Himmelstein became the spiritual leader, holding the daily minyans in his home. In 1912, the group bought land for a cemetery and established a chevra kadisha to ensure that Jews were buried according to Orthodox practice. By 1914, there were around 75 Orthodox families in Tulsa, who had two different kosher meat markets to choose from.

In 1915, the group was officially chartered as Congregation B’nai Emunah, with Marion Travis as its first president. The congregation bought land on S. Cheyenne Street and built a small synagogue that could seat 250 people, which also included a mikvah and a separate seating gallery for women. The congregation was Orthodox, with its founding constitution declaring that all prayers must be read in Hebrew and that “members who shall act contrary to [Orthodox practices] or try to introduce reform measures shall…be suspended or expelled.” Yet the fact that the constitution was written in English, not Yiddish, was an indication that the members of B’nai Emunah had already began the process of assimilation, which would eventually lead the congregation away from strict Orthodoxy.

Although it was an Orthodox congregation, B’nai Emunah hired Rabbi Morris Teller, a graduate of the Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary, in 1916. There were often disputes within the young congregation. When Rabbi Teller introduced a Friday night service in 1922, the traditionalists balked and prevented Rev. Himmelstein from chanting at the service. That same year, a dispute over shochets led a more traditional faction, led by Sam and David Travis, to leave B’nai Emunah and form a new congregation, Ohel Jacob. The group soon rejoined B’nai Emunah, and David Travis even became president of the unified congregation in 1925. Lionel Aaronson remained a member of B’nai Emunah, but built a chapel in his house and held regular services there. Claiming that his house was too far from the synagogue to walk on the Sabbath, Aaronson’s minyan even hired its own cantor and shochet,

B'nai Emunah's first synagogue

B'nai Emunah's first synagogue

These splits were facilitated by the oil wealth of B’nai Emunah’s members, who could afford to fund these breakaway groups. Each of B’nai Emunah’s ten officers and board members in 1916 were in the oil business. Eight were oil producers, while two were in the oil field supply business. Most of them were young; their average age was 33 years. Eight of the ten were immigrants from the Russian empire, though most had been in the U.S. for several years. Oil was so central to the members of B’nai Emunah that they sometimes held special all-night minyans when one of them was drilling for oil, reciting Thilim (Psalms) prayers for their success. The relative wealth of B’nai Emunah stands in stark contrast to most other small Orthodox congregations founded around the same time in the U.S., most of which were initially made up of poor immigrants. Clearly, the oil business had a significant impact on Tulsa’s Orthodox congregation.

Tulsa is also unusual in that Orthodox Jews organized before Reform Jews did. In 1914, Rabbi Joseph Blatt of Oklahoma City’s Temple B’nai Israel traveled to Tulsa to try to get the city’s Reform Jews to form a congregation. Finally, in December, 1914, they established Temple Israel. Interestingly, the leadership of the fledgling Reform congregation was far more typical of Southern Jewish occupational patterns than those of B’nai Emunah. Only one of the 11 board members in 1919 were in the oil business; eight were merchants. Almost half of them, 45%, were native born, while those who were immigrants tended to come from Germany or France and had been in the United States for several decades. Initially, Temple Israel was smaller and poorer than B’nai Emunah

Tulsa is also unusual in that Orthodox Jews organized before Reform Jews did. In 1914, Rabbi Joseph Blatt of Oklahoma City’s Temple B’nai Israel traveled to Tulsa to try to get the city’s Reform Jews to form a congregation. Finally, in December, 1914, they established Temple Israel. Interestingly, the leadership of the fledgling Reform congregation was far more typical of Southern Jewish occupational patterns than those of B’nai Emunah. Only one of the 11 board members in 1919 were in the oil business; eight were merchants. Almost half of them, 45%, were native born, while those who were immigrants tended to come from Germany or France and had been in the United States for several decades. Initially, Temple Israel was smaller and poorer than B’nai Emunah

Temple Israel's first synagogue

Temple Israel's first synagogue

While Temple Israel was founded at the end of 1914, it did not hold its first services until Rosh Hashanah in 1915. A.J. Feldman, a student rabbi from Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati, led High Holiday services the first two years, which were held at the Elk’s Club and the Ohio Building. By 1916, Temple Israel had started a religious school and was holding regular Shabbat services. The following year, they purchased a plot of land with two small cottages on it. The Ladies Aid Society, which later became the Sisterhood, donated a Torah to the congregation and led the religious school in one of the cottages. In 1917, they received a formal charter and joined the Reform Union of American Hebrew Congregations. Rabbi Blatt of Oklahoma City and Rabbi George Fox of Fort Worth would regularly visit the Tulsa congregation in its early years. By 1917, Temple Israel had hired its own rabbi, J.B. Menkes. Soon, the congregation tore down the cottages and began to construct its first temple. They met in the local courthouse while the synagogue was being built. Finally, in 1919, Temple Israel dedicated its new $75,000 home in a public ceremony featuring Rabbi Blatt and several local Christian ministers. Temple Israel had 54 members at the time of the dedication, which was about half the size of B’nai Emunah at the time.

Rabbi Abraham Schusterman

Rabbi Abraham Schusterman

In 1935, Rabbi Abraham Schusterman became Temple Israel’s spiritual leader, and introduced elements of traditional Judaism to the worship service, including the bar mitzvah ritual. He also wore a robe and tallis on the bimah during services, while his predecessors had worn suits. Rabbi Schusterman also added Hebrew instruction to the religious school curriculum. These movements away from Classical Reform Judaism were not that difficult since the congregation always had more traditional members. When the Sisterhood bought an organ for the first temple, there was serious opposition to it since it violated traditional practices; the congregation approved it by only three votes. In the early 1920s, some members of Temple Israel wanted to hire B’nai Emunah’s Rabbi Teller as their spiritual leader and even proposed a merger of the two congregations, expressing a willingness to wear yarmulkes and use the Orthodox prayer book. Although he led Temple Israel away from Classical Reform, Rabbi Schusterman was a strong believer in the social justice principles of Reform Judaism. During his tenure, Temple Israel became the first white house of worship in Tulsa to invite a black clergyman to speak from the pulpit. By 1935, Temple Israel had 200 families.

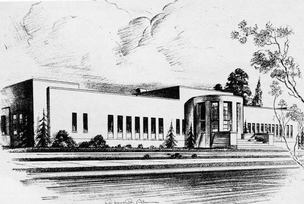

Temple Israel's second synagogue, built in 1932

Temple Israel's second synagogue, built in 1932

B’nai Emunah also thrived as Tulsa’s Jewish population continued to grow during the years before World War II, reaching 2,850 people in 1937. When Rabbi Teller left B’nai Emunah in 1925, the congregation went almost two years without a full-time rabbi. Since they also employed a chazzan/shochet (cantor/kosher butcher), who usually led prayer services and read Torah, they could get along without a rabbi. Rev. M.Z Tofield filled this supporting role from 1927 until 1952. Rabbi Harry Epstein replaced Teller in 1927, only staying a year, before leaving for Atlanta, where he would go on to have a long and illustrious career. In 1930, the congregation hired another future rabbinic star, Oscar Fasman. A 22 year-old graduate of the Orthodox Hebrew Theological College in Chicago, Fasman led B’nai Emunah for the next decade. During his tenure, B’nai Emunah formally affiliated with the Orthodox Union. After leaving for a pulpit in Ottawa, Rabbi Fasman was named president of the Chicago seminary, becoming an important leader in modern Orthodox Judaism in America

Rabbi Fasman and graduating religious school students, 1936

Rabbi Fasman and graduating religious school students, 1936

Members of B’nai Emunah built a Jewish Institute, designed to be a community center, in 1922. Reflecting the scattered nature of the Orthodox synagogue’s membership, the Jewish Institute was 1.5 miles away from B’nai Emunah. Nevertheless, the Orthodox synagogue’s Talmud Torah school started meeting at the Institute, a vast improvement over the shul’s basement, where they had been meeting. The B’nai Emunah Sisterhood, which had been founded in 1921, held their meetings and functions at the Institute. The heyday of the Jewish Institute was short-lived, as financial troubles forced it to close in 1930. The building was still used by Jewish groups occasionally. Later in the 1930s, member of B’nai Emunah who lived on the northside met there for High Holiday services since they lived too far from the synagogue to walk there. Abe Borofsky and Harold Smith were the lay leaders for the northside group.

By the mid-1930s, B’nai Emunah had outgrown its building and members began to raise money for a new one. It took them a few years due to the effects of the Depression, but they finally broke ground in 1941. When they dedicated the new synagogue on South Owasso Street in 1942, Tulsa Mayor C.H. Veale took part in the ceremony. With their new building, B’nai Emunah had to handle a dispute over the seating. Some of the women of the congregation refused to sit in a separate balcony, and called for mixed gender seating. The leaders of B’nai Emunah worked out a compromise in which men and women could sit together on one side of the sanctuary, while only men would sit on the other side; a high curtail down the center aisle separated the two sections. This unusual seating arrangement reflected the hybrid nature of the congregation, which was a mix of Orthodox and Conservative Judaism. In 1944, B’nai Emunah hired a graduate of the Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary, Norman Shapiro, to be its rabbi. Yet when Rabbi Shapiro left in 1949, they replaced him with Arthur Kahn, who was ordained by the Orthodox Yeshiva University.

Just 15 miles southwest of Tulsa, Jewish merchants in the small town of Sapulpa organized a congregation of their own around 1916. The congregation, which held daily Orthodox services initially, had about 25 families when it was founded. Traveling to Tulsa for a daily minyan or Shabbat services was not feasible for these Orthodox Jews, so they held their own. Four families from nearby Bristow also joined the congregation, which met in a specially furnished room in the home of the Minsky family. By 1946, the group was still meeting, but only for High Holidays as there were only ten Jewish families left in Sapulpa and Bristow. Those remaining traveled to nearby Tulsa for regular services.

By the mid-1930s, B’nai Emunah had outgrown its building and members began to raise money for a new one. It took them a few years due to the effects of the Depression, but they finally broke ground in 1941. When they dedicated the new synagogue on South Owasso Street in 1942, Tulsa Mayor C.H. Veale took part in the ceremony. With their new building, B’nai Emunah had to handle a dispute over the seating. Some of the women of the congregation refused to sit in a separate balcony, and called for mixed gender seating. The leaders of B’nai Emunah worked out a compromise in which men and women could sit together on one side of the sanctuary, while only men would sit on the other side; a high curtail down the center aisle separated the two sections. This unusual seating arrangement reflected the hybrid nature of the congregation, which was a mix of Orthodox and Conservative Judaism. In 1944, B’nai Emunah hired a graduate of the Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary, Norman Shapiro, to be its rabbi. Yet when Rabbi Shapiro left in 1949, they replaced him with Arthur Kahn, who was ordained by the Orthodox Yeshiva University.

Just 15 miles southwest of Tulsa, Jewish merchants in the small town of Sapulpa organized a congregation of their own around 1916. The congregation, which held daily Orthodox services initially, had about 25 families when it was founded. Traveling to Tulsa for a daily minyan or Shabbat services was not feasible for these Orthodox Jews, so they held their own. Four families from nearby Bristow also joined the congregation, which met in a specially furnished room in the home of the Minsky family. By 1946, the group was still meeting, but only for High Holidays as there were only ten Jewish families left in Sapulpa and Bristow. Those remaining traveled to nearby Tulsa for regular services.

B'nai Emunah's new synagogue, built in 1942

B'nai Emunah's new synagogue, built in 1942

Jewish Organizations in Tulsa

While Jewish life in Tulsa centered around the two congregations, Tulsa Jews established several other organizations, many of which worked to help those in need. Nona Solomon established the Ladies Aid Society, which raised money to help Jewish transients who came through Tulsa. In 1920, Solomon became the first executive secretary of the Federation of Jewish Charities, which helped local Jews in need. Later the Federation of Jewish Charities became the family service arm of the Tulsa Community Fund, which was established in 1924. Solomon ran the Federation of Jewish Charities until her death in 1944. Solomon was also active in the Tulsa chapter of the Council of Jewish Women, founded in 1917. The CJW started the monthly Tulsa Jewish Review newspaper in 1929, which Solomon edited for 15 years. In 1917, Eastern European Jewish immigrants founded the Mutual Aid Bank, which offered low interest business loans to its members. Proceeds from the bank helped to fund the Jewish Institute. When the Mutual Aid Bank failed in in the crash of 1929, Jews founded a Hebrew Free Loan Society to take its place. Although the free loan society survived for many years, few Tulsa Jews needed to use it. In 1945, less than $1000 was loaned out. In 1928, a group of Tulsa Jews founded the Varklan Relief Society, which worked to raise money to support their friends and family who remained in the area of Latvia where many of Tulsa’s Jews had come from.

While Jewish life in Tulsa centered around the two congregations, Tulsa Jews established several other organizations, many of which worked to help those in need. Nona Solomon established the Ladies Aid Society, which raised money to help Jewish transients who came through Tulsa. In 1920, Solomon became the first executive secretary of the Federation of Jewish Charities, which helped local Jews in need. Later the Federation of Jewish Charities became the family service arm of the Tulsa Community Fund, which was established in 1924. Solomon ran the Federation of Jewish Charities until her death in 1944. Solomon was also active in the Tulsa chapter of the Council of Jewish Women, founded in 1917. The CJW started the monthly Tulsa Jewish Review newspaper in 1929, which Solomon edited for 15 years. In 1917, Eastern European Jewish immigrants founded the Mutual Aid Bank, which offered low interest business loans to its members. Proceeds from the bank helped to fund the Jewish Institute. When the Mutual Aid Bank failed in in the crash of 1929, Jews founded a Hebrew Free Loan Society to take its place. Although the free loan society survived for many years, few Tulsa Jews needed to use it. In 1945, less than $1000 was loaned out. In 1928, a group of Tulsa Jews founded the Varklan Relief Society, which worked to raise money to support their friends and family who remained in the area of Latvia where many of Tulsa’s Jews had come from.

Varklan Relief Society

Varklan Relief Society

Despite Tulsa Jews’ concern for the plight of their coreligionists in Europe, they were relatively late in establishing Zionist organizations. A Hadassah chapter formed in 1918, but soon disbanded. A Junior Hadassah, created in 1921, was more successful. In 1924, Tulsa Jews founded a local chapter of the Zionist Organization of America. Led by Gershon Fenster, the group quickly grew from 40 founding members to 150 by 1925. Despite this promising start, the group disbanded by 1930. Fenster restarted the group in 1932, and finally found success. The ZOA chapter held a weekly lunch in the late 1930s that included a discussion of contemporary Jewish issues. By 1946, the group had 262 members. Hadassah was reorganized in 1935, and within a decade it was the largest Jewish women’s organization in the city. In 1926, Libby Singer created a chapter of Pioneer Women, a socialist Zionist organization, though it was never as large as Hadassah, to which Singer also belonged. These groups mainly worked to raise money for the Jewish settlement in Palestine, though they also sponsored many social and cultural events. Despite the fact that organized Zionism was late to arrive in Tulsa, some prominent community leaders were strong supporters of the movement. In 1919, Alfred Aaronson traveled to Palestine and wrote on his passport application that the purpose of the trip was “the Zionist movement.” There was little anti-Zionism in Tulsa; the American Council for Judaism, which opposed a Jewish state, never had a local chapter or much support in Tulsa.

Gershon Fenster, founder of

Tulsa's Zionist organization

Gershon Fenster, founder of

Tulsa's Zionist organization

In 1917, a group of Tulsa Jews, led by Louis Krasner, W.J. Levine, and Abe Abend, founded a chapter of the Jewish National Workers Alliance, a socialist, secular fraternal society. The Tulsa chapter was more social than political; though the group was anti-religious, it sponsored a Yom Kippur dance at least once. The chapter still existed in 1946, though it was never very large.

In 1938, the Tulsa Jewish Community Council was founded to coordinate all of the different Jewish organizations in the city and to centralize fundraising in the community. Gershon Fenster was its first president. Emil Solomon, Nona Solomon’s husband, served as the council’s executive director from 1939 to 1959. The council, later renamed the Tulsa Jewish Federation, ran an annual fundraising campaign that supported Jewish causes at home and abroad. With its great wealth, the Tulsa Jewish community became one of highest per capita givers in Federation fundraising campaigns in the country. Members of both congregations were active in the council, which served to bind the Tulsa Jewish community together. The council also worked to promote tolerance and combat anti-Semitism through the work of the Public Relations Committee, led by Samuel Boorstin in its early years.

In 1938, the Tulsa Jewish Community Council was founded to coordinate all of the different Jewish organizations in the city and to centralize fundraising in the community. Gershon Fenster was its first president. Emil Solomon, Nona Solomon’s husband, served as the council’s executive director from 1939 to 1959. The council, later renamed the Tulsa Jewish Federation, ran an annual fundraising campaign that supported Jewish causes at home and abroad. With its great wealth, the Tulsa Jewish community became one of highest per capita givers in Federation fundraising campaigns in the country. Members of both congregations were active in the council, which served to bind the Tulsa Jewish community together. The council also worked to promote tolerance and combat anti-Semitism through the work of the Public Relations Committee, led by Samuel Boorstin in its early years.

Emil Solomon

Emil Solomon

Anti-Semitism in Tulsa

Tulsa Jews were concerned about anti-Semitism, which was relatively prevalent in the city in the 1930s and 1940s. According to Rabbi Randall Falk, who led Temple Israel in 1944, Jews faced informal hiring restrictions in the local school system and among large oil companies. Despite their active involvement in the oil industry, only one Jew, Leo Meyer, had an executive position at a non-Jewish owned oil company in Tulsa. Jews were also excluded from local bank boards and from the leadership of the local Chamber of Commerce. In 1944, the Jewish Community Council formed a special committee tasked with improving relations between Jewish businessmen and the Chamber of Commerce. Jews were also excluded from local country clubs, while only a few were allowed to join the elite Tulsa City Club. Writing in 1946, Falk argued that “the Jew has not received proportional recognition in any field of Tulsa business or industry.

Local Jews fought against more virulent strands of anti-Semitism. When the Silver Shirts, a pro-Nazi, anti-Semitic organization tried to open a headquarters in Tulsa in 1934, David Travis led a committee of local Jews who rallied prominent civic leaders to prevent it. When someone painted a large swastika on Temple Israel in 1939, the local newspapers and many Christian churches offered their sympathy and support.

Tulsa Jews were also sensitive to anti-Semitism in Europe, and worked to call attention to Nazi atrocities during World War II. In 1943, the Community Council organized a day of fasting and prayer in response to reports of Hitler’s killing of Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe. The Tulsa Ministerial Alliance issued a resolution condemning the killings, while many Christian ministers spoke to their congregations about the issue. That same year, the council organized a mass meeting at B’nai Emunah to protest the murder of European Jews. Oklahoma Governor Robert Kerr spoke at the event.

Tulsa Jews were concerned about anti-Semitism, which was relatively prevalent in the city in the 1930s and 1940s. According to Rabbi Randall Falk, who led Temple Israel in 1944, Jews faced informal hiring restrictions in the local school system and among large oil companies. Despite their active involvement in the oil industry, only one Jew, Leo Meyer, had an executive position at a non-Jewish owned oil company in Tulsa. Jews were also excluded from local bank boards and from the leadership of the local Chamber of Commerce. In 1944, the Jewish Community Council formed a special committee tasked with improving relations between Jewish businessmen and the Chamber of Commerce. Jews were also excluded from local country clubs, while only a few were allowed to join the elite Tulsa City Club. Writing in 1946, Falk argued that “the Jew has not received proportional recognition in any field of Tulsa business or industry.

Local Jews fought against more virulent strands of anti-Semitism. When the Silver Shirts, a pro-Nazi, anti-Semitic organization tried to open a headquarters in Tulsa in 1934, David Travis led a committee of local Jews who rallied prominent civic leaders to prevent it. When someone painted a large swastika on Temple Israel in 1939, the local newspapers and many Christian churches offered their sympathy and support.

Tulsa Jews were also sensitive to anti-Semitism in Europe, and worked to call attention to Nazi atrocities during World War II. In 1943, the Community Council organized a day of fasting and prayer in response to reports of Hitler’s killing of Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe. The Tulsa Ministerial Alliance issued a resolution condemning the killings, while many Christian ministers spoke to their congregations about the issue. That same year, the council organized a mass meeting at B’nai Emunah to protest the murder of European Jews. Oklahoma Governor Robert Kerr spoke at the event.

Isadore Nadel, president of B'nai Emunah

Isadore Nadel, president of B'nai Emunah and chef of Seder dinner for

1500 Jewish soldiers in 1943.

World War II and the Post-War Era

During World War II, Tulsa Jews hosted Jewish servicemen stationed in Oklahoma. In 1943, members of B’nai Emunah served a kosher seder dinner for 1500 people at Camp Gruber. Congregation president Isadore Nadel was the lead chef for the meal, which was cooked at B’nai Emunah and then driven to the Muskogee base under military police escort. Both Tulsa congregations held social events for the soldiers during the war. The Jewish Community Council also organized activities and religious services for the soldiers.

After the war, both Tulsa congregations expanded. B’nai Emunah, which had almost 300 members in 1950, added a new education wing to their synagogue to handle the growing number of children in the congregation. By 1957, they had almost 250 children in their religious school. In 1959, they completely redid the building, adding a new sanctuary, auditorium, and two kosher kitchens. The $750,000 project resulted in a new larger synagogue on land adjacent to the old one. By 1966, B’nai Emunah had about 450 members.

Temple Israel also flourished in the decades after World War II, growing from 215 families in 1945 to 385 in 1962. With this growth, Temple Israel decided to build a new synagogue, buying land in 1950. Since they could no longer fit in their old temple, the congregation met for High Holiday services at the Tulsa University Student Union in the early 1950s. Finally, in 1955, Temple Israel built a new synagogue on East 22nd Place. When the building flooded in 1984, they had to remodel, adding the Moe Gimp Early Learning Center, which houses a thriving preschool program. In 1985, Temple Israel reached a peak of 558 member families.

During World War II, Tulsa Jews hosted Jewish servicemen stationed in Oklahoma. In 1943, members of B’nai Emunah served a kosher seder dinner for 1500 people at Camp Gruber. Congregation president Isadore Nadel was the lead chef for the meal, which was cooked at B’nai Emunah and then driven to the Muskogee base under military police escort. Both Tulsa congregations held social events for the soldiers during the war. The Jewish Community Council also organized activities and religious services for the soldiers.

After the war, both Tulsa congregations expanded. B’nai Emunah, which had almost 300 members in 1950, added a new education wing to their synagogue to handle the growing number of children in the congregation. By 1957, they had almost 250 children in their religious school. In 1959, they completely redid the building, adding a new sanctuary, auditorium, and two kosher kitchens. The $750,000 project resulted in a new larger synagogue on land adjacent to the old one. By 1966, B’nai Emunah had about 450 members.

Temple Israel also flourished in the decades after World War II, growing from 215 families in 1945 to 385 in 1962. With this growth, Temple Israel decided to build a new synagogue, buying land in 1950. Since they could no longer fit in their old temple, the congregation met for High Holiday services at the Tulsa University Student Union in the early 1950s. Finally, in 1955, Temple Israel built a new synagogue on East 22nd Place. When the building flooded in 1984, they had to remodel, adding the Moe Gimp Early Learning Center, which houses a thriving preschool program. In 1985, Temple Israel reached a peak of 558 member families.

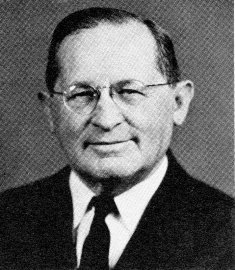

Rabbi Arthur Kahn

Rabbi Arthur Kahn

The Late 20th Century

Over the last several decades of the 20th century, B’nai Emunah enjoyed stability in its spiritual leaders. Rabbi Arthur Kahn led B’nai Emunah from 1949 to 1985, managing the congregation’s transition from Orthodoxy to Conservative Judaism. He introduced the bat mitzvah ceremony in 1956. By the late 1960s, B’nai Emunah had joined the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism; later, they instituted mixed gender seating throughout the sanctuary. Rabbi Kahn’s successor, Rabbi Marc Fitzerman, who has led B’nai Emunah since 1985, continued this transition, slowly instituting gender equality within the congregation and the worship service. Rev. Isaac Paru, who came in 1952, spent over 35 years as Torah reader, chazzan, and shochet for the congregation.

Temple Israel also enjoyed rabbinic stability for the first time in its history. When Rabbi Morton Fierman left Tulsa in 1951, after staying only four years, Rabbi Norbert Rosenthal took over the congregation. Rabbi Rosenthal led Temple Israel until he retired in 1976. Rabbi Charles Sherman replaced him, serving until his retirement in 2013. Harry Sebran, who came in 1964, spent over 25 years as Temple Israel’s cantor.

Over the last several decades of the 20th century, B’nai Emunah enjoyed stability in its spiritual leaders. Rabbi Arthur Kahn led B’nai Emunah from 1949 to 1985, managing the congregation’s transition from Orthodoxy to Conservative Judaism. He introduced the bat mitzvah ceremony in 1956. By the late 1960s, B’nai Emunah had joined the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism; later, they instituted mixed gender seating throughout the sanctuary. Rabbi Kahn’s successor, Rabbi Marc Fitzerman, who has led B’nai Emunah since 1985, continued this transition, slowly instituting gender equality within the congregation and the worship service. Rev. Isaac Paru, who came in 1952, spent over 35 years as Torah reader, chazzan, and shochet for the congregation.

Temple Israel also enjoyed rabbinic stability for the first time in its history. When Rabbi Morton Fierman left Tulsa in 1951, after staying only four years, Rabbi Norbert Rosenthal took over the congregation. Rabbi Rosenthal led Temple Israel until he retired in 1976. Rabbi Charles Sherman replaced him, serving until his retirement in 2013. Harry Sebran, who came in 1964, spent over 25 years as Temple Israel’s cantor.

|

Multimedia: Tulsa native Malcolm Milsten and his wife Paula have both served as president of Temple Israel. In this video clip from July 2012, they recall the 1984 flood that caused significant damage to the Reform synagogue.

|

Jack Zarrow

Jack Zarrow

Jewish Philanthropy in Tulsa

After World War II, a handful of Tulsa Jews continued to amass great fortunes in the oil industry, becoming some of the city’s leading philanthropists. Henry Zarrow started out in the junk business as a boy, convincing his father Sam to sell his grocery store and join him in his scrap metal operation. Their business, Sooner Scrap & Iron, began to focus on selling both new and used pipe for oil fields. With brothers Henry and Jack Zarrow at the helm, the renamed Sooner Pipe & Supply sold pipe to the largest oil companies in the world, becoming tremendously successful. The Zarrows sold the business in 1998, and focused their attention on their significant philanthropic work. The Maxine and Jack Zarrow Family Foundation supported most of Tulsa’s Jewish institutions while also giving generously to many civic and charitable causes in the city. The Henry and Ann Zarrow Foundation established a college scholarship program for Tulsa students, while also funding a day center for the homeless and the local food bank.

After World War II, a handful of Tulsa Jews continued to amass great fortunes in the oil industry, becoming some of the city’s leading philanthropists. Henry Zarrow started out in the junk business as a boy, convincing his father Sam to sell his grocery store and join him in his scrap metal operation. Their business, Sooner Scrap & Iron, began to focus on selling both new and used pipe for oil fields. With brothers Henry and Jack Zarrow at the helm, the renamed Sooner Pipe & Supply sold pipe to the largest oil companies in the world, becoming tremendously successful. The Zarrows sold the business in 1998, and focused their attention on their significant philanthropic work. The Maxine and Jack Zarrow Family Foundation supported most of Tulsa’s Jewish institutions while also giving generously to many civic and charitable causes in the city. The Henry and Ann Zarrow Foundation established a college scholarship program for Tulsa students, while also funding a day center for the homeless and the local food bank.

Lynn Schusterman

Lynn Schusterman

Charles Schusterman also started in the scrap metal business, joining his father Sam’s company. Later, Charles started the Samson Investment Company in 1971, which was in the natural gas exploration and production business. In the early 1970s, Schusterman bought Amerada Hess’ oil fields in California, just before the price of oil skyrocketed. With their newfound wealth, Charles and his wife Lynn created a charitable foundation in 1987 that has had a profound impact on the Jewish world. The Charles and Lynn Schusterman Foundation gives 75% of its donations to Jewish causes, many in Israel, while also supporting local charities. They donated $10 million to create the Schusterman Center at Oklahoma University-Tulsa, which brought a major medical teaching school to the city. They are also major funders of Birthright Israel and have supported Jewish Studies programs at the Universities of Texas and Oklahoma. After Charles died in 2000, Lynn carried on the philanthropic work while her daughter Stacy Schusterman took over Samson Resources Company.

George Kaiser

George Kaiser

In 1969, George Kaiser took over the Kaiser-Francis Oil Company, which had been started by his father and uncle after they escaped from Nazi Germany before the war. Kaiser expanded into banking in 1990 when he bought the Bank of Oklahoma from the FDIC, becoming one of the wealthiest people in the United States. According to a 2008 study in Businessweek Magazine, Kaiser was the third largest philanthropist in the country, behind Bill & Melinda Gates and Warren Buffett. His George Kaiser Family Foundation is focused on fighting childhood poverty and supporting early childhood education. In 1998, he established the Tulsa Community Foundation to help coordinate charitable fundraising in the city.

This tremendous wealth has had a big impact on the Tulsa Jewish community, which has an institutional footprint far beyond the relatively small size of the population, which has never numbered more than 3000 people. Irving Frank and others donated land on 71st Street to become a Jewish campus. Now called the Zarrow Campus, it houses the Tulsa Jewish Federation offices, the Charles Schusterman Jewish Community Center, the Mizel Jewish Community Day School, the Sherwin Miller Jewish Museum, and the Tulsa Jewish Retirement and Health Center. In recent years, both congregations have remodeled their synagogues. In 2000, B’nai Emunah tore down its building, except for the sanctuary, and built a brand new synagogue around it. During the two years it took to complete the project, B’nai Emunah met at All Soul’s Unitarian Church. Temple Israel remodeled its 50 year-old building in 2005.

This tremendous wealth has had a big impact on the Tulsa Jewish community, which has an institutional footprint far beyond the relatively small size of the population, which has never numbered more than 3000 people. Irving Frank and others donated land on 71st Street to become a Jewish campus. Now called the Zarrow Campus, it houses the Tulsa Jewish Federation offices, the Charles Schusterman Jewish Community Center, the Mizel Jewish Community Day School, the Sherwin Miller Jewish Museum, and the Tulsa Jewish Retirement and Health Center. In recent years, both congregations have remodeled their synagogues. In 2000, B’nai Emunah tore down its building, except for the sanctuary, and built a brand new synagogue around it. During the two years it took to complete the project, B’nai Emunah met at All Soul’s Unitarian Church. Temple Israel remodeled its 50 year-old building in 2005.

The Jewish Community in Tulsa Today

Temple Israel today. Photo courtesy of

Julian Preisler

.

Temple Israel today. Photo courtesy of

Julian Preisler

.

Despite wonderful facilities, the Jewish community of Tulsa is shrinking. According to current estimates, about 2,000 Jews live in Tulsa, down from 2,900 in 1984. About two-thirds of the Jewish children raised in Tulsa don’t come back after college; while the city continues to attract new Jewish families, they are unable to offset this loss. While it remains to be seen whether a shrinking community will be able to maintain the same institutional footprint, Tulsa’s Jewish institutions, especially its two congregations, remain strong.