Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Camden, South Carolina

Overview >> South Carolina >> Camden

Camden: Historical Overview

|

Camden, situated just east of the Wateree River, is the oldest inland town in South Carolina. Plans to establish a buffer town between Charles Towne and the backcountry were formulated in the 1730s. However, instead of occupying village lots, the early settlers spread out along the Wateree. Camden first appears in the records in 1768 when a court was established, and by 1785, there was evidence of an organized township.

Jews were living in Camden as early as the 1780s. The Jewish community lasts today. |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Camden

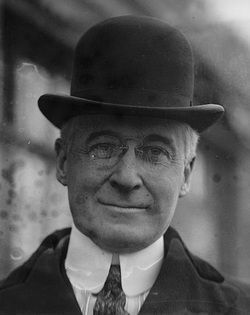

Chapman Levy,

ca. 1835

Chapman Levy,

ca. 1835

Early Settlers

The 1788 will of prominent businessman Joseph Kershaw provided Camden’s Jews with a plot of land on which to locate a synagogue and cemetery. Reportedly, the beneficiaries, who were not named, never claimed the land. In 1790, an estimated seven Jewish families resided in Camden. Chapman Levy, born into one of these families in 1787, became a successful lawyer, businessman, and politician. After spending his youth in nearby Columbia, he practiced law in his hometown, represented Kershaw County in the state house and senate, and serving as an officer in the militia during the War of 1812. He attended the 1832 Nullification Convention as an “ardent Union man.” In addition to practicing law, he owned a plantation, ran a brickyard, was an active Mason, and consulted with duelers regarding protocol. Levy owned 31 slaves, the largest number held by a Jew in South Carolina in the early 1800s.

Other Jewish residents of antebellum Camden included Dr. Abraham DeLeon, who moved his practice from Charleston in the second decade of the 19th century, and merchant and cotton factor Hayman Levy. Levy was active in the civic life of Camden, serving as warden in 1835, and intendant, or mayor, for the 1843-44 term. He also served as director of the Bank of Camden for 13 years, beginning in 1842. Mordecai Levy was in the pharmaceutical business with Abraham DeLeon, and was elected state legislator for Kershaw County for the years 1834-38. Chapman, Hayman, and Mordecai Levy were apparently not related. Other possibly Jewish names found in the records for Camden include Jacob DePass, Moses Sarzedas, Mordecai Lyon, Judah Barrett, and A. H. Davega. Despite their presence in Camden, no Jewish organizations were formed.

.

Camden may not have had enough Jewish residents at any one time during to support Jewish institutions in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Columbia’s proximity to Camden and its development as the state’s new capital after 1786 may have been a factor in limiting the growth and stability of Camden’s Jewish community during this period. About 30 miles from Camden, Columbia held great appeal for investors looking for new opportunities. Jews were among the Charleston and Camden men who moved to the burgeoning town. By 1826, 11 Columbia Jews had founded the Hebrew Benevolent Society, among them, Judah Barrett, who appears in the Camden records in 1832. Barrett served two terms as a warden in Columbia. Lax observance and assimilation may also have contributed to the absence of Jewish organizations in Camden. Chapman Levy, for example, helped to found the Camden Protestant Episcopal Church.

Based on brick-making, and flour, lumber, and textile mills, Camden's commerce prospered in the post-Revolutionary period. By 1800, cotton became the main cash crop in the district. The increase in trade made possible by the completion of a rail line connecting Camden to Charleston and Columbia in 1848 gave a significant boost to the local economy and paved the way for a permanent settlement of Jews.

The 1788 will of prominent businessman Joseph Kershaw provided Camden’s Jews with a plot of land on which to locate a synagogue and cemetery. Reportedly, the beneficiaries, who were not named, never claimed the land. In 1790, an estimated seven Jewish families resided in Camden. Chapman Levy, born into one of these families in 1787, became a successful lawyer, businessman, and politician. After spending his youth in nearby Columbia, he practiced law in his hometown, represented Kershaw County in the state house and senate, and serving as an officer in the militia during the War of 1812. He attended the 1832 Nullification Convention as an “ardent Union man.” In addition to practicing law, he owned a plantation, ran a brickyard, was an active Mason, and consulted with duelers regarding protocol. Levy owned 31 slaves, the largest number held by a Jew in South Carolina in the early 1800s.

Other Jewish residents of antebellum Camden included Dr. Abraham DeLeon, who moved his practice from Charleston in the second decade of the 19th century, and merchant and cotton factor Hayman Levy. Levy was active in the civic life of Camden, serving as warden in 1835, and intendant, or mayor, for the 1843-44 term. He also served as director of the Bank of Camden for 13 years, beginning in 1842. Mordecai Levy was in the pharmaceutical business with Abraham DeLeon, and was elected state legislator for Kershaw County for the years 1834-38. Chapman, Hayman, and Mordecai Levy were apparently not related. Other possibly Jewish names found in the records for Camden include Jacob DePass, Moses Sarzedas, Mordecai Lyon, Judah Barrett, and A. H. Davega. Despite their presence in Camden, no Jewish organizations were formed.

.

Camden may not have had enough Jewish residents at any one time during to support Jewish institutions in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Columbia’s proximity to Camden and its development as the state’s new capital after 1786 may have been a factor in limiting the growth and stability of Camden’s Jewish community during this period. About 30 miles from Camden, Columbia held great appeal for investors looking for new opportunities. Jews were among the Charleston and Camden men who moved to the burgeoning town. By 1826, 11 Columbia Jews had founded the Hebrew Benevolent Society, among them, Judah Barrett, who appears in the Camden records in 1832. Barrett served two terms as a warden in Columbia. Lax observance and assimilation may also have contributed to the absence of Jewish organizations in Camden. Chapman Levy, for example, helped to found the Camden Protestant Episcopal Church.

Based on brick-making, and flour, lumber, and textile mills, Camden's commerce prospered in the post-Revolutionary period. By 1800, cotton became the main cash crop in the district. The increase in trade made possible by the completion of a rail line connecting Camden to Charleston and Columbia in 1848 gave a significant boost to the local economy and paved the way for a permanent settlement of Jews.

Monument to

Marcus Baum

in the

Monument to

Marcus Baum

in the Hebrew Benevolent Cemetery.

The 19th Century

Three German Jewish brothers arrived in Camden in the years prior to the Civil War. Mannes, Herman, and Marcus Baum of Schwersenz, Prussia, immigrated to Camden where they peddled for a time before opening the Baum Brothers Store in 1850. Located on Main Street, the store sold food and dry goods. Simon Baruch, at age 15, left the same Prussian village in order to avoid conscription and joined the Baums in 1855. The Baruch and the Baum families may have been related. Mannes not only took Simon in, he sent him to medical school. In 1862, the newly graduated physician, out of a sense of loyalty to his adopted state, joined the Confederate Army as an assistant surgeon. His brother, Herman, who had followed him to Camden from Prussia, and the three Baums signed up as well. Marcus Baum was accidentally killed by Confederate fire and a monument in his memory was erected in the Hebrew Benevolent Society Cemetery.

After the war, Herman and Mannes Baum returned to Camden to reopen their store. Located on Broad Street, it became Camden’s largest mercantile business of its time. Herman gradually acquired land from farmers who owed the brothers money. Under the crop lien system, merchants accepted land as collateral in lieu of payment for goods purchased by the farmers who had no cash until the harvest. The next generation of Baums followed suit and became cotton planters and, for a time, the largest landholders in Kershaw County with three plantations.

Several other Jewish families made Camden their home. The Wittkowsky family, and possibly the Rich and the Wolfe families, had already settled in town prior to the Civil War. There town's general merchandisers, besides the Baum Brothers, included M.S. Bamberg, Herman Baruch, W. Geisenheimer, Hirsch Brothers & Block, A. Kahn, B. Rich, I. Rich, Bamberg & Rosenberger, JW Stein, Wolfe, S. & Son, and David Wolfe. The 1883 business directory lists Mrs. W. Geisenheimer as the purveyor of “fancy goods.” Geisenheimer & Watkins ran a grocery store and a saloon in 1883. By 1886, W. Geisenheimer and S. M. Rosenberger were running their own saloons. In 1890, M. Rich was selling clothing and L. A. Wittkowsky was practicing law. The 1900 directory reveals W. Geisenheimer had changed his profession from saloon keeper to owner of the Camden Furniture Store, and the town had a new dentist, A. Weinberg. Harry L. Schlosburg joined the dry goods and clothing competition with a store on Broad Street, and A. Wittkowsky sold groceries. Heyman’s Jewelers could also be found on Broad Street.

Three German Jewish brothers arrived in Camden in the years prior to the Civil War. Mannes, Herman, and Marcus Baum of Schwersenz, Prussia, immigrated to Camden where they peddled for a time before opening the Baum Brothers Store in 1850. Located on Main Street, the store sold food and dry goods. Simon Baruch, at age 15, left the same Prussian village in order to avoid conscription and joined the Baums in 1855. The Baruch and the Baum families may have been related. Mannes not only took Simon in, he sent him to medical school. In 1862, the newly graduated physician, out of a sense of loyalty to his adopted state, joined the Confederate Army as an assistant surgeon. His brother, Herman, who had followed him to Camden from Prussia, and the three Baums signed up as well. Marcus Baum was accidentally killed by Confederate fire and a monument in his memory was erected in the Hebrew Benevolent Society Cemetery.

After the war, Herman and Mannes Baum returned to Camden to reopen their store. Located on Broad Street, it became Camden’s largest mercantile business of its time. Herman gradually acquired land from farmers who owed the brothers money. Under the crop lien system, merchants accepted land as collateral in lieu of payment for goods purchased by the farmers who had no cash until the harvest. The next generation of Baums followed suit and became cotton planters and, for a time, the largest landholders in Kershaw County with three plantations.

Several other Jewish families made Camden their home. The Wittkowsky family, and possibly the Rich and the Wolfe families, had already settled in town prior to the Civil War. There town's general merchandisers, besides the Baum Brothers, included M.S. Bamberg, Herman Baruch, W. Geisenheimer, Hirsch Brothers & Block, A. Kahn, B. Rich, I. Rich, Bamberg & Rosenberger, JW Stein, Wolfe, S. & Son, and David Wolfe. The 1883 business directory lists Mrs. W. Geisenheimer as the purveyor of “fancy goods.” Geisenheimer & Watkins ran a grocery store and a saloon in 1883. By 1886, W. Geisenheimer and S. M. Rosenberger were running their own saloons. In 1890, M. Rich was selling clothing and L. A. Wittkowsky was practicing law. The 1900 directory reveals W. Geisenheimer had changed his profession from saloon keeper to owner of the Camden Furniture Store, and the town had a new dentist, A. Weinberg. Harry L. Schlosburg joined the dry goods and clothing competition with a store on Broad Street, and A. Wittkowsky sold groceries. Heyman’s Jewelers could also be found on Broad Street.

Simon Baruch returned to Camden after the Civil War and, in 1867, married Isabelle Wolfe. Isabelle’s ancestors were Sephardic Jews who had settled in the colonies in the 1690s. Her grandfather, Rabbi Hartwig Cohen of Charleston’s Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim, had married a member of the Marks (previously Marques) family. Simon established a private medical practice, often receiving payment in the form of goods and services. He served as the president of the South Carolina Medical Association and headed the State Board of Health. Determined to improve local farming techniques, he also conducted agricultural experiments on his three acres of land.

The Baruchs had four sons. Bernard, born in 1870, described his childhood impressions of Camden in his memoir, My Own Story. The town's two thousand people were divided fairly evenly between black and white residents. About 80 Jews lived in Camden, according to statistics for 1878. Bernard insisted there was no anti-Semitism and in fact, his father was a member of the Ku Klux Klan. At that time, he explained, the KKK’s reputation was that of a “heroic band fighting to free the South from the debaucheries of carpetbag rule.” Therefore, Bernard and his brothers were duly impressed upon discovering their father’s Klan robe and hood beneath his Confederate uniform in an attic trunk.

The Baruchs had four sons. Bernard, born in 1870, described his childhood impressions of Camden in his memoir, My Own Story. The town's two thousand people were divided fairly evenly between black and white residents. About 80 Jews lived in Camden, according to statistics for 1878. Bernard insisted there was no anti-Semitism and in fact, his father was a member of the Ku Klux Klan. At that time, he explained, the KKK’s reputation was that of a “heroic band fighting to free the South from the debaucheries of carpetbag rule.” Therefore, Bernard and his brothers were duly impressed upon discovering their father’s Klan robe and hood beneath his Confederate uniform in an attic trunk.

Hirsch

Brothers

Store

Hirsch

Brothers

Store

Organized Jewish Life in Camden

Bernard Baruch Bernard felt that Judaism did not set his family apart from the Christians of Camden, but rather the ”differences in religion bred a sense of mutual respect.” Isabelle set the example by insisting her boys wear their Sabbath clothes and be on their best behavior on Sundays. There was a division, however, in the existence of two rival gangs formed by the boys in town. Bernard and his brothers belonged to the “uptown” gang, distinguished in his memory from the “downtown” gang by the fact that they had to wash their feet every night. In retrospect, he realized that the rivalry was evidence of a social divide.

Isabelle, raised in a kosher home, directed her sons’ religious upbringing by conducting prayer sessions at home in lieu of synagogue services. Part of observing the Sabbath included confining the Baruch boys, dressed in their good clothes and even wearing shoes, to their own house and yard. Bernard and his brothers chafed under the restriction since Saturday, the day the farmers rode in from the country, was the most exciting day to be in town. Holiday observance was also Isabelle’s domain. Bernard noticed his father seemed less concerned with religious practices than his mother.

Nevertheless, Simon Baruch was one of about two dozen men who formed Camden’s Hebrew Benevolent Association in 1877. Other founding family names included Arnstein, Bamberg, Baum, Block, Eben, Hoffstadt, Jacobson, Kahn, Katz, Rich, Rosenberger, Simons, Smith, Strauss, Tobias, Williams, and Wittkowsky. In addition to “promoting Judaism,” the charitable organization’s objectives were to “visit the sick, relieve the distress, and bury the dead.” In December 1877, the group purchased land for a cemetery for $75.

Camden Jews were meeting for services in a room over a store. J. M. Williams, one of the founders of the Hebrew Benevolent Association, served as the lay reader at High Holy Days services in the years before his death in 1883. The Association’s charitable acts were not limited to Camden. Its members donated money to support the prosecution of a man accused of murdering a Jew in Abbeville. The group also sent money to Charleston twice in 1886, first in response to a request for aid for the Jewish victims of the August 31st earthquake, and second, to help rebuild the Orthodox synagogue Brith Sholom. Funds were also sent to help build and sustain an orphanage in Atlanta.

Under the leadership of Isabelle Baruch, the Association had opened a Sunday school by 1880 and secured Mary Williams of Charleston as instructor. References to a congregation, Gemilath Chasodim, or “Acts of Loving Kindness,” appear in 1880 as a potential source of funds for constructing a building for worship and education of its members. According to later members, the founders, and presumably the congregation, were Orthodox. However, it appears that they did not adhere strictly to the Orthodox tradition. In 1878, after some debate and upon Simon Baruch’s assertion that their constitution provided for the admission of “all Israelites,” the male membership agreed to admit its first female, Mrs. Benjamen, to the Association. In 1882, members held a special meeting to discuss joining the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, a Reform organization. The outcome of the discussion is unknown, although the first Reform services were not held until 1915, led by Rabbi Harry Merfeld of Columbia.

The Association lost its president, Simon Baruch, when he resigned both his post and his membership in late 1880. Isabelle had been encouraging Simon to move the family north in search of better opportunities when a tragic event prompted Simon’s decision to leave. Already disturbed by the violence in the state during Reconstruction, Simon was unprepared for the fatal outcome of a duel he had worked hard to derail. The Shannon-Cash duel precipitated the Baruch family’s move to New York in early 1881 and led to the passage of legislation outlawing dueling in South Carolina.

Simon’s devotion to the Camden Jewish community and his Jewish heritage is apparent in the advice he gave the members of the Association in a letter marking his departure. He urged belief in God and adherence to the “grand fundamental idea of Judaism.” Parents should assure their children become “useful citizens” through “proper religious instruction.” Therefore, it was essential to keep the Association active and to “build up the Sabbath school.”

Bernard Baruch Bernard felt that Judaism did not set his family apart from the Christians of Camden, but rather the ”differences in religion bred a sense of mutual respect.” Isabelle set the example by insisting her boys wear their Sabbath clothes and be on their best behavior on Sundays. There was a division, however, in the existence of two rival gangs formed by the boys in town. Bernard and his brothers belonged to the “uptown” gang, distinguished in his memory from the “downtown” gang by the fact that they had to wash their feet every night. In retrospect, he realized that the rivalry was evidence of a social divide.

Isabelle, raised in a kosher home, directed her sons’ religious upbringing by conducting prayer sessions at home in lieu of synagogue services. Part of observing the Sabbath included confining the Baruch boys, dressed in their good clothes and even wearing shoes, to their own house and yard. Bernard and his brothers chafed under the restriction since Saturday, the day the farmers rode in from the country, was the most exciting day to be in town. Holiday observance was also Isabelle’s domain. Bernard noticed his father seemed less concerned with religious practices than his mother.

Nevertheless, Simon Baruch was one of about two dozen men who formed Camden’s Hebrew Benevolent Association in 1877. Other founding family names included Arnstein, Bamberg, Baum, Block, Eben, Hoffstadt, Jacobson, Kahn, Katz, Rich, Rosenberger, Simons, Smith, Strauss, Tobias, Williams, and Wittkowsky. In addition to “promoting Judaism,” the charitable organization’s objectives were to “visit the sick, relieve the distress, and bury the dead.” In December 1877, the group purchased land for a cemetery for $75.

Camden Jews were meeting for services in a room over a store. J. M. Williams, one of the founders of the Hebrew Benevolent Association, served as the lay reader at High Holy Days services in the years before his death in 1883. The Association’s charitable acts were not limited to Camden. Its members donated money to support the prosecution of a man accused of murdering a Jew in Abbeville. The group also sent money to Charleston twice in 1886, first in response to a request for aid for the Jewish victims of the August 31st earthquake, and second, to help rebuild the Orthodox synagogue Brith Sholom. Funds were also sent to help build and sustain an orphanage in Atlanta.

Under the leadership of Isabelle Baruch, the Association had opened a Sunday school by 1880 and secured Mary Williams of Charleston as instructor. References to a congregation, Gemilath Chasodim, or “Acts of Loving Kindness,” appear in 1880 as a potential source of funds for constructing a building for worship and education of its members. According to later members, the founders, and presumably the congregation, were Orthodox. However, it appears that they did not adhere strictly to the Orthodox tradition. In 1878, after some debate and upon Simon Baruch’s assertion that their constitution provided for the admission of “all Israelites,” the male membership agreed to admit its first female, Mrs. Benjamen, to the Association. In 1882, members held a special meeting to discuss joining the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, a Reform organization. The outcome of the discussion is unknown, although the first Reform services were not held until 1915, led by Rabbi Harry Merfeld of Columbia.

The Association lost its president, Simon Baruch, when he resigned both his post and his membership in late 1880. Isabelle had been encouraging Simon to move the family north in search of better opportunities when a tragic event prompted Simon’s decision to leave. Already disturbed by the violence in the state during Reconstruction, Simon was unprepared for the fatal outcome of a duel he had worked hard to derail. The Shannon-Cash duel precipitated the Baruch family’s move to New York in early 1881 and led to the passage of legislation outlawing dueling in South Carolina.

Simon’s devotion to the Camden Jewish community and his Jewish heritage is apparent in the advice he gave the members of the Association in a letter marking his departure. He urged belief in God and adherence to the “grand fundamental idea of Judaism.” Parents should assure their children become “useful citizens” through “proper religious instruction.” Therefore, it was essential to keep the Association active and to “build up the Sabbath school.”

Camden-native

Bernard Baruch

Camden-native

Bernard Baruch

Bernard Baruch

Bernard Baruch proved to be a “useful citizen.” He earned his first million before the age of 30, became a successful Wall Street broker, advisor to several presidents, and a philanthropist whose generosity benefited South Carolinians, among others. A hospital in Camden opened in 1913 after Bernard donated $40,000 toward the renovation of the old Presbyterian Manse. When the hospital was destroyed in a 1921 fire, he contributed an additional $25,000 for the rebuilding effort.

Between 1905 and 1907, Bernard acquired more than 17,000 acres of former rice plantation lands northeast of Georgetown on the Waccamaw Neck between Winyah Bay and the Atlantic in an attempt to reconstruct the original king’s grant of Hobcaw Barony. Having visited relatives in Georgetown as a child, he was familiar with the area. His mother’s advice was influential in his decision to purchase property in South Carolina. She encouraged him to maintain a connection with his home state and assist in its “regeneration.” Specifically, she urged him to help black South Carolinians. He appeared to heed her advice, as he focused his charitable efforts on the black residents of Hobcaw and the state.

Bernard and his many famous guests used Hobcaw as a winter retreat. For the locals, Bernard’s ownership of the property was a boost to the economy. He employed around 100 workers, providing them with improved housing, education for their children, and medical care. His donations to South Carolina colleges and the scholarships he funded included both white and black institutions. His offer to pay the entire cost of construction of the new hospital in Camden was contingent upon their agreement that a number of beds would be set aside for black patients.

Bernard Baruch proved to be a “useful citizen.” He earned his first million before the age of 30, became a successful Wall Street broker, advisor to several presidents, and a philanthropist whose generosity benefited South Carolinians, among others. A hospital in Camden opened in 1913 after Bernard donated $40,000 toward the renovation of the old Presbyterian Manse. When the hospital was destroyed in a 1921 fire, he contributed an additional $25,000 for the rebuilding effort.

Between 1905 and 1907, Bernard acquired more than 17,000 acres of former rice plantation lands northeast of Georgetown on the Waccamaw Neck between Winyah Bay and the Atlantic in an attempt to reconstruct the original king’s grant of Hobcaw Barony. Having visited relatives in Georgetown as a child, he was familiar with the area. His mother’s advice was influential in his decision to purchase property in South Carolina. She encouraged him to maintain a connection with his home state and assist in its “regeneration.” Specifically, she urged him to help black South Carolinians. He appeared to heed her advice, as he focused his charitable efforts on the black residents of Hobcaw and the state.

Bernard and his many famous guests used Hobcaw as a winter retreat. For the locals, Bernard’s ownership of the property was a boost to the economy. He employed around 100 workers, providing them with improved housing, education for their children, and medical care. His donations to South Carolina colleges and the scholarships he funded included both white and black institutions. His offer to pay the entire cost of construction of the new hospital in Camden was contingent upon their agreement that a number of beds would be set aside for black patients.

Belle

Baruch

Belle

Baruch

Baruch Bernard’s eldest child, Belle, followed her father’s philanthropic lead. She purchased Hobcaw from him, and upon her death in 1964, the land was set aside as a protected wildlife refuge. Belle’s will assured Hobcaw would be held in a private trust, the Belle Baruch Foundation, for the benefit of South Carolina and its residents. The land and its resources are utilized for teaching and scientific research and the property is open to the public for guided tours.

Changes in the Community

Around the time the Baruchs moved north, wealthy Northerners began wintering in Camden. An 1888 pamphlet touts the area’s mild and “remarkably dry” climate as beneficial to those with pulmonary problems, nervous conditions, and insomnia. Now that a rail connection to New York was nearly complete and ties to the Great Lakes region were expected in a year or so, an increase in the number of visitors was anticipated. Equestrian sports such as polo became a big draw. Thus, the area’s economy, based primarily on farming, trading, and cotton mills, expanded to include tourism. By the second decade of the 20th century, Camden's economy began shifting from agriculture to manufacturing. The Duke Power Plant was built in 1919 on the Wateree River, paving the way for new industries to locate their plants in the area. DuPont came in 1949.

Changes in the Community

Around the time the Baruchs moved north, wealthy Northerners began wintering in Camden. An 1888 pamphlet touts the area’s mild and “remarkably dry” climate as beneficial to those with pulmonary problems, nervous conditions, and insomnia. Now that a rail connection to New York was nearly complete and ties to the Great Lakes region were expected in a year or so, an increase in the number of visitors was anticipated. Equestrian sports such as polo became a big draw. Thus, the area’s economy, based primarily on farming, trading, and cotton mills, expanded to include tourism. By the second decade of the 20th century, Camden's economy began shifting from agriculture to manufacturing. The Duke Power Plant was built in 1919 on the Wateree River, paving the way for new industries to locate their plants in the area. DuPont came in 1949.

Photo

by

Bill Aron

Photo

by

Bill Aron

Temple Beth El

At some point early in its history, the Hebrew Benevolent Association acquired an empty lot on DeKalb Street. Debate over its use went on for years and it appears that ultimately it was sold. In 1921, the Association finally settled on a plan for a house of worship and purchased a building, a former Catholic church. The congregation, now called Temple Beth El, was served for nearly a decade by Rabbi F. Hirsch of Sumter. For many years, Sumter rabbis continued to travel to Camden twice a month to lead services on Sundays. The Sunday school was not always operational. Jewish children received some education in Camden, but also went to Sumter for confirmation classes at the Reform Temple Sinai. Some of Camden’s boys were bar mitzvahed. The Hebrew Men’s Club and the Sisterhood joined their national affiliates in 1928 and carried out the responsibilities of the Hebrew Benevolent Association.

The Interwar Years

By 1927, Camden’s Jewish population had grown to a little over one hundred. The Babin, Briskin, Eichel, Karesh, Lomansky, and Wallnau families contributed to the increase. In terms of size and participation, the Jewish community appears to have peaked between the world wars. The members of the generation growing up in this period, like their parents and grandparents, were integral members of the larger Camden community. They socialized with Jews and non-Jews alike, and participated in programs sponsored by Christian youth groups. Many of the Jewish youngsters felt they were no different from their Christian friends; they simply attended a different “church.” They reported being unfamiliar with Orthodox practices, such as the dietary restrictions or the use of a prayer shawl. Yet, their families celebrated all the major Jewish holidays.

By the 1950s, the Camden Jewish community had declined drastically. As early as 1937, the population estimate of 67 demonstrates a dramatic drop in just one decade. By mid-century, membership at Temple Beth El was down to 20 or 25. Despite dwindling numbers, the congregation raised enough money to build a hall in 1960. Located behind the Temple, the building became a venue for social events and Sunday school classes. Still, some children traveled to Columbia and Sumter for education and confirmation. In the post–World War II decades, the congregation was served on Sundays by Sumter Rabbis Aaron Levy and Avshalom Magidovitch. Members Leon Schlosburg, Jay Tanzer, and Bernard Baum served as lay readers.

At some point early in its history, the Hebrew Benevolent Association acquired an empty lot on DeKalb Street. Debate over its use went on for years and it appears that ultimately it was sold. In 1921, the Association finally settled on a plan for a house of worship and purchased a building, a former Catholic church. The congregation, now called Temple Beth El, was served for nearly a decade by Rabbi F. Hirsch of Sumter. For many years, Sumter rabbis continued to travel to Camden twice a month to lead services on Sundays. The Sunday school was not always operational. Jewish children received some education in Camden, but also went to Sumter for confirmation classes at the Reform Temple Sinai. Some of Camden’s boys were bar mitzvahed. The Hebrew Men’s Club and the Sisterhood joined their national affiliates in 1928 and carried out the responsibilities of the Hebrew Benevolent Association.

The Interwar Years

By 1927, Camden’s Jewish population had grown to a little over one hundred. The Babin, Briskin, Eichel, Karesh, Lomansky, and Wallnau families contributed to the increase. In terms of size and participation, the Jewish community appears to have peaked between the world wars. The members of the generation growing up in this period, like their parents and grandparents, were integral members of the larger Camden community. They socialized with Jews and non-Jews alike, and participated in programs sponsored by Christian youth groups. Many of the Jewish youngsters felt they were no different from their Christian friends; they simply attended a different “church.” They reported being unfamiliar with Orthodox practices, such as the dietary restrictions or the use of a prayer shawl. Yet, their families celebrated all the major Jewish holidays.

By the 1950s, the Camden Jewish community had declined drastically. As early as 1937, the population estimate of 67 demonstrates a dramatic drop in just one decade. By mid-century, membership at Temple Beth El was down to 20 or 25. Despite dwindling numbers, the congregation raised enough money to build a hall in 1960. Located behind the Temple, the building became a venue for social events and Sunday school classes. Still, some children traveled to Columbia and Sumter for education and confirmation. In the post–World War II decades, the congregation was served on Sundays by Sumter Rabbis Aaron Levy and Avshalom Magidovitch. Members Leon Schlosburg, Jay Tanzer, and Bernard Baum served as lay readers.

The Jewish Community in Camden Today

Allan Sindler

with his sculpture

Allan Sindler

with his sculpture

outside of Temple Beth El

Camden itself remains a small but vital industrial and equestrian community with a diverse population. Yet, for more than a decade, Temple Beth El’s congregation has been barely holding on with about six member-families. There are other Jews in town who do not join them either because they are not practicing Jews, or they prefer to attend services in Columbia or Sumter. Over the years, intermarriage and assimilation have taken their toll on the Jewish population. Rabbi-led services at the Temple are a thing of the past, as are regular weekly services. Garry Baum, Bernard's son, serves as lay reader for High Holy Days services. The small congregation, led by Barbara Freed-James, continues to maintain the cemetery and the Temple. Adorning Beth El ’s front lawn is a sculpture created by Allan Sindler who grew up in nearby Bishopville and raised his family in Camden. It is a double Star of David, an enduring symbol of Jewish identity representing God's protection.