Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Charleston, South Carolina

Overview >> South Carolina >> Charleston

Charleston: Historical Overview

|

The early years of America’s Jewish history were played out in a handful of port cities; among the foremost was Charleston, South Carolina. Jewish immigrants from England and the West Indies were drawn to South Carolina’s largest city as it became a transatlantic trading center for the Southern colonies. As late as 1820, Charleston was home to the largest Jewish community in the United States, and would soon become a pioneer in Reform Judaism. But just as Charleston was outpaced by other port cities like New York and New Orleans, its Jewish population failed to match the explosive growth of other Jewish communities in the South and the rest of the United States. While Charleston was no longer a major site in the history of American Jews, it remained a center of Jewish life in South Carolina and the Southeast.

|

RESOURCES

BSBI Synagogue website KKBE Synagogue website Synagogue Emanu-El website All photos courtesy of Special Collections, College of Charleston |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Charleston

Diorama depicting Francis Salvador's death

Diorama depicting Francis Salvador's death

Traders and Patriots: 1695-1820

Established by English settlers on the banks of the Ashley River in 1670, Charles Town soon became the capital of the Carolina colony and a bustling trading hub for the colony’s staple crop, rice. Charles Town also benefited as the closest major port to the colonial West Indies. The first record of a Jew living in Charles Town comes from 1695, when an official who worked for the colonial governor as a Spanish translator was identified as Jewish. In contrast to many other English colonies, Jews were welcomed in South Carolina. By 1700, a small number of Jewish merchants were living in Charles Town; they had become British subjects and were able to own land. Most of these Jewish settlers came from England or the British colonies in the West Indies. The Jewish population of Charles Town remained small; by the 1730s, there were only about ten Jewish households in the city.

According to the historian Jacob Rader Marcus, “Charleston Jewry came into its own in the 1740s” as Jews from New York, Savannah, London, and the West Indies streamed into the Carolina capital. By the mid-18th century, Charles Town’s port rivaled New York’s as the busiest in North America. Charles Town would flourish even more after indigo, a plant that produces a blue dye, became a second staple crop for the colony thanks to the efforts of a Jewish indigo expert. Once Carolina planters began to harvest indigo, Moses Lindo, a respected London merchant who dealt in the crop, decided to move to the colonies to help nurture the budding trade. Arriving in 1756, Lindo soon became the surveyor and inspector-general of indigo at the port of Charles Town. Lindo would grade each batch of indigo before it was shipped to England. Due to his reputation, Lindo’s grade carried a great deal of weight with the traders of London. His assessments sometimes angered local planters, and Lindo would often defend his reputation in Charles Town’s newspapers.

Charles Town’s Jewish community grew along with the city. In 1749, there were enough Jews to form a congregation, which they named Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim (Holy Community of the House of God); it was the fourth Jewish congregation founded in what would become the United States. Joseph Tobias was its first president while Isaac Da Costa was the first chazzan (service leader). Both men were merchants in Charles Town. In 1764, the congregation bought land for a Jewish cemetery. Although only about half of the founders were Sephardic in origin, the congregation, influenced by Congregation Shearith Israel in New York and the Bevis Marks Synagogue in London, chose the Sephardic rite for its worship style. For their first few decades, the small group met in private homes. By 1780, they had rented a brick building for use as a synagogue.

By the time of the American Revolution, about 200 Jews lived in Charles Town. Most of them supported the patriot cause since they enjoyed greater religious and political freedom in the colonies than they had in England. Francis Salvador embraced these freedoms and became a staunch defender of independence. The nephew of a wealthy merchant in London, Salvador came to South Carolina in 1773. By 1774, he had become a planter, acquiring land and thirty slaves. Although he had only recently lived in England, Salvador was a strong supporter of the colonists’ cause. He became a propagandist, traveling around the colony trying to convince farmers to support the colonies in their dispute with Mother England. He was chosen to serve in the first provisional congress in South Carolina in 1774; he remained in the state’s assembly after it had declared independence, helping to draft South Carolina’s constitution. Salvador was the first practicing Jew to serve in a legislative body in America. When fighting broke out in South Carolina in 1776, the 29-year-old Salvador joined the local militia, but was soon killed by British-allied Indians. In City Hall Park in downtown Charleston, there is a memorial plaque for Salvador, which reads “An Englishman, he cast his lot with America; True to his ancient faith, he gave his life for new hopes of human liberty and understanding.”

Established by English settlers on the banks of the Ashley River in 1670, Charles Town soon became the capital of the Carolina colony and a bustling trading hub for the colony’s staple crop, rice. Charles Town also benefited as the closest major port to the colonial West Indies. The first record of a Jew living in Charles Town comes from 1695, when an official who worked for the colonial governor as a Spanish translator was identified as Jewish. In contrast to many other English colonies, Jews were welcomed in South Carolina. By 1700, a small number of Jewish merchants were living in Charles Town; they had become British subjects and were able to own land. Most of these Jewish settlers came from England or the British colonies in the West Indies. The Jewish population of Charles Town remained small; by the 1730s, there were only about ten Jewish households in the city.

According to the historian Jacob Rader Marcus, “Charleston Jewry came into its own in the 1740s” as Jews from New York, Savannah, London, and the West Indies streamed into the Carolina capital. By the mid-18th century, Charles Town’s port rivaled New York’s as the busiest in North America. Charles Town would flourish even more after indigo, a plant that produces a blue dye, became a second staple crop for the colony thanks to the efforts of a Jewish indigo expert. Once Carolina planters began to harvest indigo, Moses Lindo, a respected London merchant who dealt in the crop, decided to move to the colonies to help nurture the budding trade. Arriving in 1756, Lindo soon became the surveyor and inspector-general of indigo at the port of Charles Town. Lindo would grade each batch of indigo before it was shipped to England. Due to his reputation, Lindo’s grade carried a great deal of weight with the traders of London. His assessments sometimes angered local planters, and Lindo would often defend his reputation in Charles Town’s newspapers.

Charles Town’s Jewish community grew along with the city. In 1749, there were enough Jews to form a congregation, which they named Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim (Holy Community of the House of God); it was the fourth Jewish congregation founded in what would become the United States. Joseph Tobias was its first president while Isaac Da Costa was the first chazzan (service leader). Both men were merchants in Charles Town. In 1764, the congregation bought land for a Jewish cemetery. Although only about half of the founders were Sephardic in origin, the congregation, influenced by Congregation Shearith Israel in New York and the Bevis Marks Synagogue in London, chose the Sephardic rite for its worship style. For their first few decades, the small group met in private homes. By 1780, they had rented a brick building for use as a synagogue.

By the time of the American Revolution, about 200 Jews lived in Charles Town. Most of them supported the patriot cause since they enjoyed greater religious and political freedom in the colonies than they had in England. Francis Salvador embraced these freedoms and became a staunch defender of independence. The nephew of a wealthy merchant in London, Salvador came to South Carolina in 1773. By 1774, he had become a planter, acquiring land and thirty slaves. Although he had only recently lived in England, Salvador was a strong supporter of the colonists’ cause. He became a propagandist, traveling around the colony trying to convince farmers to support the colonies in their dispute with Mother England. He was chosen to serve in the first provisional congress in South Carolina in 1774; he remained in the state’s assembly after it had declared independence, helping to draft South Carolina’s constitution. Salvador was the first practicing Jew to serve in a legislative body in America. When fighting broke out in South Carolina in 1776, the 29-year-old Salvador joined the local militia, but was soon killed by British-allied Indians. In City Hall Park in downtown Charleston, there is a memorial plaque for Salvador, which reads “An Englishman, he cast his lot with America; True to his ancient faith, he gave his life for new hopes of human liberty and understanding.”

Portrait of Abraham Mendes Seixas,

ca. 1795

Portrait of Abraham Mendes Seixas,

ca. 1795

During the Revolution, many of the young Jewish men of Charles Town fought for independence. In fact, so many Jews served in a particular company in the Charles Town Regiment, perhaps as many as 28, that it became known informally as the “Jew Company.” These companies were formed based on where the men lived, and since so many Jews lived around King Street, most ended up in the same company. Abraham Mendes Seixas was born in New York but moved to Charles Town in 1774. When the war broke out, he became a captain of a Charles Town militia company. After the city was captured by the British, Seixas was banished from Charles Town when he refused to sign a loyalty oath. Seixas went to Philadelphia and was soon followed by many other Charles Town Jews who were seeking to escape British control. After the war, Seixas and other Jews returned to the city that was now known as Charleston.

Charleston became a thriving trading center after the war, and its Jewish population grew to an estimated 500 by the turn of the 19th century as Jews from England, Central Europe, and other American cities came to Charleston. Most were involved in commercial trade. One study found that 40% of Jewish breadwinners in Charleston were listed as “shopkeeper” in the 1801 city directory; 20% were merchants, while 22% were brokers and auctioneers. Merchants had larger businesses than shopkeepers. Most of these Jewish stores were centered around King Street and sold a variety of merchandise.

Interestingly, a handful of these businesses were run by women who had been given “sole trader” status by their husbands. Under coverture laws, married women were the legal property of their husbands, although they could be granted independent economic status by their husbands through a legal document. The historian James Hagy found 48 Jewish women who were classified as “sole traders” between 1766 and 1827, many of whom helped run their husbands' businesses when the men were away. In other instances, a woman would take over the family business from her husband when it was not doing well. Rebecca De Mendes Benjamin, the mother of future Confederate leader Judah P. Benjamin, was given sole trader status by her husband when his dry goods store was in dire financial straits. Rebecca took over the business. Later, she owned a store in Beaufort while her husband remained in Charleston. In a few instances, these women were able to pass their businesses down to their children. Hannah Hyams owned a dry goods store on King Street in the first decade of the 19th century; she later transferred the business to Judith Hyams, who was either her daughter or daughter-in-law.

Charleston became a thriving trading center after the war, and its Jewish population grew to an estimated 500 by the turn of the 19th century as Jews from England, Central Europe, and other American cities came to Charleston. Most were involved in commercial trade. One study found that 40% of Jewish breadwinners in Charleston were listed as “shopkeeper” in the 1801 city directory; 20% were merchants, while 22% were brokers and auctioneers. Merchants had larger businesses than shopkeepers. Most of these Jewish stores were centered around King Street and sold a variety of merchandise.

Interestingly, a handful of these businesses were run by women who had been given “sole trader” status by their husbands. Under coverture laws, married women were the legal property of their husbands, although they could be granted independent economic status by their husbands through a legal document. The historian James Hagy found 48 Jewish women who were classified as “sole traders” between 1766 and 1827, many of whom helped run their husbands' businesses when the men were away. In other instances, a woman would take over the family business from her husband when it was not doing well. Rebecca De Mendes Benjamin, the mother of future Confederate leader Judah P. Benjamin, was given sole trader status by her husband when his dry goods store was in dire financial straits. Rebecca took over the business. Later, she owned a store in Beaufort while her husband remained in Charleston. In a few instances, these women were able to pass their businesses down to their children. Hannah Hyams owned a dry goods store on King Street in the first decade of the 19th century; she later transferred the business to Judith Hyams, who was either her daughter or daughter-in-law.

Interior of Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim, 1838,

Interior of Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim, 1838,

by Solomon Carvalho

The flourishing of the Charleston Jewish community after the American Revolution benefited Beth Elohim. In 1791, the congregation, which now numbered 53 families, purchased land for its first permanent synagogue. The city’s first Jewish house of worship was completed in 1794. The synagogue’s architecture was symbolic of Charleston’s Jewish community. From the outside, the building did not look much different from a Christian church, but on the inside, the sanctuary was laid out in the traditional manner of Sephardic ritual. The reading platform was in the middle of the floor facing the ark and there was a separate balcony for women. While Charleston Jews fit well into the local society and economy, they still maintained their Orthodox Judaism.

The growth of Beth Elohim occurred in the rich soil of post-Revolutionary America, in which Jews had been given equal rights, for the first time in recent world history. When the synagogue was completed, a local newspaper praised the new building and celebrated the freedom Jews enjoyed in Charleston, writing that, “the shackles of religious distinctions are now no more…they [Jews] are here admitted to the full privileges of citizenship and bid fair to flourish and be happy.” Indeed, South Carolina’s 1790 constitution guaranteed religious liberty in the state and gave Jewish men the right to vote and hold office. Abraham Mendes Seixas served as a city magistrate after the Revolution. Charleston Jews reveled in their freedoms. In 1806, they wrote to London’s Sephardic synagogue looking for a new chazzan to lead services. In the letter, the congregation described life in the early republic for Jews, “in a free and independent country like America…, where in short we enjoy all the blessings of freedom in common with our fellow citizens, you may readily conceive we pride ourselves under the happy situation which makes us feel we are men.”

The growth of Beth Elohim occurred in the rich soil of post-Revolutionary America, in which Jews had been given equal rights, for the first time in recent world history. When the synagogue was completed, a local newspaper praised the new building and celebrated the freedom Jews enjoyed in Charleston, writing that, “the shackles of religious distinctions are now no more…they [Jews] are here admitted to the full privileges of citizenship and bid fair to flourish and be happy.” Indeed, South Carolina’s 1790 constitution guaranteed religious liberty in the state and gave Jewish men the right to vote and hold office. Abraham Mendes Seixas served as a city magistrate after the Revolution. Charleston Jews reveled in their freedoms. In 1806, they wrote to London’s Sephardic synagogue looking for a new chazzan to lead services. In the letter, the congregation described life in the early republic for Jews, “in a free and independent country like America…, where in short we enjoy all the blessings of freedom in common with our fellow citizens, you may readily conceive we pride ourselves under the happy situation which makes us feel we are men.”

Official seal of the Hebrew Benevolent Society

Official seal of the Hebrew Benevolent Society

After the Revolution, Charleston Jews began to form institutions to take care of the members of their community in financial need. In 1784, they founded the Hebrew Benevolent Society to help sick Jewish immigrants in the city. In 1824, the group expanded its mission to help the poor and bury the dead; they would buy heating fuel and Passover matzos for those Jews who could not afford them. After Charleston suffered a major earthquake in 1886, the Hebrew Benevolent Society raised over $4000 from Jewish communities across the country to help care for Charleston Jews in need. In 1801, Jews founded the Hebrew Orphan Society, which helped the children of dead or indigent parents. In 1851, the Orphan Society started a Hebrew school to educate their wards. On the eve of the Civil War, the group converted their office building into an orphanage. Once the war broke out, the orphanage was closed; later, the society began to support the B’nai B’rith Orphans Home in Atlanta. Since 1900 or so, membership has been limited to 18 people, with memberships being passed down from generation to generation within Charleston’s old Jewish families. Both the Orphan Society and the Hebrew Benevolent Society still serve the Charleston Jewish community today.

In the warm glow of freedom during the Early Republic period, Charleston’s Jewish community flourished. By 1820, 700 Jews lived in Charleston, more than any other American city. Jews made up 5% of Charleston’s white population. Yet 1820 marked the apex of Charleston’s place in American Jewish history. Soon after, the city was outpaced by other port cities like New Orleans and New York. By 1840, more exports came out of the port of Mobile, Alabama than that of Charleston. Charleston did not grow into a major city like the other colonial port settlements such as New York, Boston, and Philadelphia. When large waves of Jewish immigrants from central Europe began to arrive in the United States in the 1820s, most settled in these northeastern cities. By 1860, New York had 40,000 Jews while Charleston’s Jewish population remained at 700.

In the warm glow of freedom during the Early Republic period, Charleston’s Jewish community flourished. By 1820, 700 Jews lived in Charleston, more than any other American city. Jews made up 5% of Charleston’s white population. Yet 1820 marked the apex of Charleston’s place in American Jewish history. Soon after, the city was outpaced by other port cities like New Orleans and New York. By 1840, more exports came out of the port of Mobile, Alabama than that of Charleston. Charleston did not grow into a major city like the other colonial port settlements such as New York, Boston, and Philadelphia. When large waves of Jewish immigrants from central Europe began to arrive in the United States in the 1820s, most settled in these northeastern cities. By 1860, New York had 40,000 Jews while Charleston’s Jewish population remained at 700.

Civil Wars in Charleston: 1821-1865

As Charleston’s economic prominence faded, Jews were part of a wave of South Carolinians who left the state for greater opportunities in the Deep South. Several of these Charleston-born Jews went on to have illustrious careers in other places. Philip Phillips became a U.S. Congressman from Mobile, Henry Hyams was elected as Louisiana’s Lieutenant Governor, while Judah P. Benjamin served in the U.S. Senate before becoming a cabinet officer in the Confederate government.

Of those Jews who remained in Charleston, many were native-born and began to worry that Beth Elohim was too traditional to fit into America’s environment of religious and political freedom. According to the historian Jonathan Sarna, like the other Jewish congregations in the United States at the time, Beth Elohim was a “synagogue-community” in which there was no distinction between the congregation and the Jewish community. All Jews over 21 years of age were expected to be members of the city’s only synagogue. If one had recently moved to Charleston, he was expected to join Beth Elohim within a certain amount of time or would be fined and banned from joining in the future. The congregation tried to regulate the behavior of its members. Rules enforced Sabbath observance and outlawed intermarriage. Members were not allowed to form another congregation; if they did, they would be fined and kicked out of the congregation and its cemetery forever. Members were routinely fined for several lesser offenses. Like all other synagogues in the United States in this period, Beth Elohim was strictly Orthodox.

As Charleston’s economic prominence faded, Jews were part of a wave of South Carolinians who left the state for greater opportunities in the Deep South. Several of these Charleston-born Jews went on to have illustrious careers in other places. Philip Phillips became a U.S. Congressman from Mobile, Henry Hyams was elected as Louisiana’s Lieutenant Governor, while Judah P. Benjamin served in the U.S. Senate before becoming a cabinet officer in the Confederate government.

Of those Jews who remained in Charleston, many were native-born and began to worry that Beth Elohim was too traditional to fit into America’s environment of religious and political freedom. According to the historian Jonathan Sarna, like the other Jewish congregations in the United States at the time, Beth Elohim was a “synagogue-community” in which there was no distinction between the congregation and the Jewish community. All Jews over 21 years of age were expected to be members of the city’s only synagogue. If one had recently moved to Charleston, he was expected to join Beth Elohim within a certain amount of time or would be fined and banned from joining in the future. The congregation tried to regulate the behavior of its members. Rules enforced Sabbath observance and outlawed intermarriage. Members were not allowed to form another congregation; if they did, they would be fined and kicked out of the congregation and its cemetery forever. Members were routinely fined for several lesser offenses. Like all other synagogues in the United States in this period, Beth Elohim was strictly Orthodox.

Silhouette of Isaac Harby,

from "The Jews of Charleston,"

by Charles Reznikoff

Silhouette of Isaac Harby,

from "The Jews of Charleston,"

by Charles Reznikoff

This European-style of the Jewish synagogue-community could not long survive the freedoms unleashed by the American Revolution. By the 1820s, many of Beth Elohim’s members, like Isaac Harby, were native-born and thoroughly assimilated. Harby was born in Charleston in 1788 and worked as an educator, playwright, and journalist. Harby feared that Beth Elohim’s style of Orthodox worship did not resonate with native-born Jews like himself, many of whom did not understand Hebrew. Harby felt that if Judaism did not change, it would not survive in America due to the growing “apathy and neglect which have been manifested towards our holy religion.” To combat this challenge, Harby and a group of 46 other Charleston Jews called for a style of worship that was more like that of their Gentile neighbors.

In 1824, these 47 Charleston Jews, two-thirds of whom were native-born, submitted a petition to Beth Elohim’s leadership decrying the lack of decorum during services and calling for English sermons, shorter services, and less Hebrew and more English so members could better understand the prayers. The average age of the petitioners was 32 while that of Beth Elohim’s leadership was 62. The congregation’s leaders dismissed the petition out of hand since it did not follow Beth Elohim’s strict procedures for amending the constitution. Twelve members of the petitioning group, including its leaders Isaac Harby and Abraham Moise, decided to break away from Beth Elohim to form their own congregation, which they named “The Reformed Society of Israelites.”

This new congregation soon attracted many other members; by 1826, the society had 50 members, while Beth Elohim’s numbers had dropped to only 70. The Reformed Society soon moved away from strictly ritual issues, adopting a philosophical critique of Rabbinic Judaism that rejected Talmudic law as unsuited to the modern world. The group dispensed with head coverings and added musical instruments to their services. Their bylaws did not ban intermarried Jews from membership. The group put together their own prayer book, which became the first Reform prayer book ever written in America. Women were given a more prominent role in the Society. The Society’s prayer book gave brides a speaking part for the first time in Jewish wedding liturgy, included a new naming ceremony for baby girls, and even contained prayers written by Caroline Harby, Isaac’s sister.

In 1824, these 47 Charleston Jews, two-thirds of whom were native-born, submitted a petition to Beth Elohim’s leadership decrying the lack of decorum during services and calling for English sermons, shorter services, and less Hebrew and more English so members could better understand the prayers. The average age of the petitioners was 32 while that of Beth Elohim’s leadership was 62. The congregation’s leaders dismissed the petition out of hand since it did not follow Beth Elohim’s strict procedures for amending the constitution. Twelve members of the petitioning group, including its leaders Isaac Harby and Abraham Moise, decided to break away from Beth Elohim to form their own congregation, which they named “The Reformed Society of Israelites.”

This new congregation soon attracted many other members; by 1826, the society had 50 members, while Beth Elohim’s numbers had dropped to only 70. The Reformed Society soon moved away from strictly ritual issues, adopting a philosophical critique of Rabbinic Judaism that rejected Talmudic law as unsuited to the modern world. The group dispensed with head coverings and added musical instruments to their services. Their bylaws did not ban intermarried Jews from membership. The group put together their own prayer book, which became the first Reform prayer book ever written in America. Women were given a more prominent role in the Society. The Society’s prayer book gave brides a speaking part for the first time in Jewish wedding liturgy, included a new naming ceremony for baby girls, and even contained prayers written by Caroline Harby, Isaac’s sister.

Portrait of Abraham Moise, ca. 1790

Portrait of Abraham Moise, ca. 1790

The Reformed Society met in a local Masonic Hall and began to raise money to build what it called a “temple.” This initial enthusiasm eventually waned and the group disbanded in 1833. Most of the society’s members rejoined Beth Elohim, where they were welcomed back after paying a fine. If these reformers lost this battle, they soon won the war, as Beth Elohim began to embrace the principles and practices of Reform Judaism. Abraham Moise, who had been a leader of the Reformed Society, helped to write Beth Elohim’s new constitution in 1836, which incorporated such ritual changes as English sermons. The congregation established a religious school in 1838, only the second Jewish congregation in the United States to do so. They used lesson plans written by the pioneer Jewish educator Rebecca Gratz of Philadelphia.

Beth Elohim also hired a new chazzan who would push the congregation toward additional reforms but would also split the congregation once again. Gustavus Poznanski was born in Poland and spent time at the leading Reform congregation in Hamburg. He came to Beth Elohim in 1836 after working at Shearith Israel in New York as a shochet (kosher butcher) and occasional chazzan. In 1838, the synagogue burned down in one of the great fires that periodically swept the city. The congregation quickly began to design and build a new synagogue. While the synagogue was being rebuilt on the same site, a group of members petitioned for an organ to be included in the sanctuary, believing that it offered a more refined and spiritually uplifting tone to services. Since playing an organ on the Sabbath was prohibited by traditional Jewish law, the board of Beth Elohim rejected the petition. But at an all-congregation meeting, the issue was put to a vote and was approved 46 to 40, with Poznanski supporting the change. At the dedication of Beth Elohim’s rebuilt synagogue, Poznanski defended the organ and the increased use of English during services before famously declaring, “this synagogue is our temple, this city our Jerusalem, this happy land our Palestine.” According to Poznanski, Charleston Jews would no longer look toward the coming of the messiah and the reestablishment of the Temple in Jerusalem.

The traditionalists at Beth Elohim were extremely unhappy with the organ, and 40 of them broke off to form a new congregation, which they named Shearith Israel. Even after this schism, Beth Elohim continued to fight over issues of religious reform. In 1843, Poznanski declared that Jewish holidays did not need to be celebrated over two days, as was traditional. Beth Elohim’s board opposed this change and Poznanski agreed not to preach Reform without their approval. A traditional faction remained a part of Beth Elohim, and they pushed to have the members of Shearith Israel readmitted to the congregation. When the board president opposed this and refused to call a board meeting to discuss it, a rump group of board members called a meeting and voted to welcome back the members of Shearith Israel. The dispute ended up in court; after three years, the court finally ruled that it had no jurisdiction over the internal affairs of a religious congregation. The Jewish community of Charleston would remain split into two congregations. Shearith Israel, which had 56 member families, built their own synagogue in 1847.

Beth Elohim also hired a new chazzan who would push the congregation toward additional reforms but would also split the congregation once again. Gustavus Poznanski was born in Poland and spent time at the leading Reform congregation in Hamburg. He came to Beth Elohim in 1836 after working at Shearith Israel in New York as a shochet (kosher butcher) and occasional chazzan. In 1838, the synagogue burned down in one of the great fires that periodically swept the city. The congregation quickly began to design and build a new synagogue. While the synagogue was being rebuilt on the same site, a group of members petitioned for an organ to be included in the sanctuary, believing that it offered a more refined and spiritually uplifting tone to services. Since playing an organ on the Sabbath was prohibited by traditional Jewish law, the board of Beth Elohim rejected the petition. But at an all-congregation meeting, the issue was put to a vote and was approved 46 to 40, with Poznanski supporting the change. At the dedication of Beth Elohim’s rebuilt synagogue, Poznanski defended the organ and the increased use of English during services before famously declaring, “this synagogue is our temple, this city our Jerusalem, this happy land our Palestine.” According to Poznanski, Charleston Jews would no longer look toward the coming of the messiah and the reestablishment of the Temple in Jerusalem.

The traditionalists at Beth Elohim were extremely unhappy with the organ, and 40 of them broke off to form a new congregation, which they named Shearith Israel. Even after this schism, Beth Elohim continued to fight over issues of religious reform. In 1843, Poznanski declared that Jewish holidays did not need to be celebrated over two days, as was traditional. Beth Elohim’s board opposed this change and Poznanski agreed not to preach Reform without their approval. A traditional faction remained a part of Beth Elohim, and they pushed to have the members of Shearith Israel readmitted to the congregation. When the board president opposed this and refused to call a board meeting to discuss it, a rump group of board members called a meeting and voted to welcome back the members of Shearith Israel. The dispute ended up in court; after three years, the court finally ruled that it had no jurisdiction over the internal affairs of a religious congregation. The Jewish community of Charleston would remain split into two congregations. Shearith Israel, which had 56 member families, built their own synagogue in 1847.

Portrait of Penina Moise

Portrait of Penina Moise

Beth Elohim continued to embrace religious reform. Penina Moise, the sister of Abraham, was an accomplished poet who wrote English hymns that were used during Beth Elohim’s worship service. Beth Elohim published a hymnal in 1842; 60 of its 74 songs were penned by Moise. Her hymns were later adopted by Reform congregations across the country. When Poznanski left Beth Elohim in 1847, they offered their pulpit to Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, who would soon become the founding father of the Reform Movement in America. When Wise turned down the position, they hired Julius Eckman, though he was soon fired after he tried to reimpose traditional worship. In 1852, Beth Elohim held its first confirmation ceremony, a ritual which had been borrowed from Christianity.

Although Charleston Jews were bitterly divided over how best to worship God, they were unified on the issue of the country’s growing sectional conflict. Charleston Jews had become well integrated in the city’s economic, political, and social life. Jacob De La Motta, an active leader of Beth Elohim, was a physician who was elected as secretary of the local medical society in 1824. Abraham Moise was a lawyer who served as a local magistrate from 1842 to 1859. Lyon Levy was state treasurer. A number of Charleston Jews served in the state legislature and as city aldermen. Jews were involved in local benevolent societies and did not seem to suffer any social exclusion.

Jews acted much like other white Charlestonians, including owning slaves. Jewish auctioneers like Abraham Mendes Seixas sold slaves along with other commodities. According to one study, 83% of Jewish households in Charleston owned at least one slave; this figure was slightly lower than the 87% of all white households in the city that owned slaves. Most of the slaves owned by Jews in Charleston were house servants. A handful of successful Jewish merchants in Charleston bought relatively small slave plantations in the western part of the state, but most lived in the port city as was the general practice for South Carolina’s planter elite. Mordecai Cohen owned 27 slaves who worked on his rice plantation. Becoming a slave-owning planter was a way to ascend the social ladder in Charleston, although it often became a significant financial drain for Jews. Although there is little evidence that Jewish slave owners tried to convert their slaves to Judaism, Beth Elohim’s constitution had a provision that banned black converts from membership. Charleston Jews thoroughly accepted the South’s defense of slavery. Jacob Nunez Cardozo was a local newspaper editor who was a staunch supporter of the South’s cause and slavery.

When South Carolina seceded from the Union after the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, Charleston Jews supported the new Confederate States of America. Over 180 Charleston Jews fought for the Confederacy. Successful broker Benjamin Mordecai gave $10,000 to South Carolina to help support the Southern war effort. He also established a charity to help take care of soldiers’ families. Mordecai’s strong support for the Confederate cause eventually cost him; he invested so heavily in Confederate bonds that he was financially ruined by the end of the war.

Although Charleston Jews were bitterly divided over how best to worship God, they were unified on the issue of the country’s growing sectional conflict. Charleston Jews had become well integrated in the city’s economic, political, and social life. Jacob De La Motta, an active leader of Beth Elohim, was a physician who was elected as secretary of the local medical society in 1824. Abraham Moise was a lawyer who served as a local magistrate from 1842 to 1859. Lyon Levy was state treasurer. A number of Charleston Jews served in the state legislature and as city aldermen. Jews were involved in local benevolent societies and did not seem to suffer any social exclusion.

Jews acted much like other white Charlestonians, including owning slaves. Jewish auctioneers like Abraham Mendes Seixas sold slaves along with other commodities. According to one study, 83% of Jewish households in Charleston owned at least one slave; this figure was slightly lower than the 87% of all white households in the city that owned slaves. Most of the slaves owned by Jews in Charleston were house servants. A handful of successful Jewish merchants in Charleston bought relatively small slave plantations in the western part of the state, but most lived in the port city as was the general practice for South Carolina’s planter elite. Mordecai Cohen owned 27 slaves who worked on his rice plantation. Becoming a slave-owning planter was a way to ascend the social ladder in Charleston, although it often became a significant financial drain for Jews. Although there is little evidence that Jewish slave owners tried to convert their slaves to Judaism, Beth Elohim’s constitution had a provision that banned black converts from membership. Charleston Jews thoroughly accepted the South’s defense of slavery. Jacob Nunez Cardozo was a local newspaper editor who was a staunch supporter of the South’s cause and slavery.

When South Carolina seceded from the Union after the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, Charleston Jews supported the new Confederate States of America. Over 180 Charleston Jews fought for the Confederacy. Successful broker Benjamin Mordecai gave $10,000 to South Carolina to help support the Southern war effort. He also established a charity to help take care of soldiers’ families. Mordecai’s strong support for the Confederate cause eventually cost him; he invested so heavily in Confederate bonds that he was financially ruined by the end of the war.

Reconstructing Charleston’s Jewish Community: 1865-1900

Both Beth Elohim and Shearith Israel suffered during the Civil War. Members of Beth Elohim had taken the congregation’s Torah scrolls and organ to the state capital of Columbia in hopes of protecting them from the Union Army. Despite this precaution, these items were destroyed when General Sherman’s troops torched Columbia. During most of the war, the congregation was inactive, and after Appomattox, Beth Elohim’s membership was severely depleted, reaching a low of 11 members at the end of the war. Shearith Israel’s synagogue sustained heavy damage during the war. Both congregations soon saw the benefits of reuniting.

Just as the nation had to come back together after the war, so did the Jewish community of Charleston. Out of necessity rather than any theological agreement, Beth Elohim and Shearith Israel agreed to merge; although Shearith Israel had four times as many members, the resulting congregation took Beth Elohim’s name and used its synagogue, which had not been significantly damaged during the war. Merging an Orthodox and a Reform congregation required tolerance and diplomacy on both sides. They agreed to use the Sephardic Orthodox rite, though the Sabbath service was shortened. The members went through the Saturday morning service and specified exactly which prayers would be included, incorporating both Orthodox and Reform elements. These compromises were noted in the congregation’s board minutes. For example, it specified that the prayer Adon Olam would be sung in Hebrew one week, and in English the following week. While there was to be no organ, they would have a co-ed choir that sang in both English and Hebrew. This merger agreement was designed to last six years. Not surprisingly, not everyone was happy with these compromises, and a handful of members left. The congregation faced hard times as Charleston struggled to get back on its economic feet after the war.

Even before the Civil War, an influx of Jewish immigrants from Poland and the German states began to arrive in Charleston. Most of them started as peddlers before opening retail businesses in town. By 1867, Jews owned almost one-third of the 50 dry goods stores and half of the 20 clothing businesses in the city. Some became rather successful. M. Hornik started Hornik’s Bargain House in 1886 as a small wholesale business. By 1901, it had grown to fill a four-story building and sent out 40,000 catalogs to its mail order customers. For those who struggled, Charleston Jews founded the Russian Emigrant Society to help care for the newcomers.

Both Beth Elohim and Shearith Israel suffered during the Civil War. Members of Beth Elohim had taken the congregation’s Torah scrolls and organ to the state capital of Columbia in hopes of protecting them from the Union Army. Despite this precaution, these items were destroyed when General Sherman’s troops torched Columbia. During most of the war, the congregation was inactive, and after Appomattox, Beth Elohim’s membership was severely depleted, reaching a low of 11 members at the end of the war. Shearith Israel’s synagogue sustained heavy damage during the war. Both congregations soon saw the benefits of reuniting.

Just as the nation had to come back together after the war, so did the Jewish community of Charleston. Out of necessity rather than any theological agreement, Beth Elohim and Shearith Israel agreed to merge; although Shearith Israel had four times as many members, the resulting congregation took Beth Elohim’s name and used its synagogue, which had not been significantly damaged during the war. Merging an Orthodox and a Reform congregation required tolerance and diplomacy on both sides. They agreed to use the Sephardic Orthodox rite, though the Sabbath service was shortened. The members went through the Saturday morning service and specified exactly which prayers would be included, incorporating both Orthodox and Reform elements. These compromises were noted in the congregation’s board minutes. For example, it specified that the prayer Adon Olam would be sung in Hebrew one week, and in English the following week. While there was to be no organ, they would have a co-ed choir that sang in both English and Hebrew. This merger agreement was designed to last six years. Not surprisingly, not everyone was happy with these compromises, and a handful of members left. The congregation faced hard times as Charleston struggled to get back on its economic feet after the war.

Even before the Civil War, an influx of Jewish immigrants from Poland and the German states began to arrive in Charleston. Most of them started as peddlers before opening retail businesses in town. By 1867, Jews owned almost one-third of the 50 dry goods stores and half of the 20 clothing businesses in the city. Some became rather successful. M. Hornik started Hornik’s Bargain House in 1886 as a small wholesale business. By 1901, it had grown to fill a four-story building and sent out 40,000 catalogs to its mail order customers. For those who struggled, Charleston Jews founded the Russian Emigrant Society to help care for the newcomers.

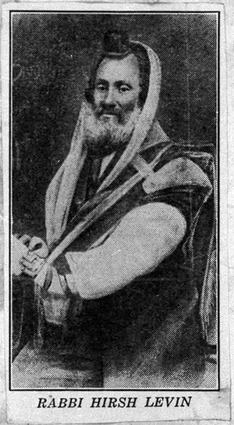

These Polish and German immigrants chose not to join either of the two congregations in Charleston in the 1850s. Beth Elohim’s Reform practice did not match their Orthodox sensibilities while Shearith Israel’s Sephardic ritual was foreign to them. By 1852, a group of immigrants, led by the Lithuanian-born Hirsch Zvi Margolis Levine, had begun to meet together for prayer. By 1854, they had formed congregation B’rith Shalom, which used the traditional Polish rite, and had rented a small wooden building on St. Philip Street. B’rith Shalom met in the building for the next 20 years until they built a permanent synagogue, also on St. Philip Street. The new Orthodox congregation had cordial relations with the Reform Beth Elohim. At the cornerstone laying ceremony for B’rith Shalom’s synagogue, Rabbi Joseph Chumaceiro of Beth Elohim was the featured speaker. Beth Elohim also donated an ark and its old pews to be used in the new shul.

If the members of B’rith Shalom had harmonious interactions with the city’s oldest Jewish congregation, their internal relations were less peaceful. As time went on, some members of B’rith Shalom fell away from strict Orthodox practice in their personal life; some worked on the Sabbath or stopped coming to daily minyans. Those who remained committed to Orthodoxy were unhappy with their fellow members and split off to form their own congregation, Shari Emouna (Gates of Faith), in 1886. Shari Emouna met for daily services in a rented room on King Street, close to where many Charleston Jews had their stores. By 1890, the breakaway congregation had acquired a new Torah. With their most Orthodox members gone, B’rith Shalom began to drift away from strict Orthodox practice, dispensing with the daily minyans and only holding services on Friday nights and Saturday mornings. For reasons lost to history, the two congregations decided to merge in 1897; B’rith Shalom soon reinstated twice daily minyans. Despite the healing of this schism, members’ Orthodox observance would remain a thorny issue at the congregation for the next several decades.

If the members of B’rith Shalom had harmonious interactions with the city’s oldest Jewish congregation, their internal relations were less peaceful. As time went on, some members of B’rith Shalom fell away from strict Orthodox practice in their personal life; some worked on the Sabbath or stopped coming to daily minyans. Those who remained committed to Orthodoxy were unhappy with their fellow members and split off to form their own congregation, Shari Emouna (Gates of Faith), in 1886. Shari Emouna met for daily services in a rented room on King Street, close to where many Charleston Jews had their stores. By 1890, the breakaway congregation had acquired a new Torah. With their most Orthodox members gone, B’rith Shalom began to drift away from strict Orthodox practice, dispensing with the daily minyans and only holding services on Friday nights and Saturday mornings. For reasons lost to history, the two congregations decided to merge in 1897; B’rith Shalom soon reinstated twice daily minyans. Despite the healing of this schism, members’ Orthodox observance would remain a thorny issue at the congregation for the next several decades.

Edwin Warren Moise in Confederate uniform

Edwin Warren Moise in Confederate uniform

While B’rith Shalom still faced internal conflict, Beth Elohim finally embraced Reform Judaism fully. In 1872, the congregation bought an organ and a year later became a founding member of Isaac Mayer Wise’s Union of American Hebrew Congregations. By 1879, the congregation had gotten rid of its shochet and instituted “family pews,” in which men and women could sit together. These changes caused a handful of members to leave Beth Elohim and join B’rith Shalom, but most remained members of the city’s 130 year-old congregation.

Charleston Jews suffered during the Reconstruction period as did most other whites in the city. They were strong supporters of Wade Hampton, whose contested election in 1876 ushered in Democratic Party “redemption” in South Carolina. A few Jewish Confederate veterans fought with Hampton’s “Red Shirts” who terrorized the Republican opposition in the state. Rabbi David Levy of Beth Elohim signed a petition with other ministers of Charleston supporting Hampton against charges made by the Reconstructionist Governor Daniel Chamberlain. Edward Warren Moise of Sumter, scion of an old Charleston Jewish family, was elected adjutant-general on Hampton’s ticket. Charleston’s native-born Jews reacted to the racial politics of Reconstruction in a manner that was little different from other whites in the city.

Charleston Jews suffered during the Reconstruction period as did most other whites in the city. They were strong supporters of Wade Hampton, whose contested election in 1876 ushered in Democratic Party “redemption” in South Carolina. A few Jewish Confederate veterans fought with Hampton’s “Red Shirts” who terrorized the Republican opposition in the state. Rabbi David Levy of Beth Elohim signed a petition with other ministers of Charleston supporting Hampton against charges made by the Reconstructionist Governor Daniel Chamberlain. Edward Warren Moise of Sumter, scion of an old Charleston Jewish family, was elected adjutant-general on Hampton’s ticket. Charleston’s native-born Jews reacted to the racial politics of Reconstruction in a manner that was little different from other whites in the city.

The store of an observant Charleston Jew, 1949

The store of an observant Charleston Jew, 1949

Another Eastern European Wave: 1900-1945

The large wave of Eastern European Jewish immigrants that arrived in the United States in the 1880s eventually reached Charleston. Earlier Jewish immigrants from Poland and Eastern Europe had founded the city’s first Ashkenazic synagogue in 1854. But by the early 20th century, Jews from Poland and the Russian Empire began to settle in Charleston and South Carolina in increasing numbers. Between 1900 and 1920, the Jewish population of the state doubled from 2500 to 5000. Like those who had come in the mid-19th century, these new arrivals started as peddlers and often ended up owning small retail stores along King Street, which continued to be dominated by Jewish merchants in the first half of the 20th century. Followers of Orthodox Judaism, most of these new immigrants kept their stores closed on Saturday. Many of these new merchants catered to the city’s black population; they were more likely to offer black customers credit and to allow them to try on merchandise than were other white merchants.

This immigrant community clustered in the uptown area around St. Philip Street, which became known as Charleston’s Jewish neighborhood, although Jews weren’t a majority of its residents. Here, they could speak Yiddish and keep kosher. These new immigrants were quite different from the deeply rooted native-born Jewish population of Charleston. Not being in the South at the time of the Civil War, these immigrants had little attachment to the Old South or the Confederacy.

Despite these cultural differences, Charleston’s old Jewish community worked to help assimilate these newcomers. Female members of Beth Elohim founded the Happy Workers club in 1889, which among other activities offered sewing classes to young immigrant women. The local chapter of the National Council of Jewish Women, which had been founded in 1906, held Americanization classes for Jewish immigrants. The NCJW did not restrict their efforts to the city’s Jewish population. They pushed for health care programs for students in the city’s public schools, including one that tested the hearing of each student. In 1915, they founded a kindergarten for the city’s poor children.

The large wave of Eastern European Jewish immigrants that arrived in the United States in the 1880s eventually reached Charleston. Earlier Jewish immigrants from Poland and Eastern Europe had founded the city’s first Ashkenazic synagogue in 1854. But by the early 20th century, Jews from Poland and the Russian Empire began to settle in Charleston and South Carolina in increasing numbers. Between 1900 and 1920, the Jewish population of the state doubled from 2500 to 5000. Like those who had come in the mid-19th century, these new arrivals started as peddlers and often ended up owning small retail stores along King Street, which continued to be dominated by Jewish merchants in the first half of the 20th century. Followers of Orthodox Judaism, most of these new immigrants kept their stores closed on Saturday. Many of these new merchants catered to the city’s black population; they were more likely to offer black customers credit and to allow them to try on merchandise than were other white merchants.

This immigrant community clustered in the uptown area around St. Philip Street, which became known as Charleston’s Jewish neighborhood, although Jews weren’t a majority of its residents. Here, they could speak Yiddish and keep kosher. These new immigrants were quite different from the deeply rooted native-born Jewish population of Charleston. Not being in the South at the time of the Civil War, these immigrants had little attachment to the Old South or the Confederacy.

Despite these cultural differences, Charleston’s old Jewish community worked to help assimilate these newcomers. Female members of Beth Elohim founded the Happy Workers club in 1889, which among other activities offered sewing classes to young immigrant women. The local chapter of the National Council of Jewish Women, which had been founded in 1906, held Americanization classes for Jewish immigrants. The NCJW did not restrict their efforts to the city’s Jewish population. They pushed for health care programs for students in the city’s public schools, including one that tested the hearing of each student. In 1915, they founded a kindergarten for the city’s poor children.

B'rith Shalom synagogue ca. 1900

B'rith Shalom synagogue ca. 1900

This increased immigration bolstered Charleston’s Orthodox congregation, B’rith Shalom, although it also led to tensions and eventually a schism. In 1907, the congregation had 60 members and an annual income of $3000. Most of the newly arriving immigrants were strict Orthodox Jews, while some of the older B’rith Shalom members were not Orthodox in their daily lives, although the congregation continued to offer a daily Orthodox minyan. When Joseph Volaski became president of the Orthodox congregation in 1911, some members were upset that he did not strictly observe the Sabbath’s rest. This group, most of whom were recent immigrants, split off to form their own Orthodox congregation, which they named Beth Israel. The new congregation worshiped in a small building three blocks from B’rith Shalom on St. Philip Street. By 1920, Beth Israel had 85 members, and would continue to grow over the next three decades. B’rith Shalom thrived as well, enlarging their synagogue in 1929

Kaluszyner Society banquet, 1948

Kaluszyner Society banquet, 1948

Many of these newly arriving immigrants came from Kaluszyn, a town 30 miles outside of Warsaw. So many of them joined Beth Israel that it was informally known as the “Kaluszyner shul.” According to local legend, the first Kaluszyner to come to Charleston was Eleazer Bernstein, who started a long chain of family and friends coming over to the city. These Polish immigrants formed a close-knit group, and even established the Kalushiner Society, which offered sickness benefits and a free loan program to its members. Founded in 1922, the society also raised money to send back to Kaluszyn to help those in need. The society grew after it began to accept members who were not from Kaluszyn. By 1937, the society had 121 members, holding monthly meetings and an annual banquet. After the Holocaust destroyed the Jewish community in Kaluszyn, the society’s mission drifted, and the group eventually disbanded in 1967.

Zionism attracted a small but dedicated following in Charleston. The city’s first Zionist organization, the B’nei Zion Society, was founded sometime before 1917. Joseph Goldman was the longtime leader of the group, which later became known as the Charleston Zionist District. In 1925, Goldman was appointed to the national executive committee of the Zionist Organization of America. Although meetings were at one time held in Yiddish, Zionism in Charleston was not exclusively an Orthodox immigrant cause. Rabbi Jacob Raisin of Beth Elohim was an ardent supporter, serving as vice president of the local Zionist district and attending the World Zionist Congress in 1932. His wife Jane helped to found a local chapter of Hadassah in 1914. The Raisins’ support for Zionism did not seem to concern the members of Beth Elohim, as Rabbi Raisin served the Reform congregation for almost thirty years. Indeed, when his successor, Rabbi Allan Tarshish, became active in the anti-Zionist American Council for Judaism, some members were upset. Local Zionist organizations, which had been rather small, grew significantly after World War II and the establishment of Israel. The Charleston Zionist District had about 30 members in 1931, but grew to 400 by 1950. Hadassah had 40 members in 1927, and over 400 in 1950.

Zionism attracted a small but dedicated following in Charleston. The city’s first Zionist organization, the B’nei Zion Society, was founded sometime before 1917. Joseph Goldman was the longtime leader of the group, which later became known as the Charleston Zionist District. In 1925, Goldman was appointed to the national executive committee of the Zionist Organization of America. Although meetings were at one time held in Yiddish, Zionism in Charleston was not exclusively an Orthodox immigrant cause. Rabbi Jacob Raisin of Beth Elohim was an ardent supporter, serving as vice president of the local Zionist district and attending the World Zionist Congress in 1932. His wife Jane helped to found a local chapter of Hadassah in 1914. The Raisins’ support for Zionism did not seem to concern the members of Beth Elohim, as Rabbi Raisin served the Reform congregation for almost thirty years. Indeed, when his successor, Rabbi Allan Tarshish, became active in the anti-Zionist American Council for Judaism, some members were upset. Local Zionist organizations, which had been rather small, grew significantly after World War II and the establishment of Israel. The Charleston Zionist District had about 30 members in 1931, but grew to 400 by 1950. Hadassah had 40 members in 1927, and over 400 in 1950.

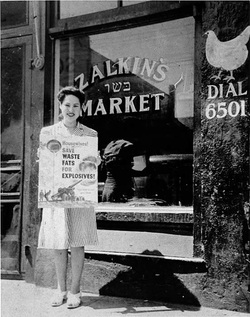

Zalkin's Kosher Meat Market, 1942

Zalkin's Kosher Meat Market, 1942

Charleston Jews Since World War II

World War II had a significant impact on the city of Charleston. After the Civil War, the city had failed to thrive along with the so-called “New South,” as Charleston was unable to keep up with such growing cities as Atlanta and Memphis. World War II ushered in a period of economic growth for Charleston, with increased manufacturing and a revitalized port. A large number of soldiers were stationed in the area during the war, and even more passed through the city. The stores on King Street, still dominated by Jewish merchants, were jumping. With this economic resurgence, the Jewish community of Charleston flourished as well, as its Jewish population more than doubled between 1948 and 1984.

By 1948, over 1900 Jews lived in Charleston, 75% of whom were born in the United States. A number of Jews from New York moved to the city in the years after the war. Jews were still heavily concentrated in business ownership, with 53% of household heads either owning or managing a business. Only 12% were professionals, while 7% were skilled laborers. The most common businesses owned by Jews were clothing, grocery, furniture, and liquor stores. A handful of Jews owned small manufacturing businesses that made such things as undergarments, ties, and mattresses.

Even though open immigration had ended 25 years earlier, Charleston’s Orthodox community remained strong in the early post-war years. In 1948, two kosher butcher shops and several kosher delis still operated in the city. A majority of Charleston Jewish families, 58%, identified as Orthodox in 1948. Beth Israel had 240 members in 1948, when they built a new synagogue on Rutledge Avenue. B’rith Shalom had 280 members, and remained an Orthodox congregation. Its bylaws specifically outlawed organs and mixed-gender seating, while intermarried Jews were not allowed to become members. Despite this persistence of Orthodoxy, the city’s Reform congregation, Beth Elohim remained strong, with 270 member families in 1948.

World War II had a significant impact on the city of Charleston. After the Civil War, the city had failed to thrive along with the so-called “New South,” as Charleston was unable to keep up with such growing cities as Atlanta and Memphis. World War II ushered in a period of economic growth for Charleston, with increased manufacturing and a revitalized port. A large number of soldiers were stationed in the area during the war, and even more passed through the city. The stores on King Street, still dominated by Jewish merchants, were jumping. With this economic resurgence, the Jewish community of Charleston flourished as well, as its Jewish population more than doubled between 1948 and 1984.

By 1948, over 1900 Jews lived in Charleston, 75% of whom were born in the United States. A number of Jews from New York moved to the city in the years after the war. Jews were still heavily concentrated in business ownership, with 53% of household heads either owning or managing a business. Only 12% were professionals, while 7% were skilled laborers. The most common businesses owned by Jews were clothing, grocery, furniture, and liquor stores. A handful of Jews owned small manufacturing businesses that made such things as undergarments, ties, and mattresses.

Even though open immigration had ended 25 years earlier, Charleston’s Orthodox community remained strong in the early post-war years. In 1948, two kosher butcher shops and several kosher delis still operated in the city. A majority of Charleston Jewish families, 58%, identified as Orthodox in 1948. Beth Israel had 240 members in 1948, when they built a new synagogue on Rutledge Avenue. B’rith Shalom had 280 members, and remained an Orthodox congregation. Its bylaws specifically outlawed organs and mixed-gender seating, while intermarried Jews were not allowed to become members. Despite this persistence of Orthodoxy, the city’s Reform congregation, Beth Elohim remained strong, with 270 member families in 1948.

By World War II, some members of B’rith Shalom were pushing for changes in the congregation’s religious practices. In 1943, the congregation hired Solomon Goldfarb, a graduate of Conservative Judaism’s seminary, the Jewish Theological Seminary. Under Goldfarb’s leadership, the congregation drifted toward Conservative Judaism, introducing more English into the liturgy and a Friday night service with mixed seating. After Goldfarb left in 1947, a faction of the congregation pushed to embrace Conservative Judaism fully. At a congregational meeting in 1947, the reformers called for “a new approach to traditional Judaism” while other members called on B’rith Shalom to remain “a fortress of Orthodox Judaism.” The push for reforms failed narrowly in a congregational vote.

After the vote, a group of members, including ten officers and board members, resigned from B’rith Shalom and formed a new conservative congregation, Emanu-El. Despite this rancorous split, a number of Emanu-El members retained their membership at B’rith Shalom. Beth Elohim lent a Torah scroll to Emanu-El, which was the first Conservative congregation in the state. Emanu-El initially worshiped in the Jewish Community Center before purchasing an abandoned army chapel. They later built a synagogue in the suburban northwestern part of the city where many of its members lived.

After the vote, a group of members, including ten officers and board members, resigned from B’rith Shalom and formed a new conservative congregation, Emanu-El. Despite this rancorous split, a number of Emanu-El members retained their membership at B’rith Shalom. Beth Elohim lent a Torah scroll to Emanu-El, which was the first Conservative congregation in the state. Emanu-El initially worshiped in the Jewish Community Center before purchasing an abandoned army chapel. They later built a synagogue in the suburban northwestern part of the city where many of its members lived.

Ceremony marking the merger of the

city's

Ceremony marking the merger of the

city's two Orthodox congregations

This split left B’rith Shalom greatly weakened, and its new rabbi, Gilbert Klaperman, who had been ordained by the Orthodox Yeshiva University, began to call for the reuniting of Charleston’s Orthodox community. There had been more than a little bad blood between the two congregations over the years. In 1930, Beth Israel asked if they could use B’rith Shalom’s shochet, but were turned down. In the late 1930s, the two congregations established the Hebrew Institute, which was designed to teach their children about Judaism. This cooperation was short-lived as both congregations soon pulled their students and established their own separate religious schools. Many in Beth Israel felt that the members of the older, more established B’rith Shalom had looked down on them. But by the late 1940s, their roles had changed. Beth Israel’s members were doing well as their stores flourished in the post-war prosperity. The congregation hired its first full-time rabbi in 1945 and soon after built a new synagogue. In contrast, B’rith Shalom was struggling financially after a sizable minority of its members left to form Emanu-El.

After several years of negotiations, the two Orthodox congregations agreed to merge in 1954. They joined the two names, becoming known as B’rith Shalom Beth Israel, or BSBI informally. They decided to use Beth Israel’s new synagogue on Rutledge Avenue; in a public ceremony, members of B'rith Shalom carried their Torahs to the new home of BSBI. In 1955, the newly reunited congregation hired a new rabbi, Nachum Rabinovitch to lead it. Rabbi Rabinovitch established an Orthodox Jewish day school in 1956; in 1976, its name was changed to the Addlestone Hebrew Academy.

Like Jews around the country, Charleston Jews celebrated their post-war economic success by moving out to the suburbs. Increasingly, Jews left the retail trade of their parents and entered the professional ranks. In Charleston, a prominent Jewish businessman, William Ackerman, helped lead the city into the suburban era, building the first shopping mall and housing subdivision west of the Ashley River. According to historian Dale Rosengarten, “it was said that when Bill Ackerman lifted his rod, the waters of the Ashley parted and the Jews crossed to other side.” As Jews moved to Ackerman’s Windermere subdivision, their institutions crossed the river as well. In 1959, the Jewish Community Center bought land west of the Ashley and completed its new facility there in 1966. Emanu-El also moved west to the suburbs in 1979.

This movement of Charleston’s Jews has raised serious challenges for BSBI, whose synagogue is still located close to downtown Charleston, which is quite far away from its largely suburban membership. A group of these suburban members began to hold a minyan in Windermere in 1964 since they were unable to walk to BSBI’s synagogue. The members of BSBI, seeking to avoid a split, soon embraced the minyan. With this move to the suburbs, many members of BSBI fell away from strict Orthodox practice. By 2004, only 10% of members were “shomer Shabbos,” strictly observing the Sabbath rest. Many members drive to services on Saturday morning. Despite the efforts of Rabbi David Radinsky, who led BSBI from 1970 to 2004, the Orthodox congregation has shrunk and aged. In 2004, the average age of BSBI’s adult members was 70, while less than 20% of the congregation’s households had children under the age of 18.

After several years of negotiations, the two Orthodox congregations agreed to merge in 1954. They joined the two names, becoming known as B’rith Shalom Beth Israel, or BSBI informally. They decided to use Beth Israel’s new synagogue on Rutledge Avenue; in a public ceremony, members of B'rith Shalom carried their Torahs to the new home of BSBI. In 1955, the newly reunited congregation hired a new rabbi, Nachum Rabinovitch to lead it. Rabbi Rabinovitch established an Orthodox Jewish day school in 1956; in 1976, its name was changed to the Addlestone Hebrew Academy.

Like Jews around the country, Charleston Jews celebrated their post-war economic success by moving out to the suburbs. Increasingly, Jews left the retail trade of their parents and entered the professional ranks. In Charleston, a prominent Jewish businessman, William Ackerman, helped lead the city into the suburban era, building the first shopping mall and housing subdivision west of the Ashley River. According to historian Dale Rosengarten, “it was said that when Bill Ackerman lifted his rod, the waters of the Ashley parted and the Jews crossed to other side.” As Jews moved to Ackerman’s Windermere subdivision, their institutions crossed the river as well. In 1959, the Jewish Community Center bought land west of the Ashley and completed its new facility there in 1966. Emanu-El also moved west to the suburbs in 1979.

This movement of Charleston’s Jews has raised serious challenges for BSBI, whose synagogue is still located close to downtown Charleston, which is quite far away from its largely suburban membership. A group of these suburban members began to hold a minyan in Windermere in 1964 since they were unable to walk to BSBI’s synagogue. The members of BSBI, seeking to avoid a split, soon embraced the minyan. With this move to the suburbs, many members of BSBI fell away from strict Orthodox practice. By 2004, only 10% of members were “shomer Shabbos,” strictly observing the Sabbath rest. Many members drive to services on Saturday morning. Despite the efforts of Rabbi David Radinsky, who led BSBI from 1970 to 2004, the Orthodox congregation has shrunk and aged. In 2004, the average age of BSBI’s adult members was 70, while less than 20% of the congregation’s households had children under the age of 18.

The Jewish Community in Charleston Today

BSBI today. Photo by Dale Rosengarten

BSBI today. Photo by Dale Rosengarten

While BSBI has struggled, Charleston’s Jewish community has grown and prospered over the last few decades. Beth Elohim has grown significantly, from 285 families in 1992 to 461 in 2008. Emanu-El had 408 families in 1996, and 436 in 2004. In 2001, an estimated 5,500 Jews lived in Charleston, the largest number ever to live in the city. While most Charleston Jews today have become professionals, a handful remain in the occupation where Jews have flourished for over 250 years: retail trade. Henry Berlinsky opened a clothing store in 1883; his grandson Henry Berlin, still ran Berlin’s Clothing Store in 2005. Henry Berlin’s son and daughters continue to work in their fourth generation family business.

Charleston is a Jewish community that is rightfully proud of its heritage. Jews have lived in Charleston for over 300 years. The city looms large in the history of Reform Judaism in America and boasts one of the oldest synagogues in the country. It has also long been one of the strongest Orthodox communities in the South. While Charleston Jews closely identify with their history, their brightest days may still be ahead of them as Charleston’s Jewish community continues to thrive and grow.

Charleston is a Jewish community that is rightfully proud of its heritage. Jews have lived in Charleston for over 300 years. The city looms large in the history of Reform Judaism in America and boasts one of the oldest synagogues in the country. It has also long been one of the strongest Orthodox communities in the South. While Charleston Jews closely identify with their history, their brightest days may still be ahead of them as Charleston’s Jewish community continues to thrive and grow.