Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Columbia, South Carolina

Overview >> South Carolina >> Columbia

Columbia: Historical Overview

|

Europeans began occupying South Carolina’s backcountry in the 1730s, lured by the colonial government’s offer of 50 acres of land to anyone who would move to the interior. Settlers came from North Carolina and Virginia, as well as from the port city of Charles Town, which was renamed Charleston after the American Revolution. The rolling hills and rivers of the midlands promised newcomers land for farming and water power for milling. Several names that appear in pre-Revolutionary records likely were Jewish, including Jacob Satur, Isaac Jacobs, and Jacob Myers. From colonial times onward, Columbia has been home to a Jewish community.

|

Stories of the Jewish Community in Columbia

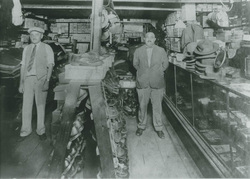

Levy's Dry

Goods Store,

1928.

Levy's Dry

Goods Store,

1928.

Early Settlers

In 1786, when Columbia was designated the state capital, seven Jewish men from Charleston were among the first to invest in town lots. The auction at which they bought the properties was conducted by Joseph Myers, a merchant and member of Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim. In 1790, the first census lists nearly a dozen men with Jewish-sounding surnames, such as Jacobs, Meyers, and Lyons. Centrally located and the seat of state government, the new capital became a bustling crossroads and also the site of South Carolina College, the future University of South Carolina, founded in 1801. The first Jewish students to receive their diplomas were Franklin J. Moses, Sr. (1823), Joseph Lyons (1832), and David Camden DeLeon (1833). The Jewish population of Columbia grew with the general populace; by 1830, an estimated 70 Jews were among its residents.

Most of Columbia’s Jewish pioneers, including 10 of the 11 men who founded the Columbia Hebrew Benevolent Society in 1826, were involved in business and trade. Merchants Judah and Jacob Barrett moved from Charleston to Columbia in the early 1800s. Jacob opened Barrett’s, a dry goods and grocery store, and the brothers engaged in buying and selling land and other speculative business ventures. Judah’s fortunes suffered and, in the 1830s, he left Columbia for New Orleans.

Isaac Lyons, a German immigrant who lived first in Philadelphia and then Charleston, arrived in Columbia in the 1820s. With his grown sons, Henry and Jacob, he established the Lyons Grocery store and operated an oyster saloon, a popular gathering place for South Carolina College students. Also arriving from Charleston in the 1820s, Humphrey and Frances Marks opened the Marks Porter and Relish House.

Levy Pollock and Phineas Solomon partnered in an auction house, competing with fellow auctioneers Jacob and Lipman Levin. Lipman Levin advertised as “auctioneer and commission merchant” for “real estate, stocks and bonds, negroes, cotton, flour, and corn.” The Levins also offered “Dry Goods and Victuals.” Saloon-keeper Isaac D. Mordecai sold wine and liquor, and later, groceries, wholesale and retail. Abraham Lipman made his living as a jeweler and Elias Pollock as a bookkeeper. D. C. Peixotto and Alexander Marks ran clothing stores.

Jews worked in professional occupations as well. Chapman Levy, a Camden native, was admitted to the Columbia bar in 1806. The lawyer was a legislator, soldier, landowner, Mason, proprietor of a brickyard in Columbia, and expert on the practice of dueling. Records reveal he owned 31 slaves in 1820, more than any other Jew in the state. Levy lived in Columbia in the 1820s, but returned to his hometown later that decade and in 1838 resettled in Mississippi. Dr. Mordecai Hendricks DeLeon, a descendant of Sephardic Jews who came to the colonies in the early 1700s, settled in Columbia in the 1820s. He ran an asylum for the mentally ill and a general hospital that admitted black as well as white South Carolinians.

Charlestonian Elias Marks, son of Humphrey and Frances, was a physician who settled in Columbia in the early 19th century. He and his wife, Jane Barham Marks, devoted themselves to the education of women. Jane assisted with school activities at the Columbia Female Academy, where Elias served as principal from 1817 to 1827. They lobbied the legislature for the establishment of a facility for the higher education of women. When their efforts failed, they founded the South Carolina Female Institute in 1828, which Elias headed for three decades. Jane did not live to see opening day of the school she had helped to establish. In her honor, the Institute was popularly referred to as Barhamville Academy. In the 1830s, Elias remarried. Reports that say he converted to Christianity differ as to whether he did so as a child or after his second marriage. His first wife, Jane, was not Jewish.

In 1786, when Columbia was designated the state capital, seven Jewish men from Charleston were among the first to invest in town lots. The auction at which they bought the properties was conducted by Joseph Myers, a merchant and member of Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim. In 1790, the first census lists nearly a dozen men with Jewish-sounding surnames, such as Jacobs, Meyers, and Lyons. Centrally located and the seat of state government, the new capital became a bustling crossroads and also the site of South Carolina College, the future University of South Carolina, founded in 1801. The first Jewish students to receive their diplomas were Franklin J. Moses, Sr. (1823), Joseph Lyons (1832), and David Camden DeLeon (1833). The Jewish population of Columbia grew with the general populace; by 1830, an estimated 70 Jews were among its residents.

Most of Columbia’s Jewish pioneers, including 10 of the 11 men who founded the Columbia Hebrew Benevolent Society in 1826, were involved in business and trade. Merchants Judah and Jacob Barrett moved from Charleston to Columbia in the early 1800s. Jacob opened Barrett’s, a dry goods and grocery store, and the brothers engaged in buying and selling land and other speculative business ventures. Judah’s fortunes suffered and, in the 1830s, he left Columbia for New Orleans.

Isaac Lyons, a German immigrant who lived first in Philadelphia and then Charleston, arrived in Columbia in the 1820s. With his grown sons, Henry and Jacob, he established the Lyons Grocery store and operated an oyster saloon, a popular gathering place for South Carolina College students. Also arriving from Charleston in the 1820s, Humphrey and Frances Marks opened the Marks Porter and Relish House.

Levy Pollock and Phineas Solomon partnered in an auction house, competing with fellow auctioneers Jacob and Lipman Levin. Lipman Levin advertised as “auctioneer and commission merchant” for “real estate, stocks and bonds, negroes, cotton, flour, and corn.” The Levins also offered “Dry Goods and Victuals.” Saloon-keeper Isaac D. Mordecai sold wine and liquor, and later, groceries, wholesale and retail. Abraham Lipman made his living as a jeweler and Elias Pollock as a bookkeeper. D. C. Peixotto and Alexander Marks ran clothing stores.

Jews worked in professional occupations as well. Chapman Levy, a Camden native, was admitted to the Columbia bar in 1806. The lawyer was a legislator, soldier, landowner, Mason, proprietor of a brickyard in Columbia, and expert on the practice of dueling. Records reveal he owned 31 slaves in 1820, more than any other Jew in the state. Levy lived in Columbia in the 1820s, but returned to his hometown later that decade and in 1838 resettled in Mississippi. Dr. Mordecai Hendricks DeLeon, a descendant of Sephardic Jews who came to the colonies in the early 1700s, settled in Columbia in the 1820s. He ran an asylum for the mentally ill and a general hospital that admitted black as well as white South Carolinians.

Charlestonian Elias Marks, son of Humphrey and Frances, was a physician who settled in Columbia in the early 19th century. He and his wife, Jane Barham Marks, devoted themselves to the education of women. Jane assisted with school activities at the Columbia Female Academy, where Elias served as principal from 1817 to 1827. They lobbied the legislature for the establishment of a facility for the higher education of women. When their efforts failed, they founded the South Carolina Female Institute in 1828, which Elias headed for three decades. Jane did not live to see opening day of the school she had helped to establish. In her honor, the Institute was popularly referred to as Barhamville Academy. In the 1830s, Elias remarried. Reports that say he converted to Christianity differ as to whether he did so as a child or after his second marriage. His first wife, Jane, was not Jewish.

Organized Jewish Life in Columbia

In the early 19th century, Columbian Jews began to establish the city’s earliest Jewish institutions. In 1822, members of a growing Jewish community founded the Hebrew Burial Society and established a cemetery. Four years later, 11 men organized the Columbia Hebrew Benevolent Society and assumed control of the cemetery, naming it the Hebrew Benevolent Society Cemetery. The third oldest society of its kind in South Carolina, the Benevolent Society was chartered in 1834 and auctioneer Phineas Solomon served as its first president. In the same period, the women of the community established a Ladies Benevolent Society.

Members of the community had little exposure to formal Jewish observance or education, though families did celebrate the High Holy Days either in their homes or in Charleston, and, according to historians Richard and Belinda Gergel, “without exception” Columbia’s Jewish merchants closed their stores on the Sabbath. By the 1840s, the Jewish population had increased to about 25 families and, with the support of this critical mass, gathering for education and worship became a viable option. In 1843, the Columbia Israelite Sunday School opened under the direction of Boanna Wolff. Originally from Alabama, Wolff was visiting Columbia from her home in Philadelphia, where Rebecca Gratz had started America’s first Jewish Sunday school. Inspired by Gratz’s work and seeing the need to educate Columbia’s Jewish children, Wolff extended her visit long enough to start the program. She and her assistant, Louisa Hart Lyons, depended on Hebrew Benevolent Society members to provide facilities, books, and other supplies. In the spring of 1844, the first class of roughly two dozen students sat for exams.

Hebrew Benevolent Society members contributed money to build a home for the Sunday school and, in 1846, dedicated the Hebrew Benevolent Society building on Assembly Street. That same year, they formed a congregation, Shearith Israel, or Remnant of Israel, which met for services on the upper floor of the Society’s new quarters. Worshipers used the Sephardic minhag, with English immigrant and auctioneer Jacob Levin serving as president for several years. In December 1846, The Occident and American Jewish Advocate reported that the “number of members” in the Columbia congregation “is small.” Nevertheless, the group appears to have been fairly vital in its first years. Rabbi Philip S. Jacobs served the congregation part-time around 1850, and Samuel M. Laskey acted as chazzan and shohet in 1855. There were occasional disagreements within the congregation; one, in 1849, led to the founding of a short-lived second congregation Darech Amet, or Path of Truth.

In the early 19th century, Columbian Jews began to establish the city’s earliest Jewish institutions. In 1822, members of a growing Jewish community founded the Hebrew Burial Society and established a cemetery. Four years later, 11 men organized the Columbia Hebrew Benevolent Society and assumed control of the cemetery, naming it the Hebrew Benevolent Society Cemetery. The third oldest society of its kind in South Carolina, the Benevolent Society was chartered in 1834 and auctioneer Phineas Solomon served as its first president. In the same period, the women of the community established a Ladies Benevolent Society.

Members of the community had little exposure to formal Jewish observance or education, though families did celebrate the High Holy Days either in their homes or in Charleston, and, according to historians Richard and Belinda Gergel, “without exception” Columbia’s Jewish merchants closed their stores on the Sabbath. By the 1840s, the Jewish population had increased to about 25 families and, with the support of this critical mass, gathering for education and worship became a viable option. In 1843, the Columbia Israelite Sunday School opened under the direction of Boanna Wolff. Originally from Alabama, Wolff was visiting Columbia from her home in Philadelphia, where Rebecca Gratz had started America’s first Jewish Sunday school. Inspired by Gratz’s work and seeing the need to educate Columbia’s Jewish children, Wolff extended her visit long enough to start the program. She and her assistant, Louisa Hart Lyons, depended on Hebrew Benevolent Society members to provide facilities, books, and other supplies. In the spring of 1844, the first class of roughly two dozen students sat for exams.

Hebrew Benevolent Society members contributed money to build a home for the Sunday school and, in 1846, dedicated the Hebrew Benevolent Society building on Assembly Street. That same year, they formed a congregation, Shearith Israel, or Remnant of Israel, which met for services on the upper floor of the Society’s new quarters. Worshipers used the Sephardic minhag, with English immigrant and auctioneer Jacob Levin serving as president for several years. In December 1846, The Occident and American Jewish Advocate reported that the “number of members” in the Columbia congregation “is small.” Nevertheless, the group appears to have been fairly vital in its first years. Rabbi Philip S. Jacobs served the congregation part-time around 1850, and Samuel M. Laskey acted as chazzan and shohet in 1855. There were occasional disagreements within the congregation; one, in 1849, led to the founding of a short-lived second congregation Darech Amet, or Path of Truth.

House of Peace's

synagogue later

became the

House of Peace's

synagogue later

became the famous Big Apple Night Club.

Photo by Dale Rosengarten

Civic Engagement in the 19th Century

Columbia’s thriving economy was based primarily on cotton and tobacco crops. When the railroad came to Columbia in 1842, the geographic and political center of South Carolina became a commercial hub as well. Columbia’s Jews, generally well accepted, were active in civic affairs. They served in the Richland Volunteer Rifle Company, joined the Masons, and acted as bank officers. While credit reports reveal threads of discriminatory stereotyping running through the antebellum years, Jews nevertheless achieved prominent positions in local politics. In 1827, Judah Barrett became the first Jew to hold an elected post. He served as warden, or city councilman, for two terms. Mordecai DeLeon held the intendant, or mayoral, post for three terms starting in 1833. Henry Lyons served as warden for eight years and, in 1850, became Columbia’s second Jewish mayor.

The Civil War and After

The Civil War was a time of great turmoil for Columbia, and local Jews rallied to the Southern cause. Boanna Wolff Levy rallied Columbia women in support of the Confederacy. She and Jacob Levin founded the Ladies Industrial Society, which organized sewing jobs. After the war, Boanna joined the Richland Ladies Memorial Association, which tended the graves of Confederate soldiers and erected the Confederate Monument at the State House. Columbia suffered significant destruction when Union forces occupied the city in February 1865. The Hebrew Benevolent Society building was destroyed by fire during the occupation.

In 1866, the Jewish community regrouped and began meeting for services that followed the German minhag. Some of the officers and trustees, such as Jacob Levin, had been members of the former Shearith Israel, but others were new to Columbia. Differences of opinion led to separate High Holy Days services that same year—“one for the Polish and the other for Portuguese,” according to an account in the Occident, but the Society resumed its organizational meetings and upkeep of the cemetery. In 1867, the Sunday school resumed its activities with almost three dozen students under the direction of Boanna Wolff Levy and Mrs. Lipman T. Levy.

While the congregation dissolved over the next two decades, some religious observance continued with the guidance of three lay leaders, Abraham Isaac Trager, Philip Epstin, and Henry Steel. Trager, a Lithuanian, arrived in Columbia before the Civil War. The 1880 census lists him as “minister,” and indeed, besides serving as shochet, he conducted weddings, circumcisions, bar mitzvah ceremonies, and funerals in Columbia and the surrounding towns. Epstin emigrated from Poland to Charleston with his parents in the 1850s. In 1867, he and his brother David opened D. Epstin’s Clothing Store in Columbia. Steele was an Austrian immigrant who had lived in Charleston and Marion, South Carolina, before coming to Columbia to open a store in 1871. His knowledge of Hebrew served him well as lay leader.

The Civil War disrupted religious organizations and took a toll on Jewish businesses. Grocer Jacob Lyons lost everything and left Columbia to start over elsewhere. Other Jews chose to remain in Columbia and reopen their businesses, including Dr. P. Melvin Cohen, a dentist who sold “tea, coffee, sugar, and medicine.” Also part of the rebounding economy were Jacob Cohen, selling salt and candy, grocers Hardy Solomon and Melvin M. Cohen, and E. H. Moïse & Company, general merchandisers.

By the late 1870s, Columbia’s business climate had cooled and, as a result, many Jews left the city, seeking opportunities elsewhere. As the Jewish population declined, the recently formed B’nai B’rith chapter closed and membership in the Hebrew Benevolent Society shrunk to eight, hopes for building a synagogue were dashed, and the Sunday school shut down. Of the nearly two dozen Jewish families that remained, most of whom were involved in business, only three closed their stores on Saturdays. Nevertheless, Columbia’s first bar mitzvah took place in 1878, conducted by lay leader Henry Steele. In the 1880s, in the absence of an organized congregation, Mrs. A. H. Mordecai, Boanna’s daughter, reopened the Sunday school, and Henry Steele, Abraham Isaac Trager, and Philip Epstin led High Holy Days services. The Benevolent Society held monthly meetings at a variety of locations and continued in its role as caretaker of the cemetery. In 1884, members agreed to construct a building to accommodate two stores as rental property on their Assembly Street lot, which had been empty since the war.

Columbia’s thriving economy was based primarily on cotton and tobacco crops. When the railroad came to Columbia in 1842, the geographic and political center of South Carolina became a commercial hub as well. Columbia’s Jews, generally well accepted, were active in civic affairs. They served in the Richland Volunteer Rifle Company, joined the Masons, and acted as bank officers. While credit reports reveal threads of discriminatory stereotyping running through the antebellum years, Jews nevertheless achieved prominent positions in local politics. In 1827, Judah Barrett became the first Jew to hold an elected post. He served as warden, or city councilman, for two terms. Mordecai DeLeon held the intendant, or mayoral, post for three terms starting in 1833. Henry Lyons served as warden for eight years and, in 1850, became Columbia’s second Jewish mayor.

The Civil War and After

The Civil War was a time of great turmoil for Columbia, and local Jews rallied to the Southern cause. Boanna Wolff Levy rallied Columbia women in support of the Confederacy. She and Jacob Levin founded the Ladies Industrial Society, which organized sewing jobs. After the war, Boanna joined the Richland Ladies Memorial Association, which tended the graves of Confederate soldiers and erected the Confederate Monument at the State House. Columbia suffered significant destruction when Union forces occupied the city in February 1865. The Hebrew Benevolent Society building was destroyed by fire during the occupation.

In 1866, the Jewish community regrouped and began meeting for services that followed the German minhag. Some of the officers and trustees, such as Jacob Levin, had been members of the former Shearith Israel, but others were new to Columbia. Differences of opinion led to separate High Holy Days services that same year—“one for the Polish and the other for Portuguese,” according to an account in the Occident, but the Society resumed its organizational meetings and upkeep of the cemetery. In 1867, the Sunday school resumed its activities with almost three dozen students under the direction of Boanna Wolff Levy and Mrs. Lipman T. Levy.

While the congregation dissolved over the next two decades, some religious observance continued with the guidance of three lay leaders, Abraham Isaac Trager, Philip Epstin, and Henry Steel. Trager, a Lithuanian, arrived in Columbia before the Civil War. The 1880 census lists him as “minister,” and indeed, besides serving as shochet, he conducted weddings, circumcisions, bar mitzvah ceremonies, and funerals in Columbia and the surrounding towns. Epstin emigrated from Poland to Charleston with his parents in the 1850s. In 1867, he and his brother David opened D. Epstin’s Clothing Store in Columbia. Steele was an Austrian immigrant who had lived in Charleston and Marion, South Carolina, before coming to Columbia to open a store in 1871. His knowledge of Hebrew served him well as lay leader.

The Civil War disrupted religious organizations and took a toll on Jewish businesses. Grocer Jacob Lyons lost everything and left Columbia to start over elsewhere. Other Jews chose to remain in Columbia and reopen their businesses, including Dr. P. Melvin Cohen, a dentist who sold “tea, coffee, sugar, and medicine.” Also part of the rebounding economy were Jacob Cohen, selling salt and candy, grocers Hardy Solomon and Melvin M. Cohen, and E. H. Moïse & Company, general merchandisers.

By the late 1870s, Columbia’s business climate had cooled and, as a result, many Jews left the city, seeking opportunities elsewhere. As the Jewish population declined, the recently formed B’nai B’rith chapter closed and membership in the Hebrew Benevolent Society shrunk to eight, hopes for building a synagogue were dashed, and the Sunday school shut down. Of the nearly two dozen Jewish families that remained, most of whom were involved in business, only three closed their stores on Saturdays. Nevertheless, Columbia’s first bar mitzvah took place in 1878, conducted by lay leader Henry Steele. In the 1880s, in the absence of an organized congregation, Mrs. A. H. Mordecai, Boanna’s daughter, reopened the Sunday school, and Henry Steele, Abraham Isaac Trager, and Philip Epstin led High Holy Days services. The Benevolent Society held monthly meetings at a variety of locations and continued in its role as caretaker of the cemetery. In 1884, members agreed to construct a building to accommodate two stores as rental property on their Assembly Street lot, which had been empty since the war.

The Turn of the 20th Century

In 1896, 18 Jews organized a new congregation called Tree of Life, with Henry Steele as the first president. Lacking sufficient funds to build a synagogue, members met in homes and at the Assembly Street firehouse, but from the start had their eyes on a Lady Street lot. By 1903, they had raised the $1,000 necessary to buy it. In September 1905, Tree of Life dedicated its new sanctuary. When Tree of Life was founded, members described its religious philosophy as “liberal orthodoxy,” which reflected a divide between Reform-minded members and those who adhered to Orthodox practices as well as cultural differences between Central and Eastern European members. Initially, Orthodox members constituted the majority and services followed their preference. Within a decade of its founding, however, Tree of Life membership grew and those who favored Reform became the new majority, one that dominated the board and utilized its power to align the congregation with the Reform movement. These changes led to acrimony among the congregation’s founders and even a lawsuit. Eventually, these religious disagreements led to an irreparable split, as Orthodox members, led by Phil Epstin, broke away in 1907 to form House of Peace.

Despite this split, some Jewish organizations sought to bring the local Jewish community together. In 1905, Irene Goldsmith Kohn helped to found the Ladies Aid Society, which played a crucial role in the local Jewish community. Society members ran Tree of Life’s religious school, which was open to all Jewish children in the city. The society also hired visiting rabbis to provide leadership and conduct services. Like the Sunday school, the society was open to women from both congregations and attracted a membership larger than Tree of Life’s. In 1915, the organization joined the National Federation of Temple Sisterhoods and changed its name accordingly, and the Sunday school was renamed the religious school. The Columbia section of the National Council of Jewish Women was established in 1919.

Just after the turn of the century, in an apparent effort to distance itself from the congregational conflict at Tree of Life, the Hebrew Benevolent Society resolved that it would not form an alliance with any other societies or religious groups. The Benevolent Society experienced its own internal conflicts, however. In 1925, members debated about whether to permit the interment of non-Jewish family members in the cemetery. While the motion to allow such burials was rejected, President August Kohn declared his intention to grant the right to do so, unless the Society instructed him to do “otherwise.” His vision of a more liberal burial policy was realized in 1934, when the Constitution was revised to accept non-Jewish family members.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Columbia’s Jews, like their predecessors, tended to operate their own businesses and were involved in local organizations and politics. Barnett Berman, a Polish immigrant who moved to Columbia in 1871 as a young man and opened a clothing store on Assembly Street, served as president of the Hebrew Benevolent Society for nearly 30 years and was active as a Mason. Mordecai David, also Polish, came to the capital from Charleston right after the Civil War. A brother-in-law of Philip Epstin, he owned a number of businesses selling clothing and groceries, and served on city council in the early 1900s. His sons Aaron and Levi were founding members of the Tree of Life congregation. Aaron operated two clothing stores in Columbia and Levi became a lawyer and moved to Washington D.C. in the 1890s. Restaurant owner Theodore M. Pollock ran the Wheeler House and the Pollock House, advertising “Fruits, Confectionary and dining saloon.” In the early 1880s, both Pollock and David C. Peixotto, clothing merchant and auctioneer, served on Columbia’s city council.

August Kohn, the son of a German immigrant who settled in Orangeburg before the Civil War, moved to Columbia in 1885 to attend South Carolina College. In 1892, the young journalist was hired as Columbia bureau chief of Charleston’s News and Courier. Although he continued to report on the legislative sessions of the General Assembly, Kohn retired from journalism in 1906. Soon after, he opened August Kohn & Company, a real estate and investment firm. Admired for his integrity and philanthropy, Kohn became a prominent leader in his community and the state. Besides acting as a trustee for the University of South Carolina, he was a Mason and a Shriner, and served as president of Tree of Life and the Hebrew Benevolent Society.

The Early 20th Century

In 1924, Joseph Rubin, a Polish immigrant, moved his family to Columbia from Norway, South Carolina, where he had owned a clothing store. The only Jews in Norway, the Rubins had been treated well by their neighbors, but Joseph’s wife, Bessie Peskin, wanted their children to grow up around other Jews. Rubin established a wholesale dry goods distribution business in Columbia that served merchants throughout the state. J. Rubin and Son stayed open seven days a week to accommodate retailers who came not just to buy merchandise, but to socialize as well. The business thrived as Joseph’s sons, Hyman and Sam, joined the company.

In the 1920s, Frank and Clara Baker moved to Columbia from Estill where Frank had been running his brother’s store. When Frank died at a young age, Clara, a Polish immigrant, operated their grocery and dry goods store by herself until the 1960s, when she sold it to long-time employee, Oscar Shealy. Brothers Philip and Meyer Kline, natives of Lithuania, bought a scrap metal business in Columbia and ultimately established a steel fabrication business. Russian immigrant Myron Bernard Kahn, who had followed his brother to Ohio, settled in Columbia in the late 1920s after business prospects dried up in Ohio and Florida. M. B. was hired by a construction company, later went into business with the owner, and ultimately bought him out. The M. B. Kahn Construction Company built houses initially, then commercial buildings.

Some Columbia Jews played a leading role in the college town’s cultural life. Josiah Morse, Ph.D., born Joseph Moses in 1879 in Richmond, Virginia, was a psychologist and aspiring professor. Unable to find university work because of his Jewish name, he changed it and was hired by the University of Texas before his mentor, the president of the University of South Carolina, invited him to join its faculty in 1911. He was the first Jewish professor to teach at the institution, hired over the protests of some faculty members. Morse spoke out on social justice issues and supported the effort to assist Jewish refugees before and during World War II. Beginning in 1916, he led services at Tree of Life for several years, and in 1936 helped found Columbia B’nai B’rith. When he died in 1946, members honored his memory by renaming the lodge the Josiah Morse Lodge.

Helen Kohn Hennig, daughter of August and Irene Goldsmith Kohn, assumed adult responsibilities in 1913, at age 17, when her mother died. She ran her father’s household, watched over two younger brothers, and stepped into her mother’s leadership position at Tree of Life’s religious school, all the while keeping up with her college studies. Helen married Julian Hennig of Darlington and, as she raised their children, earned a masters degree in history at the University of South Carolina. The only woman appointed to Columbia’s Sesqui-Centennial Commission, as the chair of its History Committee she supervised and edited Columbia: Capital City of South Carolina, 1786–1936. She continued to write books and work with community organizations such as the Red Cross, Community Chest, the Columbia Art Museum, the USO, Town Theater, the Family Service Center, and the South Carolina Federation of Women’s Clubs. Helen also devoted time and energy to the Tree of Life congregation, leaving an indelible impression on its members, particularly the children who attended the Sunday school. She was involved in every facet of synagogue life and served as an officer in the national and state Sisterhood organizations.

With 24 member-families in 1914, Tree of Life hired its first full-time rabbi, Harry Abrams Merfeld. After two years, however, the congregation could not continue to support the position and had to let him go. Professor Josiah Morse led services for several years, followed by August Kohn and Dr. Isadore Schayer. Fears that the synagogue would close when Morse resigned his leadership position led Kohn and Schayer to commit to attending services every Friday. They kept their promise and often found themselves the only ones in the sanctuary. Schayer, served as lay reader for over twenty years, writing a sermon each week. In the 1920s, Tree of Life struggled with declining membership, non-payment of dues, and lack of participation. The newest Jewish arrivals to Columbia were immigrants from Eastern Europe who tended to join House of Peace.

Tree of Life experienced a resurgence of activity in the 1930s under President M. M. Donen, a clothing merchant. In 1933, with free labor provided by one of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs, Tree of Life constructed a building to house the religious school and a community center. By the mid 1930s, with the capital’s Jewish population nearing 700, the congregation’s membership and financial status had improved considerably and nearly 90 students from Columbia and surrounding small towns, such as North and St. Matthews, were enrolled in the religious school. In 1939, one year after joining the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, Tree of Life hired Rabbi Sidney Ballon. Ballon led Hebrew classes and study groups for adults and held a weekly radio program called “The Tree of Life Synagogue on the Air.” Before volunteering for the Army Air Corps in 1940, he conducted Tree of Life’s first bar mitzvah. When lay leader Dr. Schayer also left to join the war effort, Melvin Harris provided leadership until Ballon returned in 1944.

In 1896, 18 Jews organized a new congregation called Tree of Life, with Henry Steele as the first president. Lacking sufficient funds to build a synagogue, members met in homes and at the Assembly Street firehouse, but from the start had their eyes on a Lady Street lot. By 1903, they had raised the $1,000 necessary to buy it. In September 1905, Tree of Life dedicated its new sanctuary. When Tree of Life was founded, members described its religious philosophy as “liberal orthodoxy,” which reflected a divide between Reform-minded members and those who adhered to Orthodox practices as well as cultural differences between Central and Eastern European members. Initially, Orthodox members constituted the majority and services followed their preference. Within a decade of its founding, however, Tree of Life membership grew and those who favored Reform became the new majority, one that dominated the board and utilized its power to align the congregation with the Reform movement. These changes led to acrimony among the congregation’s founders and even a lawsuit. Eventually, these religious disagreements led to an irreparable split, as Orthodox members, led by Phil Epstin, broke away in 1907 to form House of Peace.

Despite this split, some Jewish organizations sought to bring the local Jewish community together. In 1905, Irene Goldsmith Kohn helped to found the Ladies Aid Society, which played a crucial role in the local Jewish community. Society members ran Tree of Life’s religious school, which was open to all Jewish children in the city. The society also hired visiting rabbis to provide leadership and conduct services. Like the Sunday school, the society was open to women from both congregations and attracted a membership larger than Tree of Life’s. In 1915, the organization joined the National Federation of Temple Sisterhoods and changed its name accordingly, and the Sunday school was renamed the religious school. The Columbia section of the National Council of Jewish Women was established in 1919.

Just after the turn of the century, in an apparent effort to distance itself from the congregational conflict at Tree of Life, the Hebrew Benevolent Society resolved that it would not form an alliance with any other societies or religious groups. The Benevolent Society experienced its own internal conflicts, however. In 1925, members debated about whether to permit the interment of non-Jewish family members in the cemetery. While the motion to allow such burials was rejected, President August Kohn declared his intention to grant the right to do so, unless the Society instructed him to do “otherwise.” His vision of a more liberal burial policy was realized in 1934, when the Constitution was revised to accept non-Jewish family members.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Columbia’s Jews, like their predecessors, tended to operate their own businesses and were involved in local organizations and politics. Barnett Berman, a Polish immigrant who moved to Columbia in 1871 as a young man and opened a clothing store on Assembly Street, served as president of the Hebrew Benevolent Society for nearly 30 years and was active as a Mason. Mordecai David, also Polish, came to the capital from Charleston right after the Civil War. A brother-in-law of Philip Epstin, he owned a number of businesses selling clothing and groceries, and served on city council in the early 1900s. His sons Aaron and Levi were founding members of the Tree of Life congregation. Aaron operated two clothing stores in Columbia and Levi became a lawyer and moved to Washington D.C. in the 1890s. Restaurant owner Theodore M. Pollock ran the Wheeler House and the Pollock House, advertising “Fruits, Confectionary and dining saloon.” In the early 1880s, both Pollock and David C. Peixotto, clothing merchant and auctioneer, served on Columbia’s city council.

August Kohn, the son of a German immigrant who settled in Orangeburg before the Civil War, moved to Columbia in 1885 to attend South Carolina College. In 1892, the young journalist was hired as Columbia bureau chief of Charleston’s News and Courier. Although he continued to report on the legislative sessions of the General Assembly, Kohn retired from journalism in 1906. Soon after, he opened August Kohn & Company, a real estate and investment firm. Admired for his integrity and philanthropy, Kohn became a prominent leader in his community and the state. Besides acting as a trustee for the University of South Carolina, he was a Mason and a Shriner, and served as president of Tree of Life and the Hebrew Benevolent Society.

The Early 20th Century

In 1924, Joseph Rubin, a Polish immigrant, moved his family to Columbia from Norway, South Carolina, where he had owned a clothing store. The only Jews in Norway, the Rubins had been treated well by their neighbors, but Joseph’s wife, Bessie Peskin, wanted their children to grow up around other Jews. Rubin established a wholesale dry goods distribution business in Columbia that served merchants throughout the state. J. Rubin and Son stayed open seven days a week to accommodate retailers who came not just to buy merchandise, but to socialize as well. The business thrived as Joseph’s sons, Hyman and Sam, joined the company.

In the 1920s, Frank and Clara Baker moved to Columbia from Estill where Frank had been running his brother’s store. When Frank died at a young age, Clara, a Polish immigrant, operated their grocery and dry goods store by herself until the 1960s, when she sold it to long-time employee, Oscar Shealy. Brothers Philip and Meyer Kline, natives of Lithuania, bought a scrap metal business in Columbia and ultimately established a steel fabrication business. Russian immigrant Myron Bernard Kahn, who had followed his brother to Ohio, settled in Columbia in the late 1920s after business prospects dried up in Ohio and Florida. M. B. was hired by a construction company, later went into business with the owner, and ultimately bought him out. The M. B. Kahn Construction Company built houses initially, then commercial buildings.

Some Columbia Jews played a leading role in the college town’s cultural life. Josiah Morse, Ph.D., born Joseph Moses in 1879 in Richmond, Virginia, was a psychologist and aspiring professor. Unable to find university work because of his Jewish name, he changed it and was hired by the University of Texas before his mentor, the president of the University of South Carolina, invited him to join its faculty in 1911. He was the first Jewish professor to teach at the institution, hired over the protests of some faculty members. Morse spoke out on social justice issues and supported the effort to assist Jewish refugees before and during World War II. Beginning in 1916, he led services at Tree of Life for several years, and in 1936 helped found Columbia B’nai B’rith. When he died in 1946, members honored his memory by renaming the lodge the Josiah Morse Lodge.

Helen Kohn Hennig, daughter of August and Irene Goldsmith Kohn, assumed adult responsibilities in 1913, at age 17, when her mother died. She ran her father’s household, watched over two younger brothers, and stepped into her mother’s leadership position at Tree of Life’s religious school, all the while keeping up with her college studies. Helen married Julian Hennig of Darlington and, as she raised their children, earned a masters degree in history at the University of South Carolina. The only woman appointed to Columbia’s Sesqui-Centennial Commission, as the chair of its History Committee she supervised and edited Columbia: Capital City of South Carolina, 1786–1936. She continued to write books and work with community organizations such as the Red Cross, Community Chest, the Columbia Art Museum, the USO, Town Theater, the Family Service Center, and the South Carolina Federation of Women’s Clubs. Helen also devoted time and energy to the Tree of Life congregation, leaving an indelible impression on its members, particularly the children who attended the Sunday school. She was involved in every facet of synagogue life and served as an officer in the national and state Sisterhood organizations.

With 24 member-families in 1914, Tree of Life hired its first full-time rabbi, Harry Abrams Merfeld. After two years, however, the congregation could not continue to support the position and had to let him go. Professor Josiah Morse led services for several years, followed by August Kohn and Dr. Isadore Schayer. Fears that the synagogue would close when Morse resigned his leadership position led Kohn and Schayer to commit to attending services every Friday. They kept their promise and often found themselves the only ones in the sanctuary. Schayer, served as lay reader for over twenty years, writing a sermon each week. In the 1920s, Tree of Life struggled with declining membership, non-payment of dues, and lack of participation. The newest Jewish arrivals to Columbia were immigrants from Eastern Europe who tended to join House of Peace.

Tree of Life experienced a resurgence of activity in the 1930s under President M. M. Donen, a clothing merchant. In 1933, with free labor provided by one of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs, Tree of Life constructed a building to house the religious school and a community center. By the mid 1930s, with the capital’s Jewish population nearing 700, the congregation’s membership and financial status had improved considerably and nearly 90 students from Columbia and surrounding small towns, such as North and St. Matthews, were enrolled in the religious school. In 1939, one year after joining the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, Tree of Life hired Rabbi Sidney Ballon. Ballon led Hebrew classes and study groups for adults and held a weekly radio program called “The Tree of Life Synagogue on the Air.” Before volunteering for the Army Air Corps in 1940, he conducted Tree of Life’s first bar mitzvah. When lay leader Dr. Schayer also left to join the war effort, Melvin Harris provided leadership until Ballon returned in 1944.

Lourie's Store

Photo by

Bill Aron.

Lourie's Store

Photo by

Bill Aron.

After World War II

Tree of Life experienced a growth spurt in the post-war years, signing on 30 new member-families, for a total of 80, and outgrowing the Lady Street synagogue. In 1951 the congregation broke ground in the suburbs, where many members had relocated, and the next spring moved into a new building on Heyward Street, complete with kitchen, social hall, seven classrooms, and an office for the rabbi. Four years later, a wing was added to the religious school and construction of a Jewish Community Center had begun. By the early 1960s, Columbia’s Jewish population exceeded 1,200 and Tree of Life’s membership plateaued at just over 100. Recruiting efforts paid off in 1969 with an increase in membership of almost one third, requiring renovations in the sanctuary to add seats.

Rabbi Michael Oppenheimer led Tree of Life from 1971 to 1976. Following the path cut earlier by Rabbi David Gruber, Oppenheimer added more Hebrew to services and initiated the bat mitzvah for girls, traditional practices typical of the Reform movement of the 1960s. Oppenheimer joined the Columbia Ministers’ Association and, in 1973, was elected its first Jewish president. He spoke out against racial discrimination and anti-Semitism and stood alongside Jewish politicians such as Hyman Rubin and Isadore Lourie in boycotting meetings held at private facilities that denied admittance to Jews. During Oppenheimer’s tenure, Tree of Life’s membership grew from 132 families to 173, reflecting an increase in Columbia’s Jewish population to 2,300 by 1980. By 1986, membership had grown dramatically to 250 families.

With the surge in membership, the synagogue and religious school were bursting at the seams. Over the objections of some members who wished to remain on Heyward Street, the congregation voted in the spring of 1985 to relocate and rebuild. Although construction was delayed by financial limitations, Tree of Life moved into its new facilities in August 1986. The sanctuary accommodated 360 worshipers and could be expanded to include 500 additional participants with sliding panels pushed back. The property boasted a kitchen, ten classrooms, a chapel, and a sizable library. The Reyner family donated a stained glass window featuring the Star of David, which had been rescued from the House of Peace’s second building.

The newly hired rabbi, Sanford Marcus, arrived in time for the Torah Walk. Four Torahs, one of which had been smuggled out of Germany and donated to Tree of Life by World War II refugees, Gus and Lina Oppenheimer, were carried from the old synagogue to the new. With a police escort, help from members of local churches, and four Fort Jackson Jewish soldiers to carry the chuppah, more than 100 Tree of Life congregants completed the seven-mile walk. Also assisting were members of House of Peace, whose new sanctuary was just a few blocks away.

Despite its rancorous beginning, House of Peace soon grew into a strong and stable congregation. Much of this growth took place under the leadership of David Karesh, who came to Columbia in 1908 to lead the congregation, though he was not an ordained rabbi. For decades, he was the sole shochet in the capital city, providing kosher meat and chicken through Archie Dent’s butcher shop on Assembly Street. Besides serving as rabbi, cantor, shochet, and Hebrew teacher for House of Peace, Karesh also provided his services to Jews living in small towns in the vicinity of Columbia. He performed wedding and bris ceremonies and was a regular visitor at the Levenson home in Bishopville, arriving every two weeks to slaughter chickens for the last family in town keeping kosher. Karesh’s travels placed him in a unique position to become acquainted with Jews across the midlands. A matchmaker of sorts, he personally introduced unattached men and women, some of whom later married.

In 1912, Karesh’s parishioners were worshiping in their own synagogue on Park Street. Consumed by fire three years later, the building was replaced on the same site by a larger structure designed in the traditional style, with a bimah in the center of the sanctuary. After the congregation sold the building in 1936, it became home, for a short time, to The Big Apple Night Club, birthplace of a dance craze by the same name. Members of House of Peace were mortified by the transformation of the old synagogue into a neon-adorned nightclub, but the new dance drew Columbia and the nightclub into the national spotlight. In the mid-1990s, the building was restored and relocated by the Historic Columbia Foundation.

As the Orthodox congregation swelled, female members were able to form their own Ladies Aid Society for Orthodox Women in 1917. Soon thereafter, the group changed its name to the Daughters of Israel. One of the Daughters’ primary objectives was to establish a Sunday school, but their efforts were stymied for years by the lack of a “suitable teacher.” The women, however, did pledge funds for a new synagogue as early as 1925 and continued the drive toward their goal in the 1930s, despite the effects of the Great Depression. The congregation purchased land on Marion Street and member M. B. Kahn built the new house of worship. By the time of the 1935 dedication, membership had doubled to about 70 families. The sanctuary provided seating for up to 425 people with a basement for meetings and classes. Members of the Daughters of Israel insisted that women be allowed to sit downstairs, rather than in the balcony as they had on Park Street. The board agreed to set apart a women’s section on the right side of the sanctuary, and at Rabbi Karesh’s request, removed the first two rows of pews to put distance between the women and the ark. Reportedly, some women continued to sit in the balcony. House of Peace children relied on Tree of Life’s Sunday school until 1946, when the Daughters of Israel and the Akiba Club raised the funds necessary to open their own school.

In 1954, with about 150 member families, House of Peace hired Rabbi Marcus Wald. Soon after his arrival, Karesh’s credentials and role in the congregation came into question. Wald suggested that Karesh be named Rabbi Emeritus. The board agreed, and Karesh continued to serve as a shochet for the community while members of the congregation continued to look to him for spiritual guidance. Rabbi Wald, who died suddenly in 1957, promoted Conservative Judaism, which was appealing to the younger members of the congregation. In 1955, House of Peace discontinued its association with the Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of America, and the following year joined the Conservative United Synagogues of America.

By 1954, the Sunday school, with 100 students enrolled, had outgrown the Marion Street synagogue’s facilities. Congregation president M. B. Kahn envisioned a suburban complex on Trenholm Road large enough to accommodate a Jewish Community Center, an education building, and a new synagogue. His dream of a community center in this location was realized in 1955. The education building was built by M. B. Kahn Construction near the community center on Trenholm Road in the late 1950s. The structure’s 12 classrooms and meeting hall were designed for a growing community. In just four years, Sunday school enrollment had increased to 155, while the Hebrew school hosted 25 students. Inspired by the wave of Jewish nationalism that followed Israel’s Six-Day War, the congregation began using its Hebrew name, Beth Shalom, instead of House of Peace.

During the 1970s, Beth Shalom’s membership dramatically increased with new arrivals as well as returning natives. After delaying for years, the congregation followed the bulk of its members to the suburbs and moved into a new synagogue on Trenholm Road near the community center and the education building. Built by Irwin Kahn, M.B.’s son, and dedicated in 1973, it included a social hall, chapel, and library. Seven years later, a new education building was built adjoining the sanctuary.

While some descendants of East European immigrants adhered to the Old World Orthodoxy of their forebears, in general there was a loosening of traditional practices among the second and third generations both at home and at Beth Shalom. This was especially true in regard to the role of women in the congregation. In the 1950s, women began attending board meetings and, in 1967, they became eligible for nomination to elected positions. Some time after the move to Trenholm Road, men and women began sitting together during services, a change that apparently occurred gradually and without an official edict. While this move drew protests from the Orthodox members, allowing women on the bimah provoked a much stronger response. Despite the protests of a few, a 1983 vote by the congregation assured female members the “same rights as men to participate in all ritual practices.” This vote prompted a group of Orthodox members to meet separately, though they soon returned to the fold.

Jewish Businesses in the 20th Century

In 1937, the city’s Jewish population was estimated at 680 and stores owned by Jewish merchants lined Assembly and Main Streets on the blocks near the House of Peace synagogue. Columbia’s general population swelled in the 1940s with the reactivation of Fort Jackson, known as Camp Jackson during World War I, and the establishment of the Columbia Army Air Base. By 1950, Columbia had surpassed Charleston in its population count, and by 1960, the capital city was home to more than 100,000 people, with non-natives outnumbering native South Carolinians. This influx of transplants was prompted by the city's industrial growth as companies were attracted by Columbia ’s central location, low power rates, and the state’s non-union status. The city’s medical facilities and academic institutions provided further appeal.

Jews were among the local business owners who profited from the influx of new residents and industry. By 1961, the Jewish population had nearly doubled and a variety of Jewish businessmen, besides merchants, advertised their services in Columbia. Holocaust survivor, Ben Stern, was a contractor who could build “a home of distinction.” Sam Bloom owned Shimmy’s Restaurant, where “You haven’t tasted steak until you try our famous Shimmy’s Hickory Smoked Charcoal Broiled Steaks, Specializing in Kosher Style Food.” Manufacturers included Kline Iron & Steel, Sammie Nussbaum’s Public Oil Company, Max Dickman and Oscar Seidenberg’s Columbia Steel & Metal, and Southern Plastics Company, run by J. W. Lindau, III, Leonard Bogen, and Irwin Kahn.

Although many descendants of immigrants aspired to professional careers, the merchant tradition continued well into the second half of the 20th century, with numerous stores run by members of the second generation. Samuel and Hyman Rubin took over J. Rubin and Son from their father, and the wholesale company remained in business until the early 1990s. Barnett Berry’s sons, Nathan, Joe, and Paul, joined him in his department store, which had grown from a small dry goods business. The Rivkin family operated a grocery store and a non-kosher deli. Reportedly, Senator Strom Thurmond was a regular customer at Rivkin’s. Lourie’s, “Columbia’s Leading Fashion Store for Men and Women,” opened in 1948, a branch of the family’s St. George store. The owners, Sol and Mick, were sons of Russian immigrant Louis Lourie, who had followed a cousin south and opened a number of stores in South Carolina and Georgia. The brothers’ success enabled them to expand their business and open new locations throughout Columbia. Lourie’s downtown store, managed by Sol and Mick’s children, was in operation until 2008, when they finally closed their doors for the last time.

Tree of Life experienced a growth spurt in the post-war years, signing on 30 new member-families, for a total of 80, and outgrowing the Lady Street synagogue. In 1951 the congregation broke ground in the suburbs, where many members had relocated, and the next spring moved into a new building on Heyward Street, complete with kitchen, social hall, seven classrooms, and an office for the rabbi. Four years later, a wing was added to the religious school and construction of a Jewish Community Center had begun. By the early 1960s, Columbia’s Jewish population exceeded 1,200 and Tree of Life’s membership plateaued at just over 100. Recruiting efforts paid off in 1969 with an increase in membership of almost one third, requiring renovations in the sanctuary to add seats.

Rabbi Michael Oppenheimer led Tree of Life from 1971 to 1976. Following the path cut earlier by Rabbi David Gruber, Oppenheimer added more Hebrew to services and initiated the bat mitzvah for girls, traditional practices typical of the Reform movement of the 1960s. Oppenheimer joined the Columbia Ministers’ Association and, in 1973, was elected its first Jewish president. He spoke out against racial discrimination and anti-Semitism and stood alongside Jewish politicians such as Hyman Rubin and Isadore Lourie in boycotting meetings held at private facilities that denied admittance to Jews. During Oppenheimer’s tenure, Tree of Life’s membership grew from 132 families to 173, reflecting an increase in Columbia’s Jewish population to 2,300 by 1980. By 1986, membership had grown dramatically to 250 families.

With the surge in membership, the synagogue and religious school were bursting at the seams. Over the objections of some members who wished to remain on Heyward Street, the congregation voted in the spring of 1985 to relocate and rebuild. Although construction was delayed by financial limitations, Tree of Life moved into its new facilities in August 1986. The sanctuary accommodated 360 worshipers and could be expanded to include 500 additional participants with sliding panels pushed back. The property boasted a kitchen, ten classrooms, a chapel, and a sizable library. The Reyner family donated a stained glass window featuring the Star of David, which had been rescued from the House of Peace’s second building.

The newly hired rabbi, Sanford Marcus, arrived in time for the Torah Walk. Four Torahs, one of which had been smuggled out of Germany and donated to Tree of Life by World War II refugees, Gus and Lina Oppenheimer, were carried from the old synagogue to the new. With a police escort, help from members of local churches, and four Fort Jackson Jewish soldiers to carry the chuppah, more than 100 Tree of Life congregants completed the seven-mile walk. Also assisting were members of House of Peace, whose new sanctuary was just a few blocks away.

Despite its rancorous beginning, House of Peace soon grew into a strong and stable congregation. Much of this growth took place under the leadership of David Karesh, who came to Columbia in 1908 to lead the congregation, though he was not an ordained rabbi. For decades, he was the sole shochet in the capital city, providing kosher meat and chicken through Archie Dent’s butcher shop on Assembly Street. Besides serving as rabbi, cantor, shochet, and Hebrew teacher for House of Peace, Karesh also provided his services to Jews living in small towns in the vicinity of Columbia. He performed wedding and bris ceremonies and was a regular visitor at the Levenson home in Bishopville, arriving every two weeks to slaughter chickens for the last family in town keeping kosher. Karesh’s travels placed him in a unique position to become acquainted with Jews across the midlands. A matchmaker of sorts, he personally introduced unattached men and women, some of whom later married.

In 1912, Karesh’s parishioners were worshiping in their own synagogue on Park Street. Consumed by fire three years later, the building was replaced on the same site by a larger structure designed in the traditional style, with a bimah in the center of the sanctuary. After the congregation sold the building in 1936, it became home, for a short time, to The Big Apple Night Club, birthplace of a dance craze by the same name. Members of House of Peace were mortified by the transformation of the old synagogue into a neon-adorned nightclub, but the new dance drew Columbia and the nightclub into the national spotlight. In the mid-1990s, the building was restored and relocated by the Historic Columbia Foundation.

As the Orthodox congregation swelled, female members were able to form their own Ladies Aid Society for Orthodox Women in 1917. Soon thereafter, the group changed its name to the Daughters of Israel. One of the Daughters’ primary objectives was to establish a Sunday school, but their efforts were stymied for years by the lack of a “suitable teacher.” The women, however, did pledge funds for a new synagogue as early as 1925 and continued the drive toward their goal in the 1930s, despite the effects of the Great Depression. The congregation purchased land on Marion Street and member M. B. Kahn built the new house of worship. By the time of the 1935 dedication, membership had doubled to about 70 families. The sanctuary provided seating for up to 425 people with a basement for meetings and classes. Members of the Daughters of Israel insisted that women be allowed to sit downstairs, rather than in the balcony as they had on Park Street. The board agreed to set apart a women’s section on the right side of the sanctuary, and at Rabbi Karesh’s request, removed the first two rows of pews to put distance between the women and the ark. Reportedly, some women continued to sit in the balcony. House of Peace children relied on Tree of Life’s Sunday school until 1946, when the Daughters of Israel and the Akiba Club raised the funds necessary to open their own school.

In 1954, with about 150 member families, House of Peace hired Rabbi Marcus Wald. Soon after his arrival, Karesh’s credentials and role in the congregation came into question. Wald suggested that Karesh be named Rabbi Emeritus. The board agreed, and Karesh continued to serve as a shochet for the community while members of the congregation continued to look to him for spiritual guidance. Rabbi Wald, who died suddenly in 1957, promoted Conservative Judaism, which was appealing to the younger members of the congregation. In 1955, House of Peace discontinued its association with the Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of America, and the following year joined the Conservative United Synagogues of America.

By 1954, the Sunday school, with 100 students enrolled, had outgrown the Marion Street synagogue’s facilities. Congregation president M. B. Kahn envisioned a suburban complex on Trenholm Road large enough to accommodate a Jewish Community Center, an education building, and a new synagogue. His dream of a community center in this location was realized in 1955. The education building was built by M. B. Kahn Construction near the community center on Trenholm Road in the late 1950s. The structure’s 12 classrooms and meeting hall were designed for a growing community. In just four years, Sunday school enrollment had increased to 155, while the Hebrew school hosted 25 students. Inspired by the wave of Jewish nationalism that followed Israel’s Six-Day War, the congregation began using its Hebrew name, Beth Shalom, instead of House of Peace.

During the 1970s, Beth Shalom’s membership dramatically increased with new arrivals as well as returning natives. After delaying for years, the congregation followed the bulk of its members to the suburbs and moved into a new synagogue on Trenholm Road near the community center and the education building. Built by Irwin Kahn, M.B.’s son, and dedicated in 1973, it included a social hall, chapel, and library. Seven years later, a new education building was built adjoining the sanctuary.

While some descendants of East European immigrants adhered to the Old World Orthodoxy of their forebears, in general there was a loosening of traditional practices among the second and third generations both at home and at Beth Shalom. This was especially true in regard to the role of women in the congregation. In the 1950s, women began attending board meetings and, in 1967, they became eligible for nomination to elected positions. Some time after the move to Trenholm Road, men and women began sitting together during services, a change that apparently occurred gradually and without an official edict. While this move drew protests from the Orthodox members, allowing women on the bimah provoked a much stronger response. Despite the protests of a few, a 1983 vote by the congregation assured female members the “same rights as men to participate in all ritual practices.” This vote prompted a group of Orthodox members to meet separately, though they soon returned to the fold.

Jewish Businesses in the 20th Century

In 1937, the city’s Jewish population was estimated at 680 and stores owned by Jewish merchants lined Assembly and Main Streets on the blocks near the House of Peace synagogue. Columbia’s general population swelled in the 1940s with the reactivation of Fort Jackson, known as Camp Jackson during World War I, and the establishment of the Columbia Army Air Base. By 1950, Columbia had surpassed Charleston in its population count, and by 1960, the capital city was home to more than 100,000 people, with non-natives outnumbering native South Carolinians. This influx of transplants was prompted by the city's industrial growth as companies were attracted by Columbia ’s central location, low power rates, and the state’s non-union status. The city’s medical facilities and academic institutions provided further appeal.

Jews were among the local business owners who profited from the influx of new residents and industry. By 1961, the Jewish population had nearly doubled and a variety of Jewish businessmen, besides merchants, advertised their services in Columbia. Holocaust survivor, Ben Stern, was a contractor who could build “a home of distinction.” Sam Bloom owned Shimmy’s Restaurant, where “You haven’t tasted steak until you try our famous Shimmy’s Hickory Smoked Charcoal Broiled Steaks, Specializing in Kosher Style Food.” Manufacturers included Kline Iron & Steel, Sammie Nussbaum’s Public Oil Company, Max Dickman and Oscar Seidenberg’s Columbia Steel & Metal, and Southern Plastics Company, run by J. W. Lindau, III, Leonard Bogen, and Irwin Kahn.

Although many descendants of immigrants aspired to professional careers, the merchant tradition continued well into the second half of the 20th century, with numerous stores run by members of the second generation. Samuel and Hyman Rubin took over J. Rubin and Son from their father, and the wholesale company remained in business until the early 1990s. Barnett Berry’s sons, Nathan, Joe, and Paul, joined him in his department store, which had grown from a small dry goods business. The Rivkin family operated a grocery store and a non-kosher deli. Reportedly, Senator Strom Thurmond was a regular customer at Rivkin’s. Lourie’s, “Columbia’s Leading Fashion Store for Men and Women,” opened in 1948, a branch of the family’s St. George store. The owners, Sol and Mick, were sons of Russian immigrant Louis Lourie, who had followed a cousin south and opened a number of stores in South Carolina and Georgia. The brothers’ success enabled them to expand their business and open new locations throughout Columbia. Lourie’s downtown store, managed by Sol and Mick’s children, was in operation until 2008, when they finally closed their doors for the last time.

Jewish elected

officials in front

of

Jewish elected

officials in front

of South Carolina's capitol.

Photo by Bill Aron.

Civic Engagement

The Lourie family also made their mark in politics. Isadore, Louis’s youngest son, graduated from the law school at the University of South Carolina in 1956 and was practicing law in Columbia when he was elected to the South Carolina House of Representatives in 1964. He served in the state Senate from 1972 until he retired in 1993. He considered himself a “staunch Democrat” and fought for causes that benefited the average citizen. In 1994, he founded the Jewish Historical Society of South Carolina, an organization dedicated to preserving and documenting South Carolina’s Jewish history. Isadore’s son, Joel, is following in his father’s footsteps. He served in the state House of Representatives from 1999 to 2004, then became a state senator.

Other Columbia Jews were active in civic and political affairs. Hyman Rubin had a long and distinguished career in local and state politics. He served on Columbia City Council from 1952 to 1966 and in the state Senate from 1967 to 1984. A champion of social justice, particularly racial integration, he founded the Columbia Luncheon Club, a forum for blacks and whites to discuss issues of concern. Hyman also sat on the boards of the Chamber of Commerce, the Republic National Bank, Community Chest, and the South Carolina Federation of the Blind. In 1997, he was presented with the Distinguished Service Award from the Greater Columbia Community Relations Council.

During the 20th century, a number of South Carolina Jews called Columbia home for the months when the legislature was in session. Sylvia Dreyfus of Greenville, Irene Krugman Rudnick of Aiken, Harriet Keyserling and her son William Keyserling of Beaufort, and Leonard Krawcheck of Charleston all served in the House of Representatives. Arnold Goodstein, also of Charleston, served in both the House and the Senate and Sol Blatt of Blackville was the Speaker of the House for more than three decades.

The Lourie family also made their mark in politics. Isadore, Louis’s youngest son, graduated from the law school at the University of South Carolina in 1956 and was practicing law in Columbia when he was elected to the South Carolina House of Representatives in 1964. He served in the state Senate from 1972 until he retired in 1993. He considered himself a “staunch Democrat” and fought for causes that benefited the average citizen. In 1994, he founded the Jewish Historical Society of South Carolina, an organization dedicated to preserving and documenting South Carolina’s Jewish history. Isadore’s son, Joel, is following in his father’s footsteps. He served in the state House of Representatives from 1999 to 2004, then became a state senator.

Other Columbia Jews were active in civic and political affairs. Hyman Rubin had a long and distinguished career in local and state politics. He served on Columbia City Council from 1952 to 1966 and in the state Senate from 1967 to 1984. A champion of social justice, particularly racial integration, he founded the Columbia Luncheon Club, a forum for blacks and whites to discuss issues of concern. Hyman also sat on the boards of the Chamber of Commerce, the Republic National Bank, Community Chest, and the South Carolina Federation of the Blind. In 1997, he was presented with the Distinguished Service Award from the Greater Columbia Community Relations Council.

During the 20th century, a number of South Carolina Jews called Columbia home for the months when the legislature was in session. Sylvia Dreyfus of Greenville, Irene Krugman Rudnick of Aiken, Harriet Keyserling and her son William Keyserling of Beaufort, and Leonard Krawcheck of Charleston all served in the House of Representatives. Arnold Goodstein, also of Charleston, served in both the House and the Senate and Sol Blatt of Blackville was the Speaker of the House for more than three decades.

The Jewish Community in Columbia Today

In recent years, Columbia’s Jewish community and institutions have continued to thrive. According to population estimates, more Jews lived in Columbia in 2001, 2,750, than ever lived there before. Under the stewardship of Rabbi Philip Silverstein, who served the congregation for 15 years, Beth Shalom continued to grow and make changes. Members elected their first female president, Carol Bernstein, added a new educational wing, established a new Beth Shalom Cemetery on Arcadia Lakes Drive to succeed the 100 year-old Whaley Street Cemetery which was almost full, and built a community mikvah, the first available since the days of the Park Street synagogue.

Beth Shalom also hosts the Jewish Day School, which is run by Chabad of Columbia. Organized in 1987 by Rabbi Hesh Epstein, Chabad initially held minyanim in Epstein’s living room. Today the Orthodox group is a vibrant congregation with its own home, the Chabad/Aleph House, as well as a team of spiritual leaders. The elementary day school, which opened in 1992 with 12 students, had 205 students in 2008.

In 2005, the Katie and Irwin Kahn Jewish Community Center was completed, replacing the decades-old facility built by Irwin’s father. Construction of the modern facility was made possible by the cooperative efforts of the members of Tree of Life and Beth Shalom, many of whom hold membership in both synagogues. The Community Center is located on the Gerry Sue and Norman Arnold Community Campus, also home to the Columbia Jewish Federation, the philanthropic arm of the Columbia Jewish community. Despite its relatively small size, Columbia’s Jewish community continues to grow and offer significant Jewish resources to its members.

Beth Shalom also hosts the Jewish Day School, which is run by Chabad of Columbia. Organized in 1987 by Rabbi Hesh Epstein, Chabad initially held minyanim in Epstein’s living room. Today the Orthodox group is a vibrant congregation with its own home, the Chabad/Aleph House, as well as a team of spiritual leaders. The elementary day school, which opened in 1992 with 12 students, had 205 students in 2008.

In 2005, the Katie and Irwin Kahn Jewish Community Center was completed, replacing the decades-old facility built by Irwin’s father. Construction of the modern facility was made possible by the cooperative efforts of the members of Tree of Life and Beth Shalom, many of whom hold membership in both synagogues. The Community Center is located on the Gerry Sue and Norman Arnold Community Campus, also home to the Columbia Jewish Federation, the philanthropic arm of the Columbia Jewish community. Despite its relatively small size, Columbia’s Jewish community continues to grow and offer significant Jewish resources to its members.