Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Dillon/Latta, South Carolina

Overview >> South Carolina >> Dillon/Latta

Dillon/Latta: Historical Overview

|

The town of Dillon grew up around a railroad depot built amid pine trees on swampy land of little value, not far from the North Carolina border. This area of northeastern South Carolina, through which the Little Pee Dee River runs, was even more isolated than the state’s backcountry, delaying early settlement. Plans to build a rail line that ran directly from the South Carolina crossroads town of Florence to North Carolina, thereby circumventing the long trip eastward through Wilmington, were formulated in 1882. Negotiations for right of way fell flat, however, preventing the project from getting off the ground until wealthy merchant James Dillon came forward with a proposition. Dillon and his son Thomas purchased approximately 50 acres of land just east of the town of Little Rock. They exchanged right of way for a depot and a town named after the enterprising businessman. In 1888, the railroad reached the newly founded Dillon and a loading station was built a few miles to the south. The loading station would become the town of Latta, named for its surveyor, Robert Latta, a Confederate veteran from York County.

In the late 19th century, Jewish immigrants began to arrive in Dillon, Latta, and the surrounding towns, forming the base of a community that lasted almost to the end of the 20th century. |

RESOURCES

All photos courtesy of Special Collections, College of Charleston |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Dillon and Latta

The Latta

Dry Goods Co.

ca. 1906

The Latta

Dry Goods Co.

ca. 1906

Early Jewish Residents

In the late 19th century Jewish immigrants arrived and opened stores in Dillon and the surrounding towns. Abraham Schafer may have been the earliest Jew to settle in the area. German-born Schafer came to Darlington in the 1870s by way of New York and Charleston and worked for the Iseman family, who had sponsored his immigration. He married Issac Iseman’s daughter Rebecca, and they settled in Little Rock, where they opened a general store. The family of six lived above the store. Successful in the dry goods business, Abraham and Rebecca expanded their operation, opening two more stores in Dillon and Latta. When two of their daughters married, they turned the newest stores over to the newlyweds. Belle Schafer and Isadore Blum took over the Dillon store while Lizzie Schafer and her husband Leon Kornblut began operating the Latta Dry Goods Company soon after they were married in 1906. The store, which advertised itself in 1913 as the “Leaders in Ladies and Gents Furnishings,” occupied the same building as the Latta Hotel.

The small Jewish community of Dillon was often linked by kinship ties. Leon Kornblut had emigrated from Austria in 1896 when he was 17 years old. Like Abraham Schafer, he passed through New York and Charleston first before following his brother to Latta. Leon partnered with his brother-in-law Isadore Blum during the 1920s. At one time, Blum and Kornblut had as many as eight stores scattered throughout the area, staffed by Jews they hired out of Baltimore. Bankruptcy forced them to close their doors in 1928, however, and the two went their separate ways. Blum opened a store just across the state line in Rowland, North Carolina. Kornblut became a well-established businessman who was actively involved in Dillon County’s civic affairs. He opened Kornblut’s Department Store with “fashions for the entire family” in two locations, Dillon and Latta. He was active in civic affairs, serving as a director of the Dillon Merchants Association and the Dillon Industrial Corporation.

In the late 19th century Jewish immigrants arrived and opened stores in Dillon and the surrounding towns. Abraham Schafer may have been the earliest Jew to settle in the area. German-born Schafer came to Darlington in the 1870s by way of New York and Charleston and worked for the Iseman family, who had sponsored his immigration. He married Issac Iseman’s daughter Rebecca, and they settled in Little Rock, where they opened a general store. The family of six lived above the store. Successful in the dry goods business, Abraham and Rebecca expanded their operation, opening two more stores in Dillon and Latta. When two of their daughters married, they turned the newest stores over to the newlyweds. Belle Schafer and Isadore Blum took over the Dillon store while Lizzie Schafer and her husband Leon Kornblut began operating the Latta Dry Goods Company soon after they were married in 1906. The store, which advertised itself in 1913 as the “Leaders in Ladies and Gents Furnishings,” occupied the same building as the Latta Hotel.

The small Jewish community of Dillon was often linked by kinship ties. Leon Kornblut had emigrated from Austria in 1896 when he was 17 years old. Like Abraham Schafer, he passed through New York and Charleston first before following his brother to Latta. Leon partnered with his brother-in-law Isadore Blum during the 1920s. At one time, Blum and Kornblut had as many as eight stores scattered throughout the area, staffed by Jews they hired out of Baltimore. Bankruptcy forced them to close their doors in 1928, however, and the two went their separate ways. Blum opened a store just across the state line in Rowland, North Carolina. Kornblut became a well-established businessman who was actively involved in Dillon County’s civic affairs. He opened Kornblut’s Department Store with “fashions for the entire family” in two locations, Dillon and Latta. He was active in civic affairs, serving as a director of the Dillon Merchants Association and the Dillon Industrial Corporation.

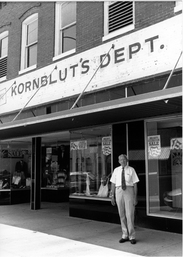

Kornblut's

Department

Store.

Kornblut's

Department

Store. Photo by Dale Rosengarten

A Growing Community

The Jewish community grew as small numbers of immigrants from Eastern Europe settled in the area. Isadore Cohen came to America from Lithuania in 1910 to avoid conscription into the Russian army. He and his siblings followed a brother to Baltimore. His brother Harry, who had ventured south peddling, urged Isadore to make his way to South Carolina, insisting he could make a decent living. The five dollars he sent took Isadore as far as Dillon, where he peddled before taking a job with one of the Blums in Latta. At some point, he opened his own small store with credit extended by the Baltimore Bargain House. Cohen’s clothing store, which catered to local tenant farmers, thrived and the business grew. His son Leonard joined him once he was discharged from the military at the end of World War II. Leonard kept the store running until 1987, when he finally closed its doors for the last time. His children, who had professional careers that took them away from home, were not poised to take over the family business, and competition from the large chain stores had become too fierce.

While many of these Jews came from Orthodox backgrounds, they often found it difficult to maintain their religious traditions in northeast South Carolina. The Kornblut family and others tried to keep the Jewish dietary laws as best they could, getting kosher meat sent down by train from Baltimore. Despite their desire to maintain Jewish traditions, the Kornbluts had to adjust their religious practices. Since their customers were largely local farmers, they had to keep their stores open on Saturdays since that was when they came to town to do their shopping. They did close their store each year on the Jewish High Holidays. Growing up in Latta, Moses Kornblut had a number of Christian friends and encountered no real anti-Semitism. After graduating from high school in 1932, he went straight to work for his father Leon, who expected his sons to follow him into the family business. When Leon retired, Moses took over the Latta store, while his brother Sigmond managed the Dillon store.

Many of these Jews enjoyed commercial success in Dillon, becoming active in the town’s civic life. Merchant Morris Fass settled in Dillon before the lines for the new Dillon County had been drawn in 1910. The Austrian immigrated to the United States as a child and lived in Charleston and Lake City for a time. He and Rosa Nachman of Charleston married, moved to Dillon, and opened a small store that over the years grew into the large Fass Department Store. They also acquired a significant amount of land, including farmland which they rented to tenants. Morris was active in civic life, playing key roles in the Dillon Chamber of Commerce and the Dillon Board of Trade. He was a Dillon alderman, a Mason, and a charter member of the Dillon Rotary Club. Morris’ brother Max also settled in Dillon, opening a store. A Mason and a Shriner, Max also made his living in the insurance and real estate business.

The Jewish community grew as small numbers of immigrants from Eastern Europe settled in the area. Isadore Cohen came to America from Lithuania in 1910 to avoid conscription into the Russian army. He and his siblings followed a brother to Baltimore. His brother Harry, who had ventured south peddling, urged Isadore to make his way to South Carolina, insisting he could make a decent living. The five dollars he sent took Isadore as far as Dillon, where he peddled before taking a job with one of the Blums in Latta. At some point, he opened his own small store with credit extended by the Baltimore Bargain House. Cohen’s clothing store, which catered to local tenant farmers, thrived and the business grew. His son Leonard joined him once he was discharged from the military at the end of World War II. Leonard kept the store running until 1987, when he finally closed its doors for the last time. His children, who had professional careers that took them away from home, were not poised to take over the family business, and competition from the large chain stores had become too fierce.

While many of these Jews came from Orthodox backgrounds, they often found it difficult to maintain their religious traditions in northeast South Carolina. The Kornblut family and others tried to keep the Jewish dietary laws as best they could, getting kosher meat sent down by train from Baltimore. Despite their desire to maintain Jewish traditions, the Kornbluts had to adjust their religious practices. Since their customers were largely local farmers, they had to keep their stores open on Saturdays since that was when they came to town to do their shopping. They did close their store each year on the Jewish High Holidays. Growing up in Latta, Moses Kornblut had a number of Christian friends and encountered no real anti-Semitism. After graduating from high school in 1932, he went straight to work for his father Leon, who expected his sons to follow him into the family business. When Leon retired, Moses took over the Latta store, while his brother Sigmond managed the Dillon store.

Many of these Jews enjoyed commercial success in Dillon, becoming active in the town’s civic life. Merchant Morris Fass settled in Dillon before the lines for the new Dillon County had been drawn in 1910. The Austrian immigrated to the United States as a child and lived in Charleston and Lake City for a time. He and Rosa Nachman of Charleston married, moved to Dillon, and opened a small store that over the years grew into the large Fass Department Store. They also acquired a significant amount of land, including farmland which they rented to tenants. Morris was active in civic life, playing key roles in the Dillon Chamber of Commerce and the Dillon Board of Trade. He was a Dillon alderman, a Mason, and a charter member of the Dillon Rotary Club. Morris’ brother Max also settled in Dillon, opening a store. A Mason and a Shriner, Max also made his living in the insurance and real estate business.

Ohav Shalom

Dillon SC

Ohav Shalom

Dillon SC

Photo by Dale Rosengarten

Organized Jewish Life in Dillon

Max and Morris Fass appear to have been the catalysts in establishing Dillon‘s first Jewish religious organization. By 1915, the Dillon Hebrew Congregation had formed and was meeting at one or the other of the Fass homes for services during these early years. Other charter members included Adolph and Hyman Witcover, William Brick, and Sam Levin. Morris Fass served as the lay leader. Laymen from South Carolina and neighboring states were hired to read on the High Holy Days. The small number of worshipers, mostly merchants, came from the surrounding small towns. Some of the participants were peddlers.

The group purchased a Torah in 1920 for three hundred dollars and members agreed “this Torah shall not be the property of any one member, but shall belong to all regardless of each individual’s contribution.” In 1922, the congregation hired reform Rabbi Jacob S. Raisin of Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim in Charleston to conduct services one Sunday a month. Around the same time, Fannie Brick organized a Sunday school under the supervision of Rabbi Raisin. Classes were held in the home of Max and Teresa Fass, utilizing lay teachers in the absence of the rabbi. Later, the congregation met in Dillon’s Masonic Temple.

In 1928, the congregation and its Sunday school changed its name to the Teresa Witcover Fass Congregation in honor of Max Fass’ wife who died in 1927 at the age of 48. Born in Marion, South Carolina, Teresa was the daughter of merchant Samuel Witcover. Her obituary in the Dillon Herald reported that although she had suffered for years from a chronic illness, her progress had been encouraging. Thus, her death a day after the onset of an acute episode “was a shock to the entire community.”

Teresa’s legacy was her generous and goodhearted nature, known to many Dillon area residents. Congregation members, years later, recalled that her “home was a haven for local Jewry.” This legacy may have prompted the women of the Dillon Hebrew Congregation to action. Two months after Teresa’s death, 21 female members of the congregation founded the Teresa Witcover Fass Sisterhood. The members of the Sisterhood, who were the backbone of the religious school, hosted holiday celebrations, participated in charitable work, and raised money to build a synagogue. In the early 1930s, they joined the National Federation of Temple Sisterhoods.

During the 1930s, the Jewish communities of Dillon and Latta reached their peak in population. According to a 1937 study, 84 Jews lived in Dillon while 75 lived in Latta at the time. Despite this sizable community, the small congregation struggled during the Great Depression, especially after the death of brothers Morris and Max Fass, who had been key organizers and participants, in 1935. Looking back, members report that with their deaths “the struggling congregation lost two faithful and long time members.” The congregation became largely inactive until 1939, when they hired Rabbi Samuel R. Shillman of Sumter’s Temple Sinai to lead services periodically. Under Shillman’s leadership, the congregation was reorganized and became active once again.

After the congregation was reorganized in 1939, it was officially incorporated. Sam Schafer of Little Rock, Abraham’s son, was the first president of the rejuvenated organization. At Shillman’s suggestion, the reform congregation changed its name to Ohav Shalom, or Lovers of Peace. Soon thereafter, the group purchased land on which to build a synagogue. With the support of about 20 families, building began early in 1942 with the laying of the cornerstone in a ceremony conducted by Shillman. The synagogue, fully paid for, was dedicated in November, that same year.

Max and Morris Fass appear to have been the catalysts in establishing Dillon‘s first Jewish religious organization. By 1915, the Dillon Hebrew Congregation had formed and was meeting at one or the other of the Fass homes for services during these early years. Other charter members included Adolph and Hyman Witcover, William Brick, and Sam Levin. Morris Fass served as the lay leader. Laymen from South Carolina and neighboring states were hired to read on the High Holy Days. The small number of worshipers, mostly merchants, came from the surrounding small towns. Some of the participants were peddlers.

The group purchased a Torah in 1920 for three hundred dollars and members agreed “this Torah shall not be the property of any one member, but shall belong to all regardless of each individual’s contribution.” In 1922, the congregation hired reform Rabbi Jacob S. Raisin of Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim in Charleston to conduct services one Sunday a month. Around the same time, Fannie Brick organized a Sunday school under the supervision of Rabbi Raisin. Classes were held in the home of Max and Teresa Fass, utilizing lay teachers in the absence of the rabbi. Later, the congregation met in Dillon’s Masonic Temple.

In 1928, the congregation and its Sunday school changed its name to the Teresa Witcover Fass Congregation in honor of Max Fass’ wife who died in 1927 at the age of 48. Born in Marion, South Carolina, Teresa was the daughter of merchant Samuel Witcover. Her obituary in the Dillon Herald reported that although she had suffered for years from a chronic illness, her progress had been encouraging. Thus, her death a day after the onset of an acute episode “was a shock to the entire community.”

Teresa’s legacy was her generous and goodhearted nature, known to many Dillon area residents. Congregation members, years later, recalled that her “home was a haven for local Jewry.” This legacy may have prompted the women of the Dillon Hebrew Congregation to action. Two months after Teresa’s death, 21 female members of the congregation founded the Teresa Witcover Fass Sisterhood. The members of the Sisterhood, who were the backbone of the religious school, hosted holiday celebrations, participated in charitable work, and raised money to build a synagogue. In the early 1930s, they joined the National Federation of Temple Sisterhoods.

During the 1930s, the Jewish communities of Dillon and Latta reached their peak in population. According to a 1937 study, 84 Jews lived in Dillon while 75 lived in Latta at the time. Despite this sizable community, the small congregation struggled during the Great Depression, especially after the death of brothers Morris and Max Fass, who had been key organizers and participants, in 1935. Looking back, members report that with their deaths “the struggling congregation lost two faithful and long time members.” The congregation became largely inactive until 1939, when they hired Rabbi Samuel R. Shillman of Sumter’s Temple Sinai to lead services periodically. Under Shillman’s leadership, the congregation was reorganized and became active once again.

After the congregation was reorganized in 1939, it was officially incorporated. Sam Schafer of Little Rock, Abraham’s son, was the first president of the rejuvenated organization. At Shillman’s suggestion, the reform congregation changed its name to Ohav Shalom, or Lovers of Peace. Soon thereafter, the group purchased land on which to build a synagogue. With the support of about 20 families, building began early in 1942 with the laying of the cornerstone in a ceremony conducted by Shillman. The synagogue, fully paid for, was dedicated in November, that same year.

Members of

Ohav Shalom

put their

building up for

sale in 1995.

Members of

Ohav Shalom

put their

building up for

sale in 1995.

Photo by Dale Rosengarten

Rabbi Shillman’s service to Sumter ended in 1948. It’s unclear if he continued to serve Dillon until that time, although it’s likely that he did. The congregation hired a number of rabbis in the ensuing decades whose backgrounds ranged from Reform to Orthodox. J. Aaron Levy of Sumter, Avery Grossfield of Florence, and a circuit-riding rabbi were among those who came from North Carolina and South Carolina to conduct Sabbath services one Sunday a month. A congregational history makes special mention of Rabbi Murray Alstett of Fayetteville, North Carolina, “who served this congregation long and faithfully.” Student rabbis were hired to lead High Holy Days services. Friday evening services, led by lay readers, were not routinely held until November 1954.

Sisterhood meetings and religious school classes were held in the synagogue and, in later years, in the congregation’s community center, built in 1956. During the 1950s, the Dillon Temple Sisterhood, as it later came to be called, established a fund to buy books for the synagogue’s library, held interfaith community events, and joined the National Women’s League. They were the only South Carolina Sisterhood to belong to the Conservative Jewish group, one they believed “would serve the Sisterhood’s needs further.”

The Sisterhood’s association with the Women’s League reflected a general trend among members of the congregation toward the Conservative movement. Member Moses Kornblut reported that the congregation made the shift from Reform to Conservative after reorganizing in 1939. The group’s willingness to hire rabbis of varying backgrounds suggests the lines between the traditions were blurred, most likely a necessity for such a small congregation.

Acquiring a burial ground was not a high priority of the Dillon congregation, perhaps because of its small size. Members may have felt it was not necessary given the availability of plots in Florence, nearly 30 miles southwest of Dillon. Many Jews from the Dillon and Latta region have been and continue to be buried in Florence’s Jewish Cemetery, established in the late 1880s. By the 1960s, however, Ohav Shalom did acquire a small portion of land within the boundaries of Greenlawn Memorial Park Cemetery in Dillon. Hebrew Garden’s first burials took place in 1967, and by 2003, 25 burials had been recorded.

In 1964, the Ohav Shalom Congregation celebrated its 25th anniversary. At that time, the group was 25 member families strong. Slightly less than half lived in Dillon, while the rest made their homes in the neighboring towns of Marion, Clio, Latta, Hamer, McColl, Mullins, Florence, and Fairmount, North Carolina. Two years prior, the small but thriving congregation had added a third building, used for educational purposes. Rabbi Charles B. Lesser, who led Florence’s Beth Israel Congregation from 1961-1970, served the Dillon Congregation on a part-time basis. From its reorganization in 1939 until 1964, the congregation celebrated 16 confirmations and eight bar mitzvahs. Ohav Shalom maintained its membership numbers through the 1970s and into the early 1980s. Despite its small size, the congregation never experienced problems due to insufficient funds.

Sisterhood meetings and religious school classes were held in the synagogue and, in later years, in the congregation’s community center, built in 1956. During the 1950s, the Dillon Temple Sisterhood, as it later came to be called, established a fund to buy books for the synagogue’s library, held interfaith community events, and joined the National Women’s League. They were the only South Carolina Sisterhood to belong to the Conservative Jewish group, one they believed “would serve the Sisterhood’s needs further.”

The Sisterhood’s association with the Women’s League reflected a general trend among members of the congregation toward the Conservative movement. Member Moses Kornblut reported that the congregation made the shift from Reform to Conservative after reorganizing in 1939. The group’s willingness to hire rabbis of varying backgrounds suggests the lines between the traditions were blurred, most likely a necessity for such a small congregation.

Acquiring a burial ground was not a high priority of the Dillon congregation, perhaps because of its small size. Members may have felt it was not necessary given the availability of plots in Florence, nearly 30 miles southwest of Dillon. Many Jews from the Dillon and Latta region have been and continue to be buried in Florence’s Jewish Cemetery, established in the late 1880s. By the 1960s, however, Ohav Shalom did acquire a small portion of land within the boundaries of Greenlawn Memorial Park Cemetery in Dillon. Hebrew Garden’s first burials took place in 1967, and by 2003, 25 burials had been recorded.

In 1964, the Ohav Shalom Congregation celebrated its 25th anniversary. At that time, the group was 25 member families strong. Slightly less than half lived in Dillon, while the rest made their homes in the neighboring towns of Marion, Clio, Latta, Hamer, McColl, Mullins, Florence, and Fairmount, North Carolina. Two years prior, the small but thriving congregation had added a third building, used for educational purposes. Rabbi Charles B. Lesser, who led Florence’s Beth Israel Congregation from 1961-1970, served the Dillon Congregation on a part-time basis. From its reorganization in 1939 until 1964, the congregation celebrated 16 confirmations and eight bar mitzvahs. Ohav Shalom maintained its membership numbers through the 1970s and into the early 1980s. Despite its small size, the congregation never experienced problems due to insufficient funds.

Moses Kornblut

in front of his

store, 1995.

Moses Kornblut

in front of his

store, 1995.

Photo by Dale Rosengarten

The Community Declines

By the early 1990s, however, there were only a handful of Jewish families left in Dillon. The congregation’s membership declined as a result of members moving out of the area or dying. Intermarriage and conversions to Christianity during the previous decades also played a role in the decline. In 1993, the seven remaining members agreed to close and sell the synagogue. The proceeds from the sale, plus funds remaining in the Sisterhood and congregation accounts, were split seven ways with the stipulation that the recipients would donate the money to the Jewish charity of their choice. The majority gave their portion to Florence’s Temple Beth Israel, the congregation most of them joined.

Jewish Contributions to Dillon and Latta

Although Dillon and Latta’s Jewish community dwindled to so few that they were absorbed by the Florence congregation, they have made a lasting mark on the region. Moses Kornblut served as a Latta City Council member for nearly 50 years. In 1993, the Latta Rotary Club honored Kornblut by naming him Citizen of the Year. Kornblut was also active within the local Jewish community. Over the years, he served as president, treasurer, and secretary for Ohav Shalom. A devoted member of the congregation, he filled many other roles as well, serving as lay reader and organizer of High Holy Day services. He was also a founding member and past president of the Dillon B’nai B’rith Lodge. In 2008, Kornblut, in his early nineties, not only still served on city council and was the Mayor Pro Tem, but he continued to operate Kornblut’s Department Store, the last Jewish-owned store in the area.

By the early 1990s, however, there were only a handful of Jewish families left in Dillon. The congregation’s membership declined as a result of members moving out of the area or dying. Intermarriage and conversions to Christianity during the previous decades also played a role in the decline. In 1993, the seven remaining members agreed to close and sell the synagogue. The proceeds from the sale, plus funds remaining in the Sisterhood and congregation accounts, were split seven ways with the stipulation that the recipients would donate the money to the Jewish charity of their choice. The majority gave their portion to Florence’s Temple Beth Israel, the congregation most of them joined.

Jewish Contributions to Dillon and Latta

Although Dillon and Latta’s Jewish community dwindled to so few that they were absorbed by the Florence congregation, they have made a lasting mark on the region. Moses Kornblut served as a Latta City Council member for nearly 50 years. In 1993, the Latta Rotary Club honored Kornblut by naming him Citizen of the Year. Kornblut was also active within the local Jewish community. Over the years, he served as president, treasurer, and secretary for Ohav Shalom. A devoted member of the congregation, he filled many other roles as well, serving as lay reader and organizer of High Holy Day services. He was also a founding member and past president of the Dillon B’nai B’rith Lodge. In 2008, Kornblut, in his early nineties, not only still served on city council and was the Mayor Pro Tem, but he continued to operate Kornblut’s Department Store, the last Jewish-owned store in the area.

The giant

"Pedro" sign

welcomes

motorists to

The giant

"Pedro" sign

welcomes

motorists to

South of the Border, founded by Alan Schafer

Perhaps the most notable business in the area is “South of the Border,” which was founded by Dillon native Alan Schafer. Schafer had been a journalism major at the University of South Carolina when he left his academic pursuits behind to join his father in business. He convinced his father Sam to sell the family store and concentrate solely on selling beer. The Schafer Distributing Company was launched in 1933. They struggled through the Depression years, selling beer they had bought in Baltimore from the back of a truck. In the mid-to-late 1940s, a North Carolina county bordering South Carolina changed its alcohol licensing laws, limiting sales. Alan seized the opportunity by setting up a beer stand not far from the state line. The acreage he bought was near the north-south highway connecting New York and Miami, which later would be supplanted by Interstate 95. In this ideal location, Alan’s beer business expanded exponentially over the years to become “South of the Border,” with Mexican-themed amusement park rides, hotels, restaurants, and gift shops. Schafer put up 120 billboards along the interstate advertising for his kitschy tourist attraction, which was one of the first rest stops in the state to accommodate both blacks and whites in the 1950s. Even though Schafer died in 2001, South of the Border’s giant Pedro statue still welcomes motorists today.

Ben

Bernanke

Ben

Bernanke

If South of the Border represents one end of the business spectrum, another Dillon Jew, Ben Bernanke, ascended the heights of the other end, becoming a leader of the financial world. Jonas and Pauline Bernanke, who immigrated to the United States from Austria in the 1920s, moved to Dillon in the early 1940s and opened the Jay Bee Drug Company. Jonas was a pharmacist and Lina was a physician. Sons Philip and Mortimer succeeded them in the business. The Bernankes were actively involved in the Ohav Shalom Congregation. Philip and his wife Edna hosted the student rabbis hired by the congregation since they were the only family in the area that kept kosher. Their son, Ben, who waited tables at South of the Border during his summers while a college student at Harvard, went on to have a successful academic career as an economist. In 2006, he was appointed Chairman of the Federal Reserve upon Alan Greenspan’s retirement. That same year, Dillon County and the South Carolina legislature honored Ben by declaring the first of September Ben Bernanke Day and presenting him with the Order of the Palmetto, the state’s greatest civilian award, in recognition of his accomplishments.

The Jewish Community in Dillon/Latta Today

Today, only a handful of Jews remain in Dillon and its surrounding towns. Most have become a part of the nearby Jewish community of Florence.