Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Georgetown, South Carolina

Overview >> South Carolina >> Georgetown

Georgetown: Historical Overview

|

Georgetown, an hour’s drive north of Charleston, is situated on the Sampit River near the mouth of Winyah Bay. The Sampit is one of a handful of rivers that empty into the bay and its waters advance and retreat according to the tides, an ideal setting for growing rice. In the 1720s, the colonists in the parish of Prince George Winyah, wishing to save time and money by exporting naval stores and rice directly from Winyah rather than through Charleston, appealed to the British government for their own port. As a result, Georgetown (George Town until 1798) was established in 1732 as an official port of entry. By the 1730s, rice had become an economic mainstay and would remain so until the Civil War. Georgetown plantation owners dramatically increased their wealth in the decades before the Revolution by growing indigo as well, a plant that produced a blue dye in heavy demand in Europe.

Jews have lived in Georgetown since the 1760s, playing an important role in the development of the town. The Jewish community continues to be an active part of Georgetown today. |

RESOURCES

Temple Beth Elohim website All photos courtesy of Special Collections, College of Charleston |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Georgetown

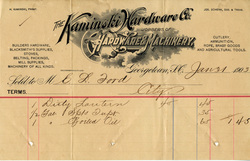

1903 receipt from the Kaminski Hardware Company

1903 receipt from the Kaminski Hardware Company

Early Settlers

When the first Jewish settlers arrived in Georgetown, the area’s economy was dominated by planters. Abraham and Solomon Cohen moved from Charleston to Georgetown in the early 1760s. Sons of Rabbi Moses Cohen of Charleston’s Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim, they had emigrated from London with their father in 1750. Mordecai Myers arrived in Georgetown about the same time as the Cohen brothers. Information regarding Myers is limited. However, the Cohens became successful merchants and men of prominence, active participants in public affairs and social organizations. Abraham Cohen was a Mason, a founder of the Georgetown Library Society and the Georgetown Fire Company, and a commissioner of streets and markets. Solomon Cohen was a member of the Library Society, a sergeant in the Winyah Light Dragoons, a tax collector, and intendant, or mayor, of Georgetown in 1818. Both men served as postmasters and were members of the Winyah Indigo Society, a fraternal association with intellectual leanings, responsible for opening a school for children.

The Jewish population grew significantly in the decades after the Cohens and Myers arrived. It is believed that by 1800, about 80 Jews, roughly ten percent of the white population, lived in the town, making it the second oldest and the second largest Jewish community in South Carolina after Charleston. The names of Georgetown Jews appear in Charleston’s Beth Elohim records, suggesting they maintained ties to the Charleston community. As was customary, in 1772, soon after the first Jews arrived, a Jewish cemetery was established in Georgetown. Yet, there is no evidence that this sizable and active Jewish contingent tried to form their own congregation.

The second generation of Myers and Cohens were successful in a variety of careers and deeply engaged in community affairs, as was the case with other antebellum Jewish settlers, such as the Joseph, Solomon, Solomons, Moses, Aronson, Hart, Woolf, Sasportas, Emsden, Henry, Lopez, Sampson, and Emanuel families. Vital contributors to the local economy, these Jews were merchants, businessmen, lawyers, auctioneers, port agents, bank directors, pharmacists, and physicians. Solomon Cohen, Jr., was a planter. Records indicate Jewish men also maintained a high level of involvement in town life through government service, holding positions such as warden, clerk of court, tax collector, coroner, commissioner, postmaster, customs inspector, state legislator, and intendant. Three of the seven Jews who have served as mayor in Georgetown’s history held the position prior to the Civil War.

Most of the Jewish residents of Georgetown owned slaves, usually only a few at a time, as was typical of members of the merchant and business class. Solomon Cohen, Jr., owned 20, considerably fewer than most plantation owners. Like other antebellum merchants, Jews engaged in the slave trade. The politics of slavery found Georgetown Jews on both sides of the debate in the opposing political parties and at the Nullification Convention of 1832. Despite the divide among them over slavery, Georgetown Jews rallied behind the Confederacy once the war broke out. Five who died fighting for the South are buried in the Jewish cemetery.

When the first Jewish settlers arrived in Georgetown, the area’s economy was dominated by planters. Abraham and Solomon Cohen moved from Charleston to Georgetown in the early 1760s. Sons of Rabbi Moses Cohen of Charleston’s Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim, they had emigrated from London with their father in 1750. Mordecai Myers arrived in Georgetown about the same time as the Cohen brothers. Information regarding Myers is limited. However, the Cohens became successful merchants and men of prominence, active participants in public affairs and social organizations. Abraham Cohen was a Mason, a founder of the Georgetown Library Society and the Georgetown Fire Company, and a commissioner of streets and markets. Solomon Cohen was a member of the Library Society, a sergeant in the Winyah Light Dragoons, a tax collector, and intendant, or mayor, of Georgetown in 1818. Both men served as postmasters and were members of the Winyah Indigo Society, a fraternal association with intellectual leanings, responsible for opening a school for children.

The Jewish population grew significantly in the decades after the Cohens and Myers arrived. It is believed that by 1800, about 80 Jews, roughly ten percent of the white population, lived in the town, making it the second oldest and the second largest Jewish community in South Carolina after Charleston. The names of Georgetown Jews appear in Charleston’s Beth Elohim records, suggesting they maintained ties to the Charleston community. As was customary, in 1772, soon after the first Jews arrived, a Jewish cemetery was established in Georgetown. Yet, there is no evidence that this sizable and active Jewish contingent tried to form their own congregation.

The second generation of Myers and Cohens were successful in a variety of careers and deeply engaged in community affairs, as was the case with other antebellum Jewish settlers, such as the Joseph, Solomon, Solomons, Moses, Aronson, Hart, Woolf, Sasportas, Emsden, Henry, Lopez, Sampson, and Emanuel families. Vital contributors to the local economy, these Jews were merchants, businessmen, lawyers, auctioneers, port agents, bank directors, pharmacists, and physicians. Solomon Cohen, Jr., was a planter. Records indicate Jewish men also maintained a high level of involvement in town life through government service, holding positions such as warden, clerk of court, tax collector, coroner, commissioner, postmaster, customs inspector, state legislator, and intendant. Three of the seven Jews who have served as mayor in Georgetown’s history held the position prior to the Civil War.

Most of the Jewish residents of Georgetown owned slaves, usually only a few at a time, as was typical of members of the merchant and business class. Solomon Cohen, Jr., owned 20, considerably fewer than most plantation owners. Like other antebellum merchants, Jews engaged in the slave trade. The politics of slavery found Georgetown Jews on both sides of the debate in the opposing political parties and at the Nullification Convention of 1832. Despite the divide among them over slavery, Georgetown Jews rallied behind the Confederacy once the war broke out. Five who died fighting for the South are buried in the Jewish cemetery.

After the Civil War

The number of Jews living in Georgetown after the Civil War dropped to a reported 54, a downward trend seen in other South Carolina towns in the post-war era. Those who remained, however, continued to be active in the town’s economic, political, and social life. During and after Reconstruction, the Sampson and Emanuel mercantile businesses thrived, joined by newcomers Elkan Baum and Heiman Kaminski, who became successful businessmen and respected members of the community. A network of business and marriage ties connected these families. Sol Emanuel gave up his father’s business to partner with Heiman Kaminski, his brother-in-law. Emanuel was a leader in the Georgetown Rifle Guards and was elected intendant in 1876 and 1877. Kaminski, who had emigrated from Prussia to the United States in 1854, worked in Baum’s Conwayboro store before joining the Confederate Army. After the war, Kaminski settled in Georgetown and opened a dry goods store with Emanuel and a third partner. From his modest start, Kaminski’s prosperity reached impressive heights. He added one business after another, broadening his reach into hardware, medical supplies, boats, and shipping. He was co-owner of the schooner, the Linah C. Kaminski, named for his mother, and vice president of the Bank of Georgetown. He also served as a director of the Georgetown Rice Milling Company, the Georgetown Telegraph Company, and the Georgetown and Lanes Railroad. In 1882, he was one of seven new owners of a telephone.

Brothers Joseph and Samuel Sampson successfully revived their mercantile business after the Civil War, expanding their interests to include shipping as well. Louis S. Ehrich, Joseph’s son-in-law, became a partner in the company, served as a superintendent of the Georgetown Rice Milling Company, director of the Georgetown Telegraph Company and the Georgetown and Lanes Railroad, and secretary-treasurer of the Board of Pilot Commissioners. He was elected intendant for three terms starting in 1886.

Kaminski and his peers were primary figures in the growth of the town in the latter half of the 19th century. Socially prominent and financially well off, they spurred modernization by extending rail lines, opening communications, and supporting economic enterprise. They were an integral part of Georgetown life, but apparently invested no energy or money in developing Jewish organizations. It was their insular and cohesive immigrant successors, the Jews of Eastern Europe, who created Georgetown’s 20th century Jewish institutions.

The number of Jews living in Georgetown after the Civil War dropped to a reported 54, a downward trend seen in other South Carolina towns in the post-war era. Those who remained, however, continued to be active in the town’s economic, political, and social life. During and after Reconstruction, the Sampson and Emanuel mercantile businesses thrived, joined by newcomers Elkan Baum and Heiman Kaminski, who became successful businessmen and respected members of the community. A network of business and marriage ties connected these families. Sol Emanuel gave up his father’s business to partner with Heiman Kaminski, his brother-in-law. Emanuel was a leader in the Georgetown Rifle Guards and was elected intendant in 1876 and 1877. Kaminski, who had emigrated from Prussia to the United States in 1854, worked in Baum’s Conwayboro store before joining the Confederate Army. After the war, Kaminski settled in Georgetown and opened a dry goods store with Emanuel and a third partner. From his modest start, Kaminski’s prosperity reached impressive heights. He added one business after another, broadening his reach into hardware, medical supplies, boats, and shipping. He was co-owner of the schooner, the Linah C. Kaminski, named for his mother, and vice president of the Bank of Georgetown. He also served as a director of the Georgetown Rice Milling Company, the Georgetown Telegraph Company, and the Georgetown and Lanes Railroad. In 1882, he was one of seven new owners of a telephone.

Brothers Joseph and Samuel Sampson successfully revived their mercantile business after the Civil War, expanding their interests to include shipping as well. Louis S. Ehrich, Joseph’s son-in-law, became a partner in the company, served as a superintendent of the Georgetown Rice Milling Company, director of the Georgetown Telegraph Company and the Georgetown and Lanes Railroad, and secretary-treasurer of the Board of Pilot Commissioners. He was elected intendant for three terms starting in 1886.

Kaminski and his peers were primary figures in the growth of the town in the latter half of the 19th century. Socially prominent and financially well off, they spurred modernization by extending rail lines, opening communications, and supporting economic enterprise. They were an integral part of Georgetown life, but apparently invested no energy or money in developing Jewish organizations. It was their insular and cohesive immigrant successors, the Jews of Eastern Europe, who created Georgetown’s 20th century Jewish institutions.

According to this 1894 receipt,

According to this 1894 receipt, Marks Moses & Bro. closed on Saturdays

The Turn of the 20th Century

Front Street, formerly Bay Street, was the heart of the business district. Jewish stores lining the street were a prominent part of economic life from the late 19th century well into the 20th century. Merchants named Moses, Flaum, Breslauer, Brilles, Fogel, Gladstone, Isear, Rosen, Schneider, Ringel, Schenk, Weinberg, and Dundas sold groceries, clothing, carpets, window shades, cotton, rice, naval stores, hay, oats, corn, jewelry, furniture, and appliances. An 1894 receipt from Marks Moses and Brother, general merchandisers, notes that the business was closed on Saturdays, suggesting the Moses brothers were observant Jews. Their closure, however, may have been an exception, rather than the norm. J. M. Ringel, who was considered the most observant Orthodox Georgetown Jew of the period, did not work on the Sabbath, but relied on his wife to open his store every Saturday. Because rural residents made their weekly trips to town on Saturdays, merchants felt they needed to open to stay competitive. Philip Schneider, who grew up in Georgetown in the years before the Depression, remembers Front Street stores doing business until midnight on Saturdays to take advantage of the crowds. Owners would station “pullers” outside their shops, men whose job it was to lure customers inside. In contrast to the bustling retail atmosphere of routine Saturdays, Georgetown “closed down” once a year when Jewish merchants observed the High Holy Days.

Front Street, formerly Bay Street, was the heart of the business district. Jewish stores lining the street were a prominent part of economic life from the late 19th century well into the 20th century. Merchants named Moses, Flaum, Breslauer, Brilles, Fogel, Gladstone, Isear, Rosen, Schneider, Ringel, Schenk, Weinberg, and Dundas sold groceries, clothing, carpets, window shades, cotton, rice, naval stores, hay, oats, corn, jewelry, furniture, and appliances. An 1894 receipt from Marks Moses and Brother, general merchandisers, notes that the business was closed on Saturdays, suggesting the Moses brothers were observant Jews. Their closure, however, may have been an exception, rather than the norm. J. M. Ringel, who was considered the most observant Orthodox Georgetown Jew of the period, did not work on the Sabbath, but relied on his wife to open his store every Saturday. Because rural residents made their weekly trips to town on Saturdays, merchants felt they needed to open to stay competitive. Philip Schneider, who grew up in Georgetown in the years before the Depression, remembers Front Street stores doing business until midnight on Saturdays to take advantage of the crowds. Owners would station “pullers” outside their shops, men whose job it was to lure customers inside. In contrast to the bustling retail atmosphere of routine Saturdays, Georgetown “closed down” once a year when Jewish merchants observed the High Holy Days.

Temple Beth Elohim was dedicated in 1950.

Temple Beth Elohim was dedicated in 1950.

Organized Jewish Life in Georgetown

An estimated 65 Jews were living in Georgetown in 1904 when Congregation Beth Elohim was organized, with plans for a Bible class and a Sunday school. Beth Elohim’s namesake and sister congregation in Charleston, which had made the transition from Orthodox to Reform in the mid-19th century, agreed to loan the services of Rabbi Elzas on alternate Sundays. The organization may have floundered in its early years since Esther Gladstone Rubin, who grew up in Georgetown during this period, does not remember any activity until 1917 when Rabbi Jacob S. Raisin of Charleston “reorganized” the congregation. Beth Elohim did not officially incorporate until 1921.

Lacking its own rabbi, the congregation’s activities depended on lay leadership. Debby Abrams recalls religious practices, when she arrived in 1942, as being primarily Reform, but with “a little bit of everything.” Services and Sunday school were held in a room in the Winyah Indigo Society Hall. J. M. Ringel led Sabbath services, bringing with him the Torah he owned. He also paid the fees of the rabbis hired to conduct High Holy Day services. Laymen taught Sunday school under the guidance of Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim’s Rabbi Raisin and his successor, Rabbi Allan Tarshish. With help from Charleston women, a Sisterhood was organized in 1938. Rita Levy Fogel remembers attending oneg Shabbat after the weekly services.

An unexplained yet significant delay occurred between incorporation and securing a building to house the congregation. The temple, with classrooms, a kitchen, and an assembly room was finally built in 1949 and dedicated in a 1950 ceremony led by Rabbi Tarshish, who had been serving the congregation of about 50 members once monthly. Before the dedication of Temple Beth Elohim, the Jewish children traveled to Charleston for confirmation ceremonies, while the boys were bar mitzvahed in Georgetown.

20th Century Jewish Life in Georgetown

Few Georgetown families kept kosher. Alwyn Goldstein, who moved in 1938 from Charleston to Georgetown to open a clothing store, described the Jews of Georgetown as “liberal.” His second wife was a Baptist, and they celebrated both Hanukkah and Christmas. Relations between Christians and Jews, Goldstein attested, reflected a close-knit community, with friendships crossing the lines among Protestant, Catholic, and Jew. Jews attended church celebrations with their Christian friends, who in turn, came to Jewish functions such as Purim parties. Jews still joined the Winyah Indigo Society, and in the 20th century, two more were elected mayor, Harold Kaminski (1930-1935) and Sylvan Rosen (1948-1961). The Jews of Georgetown continued to play an integral role in the community’s economy, social groups, and politics.

Beth Elohim’s membership declined after a reported peak in the 1950s, as the congregation’s children came of age and pursued opportunities elsewhere. By the mid-1990s, a dozen or fewer remained, prompting them to consider selling the temple and using the funds for cemetery maintenance. Alwyn Goldstein served as unofficial “rabbi,” acting as the lay reader for weekly services that lasted about 15 minutes. Young Jews were moving to the area, but few were coming to Beth Elohim. One member speculated that the occasional visitors they did receive were disappointed by the short service and the lack of sermon or discussion.

An estimated 65 Jews were living in Georgetown in 1904 when Congregation Beth Elohim was organized, with plans for a Bible class and a Sunday school. Beth Elohim’s namesake and sister congregation in Charleston, which had made the transition from Orthodox to Reform in the mid-19th century, agreed to loan the services of Rabbi Elzas on alternate Sundays. The organization may have floundered in its early years since Esther Gladstone Rubin, who grew up in Georgetown during this period, does not remember any activity until 1917 when Rabbi Jacob S. Raisin of Charleston “reorganized” the congregation. Beth Elohim did not officially incorporate until 1921.

Lacking its own rabbi, the congregation’s activities depended on lay leadership. Debby Abrams recalls religious practices, when she arrived in 1942, as being primarily Reform, but with “a little bit of everything.” Services and Sunday school were held in a room in the Winyah Indigo Society Hall. J. M. Ringel led Sabbath services, bringing with him the Torah he owned. He also paid the fees of the rabbis hired to conduct High Holy Day services. Laymen taught Sunday school under the guidance of Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim’s Rabbi Raisin and his successor, Rabbi Allan Tarshish. With help from Charleston women, a Sisterhood was organized in 1938. Rita Levy Fogel remembers attending oneg Shabbat after the weekly services.

An unexplained yet significant delay occurred between incorporation and securing a building to house the congregation. The temple, with classrooms, a kitchen, and an assembly room was finally built in 1949 and dedicated in a 1950 ceremony led by Rabbi Tarshish, who had been serving the congregation of about 50 members once monthly. Before the dedication of Temple Beth Elohim, the Jewish children traveled to Charleston for confirmation ceremonies, while the boys were bar mitzvahed in Georgetown.

20th Century Jewish Life in Georgetown

Few Georgetown families kept kosher. Alwyn Goldstein, who moved in 1938 from Charleston to Georgetown to open a clothing store, described the Jews of Georgetown as “liberal.” His second wife was a Baptist, and they celebrated both Hanukkah and Christmas. Relations between Christians and Jews, Goldstein attested, reflected a close-knit community, with friendships crossing the lines among Protestant, Catholic, and Jew. Jews attended church celebrations with their Christian friends, who in turn, came to Jewish functions such as Purim parties. Jews still joined the Winyah Indigo Society, and in the 20th century, two more were elected mayor, Harold Kaminski (1930-1935) and Sylvan Rosen (1948-1961). The Jews of Georgetown continued to play an integral role in the community’s economy, social groups, and politics.

Beth Elohim’s membership declined after a reported peak in the 1950s, as the congregation’s children came of age and pursued opportunities elsewhere. By the mid-1990s, a dozen or fewer remained, prompting them to consider selling the temple and using the funds for cemetery maintenance. Alwyn Goldstein served as unofficial “rabbi,” acting as the lay reader for weekly services that lasted about 15 minutes. Young Jews were moving to the area, but few were coming to Beth Elohim. One member speculated that the occasional visitors they did receive were disappointed by the short service and the lack of sermon or discussion.

The Jewish Community in Georgetown Today

Members of Beth Elohim stand before their ark in 2000.

Members of Beth Elohim stand before their ark in 2000. Photo by Bill Aron

By 2003, membership had dropped to five, all elderly, who continued their weekly meetings faithfully. They were as faithful to one another as they were to Judaism. They declined invitations from their out-of-town families to join them for the High Holy Days so that they could celebrate in Georgetown with their fellow members.

One year later, the congregation had grown to 47, thanks to the recruiting efforts of Elizabeth Moses, a newcomer to Georgetown. The Sumter native, a descendant of one of South Carolina’s earliest and most illustrious Jewish families and raised in the Roman Catholic Church, had recently converted to Judaism. Beth Elohim, made up mostly of retirees from the Northeast, has welcomed the increased and more active community.

One year later, the congregation had grown to 47, thanks to the recruiting efforts of Elizabeth Moses, a newcomer to Georgetown. The Sumter native, a descendant of one of South Carolina’s earliest and most illustrious Jewish families and raised in the Roman Catholic Church, had recently converted to Judaism. Beth Elohim, made up mostly of retirees from the Northeast, has welcomed the increased and more active community.