Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Greenville, South Carolina

Overview >> South Carolina >> Greenville

Greenville: Historical Overview

|

Greenville sits in the foothills of the Great Smoky Mountains, once part of Cherokee territory, in what is now the northwestern corner of South Carolina. Europeans began moving into this area of the upper Piedmont well before the region was formally opened to settlement in 1784. In 1794, Eleazar Elizar became postmaster of what was to become Greenville—making him its first Jewish resident, according to Rabbi Barnett Elzas. Originally named Pleasantburg, the village was laid out in 1797 near a new wagon road, but was slow to attract residents. A decade later, only half of the 52 lots had been sold and the settlement’s name had changed to Greenville Courthouse, or simply, Greenville. The new name is believed to have been in honor of the Revolutionary War hero, General Nathanael Greene of Rhode Island.

The district’s economy depended on small-scale agriculture and manufacturing. Farmers grew a variety of crops but, in contrast to their counterparts elsewhere in the state, produced very little cotton. Nevertheless, the area’s abundant water power facilitated the development of the textile industry and other enterprises, such as flour mills, iron foundries, and firearms manufacturing. In the antebellum era, the population swelled each summer when lowcountry planter families flocked to the resorts that grew up around the Upcountry’s mineral springs. The Jewish community continues to thrive in Greenville today. |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Greenville

Beth Israel's first synagogue

Beth Israel's first synagogue

Early Settlers

Credit reports of the commercial reporting agency R. G. Dun & Co. provide ample evidence of Jews living in Greenville in the 1850s, the decade the city welcomed Furman Academy and a rail connection to Columbia. Attorney Jack Bloom, Greenville native and community historian, authored A History of the Jewish Community of Greenville, South Carolina. In researching credit reports, city directories, and the United States Census, he relied, in part, on surnames to determine the background of those listed.

Bloom noted that the “first positive reference to a Jewish person or business” that he could find was Hoffman & Co., which appears in the 1850 records. He speculated that Hoffman was a German Jew who may have left Greenville in 1851. Next, Abraham Isaacs, a businessman, is listed in the 1855 records for the partnership, Nichols & Isaacs. After the Civil War, Isaacs is paired with Simon Swansdale in Swansdale & Isaacs. An 1855 credit document reports on the Baltimore Clothing Store and the Einstein Co. together, and refers to the owners of both companies as Jews. Simon Einstein and Joseph Sonenberg are listed under the Einstein Co. in 1857, while Lewis Einstein and Joseph Lewinburg appear in the 1859 records.

In the decades before the Civil War, the region grew at a slower pace than the rest of the state. By 1860, Greenville’s population was just over 1,800, with at least eight individuals with Jewish names listed in the census for that year. A. S. Salley’s South Carolina Troops in Confederate Service identifies two Jewish men who served in Greenville’s Butler’s Guards—Abraham Isaacs and Isaac W. Hirsch. The latter moved to Charleston after the war.

Morris Samuel, David Lowenberg, and Abigail and L. L. Levy appear in Dun & Co. reports for the late 1850s and early 1860s. These Jewish merchants lived in Greenville only briefly before moving on. Historian Archie Vernon Huff interpreted their short-lived residency and the negative comments on their credit reports as indications that “Greenville was clearly not hospitable to Jews.”

After the Civil War

By the early 1880s, Greenville, which had incorporated as a city a decade earlier, was booming, the economy fueled by new railroad connections, 149 stores, and farmers who, unlike their predecessors, were growing significant amounts of cotton. The yield continued to increase through 1920, by which time the county had become the state’s third largest producer of cotton, behind Orangeburg and Anderson. The area boasted seven textile mills by 1882 and, in the ensuing decades, their growth in both size and number kept pace with the surge in cotton cultivation. From 1890 to 1920, the population of Greenville, city and county, increased dramatically.

Jews played an active role in the emerging prosperity. As early as 1878, an estimated 35 Jews lived in Greenville. Harris Marks, a merchant who appears in the records from 1870 to 1900, had been in business in Union and Columbia, South Carolina, before the Civil War. Hyman Endel, whose name can be found in the Greenville directory from 1877 to 1925, partnered briefly in a clothing store with Marks. The 1880/1881 directory shows they also ran a saloon. It is believed that the two were related. Lee Rothschild, initially the manager of S. Brafman’s clothing store and, later, proprietor of his own men’s clothing store, appears in the city directory from 1880 to 1927. In 1896, he was a director of Piedmont Savings and Investments.

By the early 20th century, a growing numbers of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe were settling in Greenville. The Bloom family, headed by Jack Bloom’s grandfather, Harris, settled first in Columbia around 1905, and moved to Greenville by 1910. His son, Julius, joined him at Bloom’s Department Store after serving in World War I. Brothers Morris and Samuel Lurey, who had emigrated as teens from Russia around 1905, settled in Greenville five years later. Both opened dry goods stores and may have been founding members of Beth Israel. Samuel married Ida Switzer, whose family had moved to Greenville from New York in the 1890s seeking new business opportunities.

Credit reports of the commercial reporting agency R. G. Dun & Co. provide ample evidence of Jews living in Greenville in the 1850s, the decade the city welcomed Furman Academy and a rail connection to Columbia. Attorney Jack Bloom, Greenville native and community historian, authored A History of the Jewish Community of Greenville, South Carolina. In researching credit reports, city directories, and the United States Census, he relied, in part, on surnames to determine the background of those listed.

Bloom noted that the “first positive reference to a Jewish person or business” that he could find was Hoffman & Co., which appears in the 1850 records. He speculated that Hoffman was a German Jew who may have left Greenville in 1851. Next, Abraham Isaacs, a businessman, is listed in the 1855 records for the partnership, Nichols & Isaacs. After the Civil War, Isaacs is paired with Simon Swansdale in Swansdale & Isaacs. An 1855 credit document reports on the Baltimore Clothing Store and the Einstein Co. together, and refers to the owners of both companies as Jews. Simon Einstein and Joseph Sonenberg are listed under the Einstein Co. in 1857, while Lewis Einstein and Joseph Lewinburg appear in the 1859 records.

In the decades before the Civil War, the region grew at a slower pace than the rest of the state. By 1860, Greenville’s population was just over 1,800, with at least eight individuals with Jewish names listed in the census for that year. A. S. Salley’s South Carolina Troops in Confederate Service identifies two Jewish men who served in Greenville’s Butler’s Guards—Abraham Isaacs and Isaac W. Hirsch. The latter moved to Charleston after the war.

Morris Samuel, David Lowenberg, and Abigail and L. L. Levy appear in Dun & Co. reports for the late 1850s and early 1860s. These Jewish merchants lived in Greenville only briefly before moving on. Historian Archie Vernon Huff interpreted their short-lived residency and the negative comments on their credit reports as indications that “Greenville was clearly not hospitable to Jews.”

After the Civil War

By the early 1880s, Greenville, which had incorporated as a city a decade earlier, was booming, the economy fueled by new railroad connections, 149 stores, and farmers who, unlike their predecessors, were growing significant amounts of cotton. The yield continued to increase through 1920, by which time the county had become the state’s third largest producer of cotton, behind Orangeburg and Anderson. The area boasted seven textile mills by 1882 and, in the ensuing decades, their growth in both size and number kept pace with the surge in cotton cultivation. From 1890 to 1920, the population of Greenville, city and county, increased dramatically.

Jews played an active role in the emerging prosperity. As early as 1878, an estimated 35 Jews lived in Greenville. Harris Marks, a merchant who appears in the records from 1870 to 1900, had been in business in Union and Columbia, South Carolina, before the Civil War. Hyman Endel, whose name can be found in the Greenville directory from 1877 to 1925, partnered briefly in a clothing store with Marks. The 1880/1881 directory shows they also ran a saloon. It is believed that the two were related. Lee Rothschild, initially the manager of S. Brafman’s clothing store and, later, proprietor of his own men’s clothing store, appears in the city directory from 1880 to 1927. In 1896, he was a director of Piedmont Savings and Investments.

By the early 20th century, a growing numbers of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe were settling in Greenville. The Bloom family, headed by Jack Bloom’s grandfather, Harris, settled first in Columbia around 1905, and moved to Greenville by 1910. His son, Julius, joined him at Bloom’s Department Store after serving in World War I. Brothers Morris and Samuel Lurey, who had emigrated as teens from Russia around 1905, settled in Greenville five years later. Both opened dry goods stores and may have been founding members of Beth Israel. Samuel married Ida Switzer, whose family had moved to Greenville from New York in the 1890s seeking new business opportunities.

The first Temple of Israel

The first Temple of Israel

Organized Jewish Life in Greenville

Around 1910, these recent immigrants began to worship together, often led by Harris Bloom. In 1912, this Orthodox congregation hired Charles Zaglin, a Lithuanian immigrant living in Wilmington, North Carolina, as a rabbi, shochet, and mohel. Zaglin moved to Greenville and, at the insistence of his wife, Evelyn Rose, built a mikvah. A few years later, Charles gave up the position of rabbi, although he continued to serve as the community’s mohel and shochet. Zaglin opened a store offering kosher and non-kosher meat. According to his grandson, there weren’t enough Jews in Greenville to support a kosher-only market. The Orthodox group later adopted the name Beth Israel, and met in various rented rooms in Greenville. They had various rabbis during the 1920s, including Don Hechter and Jacob Aronson. Beth Israel began building its synagogue in the late 1920s on the north side of the city, where many of Greenville’s nearly 200 Jews lived at the time. Charles Zaglin donated the lot on Townes Street, and construction of the first phase, a hall, was completed in 1930. The sanctuary, located on the upper level, was added a few years later.

Around the same time as the founding of the Orthodox group, Reform Jews in Greenville began to organize. By 1911, five Jewish families were meeting together in each other’s homes. In 1917, they formally established Children of Israel. Lee Rothschild was the congregation’s first president. Hyman Endel was among the founders, and Isaac W. Jacobi, who managed Rothschild’s store, served as lay reader. In 1928, the group began building a temple on a lot on Buist Avenue donated by founding member, Manos Meyers. One year later, the congregation dedicated the Temple of Israel and held its first confirmation. About 25 families funded the project. The sanctuary accommodated 112 people, and a kitchen and Sunday school classrooms were located on the ground floor. Approximately two dozen children were enrolled in the school, which had been established in the early 1920s under the direction of Isaac Jacobi and was run by the women of the temple’s Sisterhood.

Around 1910, these recent immigrants began to worship together, often led by Harris Bloom. In 1912, this Orthodox congregation hired Charles Zaglin, a Lithuanian immigrant living in Wilmington, North Carolina, as a rabbi, shochet, and mohel. Zaglin moved to Greenville and, at the insistence of his wife, Evelyn Rose, built a mikvah. A few years later, Charles gave up the position of rabbi, although he continued to serve as the community’s mohel and shochet. Zaglin opened a store offering kosher and non-kosher meat. According to his grandson, there weren’t enough Jews in Greenville to support a kosher-only market. The Orthodox group later adopted the name Beth Israel, and met in various rented rooms in Greenville. They had various rabbis during the 1920s, including Don Hechter and Jacob Aronson. Beth Israel began building its synagogue in the late 1920s on the north side of the city, where many of Greenville’s nearly 200 Jews lived at the time. Charles Zaglin donated the lot on Townes Street, and construction of the first phase, a hall, was completed in 1930. The sanctuary, located on the upper level, was added a few years later.

Around the same time as the founding of the Orthodox group, Reform Jews in Greenville began to organize. By 1911, five Jewish families were meeting together in each other’s homes. In 1917, they formally established Children of Israel. Lee Rothschild was the congregation’s first president. Hyman Endel was among the founders, and Isaac W. Jacobi, who managed Rothschild’s store, served as lay reader. In 1928, the group began building a temple on a lot on Buist Avenue donated by founding member, Manos Meyers. One year later, the congregation dedicated the Temple of Israel and held its first confirmation. About 25 families funded the project. The sanctuary accommodated 112 people, and a kitchen and Sunday school classrooms were located on the ground floor. Approximately two dozen children were enrolled in the school, which had been established in the early 1920s under the direction of Isaac Jacobi and was run by the women of the temple’s Sisterhood.

Davis Battery Company

Davis Battery Company

Jewish Businesses in Greenville

Although Greenville’s Jewish community was divided by religious differences, they were united by business, as most of the members of both Beth Israel and Temple of Israel owned retail stores. In the 1930s, as many as 30 Jewish-owned stores were located on Main Street in downtown Greenville. While they opened their doors every Saturday, their busiest day for customers, they closed for the High Holy Days.

The years of the Great Depression, however, severely challenged small town merchants in Greenville. Morris Chaplin, a Polish immigrant, moved his family from Columbia to Greenville in the early 1930s after his business in the capital city failed. Once in Greenville, he opened a pawn shop and was known to help out Jews who were passing through town and down on their luck. Bloom’s Department Store had to scale back the size of its operation and move to a smaller building. Beginning in 1926, Nathan Fleishman of Anderson and his wife’s brother-in-law, Philip Klyne, partnered in Fleishman and Klyne, a dry goods business in Anderson that added stores in Greenville, and Hartwell, Georgia. The Depression forced them to close the Georgia store and split the other two between them, Nathan keeping Anderson and Philip Greenville. Charles Zaglin’s daughter, Freida, moved back to Greenville in 1937 with her husband Nathaniel Kaplan to help with the meat market when Zaglin fell ill. The Kaplans continued to run the store after Charles died, although at some point, stopped selling kosher meat. After that, some of the local Jews relied on a market in Charlotte, North Carolina.

Greenville’s Jews owned other types of businesses as well. Victor Davis, a Jew of Sephardic descent, immigrated to the United States in 1908 from the Isle of Rhode. Davis had brothers in Atlanta, Georgia, and other family members in Montgomery, Alabama, where he met his wife, Molly Kaufman, a Romanian immigrant. The newlyweds ended up in Michigan, perhaps following one of Molly’s brothers, but moved to Greenville in 1922 when another Kaufman brother, the city’s first junkyard and auto parts dealer, needed assistance. Victor opened his own store, Davis Auto Parts, four years later.

Through the first half of the 20th century, manufacturing in the Greenville region continued to grow. Northern businessmen were drawn to the area by its cheap and abundant supply of labor. In the late 1920s, Shepard Saltzman moved south from New York and opened his factory, the Piedmont Shirt Company, possibly the first Jewish-owned textile manufacturing plant in Greenville. In 1936, Harry Abrams, the son of Russian immigrants, moved his family from New York to Greenville. Hired by Saltzman to run his plant, he supervised 300 to 400 employees.

The 1930s

The Great Depression weakened Jewish institutions in Greenville. Sometime in the early 1930s, Temple of Israel became inactive. When Harry Abrams arrived in 1936, he worked to revitalize the congregation. In 1937, they were able to hire Maurice Mazure as their full-time rabbi. Apparently the match was a good one, since he served as Temple of Israel’s spiritual leader until the mid-1960s. Despite the Reform congregation’s brief dormancy, the Jewish community as a whole was quite active in the 1930s. A local chapter of AZA (Aleph Zadik Aleph) and a B’nai Brith Lodge were organized. In 1938, the Beth Israel Cemetery Association was founded by members of both congregations. Morris Zaglin, Charles’ brother, was the first chairman of the association, which owned the Beth Israel Cemetery, a three-acre parcel of land adjacent to Graceland Cemetery. A year later, the Greenville section of the National Council of Jewish Women was established, which remains active today. The Jewish population of Greenville grew from 183 in 1937 to 260 ten years later.

Although Greenville’s Jewish community was divided by religious differences, they were united by business, as most of the members of both Beth Israel and Temple of Israel owned retail stores. In the 1930s, as many as 30 Jewish-owned stores were located on Main Street in downtown Greenville. While they opened their doors every Saturday, their busiest day for customers, they closed for the High Holy Days.

The years of the Great Depression, however, severely challenged small town merchants in Greenville. Morris Chaplin, a Polish immigrant, moved his family from Columbia to Greenville in the early 1930s after his business in the capital city failed. Once in Greenville, he opened a pawn shop and was known to help out Jews who were passing through town and down on their luck. Bloom’s Department Store had to scale back the size of its operation and move to a smaller building. Beginning in 1926, Nathan Fleishman of Anderson and his wife’s brother-in-law, Philip Klyne, partnered in Fleishman and Klyne, a dry goods business in Anderson that added stores in Greenville, and Hartwell, Georgia. The Depression forced them to close the Georgia store and split the other two between them, Nathan keeping Anderson and Philip Greenville. Charles Zaglin’s daughter, Freida, moved back to Greenville in 1937 with her husband Nathaniel Kaplan to help with the meat market when Zaglin fell ill. The Kaplans continued to run the store after Charles died, although at some point, stopped selling kosher meat. After that, some of the local Jews relied on a market in Charlotte, North Carolina.

Greenville’s Jews owned other types of businesses as well. Victor Davis, a Jew of Sephardic descent, immigrated to the United States in 1908 from the Isle of Rhode. Davis had brothers in Atlanta, Georgia, and other family members in Montgomery, Alabama, where he met his wife, Molly Kaufman, a Romanian immigrant. The newlyweds ended up in Michigan, perhaps following one of Molly’s brothers, but moved to Greenville in 1922 when another Kaufman brother, the city’s first junkyard and auto parts dealer, needed assistance. Victor opened his own store, Davis Auto Parts, four years later.

Through the first half of the 20th century, manufacturing in the Greenville region continued to grow. Northern businessmen were drawn to the area by its cheap and abundant supply of labor. In the late 1920s, Shepard Saltzman moved south from New York and opened his factory, the Piedmont Shirt Company, possibly the first Jewish-owned textile manufacturing plant in Greenville. In 1936, Harry Abrams, the son of Russian immigrants, moved his family from New York to Greenville. Hired by Saltzman to run his plant, he supervised 300 to 400 employees.

The 1930s

The Great Depression weakened Jewish institutions in Greenville. Sometime in the early 1930s, Temple of Israel became inactive. When Harry Abrams arrived in 1936, he worked to revitalize the congregation. In 1937, they were able to hire Maurice Mazure as their full-time rabbi. Apparently the match was a good one, since he served as Temple of Israel’s spiritual leader until the mid-1960s. Despite the Reform congregation’s brief dormancy, the Jewish community as a whole was quite active in the 1930s. A local chapter of AZA (Aleph Zadik Aleph) and a B’nai Brith Lodge were organized. In 1938, the Beth Israel Cemetery Association was founded by members of both congregations. Morris Zaglin, Charles’ brother, was the first chairman of the association, which owned the Beth Israel Cemetery, a three-acre parcel of land adjacent to Graceland Cemetery. A year later, the Greenville section of the National Council of Jewish Women was established, which remains active today. The Jewish population of Greenville grew from 183 in 1937 to 260 ten years later.

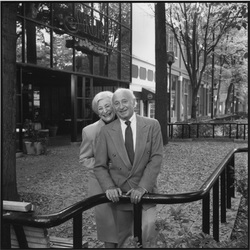

Max & Trude Heller. Photo by Bill Aron.

Max & Trude Heller. Photo by Bill Aron.

Max Heller

In the summer of 1938, Greenville gave sanctuary to a refugee from Nazi terror who, 33 years later, would become the city’s mayor. Nineteen-year-old Max Heller had met a Greenville girl named Mary Mills the year before, while she was visiting Vienna. When the Germans occupied Austria, Max wrote to ask for her help. Mary approached Shep Saltzman who provided affidavits not only for Max and his sister, but helped the Hellers’ parents and other members of the family immigrate to the United States as well. Max Heller went to work as a shipping clerk at Saltzman’s Piedmont Shirt Company and rose in the ranks to become plant manager. He married Trude Shönthal, a fellow Austrian he had met at a summer resort in 1937. Trude and her parents, after a harrowing escape from Europe, made it safely to New York in 1940 with the help of a distant cousin. In 1948, Max established his own factory, the Maxon Shirt Company, and 14 years later sold the plant in order to devote his time and energy to the public sector. Max, a strong proponent of providing housing for the poor, was instrumental in creating the Greenville Housing Foundation. In 1969, he was elected to Greenville’s City Council, serving until 1971, when he was elected mayor. A Democrat, Max drew a large number of voters to the polls for the primary and received significant bipartisan backing in the regular election. He supported integration and presided over the revitalization of downtown Greenville.

In the summer of 1938, Greenville gave sanctuary to a refugee from Nazi terror who, 33 years later, would become the city’s mayor. Nineteen-year-old Max Heller had met a Greenville girl named Mary Mills the year before, while she was visiting Vienna. When the Germans occupied Austria, Max wrote to ask for her help. Mary approached Shep Saltzman who provided affidavits not only for Max and his sister, but helped the Hellers’ parents and other members of the family immigrate to the United States as well. Max Heller went to work as a shipping clerk at Saltzman’s Piedmont Shirt Company and rose in the ranks to become plant manager. He married Trude Shönthal, a fellow Austrian he had met at a summer resort in 1937. Trude and her parents, after a harrowing escape from Europe, made it safely to New York in 1940 with the help of a distant cousin. In 1948, Max established his own factory, the Maxon Shirt Company, and 14 years later sold the plant in order to devote his time and energy to the public sector. Max, a strong proponent of providing housing for the poor, was instrumental in creating the Greenville Housing Foundation. In 1969, he was elected to Greenville’s City Council, serving until 1971, when he was elected mayor. A Democrat, Max drew a large number of voters to the polls for the primary and received significant bipartisan backing in the regular election. He supported integration and presided over the revitalization of downtown Greenville.

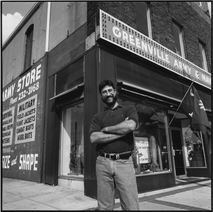

Jeff Zaglin in front of the Greenville Army & Navy store.

Jeff Zaglin in front of the Greenville Army & Navy store. Photo by Bill Aron

World War II and After

Greenville’s economic resurgence during World War II had been due, in part, to the establishment in 1942 of the Greenville Army Air Base on the outskirts of the city. In the decades after the war, city and regional leaders courted additional industries, from both the textile and non-textile sectors, to promote economic growth, successfully transforming the upcountry into a leading industrial area. Between 1947 and 1960, the Jewish population more than doubled to approximately 600, a number that remained constant over the next 25 years.

In the second half of the 20th century, Jews continued to own businesses and operate clothing stores, specialty shops, and factories, with a few keeping family-owned enterprises running into the next generation. After being discharged from the military at the end of World War II, Alex, Louis, and Jack Davis joined their father Victor in his auto parts store. The brothers ran the business together for nearly four decades. Alex’s son followed his father and uncles into the trade and wound up working for the company that purchased Davis Auto Parts in the mid-1990s. In 1988, Jeff Zaglin, Charles’s grandson, bought his father’s Army-Navy surplus store, which Harry had opened shortly after the war at the suggestion of his brother, Jack, who had gone into the same business in Atlanta. The Zaglins’ store, with “a little bit of everything,” remains a landmark in downtown Greenville today.

The number of Jewish professionals increased dramatically in the post-World War II era. In 1947, Jack Bloom, community historian, became the first of many Jewish attorneys to practice law in Greenville. Doctors E. Arthur Dreskin and Bruce Schlein were prominent pathologists hired by the local hospitals to manage their laboratories. Jeanet Dreskin, who moved to the city in 1950 with her husband, Arthur, was an artist specializing in medical illustrations. She headed Greenville County Museum’s art school from 1968–71, where she also taught classes for a number of years.

Greenville’s economic resurgence during World War II had been due, in part, to the establishment in 1942 of the Greenville Army Air Base on the outskirts of the city. In the decades after the war, city and regional leaders courted additional industries, from both the textile and non-textile sectors, to promote economic growth, successfully transforming the upcountry into a leading industrial area. Between 1947 and 1960, the Jewish population more than doubled to approximately 600, a number that remained constant over the next 25 years.

In the second half of the 20th century, Jews continued to own businesses and operate clothing stores, specialty shops, and factories, with a few keeping family-owned enterprises running into the next generation. After being discharged from the military at the end of World War II, Alex, Louis, and Jack Davis joined their father Victor in his auto parts store. The brothers ran the business together for nearly four decades. Alex’s son followed his father and uncles into the trade and wound up working for the company that purchased Davis Auto Parts in the mid-1990s. In 1988, Jeff Zaglin, Charles’s grandson, bought his father’s Army-Navy surplus store, which Harry had opened shortly after the war at the suggestion of his brother, Jack, who had gone into the same business in Atlanta. The Zaglins’ store, with “a little bit of everything,” remains a landmark in downtown Greenville today.

The number of Jewish professionals increased dramatically in the post-World War II era. In 1947, Jack Bloom, community historian, became the first of many Jewish attorneys to practice law in Greenville. Doctors E. Arthur Dreskin and Bruce Schlein were prominent pathologists hired by the local hospitals to manage their laboratories. Jeanet Dreskin, who moved to the city in 1950 with her husband, Arthur, was an artist specializing in medical illustrations. She headed Greenville County Museum’s art school from 1968–71, where she also taught classes for a number of years.

Beth Israel today

Beth Israel today

Growing Congregations

In 1957, Beth Israel’s growing congregation, which had transitioned from Orthodox to Conservative practices in the late 1940s, purchased land on Summit Drive for a new synagogue. The facility, built in stages over a number of years, included a sanctuary, chapel, social hall, kitchen, classrooms, offices, and a meeting room. Beth Israel has been transformed by Greenville’s recent growth. By 1998, 75% of Beth Israel’s 135 member families had arrived in Greenville over the previous 15 years.

Temple of Israel dedicated a newly renovated sanctuary in its original building on Buist Avenue and, two years later, broke ground for a new education wing. The six-classroom school was attached to the social hall. However, by 1989, the congregation found it necessary to move to a new location to accommodate its growing membership. In 1977, the temple had fewer than 100 members; by 1998, this number had doubled. The new property on Spring Forest Drive included classrooms, meeting rooms, and offices, in addition to the sanctuary. When the High Holidays arrived in 1990, the building was nearly complete, but still lacked lighting. A construction worker taped a Star of David to a work light and strung it high over the heads of the congregants for the first holiday service.

The relationship between the Conservative and Reform congregations has been congenial and mutually supportive. In the early 1980s, the two shuls considered merging. Yarmulkes and music were sticking points, however, and the idea was abandoned. A few years later, in a gesture of solidarity, the Beth Israel Cemetery Association, made up of people from both congregations, agreed to set aside a section in the cemetery for the burial of non-Jewish family members.

In 1957, Beth Israel’s growing congregation, which had transitioned from Orthodox to Conservative practices in the late 1940s, purchased land on Summit Drive for a new synagogue. The facility, built in stages over a number of years, included a sanctuary, chapel, social hall, kitchen, classrooms, offices, and a meeting room. Beth Israel has been transformed by Greenville’s recent growth. By 1998, 75% of Beth Israel’s 135 member families had arrived in Greenville over the previous 15 years.

Temple of Israel dedicated a newly renovated sanctuary in its original building on Buist Avenue and, two years later, broke ground for a new education wing. The six-classroom school was attached to the social hall. However, by 1989, the congregation found it necessary to move to a new location to accommodate its growing membership. In 1977, the temple had fewer than 100 members; by 1998, this number had doubled. The new property on Spring Forest Drive included classrooms, meeting rooms, and offices, in addition to the sanctuary. When the High Holidays arrived in 1990, the building was nearly complete, but still lacked lighting. A construction worker taped a Star of David to a work light and strung it high over the heads of the congregants for the first holiday service.

The relationship between the Conservative and Reform congregations has been congenial and mutually supportive. In the early 1980s, the two shuls considered merging. Yarmulkes and music were sticking points, however, and the idea was abandoned. A few years later, in a gesture of solidarity, the Beth Israel Cemetery Association, made up of people from both congregations, agreed to set aside a section in the cemetery for the burial of non-Jewish family members.

The Jewish Community in Greenville Today

Temple of Israel today

Temple of Israel today

Greenville’s Jewish population has grown dramatically since the mid-1980s as the city’s overall population has swelled with newcomers, drawn to a region with a strong economy. The majority of new residents have been from the Northeast. Jewish leaders estimate there may be as many as 700 Jewish families in the greater metropolitan area. In 2004, Temple of Israel began expanding its facilities. As of 2009, the Reform congregation numbered more than 200 families, with about 100 children enrolled in the religious school. Beth Israel, which is affiliated with the United Synagogues of Conservative Judaism, served about 140 families. With Greenville’s economic rise, its Jewish community seems poised to continue its impressive growth.